GBRMPA Reports of interest

advertisement

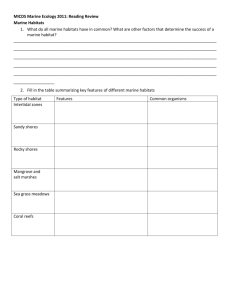

GBRMPA Reports of interest. Why are microalgae important? Marine plants, including mangroves, seagrass, samphires, saltcouch and saltmarsh plants, algae and other plants growing adjacent to the tidal zone, are specifically protected under the Queensland Fisheries Act 1994. The Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries (DPI&F) recognises that this broad definition includes a diverse group of microalgae found within sediments of fish habitats such as mudflats, sandflats, salt marshes, tidal marshes and estuaries. Microalgae are extremely important for primary production within intertidal habitats and constitute a major food source for higher trophic levels. A number of activities such as dredging and extractive industries may impact on fish habitats and microalgae populations and the impacts could lead to reduced local and regional fisheries production. Although algae are included in the definition of marine plants, there are practical difficulties in their identification and estimates of abundance. Where there is readily available evidence of algae, DPI&F will be a concurrence agency and exercise its ability to require an approval for disturbance of these (Couchman and Beumer 2007). The results of a literature review (undertaken in 2002) on the available information on the importance of microalgae in primary production within intertidal fish habitats is summarised below. Fish habitat is defined in the Fisheries Act 1994, “Includes land, waters and plants associated with the life cycle of fish, and includes land and waters not presently occupied by fisheries resources”. This definition captures the habitats occupied by microalgae. What are microalgae? “Microalgae are unicellular microscopic algae called phytoplankton (‘phyto’= plant; ‘planktos’= made to wander). These small plants range in size form 1/1000 of a mm to 2mm floating in the upper 200m of the ocean where sunlight is available for photosynthesis. Phytoplankton species range from primitive blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) to diatoms, dinoflagellates and green flagellates” Hallegraef (1991). Saltmarshes Saltmarsh habitats cover 1660 km2 of the Great Barrier Reef coast, and generally occur on the landward side of mangroves. Saltmarshes tend to occupy the hyper-saline|| soils of the upper inter-tidal zone, where saltwater inundation occurs less frequently (usually only during high spring tides). These communities are generally found growing on the landward side of mangroves, and are made up of salt tolerant, flowering plants in the form of low growing shrubs, herbs and grasses.2 The areas of bare ground found in and around saltmarsh habitats are known as ‘saltpans’ or ‘saltflats’, and are covered in mats of algae during the wet season. Throughout this chapter, saltpan habitats are included within saltmarshes. Saltmarsh communities occur in both tropical and temperate regions of Australia, with higher species diversity found in temperate regions. For example, there are approximately 26 saltmarsh species along the GBR coast51 compared to approximately 50 saltmarsh species in temperate regions of Australia.10 The coastal areas in and adjacent to the World Heritage Area contain 1660 km2 of saltmarsh habitat.70 This represents over 40 per cent of the combined area of mangrove and saltmarsh found along the GBR coast, and approximately 12 per cent of Australia’s saltmarsh habitats (13 595 km2).10 Catchment runoff What does the Outlook Report say about catchment runoff? The Great Barrier Reef, especially much of its inshore area, is being affected by increased sediments, nutrients and pesticides in catchment runoff. With recent advances in agricultural practices and the uptake of additional government programs, there has been a reduction in sediment and nutrient inputs into some coastal river systems. A long lag time is expected before there are positive effects on marine water quality. The community knowledge base has increased, especially where water quality improvement plans are in place and there are high levels of volunteer involvement in fieldwork and monitoring programs. Changes in water quality affect the biodiversity of reef systems. For example, higher concentrations of pollutants such as suspended sediments, nitrogen and phosphorus, may result in more macroalgae and less hard coral diversity. Such a shift affects the overall resilience of the ecosystem. The effects of degraded water quality on the Great Barrier Reef include the reduction of hard coral cover at some inshore reefs; the increase of diseases and crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks; and a reduced ability for coral reefs to recover from bleaching or crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks. A decline in inshore habitats as a result of polluted water will have economic and social implications for industries and communities that derive an income from these areas. Potential economic implications include declines in fish populations important for fishing. How effectively is catchment runoff managed? Catchment runoff and associated water quality is identified in the Outlook Report as the second most significant pressure on the Reef and is expected to have significant compounding effects with climate change. Water quality is a social as well as environmental issue and is being addressed as such by managers. The knowledge base relevant to water quality within the managing agencies has increased in the last three to five years. Introduction of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Aquaculture) Regulations 2000 resulted in a significant improvement in the environmental performance of land-based aquaculture facilities. The Report recognises that management of issues like water quality and catchment runoff are challenging given the broad scale and complex jurisdiction involved. Substantial resources are being provided to improve the water quality of the Great Barrier Reef, but progress is slow and patchy. The Report acknowledges that effective implementation of actions under the Reef Water Quality Protection Plan and Reef Rescue initiative will contribute to improvements in water quality; however improvements are likely to take many years to be translated into measurable changes. CE1884 - 040809 The Great Barrier Reef receives the runoff from 38 major catchments which drain 424 000 km2 of coastal Queensland. Over the past 150 years sediment inflow onto the Great Barrier Reef has increased four to five times, and five to 10 fold for some catchments. Inorganic nitrogen and phosphorous continue to enter the Great Barrier Reef at enhanced levels, two to five times for nitrogen and four to 10 times for phosphorous relative to preEuropean settlement and pesticides are now being detected in inshore waters. Fishing What does the Outlook Report say about fishing? Fishing on the Great Barrier Reef is an important pastime and source of income for both Queensland coastal communities and the Queensland seafood industry. This use of the Great Barrier Reef contributes strongly to the regional and national economy. A viable commercial fishing industry depends on a healthy ecosystem. Likewise, Queenslanders rely on a healthy Reef for recreation and as a source of local seafood. They too are keen to ensure this natural resource remains healthy. While the Great Barrier Reef is one of the best managed marine ecosystems in the world, it is clear that climate change is a major threat to its plants, animals and habitats. There is likely to be flow-on effects to the communities and industries that depend on the Great Barrier Reef. It is likely that many aspects associated with fishing may be highly sensitive to climate change. There may be changes in fish abundance and survival, fish size and distribution (e.g. homing ability) as well as changes in cyclonic and storm activity that will affect fisheries resources. Fishers may also have to modify their fishing practices in response to disruptions to shallow-water nursery grounds (such as mangroves and seagrass beds), disturbance to coral reef habitats from more severe coral bleaching, more intense cyclones, altered species distribution from the effects of sea level rise and increasing sea temperatures and changing sea chemistry. Climate change will impact on global fisheries production patterns and is likely to increase demand for wild caught seafood, including from the Great Barrier Reef, and are likely to drive a diversification of species targeted and locations fished. Sustainable fishing is vital to the long-term future of both the resource and the community, and the industry is working with Marine Park managers, fisheries managers and research institutions to identify adaptation measures that will future-proof their industry. How effectively is fishing managed in the Marine Park? Fishing activities are required to comply with Marine Park zoning, and this results in about 67 per cent of the Marine Park being available for various types of fishing. Fisheries are directly managed by the Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries. Commercial fisheries may also be required to meet national standards to gain approval for export of product under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. There have been significant improvements made in reducing the impacts of fishing in the Great Barrier Reef, such as by-catch reduction devices, effort controls, and the introduction of total allowable catches, revised possession and size limits and increasingly the adoption of tag and release fishing. The Outlook Report identifies that although progress is being made towards best practice fisheries management, a number of risks remain. The high level risks identified are: extraction of top order predators (e.g. sharks), incidental catch of protected species and other species of conservation concern, illegal fishing (foreign and domestic) and death of discarded (by-catch) species. The Report also identifies that the limited information available means that the ecosystem level impacts of fishing are not well understood. Climate change What does the Outlook Report say about climate change and the Great Barrier Reef? Future predictions of climate change dominate most aspects of the Great Barrier Reef's outlook. Impacts from climate change have already been witnessed and all parts of the ecosystem are vulnerable to its increasing effects, with coral reef habitats the most vulnerable. Marine turtles and seabirds are also likely to be highly vulnerable. Changes to the ecosystem because of climate change are likely to have serious implications for dependent industries and communities. The average annual sea surface temperature on the Great Barrier Reef is likely to continue to rise over the coming century and could be as much as 1°C to 3°C warmer than the present average temperatures by 2100. In the last decade there have been two severe mass coral bleaching events resulting from prolonged elevated sea temperatures. In addition, Great Barrier Reef waters are predicted to become more acidic with even relatively small increases in ocean acidity decreasing the capacity of corals to build skeletons and therefore create habitat for reef biodiversity in general. Sea level on the Great Barrier Reef has already risen by approximately 3mm per year since 1991. Changes in the climate also mean that weather events are likely to become more severe. Almost all Great Barrier Reef species and habitats will be affected by climate change, some seriously. The extent and persistence of the damage will depend to a large degree on the extent to which climate change is addressed worldwide and on the resilience of the ecosystem in the immediate future. How effective is the management of climate change and the Great Barrier Reef? In the Outlook Report, only those proactive and adaptive management measures undertaken specifically to protect and manage the Great Barrier Reef in relation to climate change were evaluated. The broader national and global initiatives to address climate change were not considered. The management agencies responsible for the Great Barrier Reef are contributing significantly to the development of international best practice for managing climate change issues as they relate to coral reef ecosystems. A comprehensive vulnerability assessment for the Great Barrier Reef provides good contextual information for management of climate change impacts. Key threats such as increasing sea temperatures, ocean acidification, sea level rise and increased severity of storm events are recognised. Significant resources are being allocated by all levels of government and industry to assess threats and develop adaptation plans, and measures are in place for many aspects relating to the Great Barrier Reef. For example, the implementation of the $8.9 million Great Barrier Reef Climate Change Action Plan is aimed at understanding the vulnerability of the Great Barrier Reef and helping to build resilience to climate change in the ecosystem and the communities and industries that depend on it. The Outlook Report recognises that for all these plans and measures, the challenge remains to translate them into specific policies and measurable on-ground actions. For some, pilot programs are being undertaken at demonstration sites to capture lessons which can be applied elsewhere. There is successful community engagement on climate change through programs such as Bleachwatch, Reef Guardian Schools and tourism industry input including via eco-certification. Partnerships to reduce carbon footprints and increase stewardship are being developed with the fishing industry. The Outlook Report acknowledges that ultimately, if changes to the world's climate become too severe, no management actions will be able to climate-proof the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem.