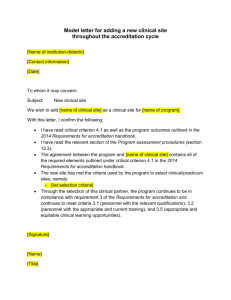

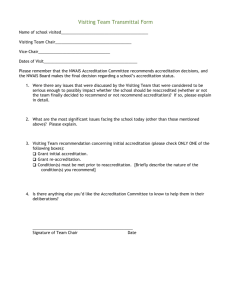

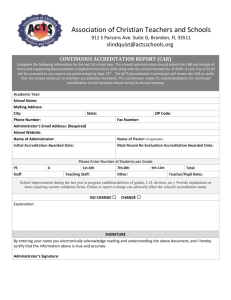

Review of third party accreditation of Designated

advertisement