The Odyssey - Cloudfront.net

advertisement

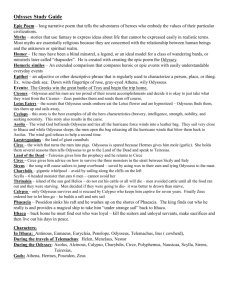

The Odyssey Study Guide THE ODYSSEY Homer Translated by Robert Fagles The Odyssey is a story of one man’s struggle to return home after an age of war. Both mortals and gods play their parts, creating a tale of many fantastic stories and adventures. Like its predecessor, The Iliad, it deals with human faults and their consequences. Why you’re reading this book: It is one of the primary foundations of Western literature; the epic form it uses serves as a model for many later works. Its action-packed narrative and its focus on one character’s individual struggle make it a precursor to the novel. Its central theme – one man’s struggle to fulfill his duty – is still relevant today. The Odyssey is a valuable historical text and an essential key to understanding ancient Greek culture: it provides an understanding of Greek mythology, which shaped the morals and ethics of the Greeks and determined how they viewed the world; it contains historical facts about actual kings, warriors, families, and events. Your teachers are looking for: The relationship between the gods and the mortals The system of justice in Homer’s world Odysseus and his education through his travels Homer’s notion of heroism The characteristics and style of the epic genre As you read The Odyssey, it will be helpful to keep the basic beliefs of Greek mythology in mind. Unlike in JudeoChristian mythology, the Greek gods share the same weaknesses and temptations as mortals. In the Greek world, human affairs mirror those of the gods, human events have cosmic significance. Important Greek Terms: Hubris: Excessive pride Xenia: Greek cultural custom of hospitality (generosity and courtesy to those far from home). Arête: Greek word meaning “possessing an excellent ability at something” or moral virtue of men and women. Nemesis: Source of harm or ruin; unbeatable foe. Kleos: Glory Nostos: Journey/Homecoming and Memory of lost home (nostalgia/yearning). Dolos: Trickery or deception (weaving) Penthos: Grief/Suffering Basic Chronology of the Homeric Epics (all dates BC) BRONZE AGE (3000-1100) c. 1800-1250 Troy VI c. 1500-1120 Mycenaean Civilization c. 1250 possible date of the historical fall of Troy VI 1183 traditional date of the fall of Troy DARK AGES (1100-800) c. 1100-750 Stories of the fall of Troy passed down in oral form c. 1100 Doric Invasion of Greece c. 1050-950 Greek colonization of Asia Minor (western coast of Turkey) c. 900 Beginning of the rise of the polis (city-state) ARCHAIC PERIOD (800-500) c. 800-700 Rise of the aristocracies 776 Olympic Games established c. 750 Greek colonization of Southern Italy and Sicily begins c. 750 Introduction of a new alphabet; writing gradually introduced c. 720 Homer, Iliad c. 700 Hesiod, Theogony and Works and Days c. 680 Homer, Odyssey; Archilochus (lyric poet) c. 650 Greek colonization around the Black Sea begins c. 600 Sappho (lyric poet); Thales (philosopher) 594-593 Archonship of Solon in Athens 545-510 Tyranny of the Peisistratids in Athens c. 540 Singing of Homeric poems begins at Panathenaic festival 533 Thespis wins first tragedy competition at Athens 508 Cleisthenes reforms the Athenian Constitution CLASSICAL PERIOD (500-323) 490-479 Persian War 458 Aeschylus, Oresteia 461-429 Pericles dominant in Athenian politics; the "Periclean Age" c. 450-420 Herodotus composes his Histories about the Persian War. 447 Parthenon begun in Athens 431-404 Peloponnesian War (Athens and allies vs. Sparta and allies) c. 428 Sophocles, Oedipus the King c. 424-400 Thucydides composes his History of the Peloponnesian War 404 Athens loses Peloponnesian War to Sparta 399 Trial and death of Socrates 2 Key to Map of Possible Route of Odysseus Graphic: Tim Severin, The Ulysses Voyage: sea search for the Odyssey (London 1987). Text: adapted from Erich Lessing, The Voyages of Ulysses (Vienna 1965) and other sources 1. Troy: After 10 years of siege, the Greek forces capture and destroy the city; then they sail for home with their spoils. Homer's version is told in Iliad. 2. Coast of Thrace: Odysseus and his men destroy and plunder Ismarus, city of the Cicones, but are eventually driven away with losses. 3. Lotus-eaters: Blown off course, Odysseus' fleet lands on shores of North Africa or the island of Jerba, possible locations for the drugged natives. 4. Cyclops: Near Naples are the caves of Mt. Posillipo and the Phlegraean Fields; another possible location for Cyclops is Sicily. 5. Aeolus: Ruler of the Winds, he lives on Stromboli, the Aeolian Island. His gift to Odysseus of a leather pouch, which controls the wild winds, allows the fleet to sail in sight of Ithica, when the crew causes disaster. 6. Laestrygonians: Cape Bonifacio is at the south coast of Corsica, where a race of giants destroy all of the fleet and men except for Odysseus' boat and crew. 7. Circe: This beautiful, sinister goddess lives on the island of Aeaea, now associated with Monte Circeo. With her magic, she enslaves men by turning them into animals. She tells Odysseus that he must enter the Halls of Hades before he can return home. 3 8. Entrance to the Underworld: Lake Avernus, near Salerno; but Tim Severin interprets the descriptions as resembling locations on the Greek coast. Here Odysseus speaks with the dead and consults the blind prophet Tiresias. 9. Sirens: Isole li Galli in the Gulf of Sorrento are known as the Islands of the Sirens, where Odysseus is tied to the mast of his ship so he can listen to their deadly songs. 10. Scylla & Charybdis: The Straits of Messina contain the narrows where Scylla, monster of the ocean caves, and Charybdis, the whirlpool, challenge passage. 11. Thrinacia: Sicily, island home of the sun-god, Hyperion. Odysseus' remaining crew and boat are destroyed as punishment for killing Hyperion's protected cattle. 12. Calypso: Odysseus is washed up on Calypso's island of Ogygia, present-day Malta. He stays with this tempting goddess 7 years before the Olympian gods relent and let him resume his journey home. 13. Phaecians: Their secluded island, Scheria, is present-day Corfu. These magical sailors escort Odysseus home, after he tells his story. 14. Ithaca: Island home to which Odysseus returns after 20 years away from his faithful wife, Penelope, and son, Telemachus. 15. Pylos: Home of King Nestor, with whom Telemachus consults. 16. Sparta: Land of King Menelaus, whose wife, Helen, is at the center of the conflict causing the 10-year war with Troy. 17. Mycenae: Land of Agamemnon, king of the Achaeans, brother of Menelaus. He was a major leader in the war against Troy. 18. Knossos: On present-day Crete, home of legendary King Minos whose vast constructions let to the legend of the Labyrinth. 4 Patterns in Greek Myths During your study of Greek Myths this summer you most likely became aware of aware of certain patterns and motifs. These motifs help us make sense out of the myths, and they are valuable tools for you to use in the future when analyzing literature. Be on the lookout for these patterns as we read The Odyssey. 1. HUBRIS Greek concept of “reaching beyond one’s grasp” excessive pride; arrogance whenever a character exhibits hubris in Greek myths, s/he is usually quickly punished or “brought down” good examples of HUBRIS as a theme/motif: Icarus – he flew too close to the sun, which melted his wings and he fell to his death Prometheus – gave humans fire, which he wasn’t supposed to do. He was punished for stealing the fire. King Midas – wanted to be ultra-rich, but his wish backfired on him Phaeton – wanted to drive his dad’s chariot, but wasn’t ready for the task Arachne – bragged that she could weave as well as Athena 2. THE HERO’S JOURNEY in Greek myth, as in other cultures’ myths and our current popular culture, the pattern of the Hero’s Journey emerges over and over again (see additional hand out on the Hero’s Journey if you need a refresher) good examples of the Hero’s Journey as a theme/motif: * Hercules myth * Jason and the Argonauts * Perseus * Theseus * Odysseus 3. CRIME and PUNISHMENT characters are often doing things that are against the rules, or which anger the gods/goddesses, for which they are usually swiftly punished this crime and punishment motif can often be very similar to the concept of HUBRIS; in a god’s opinion, trying to be more than human, extra-special, or god-like, can be grounds for punishment this motif is also closely related to revenge---Hera, Zeus, Poseidon and others are constantly seeking revenge on poor mortals for various wrongs, even though the ‘crime’ might seem very minor to us. good examples of the Crime/Punishment/Revenge motif: * The Odyssey * Prometheus * Sisyphus * Hercules 4. FATE/DESTINY/PROPHESY Greek myth is FULL of characters who hear a prophesy, don’t like what it says, and then try to do something to make the prophesy unable to come true. Of course, this never seems to work. good examples of the Fate/Destiny/Prophesy Motif: * Prophesy that one of Cronus’ kids would kill him * Prophesy that Oedipus would kill his dad and marry his mom * Prophesy that Achilles would be wounded in battle and die 5 5. GUEST/HOST RELATIONSHIP the relationship, the responsibility, between hosts and their guests was sacred hosts were expected to provide hospitality and protection for their guests, and hosts and guests exchanged gifts to harm a guest, or vice versa was a HUGE NO-NO! All manner of awful things could happen to you if you neglected your responsibility to be a good host or a good guest. good examples of the Guest/Host motif: (examples of what NOT to do…) * Paris stealing the wife of his host * Odysseus stealing the goats that belonged to the Cyclops (his ‘host’) * Procrustes – stretched out or cut off legs of his guests to fit the bed * the suitors staying at Odysseus’ house too long and eating all his food 6. SHOWING PROPER RESPECT TO THE GODS mortals were expected to respect the god/desses by praying to them, building temples and shrines to them, and offering sacrifices to them (usually by burning the parts of an animal that people don’t want to eat if a mortal did not show respect, s/he could expect to be punished Good examples of this motif: * Odysseus being punished by Poseidon for hurting his son and bragging * Pasiphae punished by Aphrodite after she said she didn’t believe in gods 7. RESPECT FOR THE DEAD it was very important for ancient Greeks to treat the bodies of the dead with respect and to have a proper funeral and certain rites performed. Without this, they believed the soul would be stranded on the wrong side of the River Styx in the Underworld Good examples of this motif: * the outrageous act of Achilles dragging the dead body of Hector around the city of Troy * Odysseus and his men not having a funeral for one of the sailors – couldn’t get into the Underworld 6 The Odyssey: An Overview for the Student (Note: The following literary terms and examples are adapted from http://www.leasttern.com/HighSchool/odyssey/Odyssey1.html.) TERMS AND CONVENTIONS Epic The Odyssey is an epic, a long narrative poem about the deeds of gods or heroes who embody the values of the culture of which they are they are a part. The oldest epics were transmitted orally and The Odyssey has traits (see the epithet) that suggest that it has roots in this tradition. Epic Hero The central hero of an epic, the epic hero has larger-than-life powers. Achilles fulfills this role in The Iliad; Odysseus in The Odyssey. Epic heroes are not perfect. Achilles is stubbornly proud over a long period of time; Odysseus has lapses in judgment. Nevertheless, epic heroes always seem to have an abundance of courage, a fighting spirit that endears them both to the reader (listener) and the gods. Epithets: Homer repeatedly describes many of his characters or objects in his story with the same phrase. This phrase is called an epithet. Epithets are common epic elements which allow the reader to easily identify the character or object. Epithets stress a quality of what they are describing. The same character often is given several different epithets. The epithet was used by oral poets to help them "catch their breath" whenever they mention a major figure or describe something familiar and recurring. The epithets were not used to illustrate a specific aspect of the figure at the moment he (she) is being spoken of, but were chosen to fit the meter of the line. Many translators, however, like to fit the epithet to an aspect of the character that is relevant to the moment. Examples of epithets used in The Odyssey are: "The great tactician" - This term creates the image of Odysseus as being intelligent, and probably comes his being the initiator of the idea for the "Trojan horse." "The clear eyed goddess" - This helps the reader imagine that Athena is alert, and wise - farseeing. Narrative drift Homer is constantly interrupting the narration to elaborate on an aspect of what he is talking about; if he mentions a gift of wine, he will explain not only the history of the gift but the history of the giver. He rarely introduces a character without alluding to that character's genealogy and often follows this with an aside in the form of a story that is told with the same vividness as the main story. The most celebrated of these asides is the story of how Odysseus received the scar that Eurycleia recognizes in Book 19. POETICS Meter: The Odyssey was written in a dactylic hexameter. Each line of the epic has 6 metrical feet, or small groups of sound. The first five feet are dactyls which are composed of a long sound and 2 short sounds. The last foot of each line is always a spondee which is made up of 2 long sounds. The Greek version of The Iliad follows these rules exactly, but only a few English translations have tried to follow it. English has stresses rather than long and short sounds. Fagles commented, "Once you get that Greek hexameter in your ear, it becomes the most gorgeous line of poetry ever conceived . . . .And the more it lodges, the more you realize there's nothing like it in English and you mustn't try to reproduce it." The Fagles translation employs a six beat line, but he varies this to achieve a "range in rhythm, pace, and tone." Formal Speech: In The Odyssey the characters tend to make speeches rather than have conversations. (An exception to this is some of the dialogue between the suitors and between the suitors and Telemachus in Book 20.) Many of these speeches can be long and at times formulaic, and some parts can be repeated word for word at another point in the poem. The most startling example occurs when Odysseus repeats Agamemnon's plea for Achilles to come back to fight for the Achaeans in The Iliad. 7 Imagery Many wonder how Homer could possibly have been blind. He visualizes everything from Athena's blazing eyes to the wind dark sea to Alcinous' palace: A radiance as strong as the moon came flooding through the high roofed halls of generous Alcinous. Walls plated in bronze, crowned with a circling frieze glazed as blue as lapis ran to left and right from outer gates to the deepest court recess and solid gold doors enclosed the palace. Up from the bronze threshold sliver doorposts rose with silver lintel above, and golden handles, too. And dogs of gold and silver were stationed on either side. Homer's imagery is vivid. He gives us extraordinary detail. Some of Homer's descriptions are clearly hyperbolic, but many of them gives us a sense of what the world of his time must have looked like. Even when it is hard to picture everything he describes - no one seems to have figured out how the axes Odysseus shoots the arrow through line up - we sense it is a failure of our imagination not his powers: First [Telemachus] planted the axes, digging a long trench, one for all and trued them all to a line then tamped the earth to bed them. Wonder took the revelers: his work so firm, precise though he'd never seen the axes ranged before. In addition to letting us see his world, Homer lets us hear it as well. Armor is "clashing in an ungoldly uproar"; At Athena's instigation "mad, hysterical laughter seemed to break from the jaws of strangers"; "the king let loose a howling through the town"; Eumaeus’ "snarling dogs" emit a "a shatter of barks." FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE Homer loves similes (a comparison between two seemingly unlike things using "like" or "as"). They can be found everywhere in The Odyssey. Homer often expands upon a simile, putting it into motion so to speak; and these expanded similes are called Homeric or epic similes. Weak as the doe that beds down her fawns in a mighty lion's den - her newborn sucklings then trails off to the mountain spurs and grassy bends to graze her fill, but back the lion comes to his own lair and the master deals both fawns a ghastly, bloody death, just what Odysseus will deal that mob - ghastly death. As a man will bury his glowing brand in black ashes, off on a lonely farmstead, no neighbors near, to keep a spark alive, so great Odysseus buried himself in leaves and Athena showered sleep upon his eyes. OTHER DEVICES Personification occurs in almost every book when "Dawn" arises with her "rose-red fingers". As the gods have distinctly human characteristics, they display a non-linguistic personification even amongst themselves. They also appear disguised as people, and the Mentor we know is always the "personification” of Athena. Other things are frequently personified: "Sleep" looses "Odysseus' limbs, slipping the toils of anguish from his mind"; "East and South Winds clashed, and the raging West and North/sprung from the heavens, roiled heaving breakers up." 8 Metaphors are less striking in The Odyssey than similes. They are frequently embedded in verbs: "Nine years we wove a web of disaster"; "that made the rage of the monster boil over"; "his mind churning with thoughts of bloody work"; "Terror blanched their faces" (note the personification of terror). Odysseus is "fated to escape his noose of pain," and when he finds himself near the land of the Laestrygonians, he places his ship "well clear of the harbor’s jaws." Symbols are also associated with the gods. Eagles, usually swooping down, are often seen as manifestation of Zeus, but they are also portents that foreshadow Odysseus' return. As such they need interpreters gifted at reading signs (Halitherses, Theoclymenus, Helen, and even Odysseus, himself, when he interprets a dream of Penelope's). Many gods are associated with specific symbols: Zeus, the thunderbolt; Poseidon, the scepter; Apollo and Artemis, arrows; Athena the loom. The loom itself is associated with all the major female characters, Calypso, Circe, Helen and, most memorably, Penelope. Themes/Motifs/Symbols to look for as you read: Hubris / Pride and Honor The Hero’s Journey Respect for the Gods Crime / Punishment / Revenge / Justice Respect for the Dead Fate / Destiny / Prophesy Hospitality: The Guest / Host Relationship Loyalty More than Just a Hero Obviously Odysseus is an epic hero, for his ability to survive adventures in which his companions die, his prowess in combat, and his being a favourite of the gods all distinguish him as worthy of the name. Homer has, however, given to his audience a man who has feelings and motivations that go beyond merely attaining glory. One of the poet’s strengths is his ability to create a believable hero who loves his family and country, is a sensitive and patient person, and possesses frailties that we all recognize as human. As you read The Odyssey, find specific evidence that demonstrates the multi-faceted person Homer has created. Note evidence (either by annotating or use of sticky notes) that clearly depict: Odysseus as a family man As a patient, compassionate man Odysseus as capable of human weakness 9 THE ODYSSEY: General Study Questions 1. How does Homer establish the significance of the story he is about to tell? How does he maintain interest in the tale as it unfolds? Keep in mind that "suspense" is not a key factor in Greek literature since the audience usually knows from the outset how things will turn out. 2. How would you characterize the narrator, the fictive "Homer" whose voice we imagine as singing the verses of The Odyssey? 3. What direct references to the craft or performance of poetry do you find in The Odyssey? What do they tell us about the importance of poetry in Homer's day? In responding, consider also indirect references such as the ones the text makes to weaving and singing - after all, Homer himself might be said to "weave" his story, stitching together the various episodes and characters into a meaningful tale; and of course an epic bard sings his verses. 4. What qualities does the text hold up as heroic? Keep track of heroic qualities and the episodes in which they are most evident and necessary. Are there different kinds of heroism? If so, what is the distinction between the different kinds of heroism? 5. What kinds of behavior are treated as contemptible in The Odyssey? Keep track of these qualities and the characters who embody them. Find episodes where contemptible behavior occurs. 6. How does the poem represent mortal women? Since Penelope is the most important woman in The Odyssey, what qualities does she possess, and how does she respond to the troubles she faces? (Some of the other women are of note, too - Eurycleia the serving woman, the faithless maidservants, Nausicaa the Phaeacian princess, and Helen of Sparta, Menelaus' queen, whose elopement with Prince Paris sparked the Trojan War.) 7. How do Homer's gods think and behave? How do their actions and motivations differ from the conception of god in other religions of which you have knowledge? What role do the Homeric gods play in human affairs, and what is the responsibility of humans with respect to those gods? 8. What can you gather from The Odyssey about the way the Homeric Greeks lived their daily lives? About how they governed themselves and what sorts of social distinctions there may have been among the citizens of Ithaca? For example, how important is the royal household to the rest of the Ithacans? 9. Keep track of The Odyssey's structure - make a diagram or chart of some kind that illustrates the main episodes and their relation to one another. To get you started, the epic is divided into three main parts or plot-complexes: 1) The maturation of the young prince Telemachus; 2) The wanderings of Odysseus - mostly recounted as past events; and 3) Odysseus' return to Ithaca and re-establishment of his authority as king. Consider also that although the poem's action takes place over the course of forty days, the text refers when necessary to events spanning twenty years - i.e. from the beginning of the Trojan War on through the ten-year wanderings of Odysseus after the ten-year war. 10 THE ODYSSEY: Homer / Translated by Robert Fagles Book by Book Summaries BOOK 1: “Athena Inspires the Prince” Scene: Calypso's island (briefly), Olympus (briefly), Ithaca, (mainly) Important Characters: Gods: Poseidon, Hermes, Athena/Mentes, Zeus Mortals: Telemachus, Mentes (Athena): King of the Taphians, friend of Odysseus, Penelope, Eurycleia (nurse) Phemias (the singer), the "suitors," especially Antinous and Eurymachus. The book begins with the invocation to the Muse followed by Athena's plea to Zeus to allow her favorite mortal Odysseus to travel home from Ogygia, where he has been held captive for seven years by the nymph Calypso. Zeus agrees but not without insisting the trip be arduous. He does not want to enrage the absent Poseidon, who is angry at Odysseus for having blinded his son, the Cyclops, Polyphemus. Athena goes to Ithaca to spur Telemachus, Odysseus' son, into action and start him toward manhood. There we meet the suitors of Odysseus’ wife, Penelope, who are abusing the rules of hospitality. We also learn that Penelope has done whatever she could to keep them from taking her hand in marriage. Almost everyone on Ithaca believes Odysseus to be dead. BOOK 2: “Telemachus Sets Sail” Scene: Ithaca Characters: Eurycleia, Mentes/Mentor/Athena, Telemachus, Antinous, Halitherses, Eurymachus. Summary: For the first time, Telemachus assembles all the suitors. Telemachus wants the suitors to feel ashamed. The loudest suitor is Antinous, who yells that all this is Penelope’s fault. Penelope promised to marry again when she is finished weaving, but she weaves every day and takes apart her weaving every night. Telemachus promises to punish the suitors. Two eagles (Zeus’ birds) come down and the suitors panic. The eagles are a sign that Zeus is helping Telemachus. However, some men still do not believe Telemachus. Telemachus promises that his mother will marry a new husband if he learns his father is dead. He plans to take a trip to find out what happened to his father, so he asks the suitors for a ship and crew of sailors. Athena disguised as his friend Mentor, helps him get the ship and crew (sailors). During the night, Telemachus secretly sails away. BOOK 3: “King Nestor Remembers” Telemachus and Mentor sail to Pylos, where they meet King Nestor and his sons. In a fatherly manner, Nestor tells Telemachus the sad story of Agamemnon's coming home after the wars. Penelope is loyal to her husband, but Agamemnon's wife, Clytemnestra, was disloyal. When King Agamemnon arrived home, his wife's new lover killed him. Nestor explains that Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus traveled together for a while and then went separate ways. The last time Nestor saw Odysseus, he was going to join Agamemnon. Since Menelaus was the last one to see Odysseus, Nestor suggests that Telemachus ask Menelaus about Odysseus. He gives Telemachus a chariot and asks his son to help him with his journey to Menelaus' kingdom in Sparta. Mentor (Athena) leaves. All of a sudden, everyone at the feast realizes that Mentor is really Athena in disguise, so Nestor sacrifices (kills) a gilt-horned bull to honor her. BOOK 4: “The King and Queen of Sparta” When Telemachus arrives in Sparta, people are celebrating the double wedding of Menelaus' son and daughter with a huge feast. Menelaus does not know who Telemachus is. When Menelaus talks about how much he misses Agamemnon 11 and Odysseus, Telemachus begins to cry. Then Menelaus sees how much Telemachus looks like his father. Telemachus and his father have more in common as the father's journey home parallels the son's journey toward manhood. After dinner, Menelaus tells Telemachus the news. He says Agamemnon was killed and Odysseus was forced to stay on Calypso's island. Old Menelaus speaks sadly about the losing his friend. As Nestor and Menelaus get older, the soldiers change and their friendship becomes more important. Back in Ithaca, Penelope's suitors know that Prince Telemachus is looking for his father. They are afraid that the young prince might not allow them to marry Penelope, so they try to stop Telemachus. Penelope worries about her son, but Athena sends her a dream to keep her calm. BOOK 5: “Odysseus – Nymph and Shipwreck” On Olympus, the gods again meet. Athena again asks Zeus to help Odysseus, and mighty Zeus agrees to send Hermes to Calypso. Calypso is in love with Odysseus. She has promised that he will live forever if he stays with her. She has kept him in her smooth caves for years. She obeys Zeus' orders and promises to help Odysseus return home. Although the reader hears about Odysseus, Book 5 is when the reader first sees him. He is crying for his family when Calypso says she will set him free. Odysseus is afraid that she will not really let him go, so he talks sweetly to her. He says he really likes her, but it is his duty to leave. She gives him her veil, a good luck charm, for protection. He builds a boat and sails away. Poseidon returns to find Odysseus at sea. He is so angry that he creates a storm which breaks apart Odysseus' small boat. Odysseus holds on to a floating board and is saved by Athena. Athena guides him to the beach on the island of Scheria, land of the Phaeacians. Half-dead and very tired, he gets to the beach and then faints. BOOKS 6 to 8 Athena visits an island princess in her dream. She tells her to go to the beach where she finds Odysseus. The princess brings him home to her family who gives him food and clothes. Then he goes to the city to see the King and Queen. This island is like heaven because of its beauty and the people’s hospitality. It is the perfect place for Odysseus to rest. The islanders' hospitality is more impressive because they do not know that he is famous. Odysseus shows he is a hero. He proves he is smart and strong with a good attitude before he gives his real name. After he gives his name, he tells the story of his past adventures. BOOK 9: “The One-Eyed Giant’s Cave” Odysseus’ story of his adventures begins after the Trojan War when he escapes from Troy. Storms keep him at sea for many days. Finally, his ships land at the island of the Lotus-Eaters. Anyone who eats Lotus becomes tired and forgetful because Lotus is a strong drug or opiate. The sailors eat the Lotus and are drugged. Odysseus and the other men from the ship pull their weaker, drugged shipmates off the island. Next, the ships sail to the islands of the Cyclops, a group of one-eyed giants. Trapped with his men in one of the caves, Odysseus watches the giant Polyphemus eat handfuls of his men. Odysseus has a clever plan to introduce himself to Polyphemus as “Nobody” and get him drunk on strong wine. Odysseus and his men poke out the eye of the sleeping Cyclops with a sharpened mast (pole that holds the ship’s sail). When the other Cyclopes hear the screams, they ask who is doing this. When they hear the answer “Nobody”, they think it must be the gods. Polyphemus cannot see, so he guards the cave door to catch the men who blinded him. He touches each sheep before he lets it out to graze (eat grass). Odysseus and his men escape by holding on to the bellies of the sheep. The escape is perfect, but Odysseus makes a big mistake as he is leaving. He yells out his true name. Then, Polyphemus asks his father, Poseidon, to punish Odysseus. Poseidon increases the difficulties for Odysseus, so he cannot get back to his homeland. BOOK 10: “The Bewitching Queen of Aeaea” Odysseus stops on the island of Aeolus, King of the Winds. When Odysseus leaves the island, Aeolus gives him a gift. It is a bag of all the bad winds. If these winds are gone, Odysseus can have clear weather for his trip home. Odysseus can see Ithaca from his ship. However, while Odysseus is sleeping, his sailors open the bag because they think Aeolus' bag is full of treasure. The winds escape and the wind storm blows the ships back to Aeolus. Aeolus will neither forgive Odysseus nor let him back on the island. Like Odysseus' pride on the Cyclops' Island, the sailors' greed has 12 serious consequences for the journey. Next, the ships sail to the island of the Laestrygonians. These clever cannibals attack and destroy all but Odysseus’ ships. His ships land on the island of Aeaea where the goddess Circe lives. A group of men go to see what is on the island, but only one man returns to the boat. The man tells Odysseus that a beautiful goddess has turned the men into pigs. Odysseus sets off to save his men. He meets Hermes, the gods’ messenger, who looks human. Hermes gives him advice about Circe and an herb to protect him from Circe’s magic. Odysseus finds Circe. When Circe cannot turn Odysseus into a pig, she agrees to change the pigs back into men. Circe falls in love with Odysseus and keeps him on the island for one year. Finally, she agrees to help him return home. She sends him to ask for help from Tiresias in Hades near the end of the world BOOK 11: “The Kingdom of the Dead” At the edge of the world, the crew makes a sacrifice and waits for the blind oracle Tiresias. The dead come up from the earth because they get hungry when they smell sacrificial blood. Tiresias comes up too. He tells Odysseus that he faces more difficulties. Tiresias tells him he must make peace with Poseidon if he wants to return to Ithaca. He also says that when Odysseus does return to Ithaca, no one will know him and he will have no friends. Here, the hero moves between mortals (humans) and gods, and between life and death. However, Odysseus shows that he is very human (a mortal) as he struggles and fails, because of temptation and his pride. This is a symbolic (has a deeper meaning) voyage into death and then back to life. He has experiences that humans cannot have, so he becomes supermortal (super human). BOOK 12: “The Cattle of the Sun” Odysseus and his crew return to Aeaea to bury one of the sailors and about the problems he will face. Circe and Tiresias predict that the ship will pass the islands of the Sirens. Sirens are bird-like women whose beautiful songs attract sailors to dangerous rocks. The sailors die when the ship hits the rocks. Odysseus blocks his men's ears with beeswax to save them from temptation, but he wants to hear the beautiful songs. He asks his men to tie him to the ship, so he can safely listen to the songs. This shows that Odysseus' loves adventure. He wants to go home, but he also loves adventure, so he lives fully but not happily. The ship safely passes the Sirens and moves on to the next challenge, a narrow strait between Scylla, a six headed monster, and Charybdis, a whirlpool. The ship stays away from Charybdis, but Scylla kills some of the sailors. The ship survives this danger and face another challenge. It lands on the island of the sun god Helios. The hungry crew kill the oxen of the sun god even though Circe and Tiresias told them never to kill the oxen. The ship and crew are destroyed by a thunderbolt from Zeus. Only Odysseus survives, washing up after nine days at sea upon Calypso's island. Thus ends Odysseus' tale; the rest of the story we know from Homer. BOOKS 13 to 16 The Phaeacians give Odysseus gifts and a magic ship to take him to Ithaca. Poseidon gets angry because they are so kind to Odysseus, so Poseidon punishes the Phaeacians. At last Odysseus reaches his homeland. Now, his difficult world adventures end and his problems at home begin. Odysseus is welcomed home by Athena. She disguises him as a beggar so that he can secretly find out what is happening at his house. He looks for his trusted servant Eumaeus in the mountains. Telemachus also returns home from his travels and looks for Eumaeus. Father and son find each other. Odysseus tells his son who he really is. Telemachus’ journey has helped Odysseus' return home and Telemachus’ experiences have changed him into a mature man. Father and son plan Odysseus' return home and plan their revenge on Penelope's suitors. To reach this goal, they agree to keep Odysseus' identity a secret from everyone, even Penelope and Odysseus' father, Laertes. BOOK 17: “Stranger at the Gates” Telemachus returns to his home and tells his mother about his adventures. She welcomes him with excitement and sadness. The situation at home is terrible. Even though a soothsayer (fortune teller) correctly says Odysseus will come home in disguise, Penelope is afraid Odysseus will not return. Odysseus and Eumaeus return to town and pass Odysseus' thin but still faithful dog. The kingdom is not well. Odysseus is disguised as a beggar, so he asks for food at the suitors' feast. Everyone gives food to the beggar except for 13 Antinous. Antinous hits him and sends him away. Revenge on these suitors, especially Antinous will be fair and feel sweet. Penelope shows her hospitality and her loyalty to her husband, by asking the beggar for news of Odysseus. BOOK 18: “The Beggar-King of Ithaca The suitors make the disguised Odysseus fight another beggar in a boxing match. Neither man wants to fight, but Odysseus ends up breaking the man's jaw. Penelope yells at the crowd of suitors for staging the fight. In anger, she yells at them for spending all her husband's money. Some suitors are ashamed, but none leave. In the end, the suitors drunkenly laugh at the disguised Odysseus. Odysseus feels angry, but hides his feelings. Everyone is hateful for the way they treat the poor. They do not show hospitality to the low. BOOK 19: “Penelope and Her Guest” The suitors go to bed. Odysseus and Telemachus lock up all the weapons in the house. Penelope tells the "beggar" about her problems since Odysseus left. Odysseus cannot tell Penelope who he is if he wants to successfully get back his power. Odysseus tells her a soothing story. Penelope asks an old, trusted servant to wash the beggar's feet. When she does, she knows her old master by a scar on his foot. Odysseus tells the servant to keep this secret from Penelope. Penelope tells Odysseus about her plan to choose a suitor. She will marry the man who can shoot an arrow through a row of twelve axes, something that her Odysseus could do. She is not happy, but she must remarry to keep the kingdom safe. Odysseus agrees that it is a good challenge. He says that her husband will return before the contest ends. Athena brings this dream to her, but Penelope cannot believe the beggar's words. She cries herself to sleep. BOOK 20: “Portents Gather” Odysseus cannot sleep with his anger at the suitors. He tries to decide which servants are still loyal to him and which are not. Athena comes to calm him. She will help him take revenge. Penelope cannot sleep, so she asks the gods to save her from remarriage. Athena makes the suitors act even worse to further anger Odysseus. At lunch, the suitors insult their host Telemachus. He proves he is no longer a weak boy. Telemachus stands tall and predicts that the suitors' good lives will soon end. Athena makes the guests laugh painfully and out of control. The fortune teller says this sign means death is coming, but the suitors laugh at his words. The tension grows as the suitors wait for the contest for Penelope's hand and Odysseus waits for revenge. BOOK 21: “Odysseus Strings his Bow” Penelope takes Odysseus' great bow from its locker and is flooded by strong memories of her husband. In the great hall she announces the beginning of the contest for her hand in marriage. The suitor who can send an arrow through twelve lined axes will win. Telemachus sets up the axes with skill. With revenge so close, he can hardly hide his joy. He invites the suitors to their death. He tells them to string the bow and win the prize. Telemachus tries to string the huge bow and stops at the silent order of Odysseus. As clever as his father, he leaves the task to the "real men." The worst suitor, Antinous, encourages the others toward this challenge. The irony of the situation is clear: Antinous is pushing everyone to step up and string the massive bow - the same bow that Odysseus will use to kill the suitors. Odysseus, meanwhile tells his two most trusted servants his true identity. As they cry for joy, he asks for their help with revenge. The servants will give Odysseus the bow, protect the women, and lock the gates until the revenge is finished. Antinous decides to wait until the next day to string the huge bow. Odysseus says he will try. Antinous warns he will give a terrible punishment if the beggar even touches the bow. Penelope says the suitors should be ashamed of their behavior. She promises that, if the beggar succeeds, she will give him supplies and safe passage out of town. This act shows her gracious and gentle manner. It also shows that she understands man's freedom is important. Telemachus also shows his power over the situation. While Odysseus was gone, he has grown up into a prince ready to be as good a king as Odysseus. Proud of her son, Penelope goes to her bedroom. Athena soothes her teary eyes with gentle sleep. Odysseus takes the bow. He checks it, smoothly strings it and sends an arrow through the axes. Zeus sends a one thunderclap through the air and Odysseus laughs to himself. The suitors are no longer in a partying mood. Still disguised as a beggar, Odysseus calls Telemachus. The father and son prepare for their victory. 14 BOOK 22: “Slaughter in the Hall” Odysseus takes his revenge. First, he shoots Antinous with an arrow. Antinous is holding a golden cup of Odysseus’ wine. It falls to the floor. The meat and bread fall off the table on to the floor and soak up the spilled blood. Homer uses these images of the suitor's "free lunch" to show the irony of Odysseus' revenge. The suitors are angry about the “beggar’s” careless shot. When Odysseus gives his true name, they become afraid. Odysseus kills each suitor with his arrows though they try to hide from him. Telemachus helps his father fight. Odysseus knows the importance of human life and death. He has planned to kill these men for good reason. When all the suitors have been killed, Odysseus orders the disloyal women of the house to carry the bodies away and to wash the courtyard clean of the blood of his enemies. Then Odysseus hangs these women. As his servants clean the house with fire, Odysseus cries. He is finally at home in his kingdom. BOOK 23: “The Great Rooted Bed” Eurycleia, a loyal servant tells Penelope that Odysseus has come home. She hurries to the hall to see him. Odysseus is dressed like a beggar, covered in blood, and is twenty years older, so he does not look like her husband. To find Odysseus' identity, she cleverly tests him. When she orders Eurycleia to move the wedding bed into the hall, Odysseus knows it is a trick. The bed is made from the bottom of a giant tree rooted in the ground, so Odysseus says no one can move the bed. Penelope is convinced of his identity. The reunited husband and wife spend the long evening making love and informing each other of their twenty years' adventures. Athena delays the dawn until Odysseus is satisfied and tired. The difference between how the men and women are treated may seem strange to a modern reader. Odysseus has many sexual adventures with goddesses, but Penelope never questions him. On the other hand, Odysseus questions Penelope’s faithfulness. In spite of twenty years of intense courtship by hundreds of men, a wife is expected to be loyal. Odysseus wakes his son and attendants in the morning. He is going to visit his father, Laertes, in the country. Athena hides the men in darkness as they walk. Examine Ritsos’ poem as it relates to Homer’s epic poem, particularly Book 23. Penelope’s Despair It wasn’t that she didn’t recognize him in the light from the hearth: it wasn’t the beggar’s rags, the disguise – no. The signs were clear: the scar on his knee, the pluck, the cunning in his eye. Frightened, her back against the wall, she searched for an excuse, a little time, so she wouldn’t have to answer, give herself away. Was it for him, then, that she’s used up twenty years, twenty years of waiting and dreaming , for this miserable blood-soaked, white-bearded man? She collapsed voiceless into a chair, slowly studied the slaughtered suitors on the floor as though seeing her own desires dead there. And she said “Welcome,” hearing her voice sound foreign, distant. In the corner, her loom covered the ceiling with a trellis of shadows; and all the birds she’d woven with bright red thread in green foliage, now, on this night of return, suddenly turned ashen and black, flying low on the flat sky of her final enduring. Yannos Ritsos September 21, 1968. 15 Summary of Book 24: “Peace” Hermes brings the ghosts of Penelope's dead suitors to the underworld. In Hades, the ghosts of the Trojan War tell about their past adventures. Agamemnon asks why Ithaca's best men are in the underworld. The suitors explain that Odysseus has returned. Agamemnon is impressed with Penelope because she was so loyal to Odysseus. Meanwhile, Odysseus finds his father who is working as a woodsman. Hiding his identity, Odysseus asks the old man about the fate of Ithaca and its king. These questions make the old man sad because he thinks his son is still missing. Finally, Odysseus runs into his Lather's arms, but Laertes does not believe he is Odysseus. Odysseus shows an old scar and the two men cry into tears of happiness. The people in Ithaca meet. Many people want peace between Odysseus and the families of the dead suitors, but other families want revenge. Since Odysseus is visiting his father, they go to Laertes' home to get revenge. Athena asks her father to judge Odysseus. Zeus thinks Odysseus acted fairly, so Athena continues to protect him. Zeus' judgment decides questions about what is right and what is wrong in a system of honor and justice. This system uses revenge to punish wrong doers. Zeus is the most powerful, so he has the last word. Athena comes down to earth to stop the fighting. The people are afraid of Athena, so they run away. Odysseus begins to chase them, but Athena tells him to control himself. She is supported by a thunderbolt from Zeus. When Odysseus at long last puts down his weapons it is a great relief; this act seems to signal a new era for man. Athena, disguised again as Mentor, negotiates a lasting peace for the island. The struggle is finally over. 16