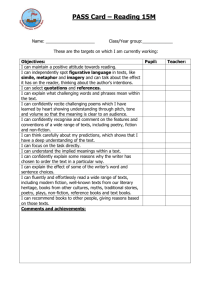

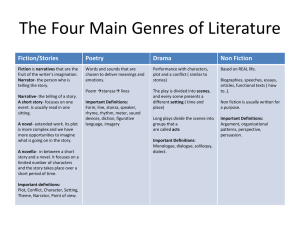

Massachusetts English Language Arts Curriculum Framework

advertisement