Student-Athlete Compensation in College Athletics:

advertisement

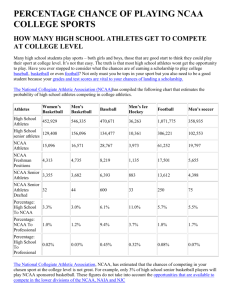

Student-Athlete Compensation in College Athletics: An Examination of Edward O’Bannon, et al. v. NCAA; Electronic Arts Inc.; and Collegiate Company Zach Pogust Professor Jordi Comas Mgmt 302: The Stakeholder Organization 12/18/14 Zachary Pogust 2 Executive Summary The NCAA was founded in 1905 by sixty-two college presidents with the intention of creating a uniform set of rules to regulate intercollegiate football. Today, the association monitors roughly eleven hundred member schools, regulating intercollegiate athletic competitions in roughly two-dozen sports (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 2). According to the NCAA manual, the association seeks to “initiate, stimulate and improve intercollegiate athletic programs for student-athletes and to promote and develop educational leadership, physical fitness, athletics excellence and athletics participation as a recreational pursuit” (NCAA Academic and Membership Affairs Staff, 15). To achieve these objectives the NCAA enforces a set of rules and regulations governing athletic competitions and the actions of its member-school’s student-athletes. Among other things, these rules prohibit studentathletes from receiving any compensation resulting from their athletic performance and place a limit on the size of the athletic scholarships that the member-schools can provide to their student-athletes. These rules and regulations remained relatively untouched from 1973 (when the NCAA began to re-organize itself into the three distinct divisions that are still in existence today: Division 1, II & III) and 2009 (when a group of current and former FBS football and Division 1 basketball student-athletes sought to challenge the NCAA restrictions, claiming that they violate the Sherman Antitrust Act). This policy paper is directed at the NCAA and will first proceed by examining the Edward O’Bannon, et al. v. NCAA; Electronic Arts Inc.; and Collegiate Licensing Company case, including the assertions of the Plaintiffs and Defendants, and ultimately discussing the decision issued by the court. Next, the evolution of the collegiate sports industry (specifically FBS football and Division 1 basketball) will be reviewed as a way to 3 show why this court remedy is necessary and can even benefit the NCAA. Lastly, The policy paper will provide a few strategic recommendations for the NCAA that, in combination with the court injunction, will help rid the them of the contradictions that exist between their stated mission/objective and consequences that result from their regulations. 4 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 2 EDWARD O’BANNON, ET AL. V. NCAA; ELECTRONIC ARTS INC.; AND COLLEGIATE LICENSING COMPANY ............................................................................................................................. 5 CASE OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................................5 SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT ....................................................................................................................................6 THE MARKETPLACE .................................................................................................................................................7 College Education Market .................................................................................................................................. 7 Group Licensing Market ...................................................................................................................................... 8 THE CHALLENGED RESTRAINT ..............................................................................................................................8 ASSERTED PURPOSES OF RESTRAINT ................................................................................................................ 10 REMEDY & CONCLUSION ...................................................................................................................................... 10 WHY THIS CHANGE? ............................................................................................................................ 11 EVOLUTION OF THE INDUSTRY ........................................................................................................................... 11 NCAA: The Best Monopoly in America ........................................................................................................12 “Amateurism” and the “Student-Athlete”..................................................................................................13 The Black Market ..................................................................................................................................................15 RECOMMENDATIONS........................................................................................................................... 16 DECISION TO APPEAL ........................................................................................................................................... 16 ONE-YEAR VS. FOUR-YEAR SCHOLARSHIP OPTION ........................................................................................ 17 SCHOLARSHIP REQUIREMENT ........................................................................................................................ 18 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................................... 19 FIGURES, DATA, TABLES .................................................................................................................... 21 WORKS CITED ........................................................................................................................................ 23 5 Edward O’Bannon, et al. v. NCAA; Electronic Arts Inc.; and Collegiate Licensing Company Case Overview Edward O’Bannon, et al. v. NCAA; Electronic Arts Inc.; and Collegiate Licensing Company is an antitrust class action lawsuit that was initiated in 2009, however it wasn’t until August 8th, 2014 that United States District Judge Claudia Wilken entered a decision. The Plaintiffs in the case consist of twenty current and former college student-athletes, all of whom play or played for an FBS football or Division 1 men’s basketball team between 1956 and present (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 6). The Plaintiffs brought about the case to challenge the NCAA’s long-standing rules restricting compensation for elite men’s football and basketball players at the collegiate level. More specifically, the Plaintiffs contend that the regulations placed upon them violate the Sherman Antitrust Act and that they should be entitled to receive a “share of the revenue that the NCAA and its members schools earn from the sale of licenses to use the student-athletes’ names, images and likenesses in videogames, live game telecasts, and other footage” (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 1). The defendants in the case are the NCAA, Electronic Arts Inc. and the Collegiate Licensing Company, however the NCAA is the primary defendant and at the center of this case. The NCAA denied the claim that its rules restricting compensation violate the Sherman Antitrust Act and assert that the regulations are necessary to “uphold its educational mission and to protect the popularity of collegiate sports” (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 2). “Wilken was not asked to rule on the fairness of a system that pays almost everyone but the athletes themselves. Instead, the case was centered on federal antitrust law and whether the prohibition against paying players 6 promotes the game and does not restrain competition in the marketplace” (ESPN.com News Services). Although the case raises important questions and considerations regarding athletic competition on the field and court, it is principally about the rules governing competition in a different arena – the marketplace (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 1). Sherman Antitrust Act In order for one to understand the framework through which this case was viewed and ultimately decided by Judge Wilken, it is important to understand the basic idea of the Sherman Antitrust Act and its intended purpose. The Sherman Antitrust Act is a federal anti-monopoly and anti-trust statute that was passed in the Senate on July 2nd, 1980. It was initially established to alleviate concern regarding monopolies dominating America’s free market economy throughout the late 1800s and was viewed as a way to combat anti-competitive practices. The act was the first Federal act to outlaw monopolistic business practices, specifically trusts (“Sherman Anti-Trust Act [1980]”). According to the government-produced article entitled, “Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1980),” a trust, at the time, was “an arrangement by which stockholders in several companies transferred their shares to a single set of trustees. In exchange, the stockholders received a certificate entitling them to a specified share of the consolidated earnings of the jointly managed companies” (“Sherman Anti-Trust Act [1980]”). Trusts came to dominate various major industries, destroying competition along the way. Section 1 of the act states, “[e]very contract, combination in the form of trust or other-wise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal” ("Transcript of Sherman Anti-Trust Act [1890]”). 7 Congress derived its power to pass the Sherman Act through its constitutional authority to regulate commerce. Therefore, the Sherman Act can only be used when the conduct in question restrains or substantially affects…interstate commerce...To satisfy this jurisdictional requirement, the Pmust show that the conduct in question occurs during the flow of interstate commerce or has an appreciable effect on some activity that occurs during interstate commerce. (“Antitrust”) The Sherman Antitrust Act, which is at the heart of most federal antitrust litigation in the United States, is the principle area of focus in this case, as the Plaintiffs attempt to prove that the NCAA restrictions restrain trade in the marketplace. The Marketplace As is the case with any antitrust litigation, the Plaintiffs must identify an economic market that has been impaired by the restraint of trade. The Plaintiffs in the case allege that the NCAA has restrained trade and competition in two national markets: the “college education market” and the “group licensing market.” “Although these alleged markets involve many of the same participants, each market ultimately involves a different set of buyers, sellers and products” (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 7). College Education Market Evidence presented at trial, including testimony from both experts and lay witnesses, or witnesses not testifying as experts, established that FBS football programs, along with Division 1 basketball programs, both compete to recruit the best high-school players. The schools act as the sellers and the high-school athletes act as the buyers in this scenario. “[T]hese schools compete to sell unique bundles of goods and services…[including] scholarships to cover the cost of tuition, fees, room and board, books, certain school supplies, tutoring and academic support services” (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 7). Additionally, they compete to sell access to high-quality athletic coaching, medical treatment, state-of-the-art 8 athletic facilities and even the opportunity to compete in front of large crowds and television audiences (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 7). In exchange for these unique bundles of goods and services, the recruits agree to provide their respective schools with their athletic abilities and allow for their names, images and likenesses to be used for commercial and promotional purposes. Additionally, the court found that no viable substitutes exist, as the bundle of goods and services offered by schools with major sports programs is truly unique. Thus, these schools comprise a market that is relevant to the discussion of the alleged violations. Group Licensing Market The Plaintiffs argue that in the absence of the NCAA restrictions on student-athlete compensation, athletes would be able to offer group licenses to be sold to their respective schools, third-party licensing companies, or media companies hoping to use athletes’ names, images and likenesses (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 13). The Plaintiffs identify three submarkets in which group licensing would be practical: 1. Live game telecasts 2. Videogames 3. Game re-broadcasts, advertisements and other archival footage The Plaintiffs show that a demand exists for the rights to each of these three potential grouplicensing submarkets to which the court agrees. The Challenged Restraint In the next section of the ruling, “The Challenged Restraint,” Judge Wilken discussed the means by which the NCAA is able to impose limits on their student-athletes, and the implications of these limits. To start, the NCAA “prohibits any student-athlete from receiving ‘financial aid based on athletics ability’ that exceeds the value of a full ‘grant-in-aid”’(Edward O’Bannon v. 9 NCAA, 19). According to the NCAA bylaw 15.02.5, a full “grant-in-aid” is defined as “financial aid that consists of tuition and fees, room and board, and required course-related books” (NCAA Academic and Membership Affairs Staff). The NCAA also prohibits any student-athlete from receiving financial aid in excess of his “cost of attendance,” “an amount calculated by an institutional financial aid office, using federal regulations, that includes the total cost of tuition and fees, room and board, books and supplies, and other expenses related to attendance at the institution” (NCAA Academic and Membership Affairs Staff). Additionally, the NCAA bylaws state that an athlete may not receive any compensation due to their publicity, reputation, fame or personal following they may have obtained because of athletic performance or ability and may not endorse any commercial product, regardless of whether or not they receive compensation for it (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 21). After an examination of these restraints by Dr. Noll, the Plaintiff’s economic expert, he explained, “because the NCAA has the power to and does suppress the value of athletic scholarships through its grant-in-aid rules, it has increased the prices schools charge recruits” (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 21). The court subsequently agreed, claiming the price-fixing agreement among FBS football and Division 1 basketball schools are harmful to studentathletes at these schools. In the complex exchange represented by a recruit’s decision to attend and play for a particular school, the school provides tuition, room and board, fees and book expenses, often at little or no cost to the school. The recruit provides his athletic performance and the use of his name, image, and likeness. However, the schools agree to value the latter at zero by agreeing not to compete with each other to credit any other value to the recruit in the exchange. This is an anticompetitive effect. Thus, the Court finds that the NCAA has the power – and exercises that power – to fix prices and restrain competition in the college education market that Plaintiffs have identified. (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 22-23) 10 Asserted Purposes of Restraint The NCAA attempts to defend its restrictions by claiming they are necessary to preserve its tradition of amateurism, maintain a competitive balance, promote the integration of academics and athletics and increase the total output of its product. In regard to each of these, the court did not find NCAA’s evidence to be sufficient in justifying the challenged restraint and believe less restrictive rules regarding player compensation can still allow for these corporate objectives to be met. Remedy & Conclusion The Court found that the restraints imposed by the NCAA do, in fact, violate antitrust law. Accordingly, the Court entered an injunction to remove an unreasonable element of restraint imposed by the NCAA on its member schools and student-athletes. FBS football and Division 1 basketball teams will not be prohibited from offering their recruits a limited share of the revenues generated from the use of their names, images and likenesses in addition to a full grant-in-aid (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 96). While the NCAA will be allowed to set a cap on the amount of compensation a student-athlete may receive while enrolled in school, the NCAA will not be permitted to set this cap below the cost of attendance (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 96). Additionally, the NCAA will be prohibited from enforcing rules that prevent its members schools and conferences from offering to deposit a limited share of licensing revenue into trust funds for their student-athletes, payable once they are no longer enrolled. The NCAA will also be allowed to set a cap on the amount of money that may be held in trust, yet it cannot be less than $5,000 for every year that the student-athlete remains academically eligible to compete (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 96). Lastly, the injunction 11 will not preclude the NCAA from enforcing its existing rules – or enacting new rules – to prevent student-athletes from using the money held in trust for their benefit to obtain other financial benefits while they are still in school…and will not preclude the NCAA from continuing to enforce all of its other existing rules which are designed to achieve its legitimate precompetitive goals. (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 97). Why This Change? Evolution of the Industry With each new college football bowl season we are reminded that the story of intercollegiate athletics in higher education is rich in history, anchored in tradition, and tied to the heart of university communities. As enduring as the storied rivalries, larger than life characters, bruising nature of the game itself, and fervor of fans are, so too are the issues associated with the compensation of athletes for their services. (Huma & Staurowsky, 4) It’s time we take a step back, strip away all of the trivial symbolism and tradition of college athletics, and analyze the core issues at play. While the feelings of nostalgia and admiration of imperfect athletic performance are part of what makes college sports so popular and unique, we must now evaluate the current state of college athletics and the billion-dollar business it has become in order to understand why the changes initiated by the court were necessary. Major collegiate sports industries, such as American college football, have seen consistent growth since their founding. As seen in Figure 1, revenue generated by college athletics at FBS schools has grown tremendously over the past few years. The University of Alabama, for example, generated more revenue from their athletic programs last year than did any U.S. or Canadian professional ice-hockey team (McDuling). FBS football and Division 1 basketball programs have become the most popular of all collegiate sports and have generated millions of dollars of revenue for NCAA member schools. As seen in Figure 2, men’s football and basketball teams often account for up to 50% to 75% of a school’s 12 revenue generated from all of their athletics. For this reason, the case and injunction issued only pertain to these two sports within Division 1 member schools. As college athletics has developed into a multi-billion dollar business, the NCAA has not made the necessary changes to their governance that is needed to keep up with the everexpanding industry that they oversee. Up until the decision issued by Judge Wilken, the NCAA had exercised unilateral authority and suppressed the value of the very athletes who are the marketable commodities on which their member colleges and universities build their sports enterprises (Huma & Staurowsky, 6). The examination of the different actors within this multi-billion dollar industry, and how their roles have changed over time, will further illustrate why this class action lawsuit was necessary. NCAA: The Best Monopoly in America Back in 2002 a panel of Harvard University economists claimed the NCAA was the clear-cut choice for the best monopoly in America (Barro). Under the guise of amateurism the NCAA has successfully stifled financial competition in college sports (Barro) and has handed out hefty paychecks to just about everyone in the industry except for the actual laborers themselves. Additionally, and as discussed in the findings of facts and conclusions of law in the case, the NCAA has used its power to suppress the value of athletic scholarships, ultimately increasing the prices schools charge recruits. With one agency (the NCAA) governing all of the suppliers that offer a unique bundle of goods and services, there remains no incentive for the NCAA to improve and meet the demands of their consumers, a common quality of most monopolies. As the only governing body in an ever-growing industry, the NCAA’s decision to resist making changes to their operations seems to be self-serving and is exactly what they 13 had always done. The NCAA has relied on the same arguments over the years to defend these self-serving antics; “[a]t the core of every position taken by the NCAA regarding athlete compensation is its principle of amateurism” (Huma & Staurowsky, 11) and idea of the student-athlete. “Amateurism” and the “Student-Athlete” While the NCAA has repeatedly relied on these two concepts to support and defend its decision making process, they have done a great deal to undermine their own idea of amateurism and the concept of the student-athlete. To start, NCAA leaders have often been unable to clearly articulate a logical rationale for its version of amateurism. Below is an excerpt from an interview that took place between former NCAA President Myles Brand and Sports Illustrated columnist Michael Rosenberg in 2011: "They can't be paid." "Why?" "Because they're amateurs." "What makes them amateurs?" "Well, they can't be paid." "Why not?" "Because they're amateurs." Who decided they are amateurs? "We did." "Why?" "Because we don't pay them."' “The NCAA assertion that ‘student-athletes’ will not be paid because they are students first and athletes second does not withstand a basic test of logic” (Huma & Staurowsky, 9). Football and basketball players attending schools with big-time sports programs are, according to the NCAA, to be considered an integral part of the student body, yet NCAA regulations force students to shoulder a burden that no other students share (Huma & Staurowsky, 7). Scholarships, for example, were changed from four-year athletic 14 scholarships to one-year renewable scholarships in 1973 (Sack & Staurosky). Thus, because scholarships are now renewable at the discretion of the athletic coaches, the players are essentially voiceless when it comes to their own educational welfare and under great pressure to remain athletically competitive. Subsequently, this pressure leads to a complete and utter disregard of the NCAA’s own “4 and 20” rule by players, coaches and the member schools themselves. This rule restricts a college athlete from dedicating more than 4 hours per day and 20 hours per week to their sport; however, according to data gathered by the NCAA for the 2009-2010 academic year, FBS athletes reported spending 43.4 hours per week on athletic activities in-season and Division 1 men’s basketball players reported spending 39.2 hours per week on athletic activities in-season (Huma & Staurowsky, 8), both approximately double the allotted time. While NCAA coaches may not explicitly impose certain requirements, such as working out during the offseason, the players know that if they don’t, they may not remain competitive and will ultimately risk the renewal of their scholarship. The lead Plaintiff in the trial, former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon, testified in court that he felt like “an athlete masquerading as a student” during his college days (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 39). Between practices, traveling and games, student-athletes playing football at FBS schools and basketball at a Division 1 schools are far from integrated into their academic communities and the NCAA’s current rules do not help to promote academics above athletics. While this problem is not one that the Court was asked to resolve in this case, it undermines the NCAA’s primary stance on why they restrain student-athlete compensation. 15 The Black Market “[T]he NCAA’s version of amateurism is not only at the root of the problem, it is impossible to uphold” (Huma & Staurowsky, 20). Because the athlete’s full “grant-in-aid” scholarship is typically still a few thousand dollars below the actual cost of attendance, which includes things such as transportation and other expenses related to attendance at a specific institution, it is not surprising that scandals involving players receiving money in violation of NCAA restrictions is common. Inside Higher Education reported that 53 of 120 FBS schools were caught violating NCAA rules between 2001 and 2010 (Lederman). The fact that over 44% of FBS schools that have been caught violating NCAA rules in a 10 year span, makes one wonder how many other FBS schools do the same, yet simply haven’t been caught. While these violates do not all involve player’s receiving “illegal” compensation, the increasing number of schools committing NCAA violations is alarming and speaks to the flawed system put in place by the NCAA years ago. In Tim Tebow’s book, Through My Eyes, he discusses how he felt seeing his coach receive a million dollar bonus at a time when the only Christmas present he could afford to give his mother was to pull weeds from her chicken coup. Tebow, known for his “strong personal and moral convictions,” restrained from accepting money from boosters and agents while in college, yet questions the morality of the NCAA and their rules that they impose throughout his book (Huma & Staurowsky, 21). Reflecting a similar opinion regarding the NCAA restrictions, University of Southern California receiver, R. Jay Soward, confirmed to Sports Illustrated a few years ago that he had accepted benefits from a sports agent while in college, as his scholarship didn’t provide enough money for rent or food (Huma & Staurowsky, 20). Through exposed scandals/violations of NCAA rules and the expressed opinions of many current and former 16 college athletes, it has become clear that the evolution of the collegiate sports industry, in combination with the stagnant NCAA restrictions, has created an environment in which popular collegiate athletes can be easily manipulated by financial rewards and incentives that violate NCAA restrictions. Recommendations Decision to Appeal Following the decision of the O’Bannon case, the NCAA filed an appeal with the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. In the appeal the NCAA asserts that Judge Wilken erred by not applying a 1984 Supreme Court ruling that the NCAA believes protects amateurism in college sports (Solomon). The 72 page filing specifically focuses on what the NCAA believes are three flaws in the decision: “Wilken declined to follow the 1984 Oklahoma v. Board of Regents case that ended the NCAA's monopoly on television broadcast. That Supreme Court ruling included language that ‘athletes must not be paid’ and the NCAA argued other district courts have upheld Board of Regents” (Solomon). 2. Antitrust laws don't apply to the challenged rules because they do not regulate “commercial' activity.” Whatever economic consequences these rules may have, their purpose is to define who is eligible to play the sports that NCAA member schools sponsor (Solomon). 3. The O'Bannon Plaintiffs lack antitrust injury. While the players are seeking payments for the rights to use their names, images and likenesses in live TV, archived footage and video games, no state recognizes such a right in telecast of games and other claimed non-commercial uses. Regardless, the First Amendment and the Copyright Act would bar enforcement of any such right (Solomon). 1. The overarching purpose of this proposal, however, is not only to show that the court was correct in the initial decision, but to provide the NCAA with the proper perspective as to why these changes are necessary and beneficial based on the current state of the industry and the evolution of the roles played by those within it. 17 Through the examination of the collegiate sports industry it has become obvious that many regulations enforced by the NCAA have actually undermined their purported mission of preserving the idea of amateurism and the student-athlete. If addressed properly, the injunction issued by Judge Wilken can help to align the NCAA’s vision and mission with the way they treat their athletes and thus, I propose that the NCAA embrace the changes initiated in the decision rather than appeal them. I will next provide two more specific recommendations that I believe will help alleviate this dissonance and promote the coherence of the NCAA’s mission with the imposition of fair compensation deserving of the studentathletes. One-Year vs. Four-Year Scholarship Option As mentioned previously, the four-year scholarship was changed to a one-year renewable scholarship in 1973. This regulation undermined the NCAA’s idea of the collegiate sports player being a student first and an athlete second. Things like poor athletic performance and permanent injury are reasons a coach may choose not to renew an athlete’s scholarship, yet NCAA institutions are free to renew scholarships of players that are academically ineligible, highlighting the fact that athletic scholarships hinge primarily on athletic performance rather than academic performance (Huma & Staurowsky, 7). The oneyear scholarship exerts a tremendous amount of pressure on student-athletes to remain athletically competitive within their respective teams, which in turn causes them to spend excessive amounts of time on sport-related activities. Giving FBS football and Division 1 basketball programs the option of offering four-year athletic scholarships will again promote the NCAA’s dedication to the education of their athletes and can take pressure off the player’s who already shoulder a burden that no other students share. Players wishing to leave 18 college before graduation to turn pro, or for other reasons, will still be permitted to do so under a four-year athletic scholarship. This decision will further promote competition within NCAA member schools, since recruits would then have the benefit of obtaining educational security from the schools offering four-year athletic scholarships. While some may argue that this change will promote laziness and a lack of determination amongst some athletes, I submit that this is not the case. By providing a student-athlete with educational security, he will focus more on improving his athletic abilities rather than on how many hours he is putting in just to ensure his continued scholarship. With this four-year scholarship option, the NCAA will still have the ability to end the scholarship early provided that certain conditions were not met. With a tribunal process, the NCAA would have the ability to bring a studentathletes case before a board/panel to discuss the issue at hand and a decision would be made as to whether or not that student deserves the right to retain their scholarship and/or roster spot. Scholarship Requirement The injunction states that the NCAA will be not be allowed to prohibit member schools and conferences from offering recruits a limited share of revenues generated from the use of their names, images and likenesses in addition to a full grant-in-aid and also states that the NCAA will not be permitted to set this cap below the cost of attendance (Edward O’Bannon v. NCAA, 96). I propose, however, that the NCAA take the ruling a step further and require all athletic scholarships to fully cover the cost of attendance. As explained previously, FBS football players and Division 1 basketball players spend incredible amounts of time on sport-related activities while in season. In fact, student-athletes in both sports spend approximately double the amount of time on sports-related activities than the NCAA 19 allows. As seen in Figure 3, only one country examined in a United Nations study (Mexico), had a higher average work hours per week (43.5 hours/week) than the time FBS football players report spending on sports-related activities while in season (43.4 hours/week). Additionally, student-athletes must also dedicate a significant amount of time to their education. These extreme time commitments severely limit the ability of student-athletes to obtain a means of generating income, as non-athletes can, such as working an off-campus job. An analysis of the out of pocket expenses that the average FBS “full” scholarship athlete faces revealed an average yearly shortfall of $3,222 between full “grant-in-aid” scholarships and the overall cost of attendance (Huma & Staurowsky, 4). The average scholarship shortfall per student-athlete in some of the largest FBS football programs can be seen in Figure 4. It only seems right that the laborers who generate millions of dollars for the NCAA and its member schools are entitled to scholarships that cover the costs of basic school needs, as determined by institutional financial aid offices. This change will help alleviate the persistence of the “black market” present in the college athletics industry, thus reducing the number of NCAA regulations violated by student-athletes and NCAA members schools. Conclusion The truth is, the NCAA has become part of Corporate America. It is no longer simply the educational association it purports to be (McCormick & McCormick). For the longest time the NCAA has used the veil of amateurism as a way to act monopolistically and take advantage of the very athletes that generate their revenue. While the O’Bannon case, in its groundbreaking decision, has clearly changed the face of college athletics moving into the future, it is now up to the NCAA to catch up with the modernization of college sports, 20 embrace the necessary changes and make a positive impact on the collegiate sports industry as a whole. 21 Figures, Data, Tables Figure 1: Recent FBS Revenue Growth Lavigne, Paula. "How Much Colleges Made and Spent on Sports in 2012-2013."ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 1 May 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. Figure 2: Revenue Breakdown for FBS Schools Lavigne, Paula. "How Much Colleges Made and Spent on Sports in 2012-2013."ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 1 May 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. 22 Figure 3: Average Global Working Week by Country (United Nations Study) Wesley, Daniel. "The State of the 40-Hour Workweek." VIsual Economics CreditLoan. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Dec. 2014. Figure 4: Scholarship Shortfall Per FBS School Student-Athlete Huma, Ramogi, and Ellen J. Staurowsky. "The Price of Poverty In Big Time College Sport." (n.d.): n. pag. National College Players Association. National College Players Association, 2012. Web. 16 Dec. 2014. 23 Works Cited "Antitrust." Cornell University Law School. Legal Information Institute, n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2014. Barro, Robert J. "The Best Little Monopoly in America." Businessweek. N.p., 08 Dec. 2002. Web. 16 Dec. 2014. Edward O'Bannon, et al. v. National Collegiate Athletic Association; Electronic Arts Inc.; and Collegiate Licensing Company. United States District Court for the Northern District of California. 8 Aug. 2014. Print. ESPN.com News Services. "Judge Rules Against NCAA." ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 09 Aug. 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2014. Huma, R., & Staurowsky, E. J. (2012). The $6 billion heist: Robbing College Athletes Under the Guise of Amateurism. Huma, Ramogi, and Ellen J. Staurowsky. "The Price of Poverty In Big Time College Sport." (n.d.): n. pag. National College Players Association. National College Players Association, 2012. Web. 16 Dec. 2014. Lederman, D. (2011, February 7). News: Bad apples or more? Inside Higher Education. McCormick, A.C., & McCormick, R. A. (2008, May-June). The Emperor’s New Clothes: Lifting the veil of amateurism. San Diego Law Review 45, 495 McDuling, John. "A Guide to American College Football, the Multibillion-dollar Business Where the Labor Is Free." Quartz. N.p., 13 Sept. 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2014. "Monopoly Definition | Investopedia." Investopedia. N.p., 24 Nov. 2003. Web. 14 Dec. 2014. NCAA Academic and Membership Affairs Staff. "NCAA Division 1 Manual." (2014): 1398.NCAA Publications. NCAA, Oct. 2014. Web. 16 Dec. 2014. Sack, A. L., & Staurowsky, E. J. (1998). College athletes for hire: The evolution and legacy of the NCAA amateur myth. Westport, CT: Praeger Press. "Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890)." Our Documents. General Records of the United States Government, n.d. Web. 13 Dec. 2014. Solomon, Jon. "NCAA Relies Heavily on Supreme Court Case to Appeal Paying Players." CBSSports. CBSSports, 15 Nov. 2014. Web. 17 Dec. 2014. Tebow, T. (2011). Through my eyes. New York: Harper. 24 "Transcript of Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890)." Our Documents. General Records of the United States Government, n.d. Web. 15 Dec. 2014.