Evaluation of the Australia-Vietnam country strategy 2010–15

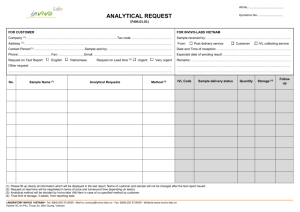

advertisement