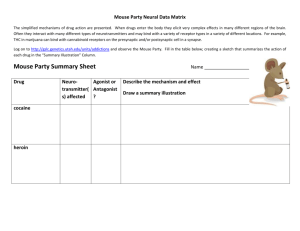

Medical Marijuana Paper

advertisement

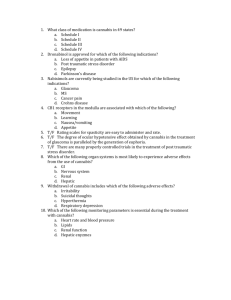

Running head: THROUGH THE HAZE Through the Haze: Medicinal Cannabis Properties for Chemotherapy Patients Phi David Hoang, Helen Jang, John Rhee, Noel Kwok, & Tara Hooley San Francisco State University DFM 655 - Nutrition Education and Communication THROUGH THE HAZE 1 Introduction Complementary alternative medicine is defined as using non-mainstream health systems as opposed to conventional medicine ("Complementary, alternative, or," 2014). One ancient form of plant medicine is the cannabis plant, otherwise known as marijuana. Modern use of medical cannabis is generally used to provide pain relief and stimulate appetite for patients with cancer and immune disorders. Over the past seventy years, there has been legal conflicts over the use of medical marijuana with the passing of both the Marijuana Tax Law of 1937 and the Controlled Substance Act of 1970. Currently, twenty-three states have legalized medical marijuana use. Despite this, cannabis is still listed as a Schedule I substance, a substance not accepted for medicinal use and has the potential of abuse ("Regulatory Information," 2009). However, each decade there have been concerted efforts to repeal these acts. Dietitians are not encouraged to advise marijuana usage; however, with further research being carried out to ascertain effectiveness, perspectives on how we implement medical marijuana could change the future of medical-care. History and Description Earliest findings of cannabis originate approximately five thousand years ago in China. It was later incorporated into medical practice into most of the Western world. In America, there was a social stigma suggesting cannabis usage with alcohol consumption were closely related; therefore, congress passed the Marijuana act of 1937 stating all cannabis would be illegal, and sales of medical cannabis from physicians would be taxed. This caused a decline in the use of medical marijuana. The focus of medical marijuana is on the phytocannabinoid constituent, trans-delta-9tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) which causes popular benefits such as: reduction of neuropathic THROUGH THE HAZE 2 pain, nausea and vomiting, increased ocular blood flow which helps with glaucoma, epileptic episodes, improvement of muscle stiffness, suppression of autoimmune disease, and prevention of cancerous tumors (Grant, Atkinson, Gouaux & Wilsey, 2012). Usage of medical marijuana includes ingestion through pills, eating, smoking, sublingually, or inhalation through vapors. Historical Usage The first recorded medicinal use of cannabis was by Emperor Shen-nung of China, in around 2,727 B.C. (Mikuriya, 1969). Dosage for medicinal usage at the time was not recorded. However, there are records of the methods of usage indicating cannabis extracts were applied topically, or consumed with foods (Mikuriya, 1969). Another popular of usage recorded later in the nineteenth century was smoking. Cannabis became widely accepted by western medical practitioners for treatment of burns however; its usage declined around the turn of the twentieth century, as other method medicines were proven to be more effective. Until the 1930’s, cannabis was readily available as an over-the-counter prescription as cannabis extract medicine (Mikuriya, 1969). Afterward, cannabis gradually lost its reputation for medicinal use and was criminalized by many countries. Modern Usage Nowadays, medical marijuana is available in pill form such as Dronabinol and Nabilone in which THC works as an antiemetic (Le Foll, 2010). Both are FDA approved medications used to treat nausea and vomiting and stimulate appetite for cancer patients receiving chemotherapy (Zanni, 2013). Nabilone is typically administered a starting dose of 1 to 2 mg twice a day and effects can last from eight to twelve hours. The first dosage is usually given one to three hours prior to chemotherapy, and then subsequent doses every two to four hours after treatment. Dronabinol is usually presented in the form of a capsule containing 2.5mg, 5mg or 10mg of THROUGH THE HAZE 3 THC. The maximum recommended dosage to alleviate nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy is 5 to 15 mg/m2, without exceeding four to six doses per day (Amar, 2006). The initial dose is 5 mg/m2 per day (Marinol, 2004). However, the dose may be increased by 2.5mg/m2 increments to a maximum of 15 mg/m2 depending on patient’s reaction to the dose and its side effects. Regardless, the drug can have an effect on the patient up to four to six hours long. Effectiveness and Efficacy The most unpleasant aspect of chemotherapy is induced nausea and vomiting, affecting 70-80% of cancer patients (Ware, Daeninck, & Maida, 2008). The interaction between Nabilone and cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), a ligand, produces an antiemetic effect. Usually, neurotransmitters are released from the axon terminal of presynaptic neuron to the postsynaptic neuron. Exogenous cannabinoids, THC, and endocannabinoids like anandamide, created in the postsynaptic region, have an affinity for CB1, located in the presynaptic neuron. This creates a “reverse signaling process”, reuptake of cannabinoids back to the presynaptic neuron (Kovacs et al., 2012). This activation of CB1 receptors by cannabinoids produces antiemetic effects by decreasing neurotransmitters responsible for nausea and vomiting (Croxford, 2003). A study with severe chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) patients taking Nabilone showed 77% had reduction in nausea and vomiting with more than half of the patients also reporting “excellent condition” for resolution of CINV, and half had an increased appetite (Ware, Daeninck, & Maida, 2008). Other crossover studies have shown patients preferred cannabinoids as an antiemetic for future chemotherapy treatments over conventional medications (Machado, Stéfano, De Cássia Haiek, Rosa Oliveira, & Da Silveira, 2008). Nutrition Facts Medical marijuana is rarely consumed for its nutritional content; however, the leaves of THROUGH THE HAZE 4 the plant actually contain a complex phytochemistry of over 480 compounds and are a source of fiber in the form of lignans (Flores-Sanchez, & Verpoorte, 2008). Cannabis does not have any psychoactive effect until it is heated, so can be consumed safely without altering the conscious state (Russo, et al., 2008). Several primary metabolites have been identified, including amino and fatty acids (Wang, Tang, Chen, & Yang, 2009). Analysis of the leaves indicates variations in biosynthesis of these metabolites depending on growth conditions of the plant, age, and tissue type (Flores-Sanchez & Verpoorte, 2008). Secondary metabolites including flavonoids are also present in cannabis leaves. Flavonoids have no primary function for the plant, but provide high levels of antioxidants, beneficial for human health (Kumar, & Pandey 2013). An increasingly popular way of utilizing these nutritional benefits is through consumption of hemp, derived from the same plant as cannabis. The main difference between the two is marijuana’s higher content of THC. Hemp oil, often referred to as cannabis oil, is sold and consumed legally when stripped of its THC. Cannabis oil is considered one of the most nutritionally dense vegetable oils available, due to a high content of vitamin E, B vitamins, and all nine essential amino acids (Vahanvaty, 2009). Cannabis oil also contains high levels of fatty acids, the most abundant being polyunsaturated omega-6 linoleic (55%), omega-3 α-linolenic (16%), and omega-9 oleic (11%) (Montserrat-de la Paz, 2014). Hemp is also readily available as nutrient dense seeds with around 11g protein and 2g α-linolenic acids per two tablespoons, making hemp an ideal choice for chemotherapy patients with cachexia (Vahanvaty, 2009). Drug Interactions and Side Effects Inhalation of cannabis can lead to rapid and predictable signs and symptoms. Ingesting cannabis orally can produce slower, less predictable effects (Grant et al., 2012). Euphoria, relaxation, and sleepiness are common effects of using cannabis. As dosage increases, so do the THROUGH THE HAZE 5 effects, including adverse effects. At low dosage, common side effects can include dry mouth, momentary memory loss, increased heart rate, perception and motor skills impairment, and blood-shot eyes (Marijuana intoxication, 2014). At higher dosage or with new users, more serious side effects such as paranoia, panic, or even severe psychosis can occur. It is in the best interest of the patient to be closely monitored for these side effects when taking these drugs. The dose-dependent characteristic of cannabis can also cause short-term withdrawal syndrome. A low dose of THC, 10 mg, will have withdrawal syndrome that usually lasts 48 to 72 hours. At higher doses, 20-30 mg, abstinence syndrome can develop causing irritability, anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, and poor appetite (Grant et al., 2012). Discussion The growing popularity of marijuana usage in modern society has resulted in numerous research studies for its medical application. Studies continue to show that marijuana’s medicinal properties can have a legitimate place in modern healthcare. However, its health and psychological effects remains the subject of much debate. Due to concerns of negative side effects and opinions on the legality of marijuana, it is difficult to implement a potentially useful drug into a patient care plan without moral and legal conflict. Recommendations for using medical marijuana as an alternative medicine, should only be issued by legally qualified professionals. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics currently has no positional stance on the usage of medical marijuana. In states where it is not decriminalized, dietitians should not advise marijuana usage to patients. However, dietitians are not legally required to report patients who are using marijuana and can prescribe nutritional therapy around their usage without any legal repercussions (Academy Position Papers, 2014). For dietitians, their primary focus is on helping chemotherapy patients or other patients receiving intensive THROUGH THE HAZE 6 medical treatments, to maintain their body weight and prevent the vicious cycle of malnutrition. Evidence suggests that by alleviating nausea for these patients, marijuana does help to improve health status. Conclusion The use of medical marijuana across America is proving to be an effective way to help alleviate the side effects of chemotherapy by reducing nausea and vomiting and also stimulating appetite in patients. Medicinal use of marijuana is seen in countries like the Netherlands, Spain, and Uruguay as well as other countries where marijuana is both legal and decriminalized. The majority of other countries such as Australia and about all the countries in Asia however, remain skeptical and are yet to decriminalize marijuana or utilize it for medicinal use. The vast medical benefits of marijuana should not be disregarded due to stigmatic and rash legislation. As perspectives continue to change, marijuana’s slow integration into the modern medical system can only be legitimized through further research and government legislation. Prescription of marijuana should not be limited due to poor understanding or bad legislation. Both risks and benefits of medical marijuana should be assessed adequately in order to maintain an unprejudiced stance. Patient health should be the priority; therefore, medical marijuana need to be further researched with due diligence. THROUGH THE HAZE 7 References Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. (2014) Academy Position Papers. Retrieved from http://www.eatright.org/About/Content.aspx?id=6442460576 Advanced Holistic Health. (n.d.). 10,000-year History of Marijuana use in the World. Retrieved from http://www.advancedholistichealth.org/history.html Amar, M. (2006). Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, (105), 1-25. A Train Education. (n.d.). Retrieved October 26, 2014, from https://www.atrainceu.com/coursemodule/1864531-105_marijuana-for-medical-use-module-06 Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What’s in a name?. (2014, July 15). Retrieved from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam Croxford, J. (2003). Therapeutic potential of cannabinoids in cns disease. CNS Drugs, 17(3), 179-202. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12617697 Flores-Sanchez, I. , & Verpoorte, R. (2008). Secondary metabolism in cannabis. Phytochemistry Reviews, 7(3), 615-639. Flores-Sanchez, I. , & Verpoorte, R. (2008). Pks activities and biosynthesis of cannabinoids and flavonoids in cannabis sativa l. plants. Plant and Cell Physiology, 49(12), 1767-1782. Grant, I., Atkinson, J. H., Gouaux, B., & Wilsey, B. (2012). Medical marijuana: Clearing away the smoke. Open Neurology Journal, 6, 18-25. doi: 10.2174/1874205X01206010018 Kovacs, F. E., Knop, T., Urbanski, M. J., Freiman, I., Freiman, T. M., Reuerstein, T. J., Zentner, J., & Szabo, B. (2012). Exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids suppress inhibitory neurotransmission in the human neocortex. Neuropsychopharmacology, (37), 1104-1114. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.262 Kumar, S. and Pandey, A.K. (2013). Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview, The Scientific World Journal, vol. 2013. Le Foll, B. (2010). Dronabinol. Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology, 425-425. Machado Rocha, F. , Stéfano, S. , De Cássia Haiek, R. , Rosa Oliveira, L. , & Da Silveira, D. (2008). Therapeutic use of cannabis sativa on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting among cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer Care, 17(5), 431-443. Marijuana intoxication: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (2014). Retrieved October 27, 2014, from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000952.htm THROUGH THE HAZE 8 Marinol (Dronabinol) Capsules. (2004, September 1). Retrieved October 28, 2014, from http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dockets/05n0479/05N-0479-emc0004-04.pdf Mikuriya, T. (1969, Jan 10). Marijuana in Medicine. California Medicine, 110(1): 34-40. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1503422/pdf/ califmed00019-0036.pdf National Commission of Marijuana and Drug Abuse (2009, March 29). History of the Medical Use of Marijuana. Retrieved from https://www.erowid.org/plants/cannabis/cannabis _medical_info3.shtml Regulatory information. (2009, Jun 11). Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/ucm148726.htm Russo, E. , Jiang, H. , Li, X. , Sutton, A. , Carboni, A. , Bianco, F., Mandolino, G., Potter, D.J., Zhao, Y., Bera, S., Zhang, Y., Lu, E., Ferguson, E.K., Hueber, F., Zhao, L., Liu, C.,Wang, Y., Li, C. (2008). Phytochemical and genetic analyses of ancient cannabis from central asia. Journal of Experimental Botany, 59(15), 4171-4182. Sanchez, A.J. and Garcia-Merino, A. (2012). Neuroprotective Agents Cannabinoids, Clinical Immunology, 142(1), 57-67. Tramer, M. R., Carroll, D., Campbell, F. A., Reynolds, D. J. M., Moore, A., & McQuay, H. J. (2001). Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. British Medical Journal, 323(16), 1-8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7303.16 Vahanvaty, U.S. (2009). Hemp Seed and Hemp Milk: The New Super Foods?. Infant, Child & Adolescent Nutrition, 1(4), 232-234.doi:10.1177/1941406409342121. Wang, X., Tang, C., Chen, L. and Yang, X. (2009). Characterization and antioxidant properties of hemp protein hydrolysates obtained with neutrase. Food Technology and Biotechnology, 47(4), 428-434. Ware, M., Daeninck, P., & Maida, V. (2008). A review of nabilone in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Retrieved October 27, 2014, from PMC. Zanni, G. R. (2013). Medical Marijuana. Pharmacy Times, 79(3), 54-58.