Compilation of case studies

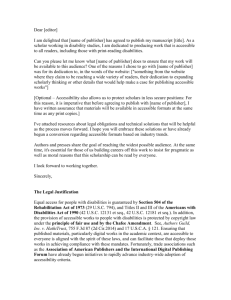

advertisement