merchjc8 - Bryn Mawr College

advertisement

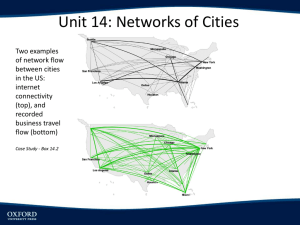

Corridors of Consumption: Mid-19th-century Commercial Spaces and the Reinvention of Downtown Jeffrey A. Cohen, Bryn Mawr College, 15 June 11 The industrial revolution created new landscapes of production that soon found a counterpart in dramatically transformed landscapes of consumption. The 19th-century city quickly became a place unlike any previous urban iteration, brimming with goods manufactured elsewhere, and bursting with additional population drawn to the new urban economy, often doubling and doubling again in succeeding decades. A landscape of consumption had not only to accommodate such activities, but also to announce them, to identify its offerings and its invitation to customers by a range of means, from signboards to architectural individualization, proffered on the street as well as through surrogates on paper. Fig. 1. Detail of W. Stephenson & Co., "View of Park Place, New York. from Broadway to Church Street. North Side," 1855 (Museum of the City of New York, 29.100.2285). Note the surviving formerly residential stoops and doorways at no 13, in yellow at center, and no. 3, four buildings to the right, interspersed alongside newly built loft buildings. In piecemeal ways reflecting small-scale agency, businesses adapted directly to their place in this changing city and its shifted spectrum of functions, creating a dense yet heterogeneous streetscape. New patterns and typologies of building became dominant in a markedly expanded realm of commerce that in larger cities constituted thousands of narrow-fronted stores shouldering each other for a foothold in frontage on solidly builtup streets (fig. 1). Different business functions sorted themselves so that high-end or high-volume retail and recreational venues would vie for the most visible locations, often claiming areas that had accommodated elite residential use, arraying themselves in continuously bounded linear corridors along thoroughfares leading across or outward from the old urban core. Retailers recognized the need for their stores to invite entry, to be visibly distinct from private homes or workplaces. Their identification also needed to be more specific, assertively declaring a line of business, and even distinguishing individual stores in the same line from one another. This part of the city quickly became a dense and visually competitive matrix. Space here was valuable and voids were short-lived, both on the ground and in elevation, where facades were crowded by insistent signboards, painted promotional messages, and display windows beckoning the eyes and then the feet of passersby. Architecturally, this was a changeful place, with structures at first adapted and then rebuilt for business. Once strikingly new, this commercial landscape of the mid-19th century city soon proved remarkably ephemeral, with buildings often replaced within a generation or two, despite their solid construction. At the heart of of this emerging central business district, many were consumed by the sharply accelerating land values and the growing ability to build tall using iron, and then taller using steel in the last decades of the century. This chapter will explore the form of that earlier, now largely lost city of commerce, a district of many small pieces rather than its successor, of larger pieces, well known from survivals and turn-of-the-century photographs focused upon preening office towers and block-long department stores. The character of that earlier city persists, though, in occasional remaining clusters of survival and scatterings of relatively obscure visual documents. These range from detailed ward atlases and fire insurance surveys to early 2 photographs and advertising materials. Also valuable are contextualizing images that document not just the most elaborated, architect-designed commercial buildings, but also the more typical ones that formed the far greater part of this new urban landscape. Especially valuable are records pertaining to a key component type, the individual business building of the mid-century, tall, narrow, and deep, that served retailers, wholesalers, importers, and small-scale manufacturers. In these elements of the mid19th-century streetscape -- as built, as projected in signage, and as represented in advertising -- one discerns the enacted motives of businesses shaping their individual presence, and their aggregation into patterns that collectively defined some of the most visible and characteristic aspects of this early version of the modern city. * * * Newly Big Cities Perhaps the most concise and concretely measurable indication of the scope of this change lies in population statistics for cities tied to the industrializing economy. Manchester, England, one of the first cities to experience this transformation, offers a pattern that would be revisited again and again in other cities. The city's population ascended at an astounding pace: Manchester (given roughly for the city itself, in thousands): 1750: 18k 1801: 90k 1831: 182k 1851: 303k 1861: 338k 1881: 342k This leap occurred early in Manchester, leveling off close to mid century, when many other cities were just starting to show similarly explosive rates of growth. Approximate numbers for other cities track comparable changes in population: London 1750: 675k 1801: 959k Birmingham 1750: 24k 1801: 74k 1861: 2,804k 1881: 3,815k 1831: 147k New York City 1800: 61k 1820: 124k 1840: 313k Philadelphia (county, then city): 1800: 81k 1820: 137k 1840: 258k Berlin 1775: 136k 1800: 173k 1825: 220k 1851: 223k 1871: 344k 1891: 478k 1860: 814k 1880: 1,217k 1900: 3,437k 1860: 566k 1880: 847k 1900: 1,293k 1840: 329k 1875: 969k 1900: 1,889k 3 Hamburg/Altona 1800: 120k 1850: 205k Leipzig 1800: 32k 1850: 62k Vienna 1800: 232k 1857: 476k Budapest 1800: 61k 1831: 105k St. Petersburg 1800: 270k 1850: 490k Paris: 1750: 565k Lyon 1800: 110k 1890: 712k 1890: 357k 1890: 1,342k 1869: 254k 1890: 492k 1890: 1,003k 1801: 548k 1851: 1,053k 1850: 177k 1890: 429k 1 1890: 2,537k The key issue here is not the comparison between cities so much as the precipitous growth within each. Of course, legal city boundaries and successive annexations varied in their inclusion of associated industrial landscapes, especially when mills were waterpowered or dependent on peripheral canal and then rail networks. And the population growth of many cities in the 19th century was less directly connected to their own manufacturing prowess than to their expanding role as major transportation, administrative, or financial centers. But the pattern was unmistakable. The new economies of mechanized production in Western Europe and the North America meant cities were drawing workers from farms to urban factories, and then to stores and offices, at an unprecedented rate.2 The local circumstances of urban immigration, from agricultural or political push or pull and other factors, could critically condition this movement of people, but the base fact is that city employment was able to absorb newcomers, and at some base level, population growth was a measure of the much enlarged capacity of these urban economies. 1 Adna Ferrin Weber, The Growth of Cities in the Nineteenth Century (orig. publ. NY, 1899), esp. p. 450; "List of towns and cities in England by historical population," Wikipedia, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_towns_and_cities_in_England_by_historical_population], revision of 14 May 2011; and other statistical sources. 2 Kingsley Davis, "The Urbanization of the Human Population," Scientific American 213, no. 3 (September 1965):40-53; Weber, Growth of Cities, pp. 154-229. 4 Many of the new city residents, especially in European cities, may have come to industrializing workplaces from tenancy on large agricultural holdings, and were now entering the money economy in a more substantial way, purchasing food, clothing, shelter, and anything else they could not produce for themselves, becoming consumers in a city of strangers brought into contact by such transactions. But others belonged to expanding middling and newly wealthy classes who prospered substantially in connection in this new environment, and who propelled an economy of elite consumption that would itself reshape the city's center. U.S cities experienced the same explosion in population, attracting domestic immigrants from the countryside along with foreign immigrants in a precipitous trend most revealingly expressed in the percentage of urban residents in the population at large. Urban areas accounted for well under 4% of the U.S. population in 1790 -- attesting to the primarily agricultural work of most Americans. Living in the city, very visible in our imaginations, had been statistically exceptional. But by 1850, the city was home to more than 15% of the U.S. population, and by the end of the century, by 1890, to nearly 30%. And that proportion would continue to ascend steeply through the 20 th century, reaching into the high 70s.3 Differentiated Geographies With such an influx of new city dwellers, the most obvious visible change in 19thcentury cities was a massive expansion of their densely settled area, often seen as a hatched amoebic shape hungrily advancing within (and often beyond) the larger legal boundary of the city, as one sees in successive maps of those cities. The growing builtup area after the mid-19th century could easily dwarf that from early in the century. 3 Weber, Growth of Cities, pp. 20-40; James H. Kunstler, The Geography of Nowhere (New York, 1994); Joel Garreau, Edge City (New York, 1991). 5 The homogeneity of that hatching, however, belies areas of increasingly pronounced differentiation within the built-up area. The outer edges sometimes marked the reach of densely built working-class housing on the cheapest hitherto-undeveloped land nearest the periphery. Just within or just beyond that (depending on a map's graphic conventions), especially in Anglo-American cities one might find an airier zone of detached villas and cottages in a suburbanizing fringe reached by rail, whether via horse-drawn streetcars or commuter railroads. Depending on when they were built, industrial districts might have located either nearer to or further from the old urban core than these suburbanizing zones, easily crossing concentric patterns to hug lines of waterways or rails that would bring them raw materials, provide power or fuel, and permit their products to reach markets. And the irregular perimeter would usually distend outward into "pseudopodia" along the older radial roads leaving the city. Less visible on large maps but more topical for the present study were the changes occurring within the urban core. Businesses, multiplying enormously in number, sought these central locations, outbidding nearly every other use of the land there that had not been claimed by immovable civic institutions. A new "downtown" devoted almost exclusively to commerce displaced sites of housing, especially of townhouses and mansions whose elite residents moved successively "uptown" into new residential corridors, into adjoining neighborhoods, or out to those new suburban peripheries. And somewhere adjacent to the old downtowns, usually in realms extending perpendicularly from the base of the downtown/uptown axis, were often districts where many of the urban poor crowded into aging houses adapted as multiple residences, into newly built tenements that took their place, or along the narrow interior alleys and courts within large blocks. The showplace of this reconfigured city, though, was that new downtown, recast by the desires of a dramatically expanding cohort who had disposable means and an avid hunger to consume. They bought goods, services, and even experiences through which they performed the prerogatives of their newly achieved economic standing, 6 patronizing venues from jewelers' and haberdashers' shops to photography studios, theaters, and elegant restaurants. Such venues for the rising bourgeoisie to equip, entertain, and display itself were often aligned along the principal thoroughfares, welltraveled and highly visible, where they crossed the older urban core. These were the subjects of many prints of the period, especially some long, nearly elevational viewseries that captured their assertive presence, density, and well-trafficked setting. Such elite retail corridors often shared the center of the modernizing, mid-19th-century city with a network of intersecting streets. These made up an emerging and more varied district of business just off that corridor, mixing wholesale and small-scale manufacturing with retail, accommodating jobbers who provided materials, intermediate products, and services to other merchants and manufacturers, and quartering activities ranging from selling highly specialized, but less "fancy" goods, to office space for Fig. 2. Detail of E. Jones, New York Pictorial Business Directory of Maiden Lane (New York, 1849), plate 1. (Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society). the growing number of white-collar workers in finance, insurance, transportation, newspapers, and various other business functions. Images from 1849 of the initial blocks of Maiden Lane near Broadway (fig. 2), for example, identified importers of watches, perfume, and "fancy goods," jewelers, sellers of gas fixtures, hats, guns, cutlery, makers of watch cases, gold pens, and pocket books, alongside sellers of cloth, 7 linen, clothing, hosiery, shirts, and generic dry goods, some indicating both "wholesale and retail." As one moved further down the block, away from Broadway and toward the East River docks, the goods grew less elite -- varnishes, drugs, oil cloths, boots, combs, trunks, paper hangings, and trimmings, window glass, printers, oils, paints -- and words such as "wholesale" and "warehouse" appeared more frequently. Further south, Wall Street, already a financial center when it was recorded in a similar set of street-views from 1850, showed an interdependency in the clustering of insurers, brokers, and commission merchants, printers and stationers, express companies and auctioneers near the banks that were the street's iconic presences. These constituted a special linear precinct within a much larger matrix of intersecting streets that mediated between the fashionable consumer on Broadway and the port at river's edge, with much of this landscape devoted to business-to-business trade of varied types. Fig. 3. Detail of E. Whitefield, "Map of the Business Portion of Chicago," 1862, Chicago Historical Society (ICHi-27737). 8 Such districts were often the destination of visiting businessmen, intent on acquiring goods or equipment that could be inspected, ordered, and shipped out to their distant stores or factories. A rare artifact serving their navigation within this changeful realm is a type of commercial map, such as E. Whitefield's "Map of the Business Portion of Chicago," 1862 (fig. 3); other examples record analogous portions of Boston (1869), New Orleans (1883) and Mexico City (1883), both of the latter seemingly made by one entrepreneurial and well-traveled engineer.4 The constrained scope and selective identification on such maps reflect their purposeful focus upon a functional geography that was inscribed within a more heterogeneous one, with unmarked sites and peripheries that mapped to others' uses. Early Commercial Building Types This expanding claim of business upon downtown territory is perhaps best demonstrated by the color-coding of some of the earliest highly detailed maps of such areas, in large-scale atlases that are often generically referenced as "Sanborns" -- real estate or fire insurance atlases of unprecedented scale and coverage that began to appear in some large cities in the 1850s. These clearly reveal this sweeping tide: in the Perris maps of lower Manhattan (fig. 4), the advancing bluish tone, especially along Broadway, at right, indicates "brick or stone stores" without dwelling space above, distinguished from the pink of homes or combined-use buildings nearby. One recognizes the same patterns in Philadelphia, as shown in the Hexamer and Locher 4 Other examples of what may have been a more widespread but rarely preserved graphic species include: • B. B. Russell publisher, "Nanitz' Great Mercantile Map of Boston" (Boston, 1869), Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library (G3764.B6 1869 .N3) (http://maps.bpl.org/details_10490/?dl_pp=11&mtid=5). • J. Popper, publisher, "Map of Central Business District and Mouth of Mississippi River" (New Orleans, 1883), Historic New Orleans Collection (acc. no. 1955.7i.ii) • Julio Popper Ferry, "Plano del perimetro central, directorio comerical de la Ciudad de Mexico" (Mexico City, 1883), David Rumsey Historical Map Collection (image no. 3302000). Popper and Popper Ferry seem to be one and the same character, better known for his slightly later adventures in Argentina in pursuit of gold. 9 atlas plates of the commercial sector there from 1858-60, with business buildings colorcoded in a green tone.5 In both cases, these fully commercial buildings show the same distinctive footprint of nearly full-lot coverage, whereas neighboring houses (or former houses summarily adapted to commerce), were rendered in pinkish hues and typically show substantial back yards, usually only partly built into with rear ells. In these two Fig. 4. Detail of William Perris, Maps of the city of New York, surveyed under directions of insurance companies of said city, vol. 1. (New York, 1852), pl. 9 (Courtesy NYPL Digital Gallery, Image ID: 1270007). cities, such detailed and comprehensive cadastral records only date back to near midcentury, denying us comparable counterpart images from the prior decades, but later iterations show the same process playing out as the commercial core expanded, with open space to the rear and sides of lots, along with residential setbacks in front, being consumed by enlarged footprints as businesses rebuilt to suit its needs. One gets a fuller sense of the typical component of such districts through two more particularizing kinds of record. One of these is commonly called a “trade card,” although it is a species of trade card that is far larger than one might expect, and might be more 5 Ernest Hexamer and William Locher, Maps of the City of Philadelphia, 7 vols. (Philadelphia, 1858-1860), fully digitized as part of the Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network at http://www.philageohistory.org/rdic-images/index2.cfm#:::HXL1858::]. 10 accurately referenced as an illustrated advertising broadside.6 These vary greatly in character and number from city to city, perhaps partly reflecting the entrepreneurial bent of individual lithographers in each who pursued this line and of the merchants there who engaged them. Philadelphia seems to have a tradition of both, and experienced an extraordinary flurry of hundreds of these from the decades before and after mid-century (or perhaps of preservation and knowledge of these usually ephemeral images, as many known examples seem to be unique ones). They were typically large sheets with detailed lithographed images of a business, sometimes of its factory, sometimes of its showroom, sometimes of its products, but quite often of the exterior of its downtown quarters. Scores of these survive to show excerpted glimpses of parts of antebellum business districts, usually as frontal views animated by signage, wares, and streetside life.7 The key building type they often show was already rather fully developed by the 1830s, with its ground story opened up between vertical stone piers, typically marble or granite, and tall windows within tall floors usually rising above the older residential doublepitched and dormered roofs, often to a full-height third, fourth, or even fifth story. Building fronts might be two to four windows across on their upper stories, but where an individual store in Philadelphia had a 17 to 22-foot front, as most did, the central ground-story opening would often be a window over a bulkhead, flanked by wide doorways to each side. Much of the upper floor space might be dedicated to storage, 6 Robert Jay, The Trade Card in Nineteenth-Century America (Columbia, MO, 1987), pp. 20-21. 7 Nicholas B. Wainwright, Philadelphia in the Romantic Age of Lithography (Philadelphia, 1958); Library Company of Philadelphia, "Philadelphia on Stone Digital Catalog" [http://www.librarycompany.org/pos/poscatalog.htm]. My thanks to Jenny Ambrose for providing the text and images for her paper, “Picturing Factories and Storefronts,” given at the North American Print Conference in September 2007. 11 Fig. 5a. W. L. Breton, [Charles Egner store, 10 North Third Street,], ca. 1837. Library Company of Philadelphia (W460 [P.2244]). Fig. 5b. W. H. Rease, [Conrad & Roberts hardware & cutlery, 123 N. Third Street], 1846, Library Company of Philadelphia (W83 [P.2025]). Fig. 5c. [J. Mayland, Jr. & Co. tobacco & snuff manufactory. Segars, foreign & domestic. Wholesale grocers, N.W. corner of Third and Race Streets], 1846, Library Company of Philadelphia (W193 [P.2053]). breaking bulk quantities, or processing of goods, and the hoists for hauling such materials were usually located in one of the end bays, sometimes betrayed by a loop of rope or a rising barrel in one doorway in these prints. Such trade cards can almost always be combined with evidence from those early realestate-atlas plates to connect the building face with its built context and footprint, but one can also get inside these buildings as they were configured when new through detailed plans and written descriptions made when the properties were surveyed by fire insurance companies. Tens of thousands of these surveys dating from the 1820s to the 1890s survive in Philadelphia archives, many offering much the same plan for purposebuilt commercial buildings. Scores of plans of this sort of building survive in these collections. In what appears to be their mature form of the late 1830s, they were usually very deep, clear-span spaces 12 meant to flexibly accommodate a range of activities, often with different firms on different floors served by a closed staircase that ran longitudinally along one blind party Fig. 6a. Fire insurance survey of 43 N. Front, 1829 for Aaron Killé. (survey no. 0: 35, Franklin Fire Insurance policy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania). Fig. 6b. Fire insurance survey of 16 N. 4th St., 1837 for John Grigg (survey no. 0: 1941, Franklin Fire Insurance policy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania). Fig. 6c. Fire insurance survey of 41 N. 3rd St., 1869 for Pennock Estate (survey no. 262: 37404, Franklin Fire Insurance policy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania). wall -- with successively more distant landings for each floor. The rope hoist and the hatchway opened through each floor, sometimes right in front of the start of the staircase. The large front space could go back as much as 80 or 100 feet, and sometimes even more on Philadelphia’s unusually deep blocks, but it was often set off 13 from a “counting room” at the rear, which often connected to a much smaller “fireproof” for critical records and valuables. Both of the latter might open onto a shallow rear court or “area,” bringing a modicum of daylight to these office functions, and there were sometimes skylights in the counting rooms or above the taller main volume, along with additional setbacks on upper floors to bring light into these very deep, dark floor plates, typically blind along both party walls. This plain, adaptable form appears to have been a rather common building type around mid-century, adopted for a wide range of commercial purposes. One spies much this form in many period views of commercial districts from the period in the U.S. and elsewhere, and one encounters some surviving instances of it along early commercial streets. With modifications, it was also a staple of the early financial and office district, although there, elevated stoops and half-sunken basement offices, such as one sees in the Wall Street views from 1850,8 may have reflected the diminished importance of eyecatching shop-windows for this type of business; their lack of a need to deal with physical goods in bulk, which would have favored grade-level connections; and the intense desire among such businesses for proximity to finance on such a block -making attractive even spaces a half-story below grade, where one would find express offices, exchange brokers, auctioneers, and especially stationers serving the trade in paperwork here. Other examples often lacked the basement bulkheads found in Philadelphia or had a different rhythm of front doors and windows, and after mid-century cast iron might replace the large marble or granite blocks that opened the ground story - in both cases probably pieces produced as standard, commodified elements of commercial building shipped out to various cities. This rather generic building type may well represent an international commercial vernacular, at least in Anglo-American contexts. Its functional form was of course hardly unself-conscious; it was, in fact, extremely witting, adapted quickly and well to 8 Charles Lowenstrom, New-York Pictorial Business Directory of Wall-St. (New York, 1850). 14 accommodating what would often turn out to be a fairly frequent succession of varied businesses, some taking only a floor, some breaking through party walls to neighboring spaces, some bringing customers in to see items on display, some manufacturing on site, some simply storing goods that were bought and sold from or sent to distant locations. These buildings were critical equipment in a landscape of shifting opportunities often only modestly capitalized, where tenancy of businesses seems to have been the more common situation. Where period real estate atlases indicated ownership, the names on the map were rarely coincident with the ones on the signboards. (In Boston’s downtown in the late 1880s, for example, many of the land-owners were identified as trusts of venerable old Boston families and institutional corporations vested beneath the changing retailers, even owning the sites of some of the best-known stores.9) Such key venues in various cities seem to have been held by long-standing interests that recognized their present and future value; as long as rents were stable, this arrangement may have suited many merchants, who could then dedicate nearly all their working capital for goods to resell, for raw materials, personnel, or promotion rather than tying it up longer term in real estate. This could have a decided effect on built form. Where merchants usually did not own the premises, and when they might move within a decade, their investment in an individualized architecture was understandably rare. Instead, their place within a dense commercial matrix of similarly generic buildings depended critically on applied signage, and on placing their address repeatedly before their potential customers by any other means. Their numerical address was an insistent feature of signs and of early advertising, and in period photographs an almost implausibly feverish multiplication of signboards crowded the long horizontal registers between windows, sometimes rising in 9 Comparing names of stores on signboards in 1880s streetscape images with their footprints in George W. Bromley, Atlas of the city of Boston and vicinity, Volume 1 (Philadelphia, 1889), which inscribed the names of many landowners. 15 great shaped crestings crowning a façade to prominently display a number, name, or even an icon like a hat or umbrella that cued passersby to the offerings within. This generic building form -- which one might expect in the secondary commercial network of streets where wholesale, specialized retail, and small-scale manufacturing thrived -- was also a key component of the early form of the elite retail corridor (fig. 7), although it survives less often there, for those more visible streetscapes were much Fig. 7. Detail of 500-block of Chestnut Street, north side, in 1857, from Baxter & Neff, prospectus for "Baxter's Panorama and Business Directory of Philadelphia," 1857 (Library Company of Philadelphia). more susceptible to decades of incremental but unceasing and ultimately sweeping change. They were, however, also frequent subjects of period images of many sorts that help us to see the form of this commercial corridor in its earlier form. Long Views Isolated period glimpses and oblique vistas are offered in old photographs, in early forms of illustrated advertising, and in occasional survivals that, alongside detailed period maps, allow us to assemble and reconstruct a sense of that once-new city. Our most effective period portrait, however, lies in a particular, if rather scarce species of print that offered long views of successive block-faces in near elevation, such as those 16 seen in figures 1, 2, and 7, above. These extended street-views serve as a particularly rich record of the extremely changeful business corridors of the city, capturing their period appearance and continuities like no other, offering virtual eye-level surrogates for movement down the street. Usually produced as lithographs or wood engravings, these reproduced streetscapes in strips that were sometimes just a few inches high, but in series they could amount to several feet across, tracking multiple blocks along major streets. They were created for a range of reasons, and in a range of forms. Some of the earlier Continental European examples from the 1820s to 1840s -- showing the Grand Boulevards of Paris (fig. 8), Unter den Linden in Berlin, and the Nevsky Prospekt in St. Petersburg -- appear to have been undertaken by entrepreneurial artists for sale as Fig. 8. Excerpt of streetscape of the Boulevard des Italiens, from by E. Renard and A. Provost, 1845, as republished in Edmond Auguste Texier, Tableau de Paris, 2 vols. (Paris, 1852-53) (Courtesy of Special Collections, Bryn Mawr College Libraries). touristic keepsakes of vaunted destinations. The identification of shops, theaters, or cafés in these generally appears to have been included to underscore the desirability of the sites and verisimilitude of the image, rather than a matter of paid placements. Most of the Anglo-American examples, though, were made primarily and quite specifically to promote the businesses depicted and identified, and more specifically the ones that 17 paid for this. Sometimes called “pictorial“ or “panoramic” business directories, these were vehicles for disseminating an awareness of commercial locations, prominently displaying addresses and identifying offerings, and depicting distinctive aspects of their situation relative to landmarks and intersections, capturing distinctions embodied in their architecture and their signage. These long street-view sets effectively served as did the facades crested with the big number or the occasional individualized stone front on the street -- with stores primping for identifiability within the ensemble, if in microcosm, on paper. In the bestdocumented cases, one finds that an enterprising artist would draw a promising block and then canvass the businesses depicted there for paying subscribers, who would have their buildings identified in the published street-view and sometimes also in a grid of business-card replicas or a letterset directory. The facades of non-subscribers would lack these identifying elements. This specific scheme seems to have been first exploited at a large scale in London in the street views issued by John Tallis from 1838 to 1847 (fig. 9), and the form soon Fig. 9. Part of Fleet Street, from John Tallis, Tallis's London Street Views (London, 1838-40). plate 15. found its way to Bristol, Bath, Manchester, and Dublin. Tallis intended to bring this to New York City, sending his nephew Alfred, only to discover that the short-lived firm of Jones, Newman, and Ewbank had already published their Illuminated Pictorial Directory 18 of Broadway in 1848 on much the same scheme.10 Other New York streets, such as William Street, Fulton Street, Maiden Lane, and Wall Street, followed in 1849 and 1850, Chestnut Street in Philadelphia in 1851, and two key Boston streets in 1853. The Bostonian set adopted a different operative model, identifying stores more comprehensively in double-page spreads as an added attraction for subscribers to Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion -- a publication venue par excellence for the bourgeois consumers of precisely this high-end retail territory in several American downtowns; the opening of a new silverware and jewelry store, carpet warehouse, or a lace and bonnet shop could be the subject of an illustrated story there. The long street-view series that appeared in several cities vividly captured both the seriality of experience and the successive typologies that defined these corridors of commerce. The preeminence of such elite corridors over nearby business streets was often borrowed from elite residential venues that preceded their functional reassignment, and vestiges of that history were often visibly inscribed in the appearance of repurposed buildings glimpsed in these long views. Even as ground-story portions of facades were almost universally removed and replaced by maximized glazing and multiplied doorways at grade, many stores preserved their old dormered, double-pitched roof, residentially-scaled upper windows, and limited extent in height -- rarely more than 3.5 stories -- and depth -- rarely without a sizable rear yard (see fig. 4, above). But these changes also required removing the front steps that had led to an elaborated doorway in most middle- and upper class residences, and dropping the whole first floor to grade-level. Often, older fashionable residences had been set back a few feet or more from the sidewalk, which left their facade recessed after conversion to a store, while newly built or extended commercial buildings next door almost always toed the building line, pushing right up to the pedestrian. See Peter Jackson, John Tallis’s London Street Views, 1838-1840 (London, 1969), which reproduces the plates and also provides valuable research on the publisher and the series in two introductory articles. 19 10 This pattern of commercial adaptation is especially notable in an early set of views of eight continuous blocks of Chestnut Street in Philadelphia from 1851. Toward the older city center, near Third Street, were some purpose-built high-end shops from decades earlier, marked by large-scale yet geometrically simplified windows beyond the first floor that reflected multiple-story commercial spaces. Further west from there, one mainly observes the vestiges of older elite residences -- some of them wide individual mansions and some narrower townhouses built in repetitive rows -- that were altered for business uses in a tide that successively tracked outward from the old commercial core nearer the Delaware River waterfront. Within a decade, though (fig. 10), there was evidence of two other tides: first, replacement of some by those taller but generic, purpose-built commercial buildings, simple arrays of repeated oblong windows fronting deep open floor spaces; and second, greater investment in distinctive facade designs and materials, meant by some owners to call their buildings out amid more prosaic streetscapes. The first to do the latter were larger structures -- theaters, grand hotels, and banks -- often embellished with carved stone or cast iron to more assertively invoke the cultural benediction of recognized languages of historical style. But early store buildings built in repetitive series were also sometimes elaborated in this way. Built speculatively for leasing to individual merchants, they would proffer a degree of shared visual distinction. These could range from pairs with repeated arched or pilastered forms or tinted stucco surfaces -- in designs that would embrace their essential verticality and mark them in an otherwise planar and rectilinear brick streetscape -- to block-long fronts that reiterated unifying effects, such as repeated window heads treated as Gothic labels, long series of pilasters or columns joining upper stories, or embracing cornices and identical doorway designs scanning across long horizontal frontages. 20 In these large structures, component two- or three-bay stores might bear a collective identification as part of the "Washington Stores," "Park Row Stores," "Touro Block," or "Grigg Block." Large period lithographs of such blocks sometimes celebrated their extent and form and identified their initial tenants, apparently touting that mutually beneficial connection for landlord and tenant, in what might be thought of as a collective trade card.11 Ambitions on the part of landowners must have been expected to reward their investment in this degree of architectural distinction because of the expected appeal to individual merchants, for such arrangements would memorably situate them within a larger and well-known urban element rather than leave them to the relative anonymity of an address locating them within the grid. Such unifying treatment usually relied on polite architectural language, employing stone and stylistic detail to identify the whole broadly with a character of bourgeois gentility as set off from more prosaic and expedient usages. Difference, however, was soon increasingly inscribed in individualized architectural form. Images of American streetscapes from about the mid-50s on suggest that a sense of visual competition on the principal streets drove many high-end retailers to more frequently engage architects to design single buildings meant to stand out on these streets, just as each would on such paper surrogates (fig. 10). For these businesses, elaborated, singular facades could be more assertive essays in place-marking, in class-connoting elaboration, and in fashionable currency played out against the foil of their neighbors -- with stone against brick, light tones against darker ones, rounded against rectilinear, taller against shorter. Businesses in buildings individualized in stone also implicitly made a promise of solidity and persistence, having invested beyond a signboard, letterhead, and a steady rent to mark themselves amid what otherwise might have seemed a treacherous landscape of shifting opportunities and opportunists. Proprietors of such a business would have seen their advantage in owning their property outright (or on longer-term leases) in order to control their location and distinguish their quarters as they rarely had earlier. And 11 4 litho cites. 21 images of that facade would appear wherever they could build visual recognition on paper, from their correspondence and bill-heads to other still-rare venues for such illustrated self-promotion such as trade cards and street-view series. Fig. 10a. 700-block Chestnut Street, south side, 1851, from Julio H. Rae, Rae's Philadelphia Pictorial Directory and Panoramic Advertiser (Philadelphia, 1851), composite of pls. 11 and 12 (Philadelphia Athenaeum). Fig. 10b. "Chestnut Street from Seventh to Eighth. (South Side)," 1861, from Dewitt C. Baxter, "Baxter's Panoramic Business Directory of Philadelphia," first series (1857-61) (Historical Society of Pennsylvania). Even as the operative rules of full-lot coverage, blind party walls, and frontal selfidentification still pertained, there was also an architectural transformation inside, something portrayed in later trade cards, in magazines like Gleason’s Pictorial, in occasional photographs, and in fire insurance surveys. They show lavish interiors (fig. 11), opened to large skylights and surrounded by balustraded balconies beckoning customers to upper levels. Wall and ceiling surfaces were elaborated far beyond the old prosaic standard with what might best be described as baroque plasterwork and rich materials that matched the finest domestic parlors of their clientele, identifying with the same haute-bourgeois material aspirations and anxieties. Few touted their understanding of this visually competitive environment more strongly than Henry Shaw, the entrepreneur behind Dublin's New City Pictorial Directory (1850), which included a set of 76 street-views. Writing promotionally when he first issued 22 Fig. 11. Max Rosenthal, "Interior View L. J. Levy & Co's Dry Goods Store, Chestnut St. Phila.." [809-11 Chestnut Street], c.1857 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Bc 38 L 668 [W186]). his directory, Shaw explained that the merchant or trader will now . . . have the opportunity of . . . bringing his establishment prominently before the public eye. The improvements in Shop Architecture recently effected can here be introduced with advantage, while the superiority of this [visual] mode of publicity to a mere literary [textual] advertisement needs no comment."12 Those improvements in shop architecture were not so dramatic in Shaw's views of Dublin's streets, but in the succeeding decade they would become far more noticeable, at least in images of commercial streets in Philadelphia and New York, Boston and New Orleans. In those cities, the 1850s seem to have brought a marked increase in a more insistently particularized and elaborated commercial architecture seen in many of the street-view sets of that and the subsequent decades. Leading architects of those decades rose to the challenge to individualize, even in the limited scope of 20 or 30 feet of frontage. But therein lies another chapter, one that climaxed in the 1870s and 1880s, and yet a third quickly followed, this operating at new scales that ushered in a far more sweeping 12 Commercial Journal & Family Herald (Dublin), 17 March 1850. 23 transformation beginning in the late 1880s. Vertically, this new scale was made possible by new building technologies, but it was often propelled by a growing hunger for downtown office space, a demand frequently served though real estate investment by financial companies -- whose own identifying architectural imagery usually overshadowed that of the shops below. Meanwhile, department stores claimed extended horizontal footprints within the central business district, claiming the sites of many smaller older shops. Ever larger business buildings and then the hunger of the car would continue to devour much of the remaining mid-nineteenth-century streetscape in the twentieth, but visual evidence such as that broached here offers a rare window onto an earlier downtown streetscape largely lost to subsequent development. And that once-new downtown embodied a shaping prologue to the commercial landscapes that would follow. <end> 24