Love Between Us - Dayspring Baptist Church

advertisement

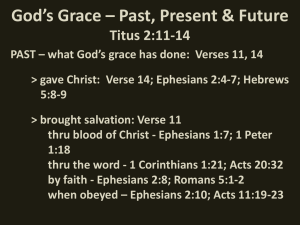

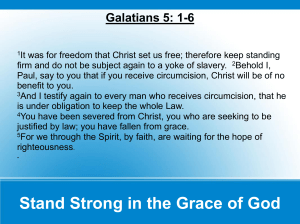

1 A Sermon for DaySpring By Eric Howell “Love Between Us” (1st in a series – It Happens at Church) Ephesians 3:1-12, 20 January 4, 2015 The letter to the Ephesians has been called Paul’s churchiest letter. The word church is used nine times in this short letter, beginning in Chapter 1 where the church is the body of Christ, to Chapter 5 where the church is the bride of Christ. In between, an idea of church emerges; a vision unfolds. The church is here identified and called to be something very special. This was so obvious to St. Paul that the church, to him, was a source of endless fascination and commitment. Not just in Ephesians . . .he wrote about it everywhere. To the Romans, the church was the place where differences weren’t important and all stood equally as forgiven sinners before the Lord. To the Corinthians, church was the place where a common meal was shared and no one should go away hungry. To the Thessalonians, church was the anticipation of Christ returning very soon. To the Galatians, church was where truth must be proclaimed and not shaded by what itching ears want to hear. To the Philippians, church was where God was finishing the good work already begun in each person as they poured out their lives as Christ did. Something very special and important is going on here even if it’s easy to miss. Writing about her own church in particular and all churches too, Frederica Mathewes-Green observes: “A little church on Sunday morning is a negligible thing. It may be the meekest and least conspicuous thing in America. Someone zipping between Baltimore’s airport and the beltway might pass this one, a little stone church drowsing like a hen at the corner of Maple and Camp Meade Road. At dawn all is silent, except for the click every thirty seconds as the oblivious traffic light rotates through its cycle. The building’s bell tower is out of proportion, too large and squat and short to match. Other than that, there’s nothing much to catch the eye. In a few hours heaven will strike earth like lightning on this spot. The worshippers in this little building will be swept into a divine worship that proceeds eternally, grand with seraphim and incense and God enthroned, ‘high and lifted up, and his train filling the temple.’ The foundations of that temple shake with the voice of angels calling ‘Holy’ to each other, and we will be there, lifting fallible voices in the refrain, an outpost of eternity. If this is true, it is the most astonishing thing that will happen in our city today.” She confesses, “I believe this is true. I didn’t always. But I now believe it is the most important thing I will do in my life. When death strips away from me all the shreds of foolishness, self-indulgence, gossip, and greed, this will remain, one of the few things to remain.” 2 If the visit by the wise men to the cradle of Jesus was the seed of the gospel’s manifestation to all the world, the church is its flowering. In Ephesians the word church is used a lot, 9 times. It says almost everything you need to know that the word used most in Ephesians is “one,” (26 times); the second most used word is “love” (19 times); the third is “grace” (12 times). On St. Paul’s mind is one-ness in love and grace. Church is the place where God’s great idea flowers, God’s great mystery is made known: the mystery that church is for everyone and everyone is included in God’s grace. One-ness, love, and grace: these are three legs of the Ephesian vision of the church’s stool; unity, love, and grace. To cynical ears that may sound a little like some kind of squishy everybody-getalong syrupy idea of inclusiveness, far removed from the actual really hard work of being in relationship with other people and far short of the high callings the church ought to be about. A neighborhood association strives to get along. Shouldn’t a church be something more than that . . .something more than unity, love, and grace? Part of the answer to that question is: take it up with Paul. This is his vision. The other part of the answer is yes, it is more than that, and he sees it too. Indeed, the unity forged by love and grace in the church is more than for its own good-feelings. It is a witness to “bring to light the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things, so that through the church the manifold wisdom of God might now be made known. . . “ Whoa. The vision of a church made one of many unified by love and grace is witness to the enduring mystery of God, described as manifold or in other translations: in varied forms, many-splendored, of rich variety. I didn’t know manifold was a Bible term. I thought it was something on a car. In a car, an exhaust manifold is equipment that takes exhaust from several different pipes and brings it together as one. An intake manifold takes fresh air from the outside and distributes it evenly to each of the cylinders in the engine. This is actually a good way to remember what manifold means: it’s the one-of-many whether it is the gathering of the many into one or the distribution of the one into many. Manifold is one and many. Christians, who are used to thinking of God as Trinity--Father, Son, and Holy Spirit--would naturally already understand oneness and unity bound in love. This is who God is and who we are made to be. When the church is a place where all sorts of different people come together and are one, the church is a living, breathing witness to the wisdom of God in all its forms. It’s a witness not only to others here on earth but a witness to the manifold wisdom of God “to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly places.” That exalted language suggests that there is a spiritual realm watching us, helping us, sometimes opposing us, and when the church lives its life as church in the ways 3 God intended, the spiritual realm sits up and takes notice. What we do here matters. There’s a power in the church. What we do here matters. Who we are together matters. At the heart of gospel faith is recognition of a link between the mystery of love and the mystery of God. There’s a huge gap between that infinite love to which we are destined and the love we experience here below, even, or maybe especially, in church where the gap and the link are most obvious. Love is good but hard work if the church is at its core a place from the beginning where differences are loved into unity. It’s hard work. On the day of my ordination to ministry, my mentor and childhood pastor Cecil Sherman came to our small crossroads in North Carolina to preach the service. On that Sunday afternoon we pulled the car into the drive of the church. It was a pretty red brick white steeple church fronted by a half-moon drive, approached by a set of 10-15 steps to the front door, and flanked by sets of gravestones on the left and right sides of the church. Dr. Sherman stepped out of the car and took the scene in. In his famous slow dry wit, he made two quick observations. Noting the fresh flowers and landscaping, he said, “Someone loves this place.” Then noting the two sets of gravestones on either side of the building he said, “Someone didn’t get along with each other.” Being church is hard work. One, love, and grace are the most used words in the churchiest book in the New Testament. The fourth most used word is ‘flesh’. In Bible-speak, flesh is the stuff we have to struggle against, the temptations, the easy ways out, the stuff that divides us, not lifts us up. In St. Paul’s vision, which he believes to be God’s revealed mystery, church doesn’t find its way around those very real matters, it goes right through them, right to the heart of the human condition, where the great diversity of God’s people and God’s wisdom are made one by love and grace overcoming the flesh. It’s who we’re made to be and a work of growing up in the way of Christ. Eugene Peterson puts it this way, “The contrast between world and church in this regard is stark: American culture is doing its dead level best with its celebrities, consumerism, and violence to keep us in a perpetually arrested state of adolescence. Yet all the while the church is quietly and without false advertising immersing us in the conditions of becoming mature to the measure of the full stature of Christ.” (Practicing Resurrection, 146) Peterson earned his stripes in this regard as a church planter in the suburbs. He set out to keep things as simple and straightforward as possible, concentrating on two things that will resonate with DaySpringers: “I would gather and lead a congregation in the worship of God, and I would invite them into a life of community with one another.” (PR135). He thought the worship part would be hard and the community part would be easy, figuring that most of the people with the picket fences, postage stamp backyard pools, and two cars tucked into garages would be secular, irreverent people who 4 wouldn’t know where to begin the practice of entering the mystery of God, but that at least they would welcome a safe place to know and love their neighbors. He got it exactly backward. It wasn’t long before he had people worshipping God on Sunday mornings. They weren’t totally at ease and had to learn a new vocabulary for mystery and for things you can’t go to the shopping mall and buy, but there they were on Sunday morning. “But getting them interested in each other was another thing entirely. (135) They didn’t want neighbors. They wanted to be self-sufficient, independent.” He says that attending a contentious meeting of the neighborhood association about six months after the church began was sobering. “From that moment I was faced with the complex difficulties of gathering a congregation of warring factions into a place where the wall of hostility had been broken down and a church was being built on its site.” Many of the people at that rude, harsh meeting became members of his congregation. Some took a long time to embrace their neighbors in community. Peterson remembers, “One man, Reuben, the most vituperative in that early community meeting, never did submit. Twenty-seven years later I conducted his funeral in the church he had sat in every Sunday, as angry and sullen as the night I first met him.” Sure church is hard if we’re really going to do it, but it’s also the most important, most interesting, most exciting, most hopeful thing on earth. In all its forms, in every place, from the overlooked side of the highway, to the suburbs of a northern city, to an ancient European cathedral with its gilded ceiling, bells and incense, to a small town Texas main street Baptist church with its “Just as I Am” altar call, to here in this place, when the church gathers . . . it’s the most astonishing thing that happens in the world. For all the Reubens and all the sinners and all the saints who love and learn to love in the name of Jesus Christ, what we do matters on earth as it does in heaven. It’s where heaven’s lighting strikes the earth. The language of Ephesians—of church--is not the engineered world of manifolds of bent steel and forced air, but the language of prayer, which is the natural tongue of the church. It is no wonder then that this high, just-almost unreachable vision cast before us is followed by a prayer of blessing for the people drawn into the work of being reshaped by this vision. It is a prayer for the ages and for us in this new year: I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named, that according to the riches of his glory he may grant you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith—that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge that you may be filled with all the fullness of God. 5 Now to him who is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think, according to the power at work within us, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, forever and ever. Amen. Copyright by Eric Howell, 2015