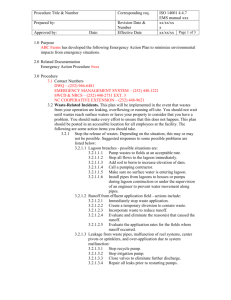

Little Llangothlin Nature Reserve Ramsar site Ecological Character

advertisement