z2p001153459so1

advertisement

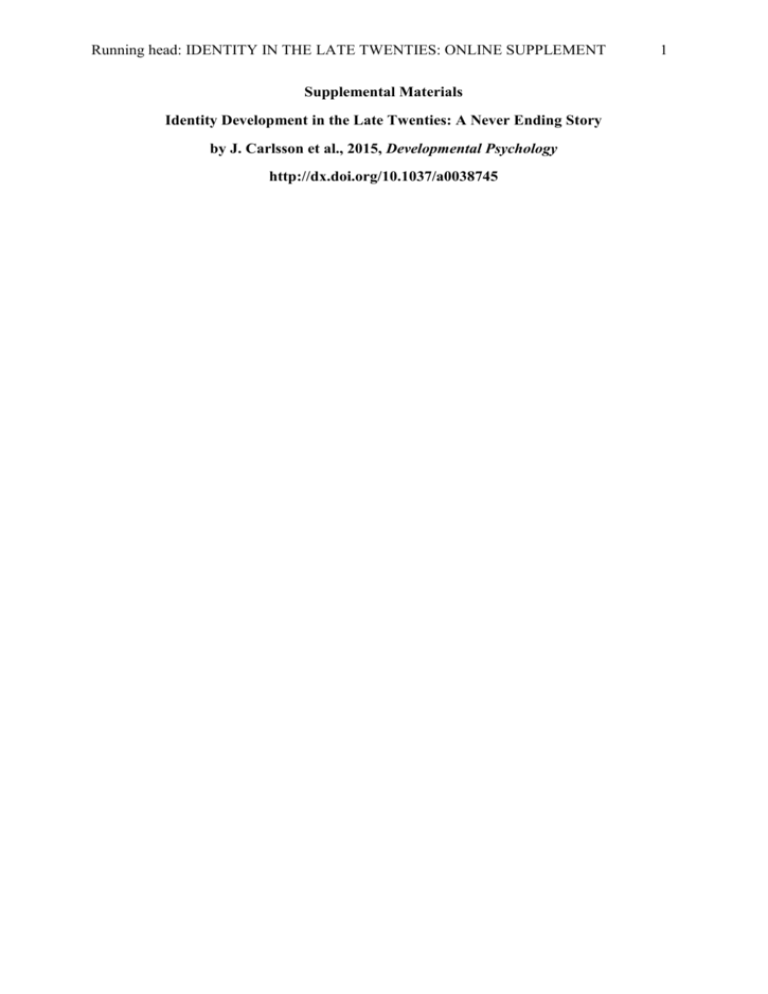

Running head: IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT Supplemental Materials Identity Development in the Late Twenties: A Never Ending Story by J. Carlsson et al., 2015, Developmental Psychology http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038745 1 IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 2 - Online Supplement About Analyze Procedure and Coding Scheme General Information About the Analysis The analysis concerned 55 participants that were assigned to either identity achievement (n = 32) or foreclosure (n = 23) at both age 25 and age 29. The identity status interview (Marcia, 1966; Marcia, Waterman, Mattesson, Archer, & Orlofsky, 1993) included the same four identity domains at both age 25 and age 29: occupation, romantic relationship/marriage, parenthood, and priorities between family and work. Case summaries (described in more detail below), of similarities and differences between each individual’s identity narrative from age 25 and from age 29 were analyzed. The analysis was performed in five steps: 1. Similarities and differences between individuals’ interview narratives from age 25 and age 29 were summarized for a subset of 15 participants. This resulted in 15 case summaries. 2. A thematic analysis of these 15 case summaries was conducted. 3. A coding scheme was constructed based on the thematic analysis. 4. Similarities and differences between individuals’ interview narratives from age 25 and age 29 were summarized for the 40 remaining participants. These 40 case summaries were coded according to the coding scheme developed in the previous step. 5. Reliability testing. The five steps and the coding scheme are described in detail below. 1. Case Summaries IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 3 In the first step a subset of 15 participants, both women and men, was analyzed. This subset included seven participants assigned to identity achievement at both age 25 and age 29 and eight participants assigned to foreclosure at both interview occasions. Each of the 15 participants was treated as a singular case study. The case study methodology allows for a holistic, yet detailed, view of complex phenomena (Yin, 2009). Thus, the use of a case study approach in this part of the analysis contributed to retention of the characteristics of each individual’s process of identity development. In this step each participant’s interview narrative at age 25 was compared with her/his interview narrative at age 29. Differences and similarities between the interview narratives from age 25 and age 29 were summarized for each participant. In these case summaries the content of each identity domain at age 25 was compared with the content of the same identity domain at age 29. Including how the participants’ descriptions of how they reached their identity commitments changed between the interview occasions and a comparisons of how the participants talked about what and who had influenced their identity development at the different interview occasions. 2. Thematic Analysis The 15 case summaries were analyzed with an inductive thematic approach. Thematic analysis is used for systematic identification and analysis of patterns, or themes, in the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The analysis started with a close examination of six case summaries, which included both female and male participants assigned to both identity achievement and foreclosure. The three authors together identified patterns of stability and change in these six case summaries. The authors’ analyses of the data were discussed in relation to the case summaries and the original interview transcripts, until agreement was reached. Initially, several themes of stability and change between age 25 and age 29 were identified. These themes were very specific and close to the manifest content of the interview summaries. One IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 4 large pattern was also identified at this point in the analysis: some narratives were deepened and further developed between the interview occasions, whereas others were weaker and shallower at age 29 than at age 25. Building on this pattern and the identified themes a preliminary model and a preliminary coding scheme were then constructed. In this process, the initially identified patterns and themes were grouped together into a model that included three overarching dimensional themes stretching between the two endpoints of weakening and deepening of the identity narrative (described in the final coding scheme below). The first author applied this coding scheme to the rest of the 15 case summaries (n = 9). All three authors examined the coding of these nine case summaries in relation to the case summaries themselves, resulting in smaller alterations in the descriptions of the dimensions. After this the dimensions were named and the final model and coding scheme was developed. 3. Coding Scheme The structure of this coding scheme is shown in Figure S1. The coding scheme includes three dimensions: ‘Approach to changing life conditions’, ‘Meaning making’, and ‘Development of personal life direction’. These dimensions concern different aspects of the development of identity narratives on the continuum between two endpoints; weakening of identity narrative and deepening of identity narrative. The weakening endpoint reflects a shallower identity narrative that has not evolved between the interview occasions. The deepening endpoint reflects a richer narrative that has evolved between the interview occasions. IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 5 Figure S1. Illustration of coding scheme. The continuous nature of the dimensions indicate that case summaries of participants’ interview narratives could fit anywhere between the two endpoints of each dimension. However, in the coding scheme each of the three dimensions was divided into three broad categories to facilitate the coding; one category at the deepening end, one at the weakening end, and one in the middle. Coding criteria for the dimensions are described below. Dimension 1: Approach to Changing Life Conditions This dimension concerned the participants’ approach to the fact that life is inevitably changing as time goes by. The dimension describes the participants’ willingness or capacity to reformulate and adjust their identity narratives in relation to changing life conditions. The coding focused on the differences and similarities that were observed between participants’ descriptions of their identity commitments at age 25 and age 29. It was the observed change in IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 6 the identity narrative that was coded and the participants themselves did not always describe how or why the change occurred. The three categories in the coding scheme for this dimension were: Category 1.1 – Weakening of identity narrative. Case summaries that indicated unwillingness or incapability to reform and adjust the identity narrative in relation to life changes were coded to this category. Because these participants’ identity narratives did not correspond well with the surrounding context they were considered weakened. Case summaries that were coded to this category indicated that the identity narrative was rigid and resistant to change. That is, these case summaries included indications of identity commitments that were firm and in-flexible even when they did not seem to be a good fit with these participants’ everyday lives. Moreover, case summaries were coded to this category when they indicated that there was incoherence between participants’ identity commitments and their actions in their everyday life. That is, the participants’ statements concerning how they wanted to live their life did not match their descriptions of their actual behavior. Category 1.2 – Middle part of the dimension. Case summaries from participants who described very similar identity commitments at both age 25 and age 29 were coded to this category, if they did not show indication of incapacity or unwillingness to reform their identity narratives to changes in life. That is, the case summaries coded to this category did not show indications of that the participants had adjusted their identity narratives to changes between the interview occasions, but at the same time they showed no indications of that the participants’ current identity commitment was a bad fit for their everyday life or incoherent with their actions. Participants who showed unwillingness or incapability to reform and adjust their identity narratives in some identity domains but had adjusted to life changes in others were also assigned to this category, because the overall impression of these case summaries was that they were in-between the two endpoints of this dimension. IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 7 Category 1.3 – Deepening of identity narrative. Case summaries that indicated that the participants had reformed and adjusted their identity narratives between the interview occasions were assigned to this category. Case summaries were coded here if the comparison between their narratives at age 25 and age 29 indicated that the participant had evolved and modified their identity commitments between the interview occasions. Case summaries that indicated that participants had changed one or more identity commitments entirely between the two interview occasions were also coded here. Dimension 2: Meaning Making This dimension concerns new elements of meaning in the identity narrative at age 29 compared to the narrative at age 25. The term meaning making is common in narrative research of identity formation where it refers to how individuals create and maintain a sense of identity by reflecting upon specific life events and past experiences, what they have learned from these experiences, and what insights they have gained from them (e. g., McLean & Thorne, 2003). In this study the coding was focused on the extent to which the elements of meaning making in participants’ identity narratives had changed between age 25 and age 29 (for example, if there were new elements included or if there were less signs of meaning making at 29 compared to 25). Elements of meaning making in the identity narratives included reflections about how the participants had developed their identity commitments, description of influences on their choices, sharing of memories in the interview narrative, and elaborated descriptions about how the participants wanted to behave in different roles in life. The three categories included in this dimension were: Category 2.1 – Weakening of the identity narrative. Because poelpe continuously enconter events of which they may need to make meaning case summaries that showed a very small, or no, increase in the amount of elements of meaning making between the two interview occasions were assigned to this category. These case summaries indicated that the IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 8 participants had made few new reflections upon their identities between the interview occasions. Category 2.2 – Middle part of the dimension. Case summaries assigned to this category showed some increase in meaning making between the interview occasions, but this increase was limited to specific aspects of the identity narrative. These case summaries indicated that the participants had made some new reflections about parts of their identities between the interview occasions. Category 2.3 – Deepening of identity narrative. Case summaries assigned to this category showed a substantial increase in meaning between the interview occasions that was not limited to specific aspects of the identity narrative. These case summaries indicated that the participants had made many new reflections about their overall identities between the interview occasions. Dimension 3: Development of Personal Life Direction This dimension concerns the participants’ development of their personal life direction between the interview occasions. The dimension illustrates how the participants’ descriptions of how they make decisions about how they want to live their lives changed between the interview occasions. The three categories included in this dimension were: Category 3.1 – Weakening of identity narrative. Case summaries that indicated that the development of personal life direction was increasingly constrained by social norms and expectations from others at age 29 compared with age 25 were coded to this category. These case summaries indicated that in their descriptions about how they made decisions about how they want to live their lives the participants were more preoccupied with following social norms and expectations from others at age 29 compared to age 25. This preoccupation could, for example, be seen in an increased worry about what other people would think about the ways in which they lived their lives. IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 9 Category 3.2 – Middle part of the dimension. Case summaries from participants whose identity narrative showed no change in the development of their personal life direction between the interview occasions were assigned to this category. Because it was the change between interview occasions that was coded case summaries that were assigned to this category could indicate that at both interview occasions the participant was highly dependent on social norms and expectations from others or that at both interview occasions the participant had a strong agency to act and make independent life decisions. As long as no change between the interview occasions could be observed case summaries were coded to this category. Category 3.3 – Deepening of identity narrative. Case summaries that indicated an increased development of personal life direction between the interview occasions were assigned to this category. Case summaries were coded here if they indicated that between the interview occasions the participants had increased their agency to act and make independent decisions about how they want to live their lives in relation to social norms and expectations from other people. Case summaries that were coded to this category could still indicate that the participants followed social norms and expectations from others. However, to be assigned to this category the case summary needed to indicate that the participant had reflected more upon how she or he was affected by norms and expectations from others. An example of such reflections was to acknowledge how different life styles are possible for both themselves and for other people. 4. Coding The fourth step in the analysis involved coding of the interviews from the 40 remaining participants who were assigned to either identity achievement or foreclosure at both age 25 and age 29. Differences and similarities between the identity narrative from age 25 and age 29 was summarized for each of these participants separately. These 40 case IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 10 summaries where then coded by the first author in accordance with the final coding scheme described in step 3. 5. Reliability Testing To ensure reliability the second author recoded a random sample of case summaries (n = 20) according to the coding scheme. The reliability was tested with percentage of exact agreement and weighted kappa (Cohen, 1968). The kappa was weighted so that a disagreement between the categories at the deepening and weakening endpoints of each dimension had a larger negative impact on the kappa value than a disagreement between any of the endpoint categories and the middle category. The overall exact agreement between first and second author was 75% with an average linear weighted kappa of .68. For the approach to changing life condition dimension exact agreement was 75% with linear weighted kappa of .66. For the meaning making dimension exact agreement was 70% with linear weighted kappa of .63. For the development of personal life direction dimension the exact agreement was 80% with linear weighted kappa of .74. IDENTITY IN THE LATE TWENTIES: ONLINE SUPPLEMENT 11 References Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa Cohen, J. (1968). Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scale disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin, 70, 213-220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256 Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551-558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281 Marcia, J. E., Waterman, A. S., Mattesson, D. R., Archer, S. L., & Orlofsky, J. L. (Eds.). (1993). Ego identity. A handbook for psychosocial research. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. McLean, K. C., & Thorne, A. (2003). Late adolescents' self-defining memories and relationships. Developmental Psychology, 39, 635-645. doi: 10.1037/00121649.39.4.635 Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousend Oaks, CA: Sage.