Framework for a National Response to New Psychoactive Substances

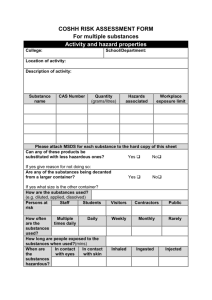

advertisement