action research (Autosaved)

advertisement

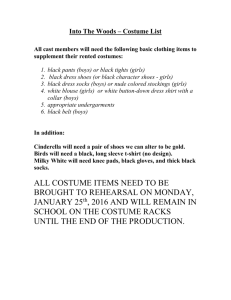

BROOKLYN COLLEGE Does Gender Matter in Teaching? Trisha- Ann Matthew-Cadore Education 7202T Fall 2010 Professor Dr. Sharon O’Connor-Petruso 2 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction …………………………………………………………….……...4 Statement of the Problem .………………………………………………4 Review of Related Literature .…………………………………………..5-14 Statement of the Hypothesis.…………………………………………….14 Method Participants ...……………………………………………………………14 Instruments ...……………………………………………………………14 Experimental Design ……………………………………………………15 Procedure ………………………………………………………………..16-17 Results ……………………………………………………………………….......17-21 Discussion.……………………………………………………………..…21-22 Implications ……………………………………………………………....22 References……………...…………………………………………………23-25 Appendices: Appendix A --- Consent Form ………………………………………..………26 Appendix B --- Parent Consent Form …………………………………………27 Appendix C --- Demographic Survey …………………………………………28 Appendix D --- Pre-Survey…………………………………………………….29 Appendix E --- Post-Survey……………….……………………………………30 3 Abstract This action research project analyzed the relationship between homogenous grouping and boys’ achievement in literacy. The study focused on literacy boys literacy scores in heterogeneous groups were compared to literacy scores in homogenous groups. The action research project took place in P.S. X a Title 1 School in Brooklyn New York from September 2010 through December 2010. 4 Introduction The underachievement of boys has been a popular topic for quite some time now. However, in last few decades there has been an increase in the attention paid to problem of boy’s achievement. Underachievement is concerned with potential not lack of ability, while high and low achievement are concerned with performance. There have been many explanations suggested by researchers as to why boys are achieving less at school. Although, many of the researchers have agreed that there is a problem, no one has truly arrived at the solution to this problem. Kaufman (n.d.) believes separating boys and girls from each other will help boys learn better. Rivers & Barnett (2008) believes that separating the genders is not only discriminating but that it doesn’t work. There are those who believe the problem is the teachers and parents expectations of the boys. They believe boys aren’t doing very well because we don’t expect them to. Some researchers believe teachers need to change their teaching styles to suit the needs of the boys in the classrooms. They believe if we change our traditional teaching and adapt different methods the boys will learn better. With all the research available the problem still remains. Should boys and girls be taught differently? Does gender matter in teaching? Statement of the Problem A great amount of elementary boys are academically lagging way behind the girls. “Boys need to play an active role in the learning process or else their lose interest” (Hodgetts, 2008, p. 468). This research will attempt to answer the questions: Does gender matters in teaching? Do boys and girls learn differently and as a result should be taught differently? 5 Review of Literature As boys’ behavior and performance in school continues to decline researchers are trying to come up with an explanation for why this is happening. Michael Gurian of the Gurian Institute believes, “Schools are run counter to how boys learn and how their brains operate. The language of girls’ brains develop earlier, so reading and writing comes easier to them, while boys’ brains are better at spatial-mechanical tasks and males learn better when they are active” (Delisio, 2006). Dr. Leonard Sax, bestselling author and executive director of the National Assn. for Single Sex Public Education, would agree with the above mention researchers. Dr. Sax believes that they are innate characteristics that boys and girls possess that explain why they aren’t performing at close to the same level. He says, “Girls are born with a sense of hearing significantly more sensitive than boys’, particularly at the higher frequencies most important for speech discrimination. Those differences grow larger as kids get older” (Sax, 2006, p. 191). “If you turn up the heat, the boys go to sleep, they get sluggish and their eyelids get heavy. If you keep it just a little chilly, the boys learn better” (p. 193). These principals was using the finders of ergonomics specialists, who found that the ideal ambient temperature for young men is about 71⁰ F, versus 77⁰ four young women. Coates and Drave will agree with Dr. Sax’s in that the reason why boys get worse grades than girls is because boys have different biological and neurological characteristics than girls. They also offer a different explanation for the gender gap in learning, “Boys learn differently than girls, and today’s boys also learn differently than previous generations of students. Boys are actually ahead because of neurology, boys are actually ahead in leading society into the new economic age of the 21st century. Boys are 6 punished for homework and grades are lower because of behavior unrelated to learning and knowledge. Smart boys turn in homework late, and this is also explained by the boy’s hard wiring” (Coates & Draves, 2006, p.6). Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences (1983) tells us that students learn differently, and as teachers we have to embrace the several different intelligences in order to ensure that we are meeting the needs of all the students in our classrooms. Dunn agrees we all learn differently. She writes, “Students are not failing because of the curriculum. Students can learn almost any subject matter when they are taught with methods and approaches responsive to their learning style strengths” (Dunn, 1990, p. 15). According to Beaman, Wheldall and Kemp (2006) and Gilliam (2005) gender is a child characteristic with significant implications for development. Gender helps create a set of environmental expectations and transactions unique to boys or girls, and there are gender differences in behavior as well that due to gender socialization practices, including differential adult expectations, girls tend to fit more naturally into the student role than do boys. Girls may find it easier than boys to sit for long periods of time and complete projects requiring fine motor skills. Teachers pay more attention both positively and negatively to boys than to girls, which appears to be largely related to boys’ comparatively more exuberant and disruptive classroom behavior (Cameron, Kaufman & Brock, 2009, p.143). Cohen (1998) believes “boys’ underachievement has routinely been explained away, the failure of males students taken as evidence that educational practices need to be simply improved. She argues that this pattern has not served boys well, working as it has to preclude meaningful interrogation of the relationship between masculinity and 7 successful engagement with school” (Hodgetts, 2008, p.467). Educators know that boys aren’t performing as well as the girls; however the blame is on the curriculum only. It is hardly taken into account that boys and girls are different and therefore need to be taught differently. “For example boys need to play an active role in the learning process or else their loose interest. Through binary representations, this repertoire served to position boys as inherently oriented to learning through action and involvement, rather than through traditional academic tasks such as reading, listening and copying” ( 2008, p.468). Boys are usually not interested in literature in the context of the way our classrooms are set up. This model however works well for girls because girls are passive. Girls can be told after you are finished, work with something quietly at your seats. Boys, no, instead the activity should be a cooperative activity, an activity in which they are allowed to work together with other students and are actively engaged. Hodgetts (2007) offers another explanation for why boys are achieving less. She believes that it might be because boys are resistant to the curriculum that is being taught, whereas the girls are compliant. “This dichotomy served to establish the value of boys’ learning style and outcome knowledge, a result of their resistance to the meaningless tasks to which girls passively ‘submit’. Lingard and Mills (2009) found that the reasons boys aren’t doing well is because there aren’t enough male role models in their lives. This study took into account that many boys do not have role models at home or in their classrooms. Karlsson a principal in a southern rural school in Iceland claimed, “That there is a danger ahead for boys because many do not see men in their homes, their early childhood schools, ore even their 8 primary schools” (Lingard & Mills, 2009, p. 317). He also says that schools have been feminized and this has left negative implications for the wellbeing of boys. Behling, Courtis and Foster (1982) concluded that, regarding learning, the most effective teacher-pupil combination is female-female and the least effective is a female instructor and a male pupil (Klein, 2004, p. 185). Carrington, Tymms and Merrell (2006) disagree with that study and find the opposite. Their research, “found no empirical evidence to support the claim that there is a tendency for male teachers to enhance the educational performance of girls. Of particular note is the finding that children taught by women-both boys and girls alike-were more inclined to show positive attitudes towards school than their peers taught by men” (Tymms & Merrell, Carrington, 2006, p. 317). According to Hall (2001) there is a gender relationship between educational expectations of urban, low-income African American youth, their parents, and their teachers. African Americans males are performing much lower than African American girls. Twice as many girls than boys are graduating from high school and college. African American males are often perceived as possessing characteristics that are incongruent with academic success (e.g., laziness, propensity toward violence, valuing athletic over academic accomplishments). Research suggests that African American youth have internalized this view of African American males. Reese (2004) “black boys” deliberately do poorly in schools because they have been called sissies and other names by their black classmates (Wiens, 2006, p.17). Harris (1995) agrees with Woods and states, “Boys in poor and working-class populations are at an immediate disadvantage in school. Black boys are at an even greater disadvantage. Many black males in our society embrace the notion that they are victims, that racism, The Man, treacherous black women, bitches of 9 all colors and so forth are all making it hard for them to get ahead” (Wiens, 2006, p. 17). According to Extrom (1994) a teacher’s stereotypical gender perceptions are also expressed in differential expectations concerning behavior. Girls are perceived as betterbehaved, which gives them an advantage when teachers evaluate their achievement. (Klein, 2004, p.185). Freeman (2004) Data from Early Childhood Longitudinal Study indicate that, on entering kindergarten, boys and girls perform similarly on tests of general knowledge, reading and mathematics. However by the spring of the 3rd grade, boys have slightly higher mathematics scores and lower reading scores. The subject-specific gender gaps appear to expand as students advance through the elementary and secondary grades. Other different educational outcomes for boys and girls are boys are substantially more likely than girls to repeat a grade (Thomas, 2006, p. 531). According to Jacob (2002) Boys are now increasingly less likely to than girls to attend college and to persist in attaining a degree (Thomas, p. 531). Conlin (2003) Upon entering kindergarten, the average boy is two years behind the average girl in both reading and writing. Boys account for 65% of infants and toddlers receiving early intervention services for developmental delays. Zill, Collins, West and Hausken (1995). “In fact, in the United States, special education classes contain three times as many boys as girls and boys are four times as likely to be diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Boys account for 71% of all school suspensions and ninety percent of all disciplinary actions and infractions” (Wiens, 2006, p.12). This research by Ringrose (2007) examines whether there is ever going to be equality among the gender. According to Cohen (1998) boys have not changed: they have 10 always underachieved, but it has never been addressed. She suggest the question is not ‘why are boys underachieving?’ but ‘why are we concerned about it now?’ Boys’ underachievement, she argues, is not the result of changes in the work force, or of changes in the performance and self-esteem of girls. Boy’s underachievement has historically been protected from public scrutiny by the sustaining of the myth of boys intrinsic potential and this has not served them well (Jones and Myhill, 2004, pg. 533). According to Osler, Street, Lall and Vincent (2002) Crudas and Haddock (2005) “The most ironic, disturbing effect of the current post-feminist, neoliberal gender equity discourses in educational policy is the steady stream of resources focused on boys supposed underachievement and needs at every level of the educational agenda, which has now resulted in a massive neglect of girls in terms of resource allocation and policy and research concerns (Ringrose, 2007, p.473) According to van Langen and Dekkers (2005), the topic is typically not considered in sufficient detail and the conclusion should rather be that boys perform better than girls with regard to some aspects of education (e.g.. math and science subjects) while girls perform better than boys with regard to other aspects (e.g.; language, behavior). It also appears that the phase in school careers of pupils should be considered as well as the country in question as major differences have been found to occur along these lines (Dreissen, 2007, pg.185). The study conducted by Hoing (2008) agrees with Driessen. Hoing states, “It has been a consistent finding in the literature that girls generally receive better grades than boys. However, results look different when focusing on standardized achievement test scores. Evidence from a meta-analysis and large-scale 11 assessments supports the notion of a slight advantage for males with respect to math achievement test scores in later youth an adult age”(Hoing, 2008). There are many schools that are trying to address the pressing issue of underachieving boys. In Los Angeles, California Campbell Hall a private coed school, 12-year old student Brett Landsberger believes this about his school being separated by gender, “We can express ourselves better”(Rivera, 2006). Newquist (1997) Educators in California believe that schools should be single-gender. Girls are characterized as being more collaborative in the classroom; boys are said to be more competitive. Does this mean schools should offer single-gender schooling? The answer for California education is a resounding yes. In Columbia, South Carolina second-grade teachers Garneau & Gamble are convinced that segregating elementary-age boys and girls produces immediate academic improvement-in both genders (Kaufman, n.d.). The two consulted David Chadwell, South Carolina’s coordinator of single gender education. According to Chadwell, “We can teach boys and girls based on what we now know because of medical technology” (n.d.). Chadwell believes that boys and girls see differently, he states, “Male and female eyes are not organized in the same way, he explains. The composition of the male eye makes it attuned to motion and direction. Boys interpret the world as objects in space. The teacher should move around the classroom.” (Kaufman, n.d.) Knowing this about the gender should therefore help us to educate them better and David Chadwell believes that in a single gender classroom learning can be maximized. Sax (2006) “For single-sex format to lead to improvements in academic performance, teachers must understand the hard-wired differences in how girls and boys 12 learn. In particular, teachers need to understand the importance of differences in how girls and boys hear, see, and respond to different learning styles” (Sax, 2006, p. 195) Dunn, Griggs, Olson, Gorman, and Beasley (1995) agree that students learn differently and agree that when teachers teach to the students’ learning styles students achieve more. A meta-analysis of forty-two experimental studies conducted with the Dunn & Dunn Model between 1980 and 1990 by thirteen different institutions revealed that students whose characteristics were accommodated by educational interventions responsive to their learning styles could be expected to achieve 75 percent of a standard deviation higher than students whose styles were not accommodated (Shaughnessy, 1998). Douglass Elementary School in Boulder, Colorado the boys had both behavior and performance problems. The educators at Douglass decided to do something about their failing boys, “By introducing more boy-friendly teaching strategies in the classroom, the school was able to close the gender gap in just one year. At the same time, girls’ reading and writing performance improved” (Gurian & King, 2006, p.56). Professor Schlosser an economist from the Eitan Berglas School of Economics at Tel Aviv University does not agree. In fact she says “Being with more girls is good for everybody. She found that both boys and girls do better when there are more girls in the class (Science Daily, 2008). Rivers and Barnett (2006) agree with Professor Schlosser and found that although single-sex classes are trendy, there’s scant evidence that they improve academic achievement. Rivers consulted top researcher in the area of sensory perception in early childhood, Dr. Rachael Keen of the University of Massachusetts, she states, “I cannot point to any definite article in a peer-reviewed journal that supports 13 major differences in gender for audition and vision infancy and early childhood” (Rivers & Barnett, 2006). The study conducted by Judith Mulholland and Kaminski (2004) found, “No significant difference in mathematics achievement that can be attributed to gender or class composition. However, scores in school-based English improved for students in single-gender classes. Improvement for girls in single-gender classes was greater than that for boys in single-gender classes” (Mulholland & Kaminski, 2004, p. 31). There are many causes to the problem of boys’ underachievement. “Some theorists believe nurture has the biggest effect on the behavior and academic achievements of boys, others suppose the effects of nature explain the gender gap most accurately” (Wiens, 2006, p. 14). According to Salomone (2003) nature and nurture…reinforce each other in a continuous cycle” (Weins, 2006, p.14). Kurtz (2005) gives a gloom reality into closing the achievement gap between boys and girls. According to work by psychoanalytic sociologist Nancy Chodorow, a women’s studies pioneer, the differences in the sexes simply derive from the contingent circumstance that women happen to be primary caretakers of children. The special “feminine” empathy required for rearing children, she suggests, become associated in our minds with people who just physically happen to be female. Identifying with their daughters, moreover, mothers tend to stay tightly connected with them for years, drawing them into a circle of mutual dependence and empathy that is the essence of femininity” (Kurtz, 2005). Chodorow believes traditionally mothers…tend to encourage their sons to be independent. If they want to be men, boys learn, they’ve got to overcome the qualities of emotional empathy 14 of people like mom. Masculinity thus finds its ground in a rejection of “feminine” equalities (Kurtz, 2005). Statement of Hypothesis HR1: Homogeneously grouping 21 fourth grade students at P.S. X in Brooklyn NY over a four week period will improve their engagement and literacy tests scores. Method Participant The students selected for this action research attend fourth grade in P.S. X in Brooklyn New York. P.S. X is a Title One school in Brooklyn New York. The action research began with 25 students but ended with 21. There was a transfer of students of two boys and two girls into other fourth grade classes in order to even out the numbers. The independent variable use was a change in seating arrangement for boys during literacy instruction. Instead of seating at their seats or with girls boys work in homogenous groups during literacy. Instruments The action research took place from September 2010 through December 2010. Students were administered two tests (pretest and posttest) using the GPS system. Students received the treatment (homogenous groups) for a period of four weeks. Lastly, two surveys one pre and one post. 15 Experimental Design The researcher used the pre-experimental design involving one group. The group is randomly assigned. The single group is pre-tested (O), exposed to a treatment (X), then post-tested. The symbolic design is as follows: OXO The threats to internal validity were history, maturation, testing, instrumentation, selection, mortality and selection-maturation. History was a valid threat because of the many factors that beyond the researcher’s control that affected the results. Such as student absences, weather conditions, classroom interruptions, family conflicts, all affected the results of the action research. Maturation students will be of mixed age and off course different maturity levels. Testing students will not take a pre-test and a post-test for all tests. This will definitely affect the data.The instruments will be valid because its tests that are used by the city. There are threats to validity concerning the surveys because students might not be completely honest when answering the surveys. Selection the researcher is choosing the students who will participate in the survey. Mortality students may be discharge from the school for a number of reasons. This can threaten the data. The researcher believes the external threats are as follows: participant effects, ecological validity, generalizable conditions, multiple treatment and selection. Participant effects, this can be a threat because the researcher does not know the 16 students yet. As the researcher gets to know them and their personalities, then students who bring certain types of behavior to the action research will be discovered. Ecological validity the researcher will be changing the students grouping. Boys seat together for a four week period, which is different from what they are used to. This can be a threat. Generalizable the researcher does not think the action research can be replicated with the same results. This can be a threat. Pre-test treatment students may act differently due to being given a pre-test. This is a threat. Selection-treatment interaction the researcher is doing the selection. Permission is being granted from the principal and parents. Lastly multiple treatment, this is a threat because the participant are being given two surveys with similar questions. Procedure The action research took place over a 4 week period. Students took two surveys. These surveys questioned the students’ feelings towards literacy and seating with boys or with girls. There was a pre survey and a post survey. The pre-survey see (appendix C) was administered in October 2010. The survey was analyzed to see students’ preferences, students were then placed into groups (heterogeneous/homogeneous) according to their survey responses. Students were given a post-test and post-survey in November 2010. The data was analyzed for correlation. 17 The independent variable that was used is students were grouped homogenously during the literacy block for a four week period. For the remainder of the day students received instruction in heterogeneous groups. Results Students were instructed and assessed using the GPS reading system. Upon reviewing the data on whether there was an increase in boys’ literacy scores, after they were placed into homogenous groups during literacy, the researcher didn’t find any correlation. There was no significant difference between the posttest result and the pretest results. In fact the researcher found some of the literacy test scores decreased. Students completed two surveys in which they answered questions concerning their attitudes towards literacy and working with girls or with boys. The researcher collected and analyzed the results of the data observing the correlation between which gender boys work with and their test scores. The survey sentence was, “I prefer working with boys during literacy.” The students responded by selecting a number from one through four on a Likert scale. 18 Students Tests Percentages Group 1-Boys Pre & Post-test Scores 100% 50% Pre-test 0% Student 16 Student 14 Post-test Student 12 Student 5 Student 3 Students Students Test Percentages Group 2 Boys Pre & Post-test Scores 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% Pre-test Student 9Student 8 Post-test Student 2 Student 18 Students Student 15 Student 11 19 Students Test Percentages Group 3 Girls Pre & Post-test Scores 100% 50% Pre-test 0% Student 4 Post-test Student 6 Student 10 Student 13 Student 20 Students Students Test Percentages Group 4-Girls Pre & Post-test Scores 80% 60% 40% 20% Pre-test 0% Post-test Student 7 Student 17 Student 21 Student 19 Students Student 1 20 Grousps Averages Groups Pre & Post-test Averages 80% 60% 40% 20% Pre-test Post-test 0% 1-Boys 2-Boys 3-Girls 4-Girls Groups Pre-Survey Correlation Pre-Survey statement #1: I prefer working with boys only during literacy. Post-Survey statement #1: I can get my work done when I work with boys only during literacy. 1 2 Strongly Agree 3 4 Agree Disagree Strongly Disagree Students Likert Score Pretest Score Likert Score Post-test Students 2 Student 3 Student 5 Student 8 Student 9 Student 11 Student 12 Student 14 Student 15 Student 16 Student 18 2 2 2 1 1 2 2 2 3 1 4 25% 84% 80% 32% 43% 77% 70% 41% 64% 66% 43% 2 69% 62% 85% 23% 69% 85% 85% 46% 62% 62% 23% 4 2 1 1 1 2 3 2 4 21 Correlation between Homogenous Grouping and Student Test Scores 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% Series1 30% Linear (Series1) 20% 10% 0% 0 1 2 3 4 5 Likert Scale Rating -0.34481 There is a negative correlation between homogenous grouping and student test scores. Discussions There is a big debate over how to bridge the gap between girls and boys academic achievement. Numerous theories have been researched and implemented, however not much has been successful in narrowing the achievement gap. Some experts like Rita Dunn believe all students can learn including boys if teachers teach to their learning styles. There others theorists who agree with Rita Dunn such as Michael Gurian who believes,“By introducing more boy-friendly teaching strategies in the classroom, the school was able to close the gender gap in just one year. At the same time, girls’ reading and writing performance improved”. (Gurian & King, 2006, p.56). The researcher didn’t find any significant improvement between boys learning styles and achievement. Boys were given a choice to either work in homogenous groups or heterogeneous groups. Boys first received literacy instruction in heterogeneous groups; 22 they were then pretested, given a survey to find out their seating preference for literacy. They were then placed in homogeneous groups instructed in literacy, post-tested and surveyed one last time. The treatment of homogenous groups took place over four weeks during literacy. The researcher used the GPS reading system, one pre-test and one posttest. The researcher analyzed boys groups pre-test and post-test averages. Implications There are many approaches to closing the achievement gap between boys and girls. The researcher tried instructing boys in homogeneous groups, this was according to their survey preferences. Although each boy given the treatment literacy score didn’t increase there was improvement in the average for each group. The first boy’s group experienced and increase, from a pretest average of 64% to a posttest average of 68%. There was also an increase in the second boy’s group from a 47% pretest average to 55% post-test average. One of the girl’s groups also saw an increase in their post-test average, which went from a pre-test score of 79% to 80%. The second girls group saw a slight decrease from a 62% to 60%. Although there was an increase in the boy’s group overall average, the researcher will not recommend boys seating in homogenous groups for literacy instruction for the entire year. There might have been other factors that can account for the increase in boy’s test scores averages that the researcher did not examine. Longer research should be conducted before recommended homogenous grouping as a method for closing the gender gap in academic achievement. 23 References Beaman, R., Wheldall, K., & Kemp, C. (2006). Differential teacher attention to boys and girls in the classroom. In Cameron, C., Ponitz, S E., Rimm-Kaufman & Laura L.Brock. (2009). Early adjustment, gender differences, and classroom organizational climate in first grade. The Elementary School Journal, 110(58, 339). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ863499). Behling, J., Courtis, C. & Foster, S. (1982). Impact of sex role combinations on student performance in field instruction, Journal of Education for Social Work, 18(2), (9397).Joseph, K. (2004). Who is most responsible for gender differences in scholastic achievements: Pupils or Teachers? Educational Research, 46(2). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ68629). Carrington, B., Tymms, P & Merrell, C. (2008). Role models, school improvement and the ‘gender gap’-do men bring out the best in boys and women the girls? British Educational Research Journal, 34(3), 315-327. (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ799509). Coates, J., Draves., & William, A (2006). Smart boys; bad grades. Retrieved February 2010 from http://www.smartboysbadgrades.com Cohen, M. (1998). ‘A Habit of Healthy Idleness’: Boys’ Underachievement in Historical Perspective. In Hodgetts, K. (2007). Underperformance or ‘getting it right’? Constructions of gender and achievement in the Australian inquiry into boys’ education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(5), 19-34. (Eric Document Reproduction EJ810456). Cohen, M. (1998). ‘A habit of healthy idleness’: boys’ underachievement in historical Perspective. In Jones, S & Myhill, D. (2004). Seeing Things Differently: Teachers Constructions of Underachievement. Gender and Education, 16(4). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ680768). Conlin, M. (2003). The new gender gap. Business Week, 3834. In Wiens, K. The new gender gap: What went wrong? The Journal of Education, 186(3). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ750050) Crudas, L. & Haddock, L. (2005). Engaging girls in voices: learning as social practice. In Ringros, J. (2007). Successful girls? Complicating post-feminist, neoliberal Discourses of educational achievement and gender equality. Gender and Eduacation, 19(4). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ77221). Delisio, E.R. (2006). Helping Boys Learn. Education World. Retrieved February 2010 from http://www.educationworld.com/a_issues/chat/chat170.shtml Dunn, R. (1990). Rita Dunn answers questions on learning styles. How valid is the research on learning styles? Is it really necessary for teachers to diagnose styles and match instruction to individual differences? : Educational Leadership. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. EJ416423). Dunn, R., S. A. Griggs, J. Olson, B. Gorman, and M. Beasley (1995). In Shaughnessy, M. F. (1998). An interview with Rita Dunn about learning styles. Clearing House, (pp.353-61).( Eric Document Reproduction). Extrom, R.B. (1994). Gender differences in high school grades: an explanatory study. In Joseph, K. (2004). Who is most responsible for gender differences in scholastic 24 Achievements: Pupils or Teachers? Educational Research, 46(2). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ68629). Freeman, Catherine E. (2004). Trends in Educational Equity of Girls and Women: 2004. In Dee, T.S (2006). Teachers and the gender gaps in student achievement. The Journal of Human Resources, XL11(3). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ767485). Harris, I.M. (1995). Messages men hear: Constructing masculinities. In Wiens, K. The New Gender Gap: What Went Wrong? The Journal of Education. 186(3). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ750050). Jacob, Brian A. (2002). “Where the boys aren’t: noncognitive skills, Returns to school and the gender gap in higher education. In Dee, T.S (2006). Teachers and the gender gaps in student achievement. The Journal of Human Resources, XL11(3). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ767485). Kaufmann, C. (n.d.) How boys and girls learn differently. Readers Digest. Retrieved February 2010, from http://www.rd.com/make-it-matter-make-a-difference/howboys-and-girls-learn-differently/article103575.html King, K. & Gurian, M. (2006). Teaching to the minds of boys: Is something wrong with the way we're teaching boys? One elementary school thought so and decided to implement boy-friendly strategies that produced remarkable results. http://web.ebscohost.com Kuhn, J.T. & Hoing, H. (2008). Gender, reasoning ability, and scholastic Achievement a multilevel mediation analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(2), 229-233. Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ83561. Kurtz, S. (2005). Can we make boys and girls alike? City Journal .Retrieved February, 2010, from http://www.city-journal.org/printable.php?id=1789 . Lingard, B & Mills, M. (2009). Possibilities in the boy turn: Comparative lesson from Australia and Iceland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 53(4), 309-325. Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ858005. And calls for a more equal policies in dealing with educating the genders. Mulholland, J.H & Kaminski, E. (2004). Do single-gender classrooms in coeducational settings address boys' Underachievement http://web.ebscohost.com Myhill, D. & Jones, S. (2006). ‘She doesn’t shout at no girls’: pupils’ perceptions of gender equity in the classroom http://web.ebscohost.com Newquist, C. (1997).The yin and yang of learning educators seek solutions in singlesex education. Education World. Retrieved February 2010, from http://www.education-world.com/a_curr/curr024.shtml Osler, A., Street, C., Lall, M. &Vincent, C. (2002). In Ringrose, J. (2007). Successful girls? Complicating post-feminist, neoliberal discourses of educational achievement and gender equality. Gender and Education, 19(4), 471-489. (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ771221). Reese, R. (2004). American paradox: Young black men. Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press. In Wiens, K. The new gender gap: What went wrong? The Journal of Education. 186(3). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ750050) Rivera, C (2006). Single-sex classes on a forward course: More schools in L.A. and across the nation separate boys and girls. New federal guidelines extend the leeway. http://articles.latimes.com/2006/nov/20/local/me-singlesex20 25 Rivers, C & Barnett,R.C. (2006). Caryl rivers we can learn together: Singlesex Classes are trendy, but there’s scant evidence that they improve academic Achievement http://articles.latimes.com/2006/oct/02/opinion/oerivers2 Salamone, R.C. (2003). Why gender matters, New York; Doubleday. In Wiens, K. The new gender gap: What went wrong? The Journal of Education. 186(3). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ750050) Sax, L (2006). Six degrees of separation: What teachers need to know about the emerging science of sex differences. Retrieved March 15, 2010 from http://www.boysadrift.com/ed_horizons.pdf Tel Aviv University (2008). Keep boys and girls together in classrooms to optimize learning. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 2010, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/re leases/2008/04/080411150856.htm van Langen and Dekkers (2005). In Driessen, G. The feminization of primary education: Effects of teachers’ sex on pupil achievement, attitudes and behavior. Review of Education 53(2), (329-350). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ784929). Wood, D., Kaplan, R & McLoyd, V. (2006). Gender differences in the educational expectations of urban, low-income African-American youth: The role of parents and school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(4), 417-427. (Eric Document Reproduction EJ762172). Zill, N., Collins, M., West J., and Hausken, E. (1995). In Wiens, K. The new gender gap: What went wrong? The Journal of Education. 186(3). (Eric Document Reproduction Service No. EJ750050). 26 Appendix A Appendices September, 2010 Dear Mrs. Colon, I am writing my Thesis which will be on why boys and girls learn differently, and I need permission from you to conduct surveys, use questionnaires and any other forms of information I might need to satisfy the requirements for my Thesis. Enclosed please find the letter I will send to the parents in regard to this matter. Students will not know they are part of the action research since I will try to incorporate all the information I need during the lessons I teach. Sincerely, Trisha-Ann Matthew Permission granted: 27 Appendix B Parent Consent Dear Parents/Guardians: I am a graduate level student at Brooklyn College and I am conducting and action research project. My action project requires me to observe and gather information from my students. My action research project will be on why boys and girls learn differently. I would like your consent to have your child involved in my action research project. No names or grades are used everything is anonymous. I will be using surveys achievement measurements. Again everything is anonymous. The action research will take place over the course of this school year. Thanking you in advance for your cooperation. Please return the bottom portion to. Sincerely, Mrs. Matthew-Cadore ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ I give my consent for my child to participate in the study: Signed__________________________________________________________________ 28 Appendix C Demographics Survey Directions: Put a check next to all that applies. Gender: ____ Female ____ Male Age: ____ 8 yrs old ____ 9 years old ___ 10yrs old ____ 11 yrs old Race: ___ black/African-American ____Caucasian ____Asian ____Caribbean ____Other ___ Hispanic 29 Appendix D Student Pre-Survey 1 Strongly Agree 2 3 Agree Disagree 4 Strongly Disagree Directions: Rate the following questions (1-4). Choose only 1 answer for each question. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. I prefer working with boys during literacy. I prefer working with girls only during literacy. I prefer working with both boys and girls during literacy. Teachers call on boys more. Teachers call on girls more. Teachers compliment boys more often. Teachers compliment girls more often. I prefer working in small groups during literacy. I prefer remaining at my seat and working independently during literacy. 30 Appendix E Student Post-Survey 1 Strongly Agree 2 3 Agree Disagree 4 Strongly Disagree Rate the following questions (1-4). Choose only (1) answer for each question. 1. I can get my work done when I work with boys only during literacy. ___________ 2. I can get my work done when I work with girls only during literacy. ___________ 3. I can get my work done when I work with both boys and girls during literacy. ______ 4. Teachers complete boys more often. __________ 5. Teachers complete girls more often. ___________ 6. Teachers call on boys more often. ___________ 7. Teachers call on girls more often. ___________ 8. I prefer to work in small groups during literacy. __________ 9. I prefer to remain at my seat and work independently during literacy. ___________