Port 2 RD

advertisement

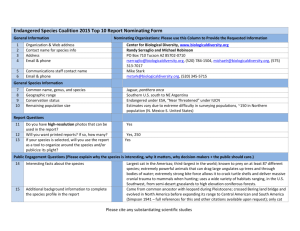

Stricker 1 Philip Stricker Professor Ryan CO 300 10 March 2010 Portfolio 2 RD Wildlife Corridors and their Effect on Jaguar Success Introduction: The study of wildlife corridors has throughout time been well studied and documented. There have been numerous books and articles written about wildlife corridors or just corridors and even courses are available to understand and practice wildlife corridor maintenance. Recently, in the last 40 years, there have been studies on the elusive Panthera onca and other top-level predators due because they were misunderstood and potentially extirpated. Most of the extirpation of toplevel predator was caused by habitat fragmentation and hunting from human populations. Estimates are the forest landscapes occupied by jaguars are becoming increasingly more fragmented and consequently leading to fewer resources available for species. Jaguars are an elusive species that despite their vast range are rarely seen or studied, but the increased fragmentation of the forest is also raising the number of conflicts between jaguars and humans. There has been more research done on the more social clan like predators of wolves and lions, but not much has been studied about the more solitary predators such as snow leopards, amor leopards, pumas or jaguars. Yet there hasn’t been much studied at all about the value and role that wildlife corridors play on the success for top-level predators, especially jaguars. In this paper, research done on jaguars and wildlife corridors has been compiled to prove the existence of wildlife corridors for jaguars need to be immediately preserved and enlarged to guarantee the future success of jaguars. Discussion: Habitat fragmentation leads to further fragmentation and species decline. Habitat fragmentation is the leading cause of species decline in the entire world. Little is known about whether habitat fragmentation is having the greatest effect on tropical climates species decline or is not due to limited accessibility to the region and also by the lack of research conducted in those regions. According to an article published by Philip M. Fearnside, states “that Brazil’s new Stricker 2 National Plan for Climate Change brings good news for goals for deforestation reduction in Brazilian Amazonia…but the plan does not contain objectives that need to be met” (Fearnside 177). Fearnside is saying that this new plan of Brazil’s is a good step, but that it will not actually help reduce habitat loss or habitat fragmentation. Brazil’s national animal is the Panthera onca, but with a policy such as the Plan for Climate Change allowing large escape holes for not reducing deforestation, it is no wonder that the animals near threatened status could become more threatened. Habitat fragmentation is never good for any species and especially for a predator species such as the Panthera onca that is a solitary cat which avoids human contact as much as possible. This invasion by people causes conflicts between people and wildlife; which people always win. Habitat fragmentation divides one larger landscape into two smaller landscapes, leading to more edge habitats. Most species avoid interactions with people by maintaining a buffer zone around edges to minimize people to wildlife conflicts. The increased creation of edges from agriculture and road production leads to further fragmentation (Prasad 201). Prasad’s research has shown that the impacts associated form road clearings and edges are, “increased tree mortality via microclimatic change, mechanical damage and high infestation rates by pathogens” (Prasad 201). This decrease in habitat availability by edge effects only leads to decrease habitat available to species and to increase need and use of corridors to travel. Prasad also points out from his study that increased edge zones leads to more exotic or invasive plants establishments and that these plant species can have a detrimental effect on the inhabitants and the forest system (Prasad 202). These findings by Prasad and Brazil’s National Plan for Climate Change clearly point out that habitat is becoming increasingly fragmented and the need to protect is ever more present. Species already forced to smaller spaces compete more with other species and own species for the reduced resources available, shown by numerous studies done; consequently not everyone can get the required resources and either move to areas with more resources, adapt to acquire an alternative source, or perish. Since people tend to prevent the enlargement of habitats the best alternative would be establishing corridors connecting isolated animals with larger areas with additional feeding and cover space. Prasad proposes the amount and number of roads and exotic plant invasion be minimized as much as possible and maybe even eliminated for the preservation and protection of endangered forest ecosystems (Prasad 205). Fearnside’s proposal for reduced deforestation would be policy change on the part for the Plan for Climate Change Stricker 3 such that the consequences for increased deforestation are dramatically increased and for possible escapes for deforestation by eliminated. In order to be successful and reproductive to continue the species, jaguars need to cover vast regions of land from South America to northern Mexico. Jaguars are similar in ways to their feline cousin the tiger, puma and leopard because they are solitary animals which prefer large regions of habitation that are away from other jaguars. A study done by Peter G. Crawshaw Jr. on the movements of jaguars showed that on average female cats range at least 25-38 km2 and males have a range twice the number (Schaller 161). Also found was for a specific area there would be found 1 cat per 25 sq km. Female jaguars range’s overlap, while male ranges overlap those of the females (Schaller 164). The overlapping of the males and females emphasizes the need for genetic diversity and species richness via the increased amount of females available and the overlapping to the species. Since the jaguar breed year round, the need to overlap ranges or but next to adjacent ranges makes breeding more successful due to the densities tropical forests (Defenders). Juvenile males, like relatives in Puma, Tigris, and Leopard, when they no longer need parental care from their mother are removed by the adult existing male. This means the juvenile male or female must search out an alternative range for success with members of the opposite sex to mate with. Consequently the need for habitat connection is a necessity for juvenile cats and roaming cats that haven’t established a permanent range. This movement of juveniles to free range is a means of immigration that adds more genetic diversity to different region, and preventing in-breeding and mutations. More recent studies done by Alan R. Rabinowitz has shown that depending on the region of North or South America and the environmental conditions within, the home range of jaguars can vary (Rabinowitz 150). Jaguars found in southern Arizona and New Mexico have the capability to interbreed and produce viable offspring with jaguar found in Argentina (Rabinowitz 158). This means that jaguars have the potential to travel very great distances and still be able to reproduce successfully. It has also been seen that male jaguars tend to travel very great distances and maintain large territorial ranges for food and prospective mates. His study explains that males will stay within a smaller range of about 2.5 km2 for several days to several weeks, before shifting in a single move at night to another part of his range. This is in part of the abundance of prey and possibly to the adjacent jaguars to his range maintaining a close proximity to other parts of his range. These cats tend to have a nocturnal lifestyle, attributed to the prey on which they Stricker 4 consume also live a nocturnal lifestyle (Rabinowitz 150). Jaguars can unlike pumas live in relative high densities because of the opportunistic lifestyle they live. With living in close proximity with each other jaguars that have either died or been killed have their home range quickly occupied by neighboring males or by immigrating males by connections to other areas (Rabinowitz 152). According to Rabinowitz and proven in his data, “the behavioural and ecological plasticity exhibited by the movements, activity patterns and feeding patterns observed… displays the adaptive capability of jaguars.” But he warns the adaptability of the jaguar can only go so far with lose of connects to maintain species richness. Jaguars are key predator species that are needed to keep prey population densities in check so as not to push ecosystem balance out of swing. As seen from the extermination of the wolves from Yellowstone National Park, top predators greatly influence ecosystems. Top predators are species that have no predators of their own and are at the top of the food chain. After the last wolf was removed from the park in the 1920’s the elk population rebounded and began overgrazing crucial habitat such as aspen, willow, cottonwood near streams that prevent erosion (Chadwick 42). The lack of trees decreased the nest space available for birds. Stream vegetation was absent so streams became wider from erosion, so fish and aquatic species had no place to hide or feed and declined consequently. Coyotes, the next in line predator, did not eat as much elk and instead consumed ground squirrels, voles, and other smaller prey. This resulted in reduced prey amount for raptors, hawks, owls, badgers, and foxes. All this was due to the removal of the key predator from the area. When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reintroduced the gray wolf back into Yellowstone in 1995 drastic changes occurred with the ecosystem (Chadwick 38). First of all the elk population was nearly reduced in halve (Chadwick 40). The reduction in elk then allowed the vegetation to grow and provide cover and food for numerous species. What was learned was that the extent to which top predators play on the balance of the surrounding ecosystem was much more important than previously thought of. The wolves of Yellowstone, Idaho and Montana are examples of the important role that top-level predators do for the sustainability of balancing ecosystems. Like wolves, jaguars are also top-level predators, they consume just about anything they can catch with nothing preying on them. There have been no studies done on the role the jaguar assumes in regulating prey densities. The reason for this is observations done in the forests are extremely difficult and the abundance of available food for the jaguars is too immense. Also the ability to set up an Stricker 5 experiment to remove the all the jaguars from the area of study to understand its role would be very hard to do. But from studies done on wolves, cougars, and tigers it can be assessed that jaguars do play a significant role in ecosystem balance. The stability of their population sizes and their ability to move throughout habitats as the top-level predator is crucial for the maintenance of stable ecosystems similar to that of wolves discussed earlier. Conclusion: More research needs to be done to fully understand the relationship that occurs between wildlife corridors and jaguars. One way would be to find out from tracking individual cats that have no permanent home range how they go about moving? Whether they avoid other established home ranges? Do they use corridors? Is there a width requirement for the habitat? Is the near presence of humans/ civilization a deterrent or a factor in deciding where to go? What all factors are needed for the corridor; tree heights, streams, rivers, length? Also, what is the frequency to which corridors are used for movement? It is understood amongst many that top-level predators play a crucial role in ecosystem health and so is the maintenance of wildlife corridors for species richness. It is now necessary for the research of Panthera onca and wildlife corridors to become more prevalent so that another repeat of wolf extinction does not transpire.