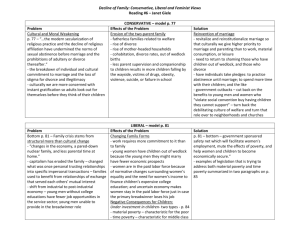

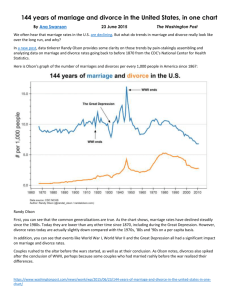

- LSA

advertisement