Title: Symptom Burden in the Chronically Ill Homebound

advertisement

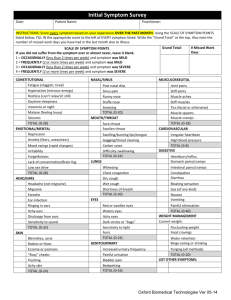

Title: Symptom Burden in the Chronically Ill Homebound Authors: Ania Wajnberg, MD,1 Meng Zhang, MD,1 Kristofer L Smith, MD, MPP1 Katherine Ornstein MPH,1,2 Theresa Soriano MD MPH1 1 Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors Program, Division of General Internal Medicine, The Samuel Bronfman Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY; 2 Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY Corresponding Author: Ania Wajnberg, MD One Gustave L. Levy Place Box 1216 New York, NY 10029 Phone: 212-241-4141 Fax: 212-426-5108 Email: ania.wajnberg@mountsinai.org Funding sources: Chiang Family Foundation Prior Presentations: Palliative Symptom Burden in an Urban Homebound Population. Annual Assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, March 2010. Illness and Palliative Symptom Burden in the Homebound Elderly. Presidential Poster Session, Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society, Orlando, Florida, May 2010. Background: Elderly patients living with multiple chronic medical conditions pose a disproportionate burden on our society and the US health care system.i The prevalence of chronic conditions rises with ageii and by 2030, almost 20% of the US population will be greater than 65 years of age with an increase by over 50% in those greater than 85 years of age.iii A large portion of these elderly, chronically ill patients suffer from significant functional impairment that leaves them homebound and unable to access routine medical care. The number of these homebound seniors already exceeds two million, and is expected to reach over three million in the next ten years.iv Homebound patients often have conditions associated with substantial symptom burden such as dementia, congestive heart failure, depression, and cancer.v Short term mortality rates are high - nearly one in five die each year.viviiviiiix Furthermore, issues such as poverty, poor health literacy, and limited social support complicate timely access to quality care.v-ix Even those who are able to access outpatient care may not be able to find appropriately trained and experienced providers to manage their complex primary care needs and substantial symptom burden. It has been increasingly recognized that high quality outpatient care includes palliative care.x Symptom management, skilled communication, and psychosocial and spiritual support offered by palliative care specialists, however, continue to be mostly available in the inpatient or outpatient hospice setting. This is despite evidence showing that in home palliative care for the vulnerable elderly increases patient satisfaction and cuts costs.xi The current reimbursement incentives and the lack of sufficient number of palliative trained providers are a few of the factors contributing to this gap. Given these realities, it is essential to identify patient cohorts with high symptom burden who would benefit from the limited palliative care resources available in the outpatient setting. To document the degree of symptom burden in a chronically-ill homebound population that may benefit from in-home palliative care, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of patients newly enrolled in an urban home-based primary care (HBPC) program. Methods Setting This study was conducted at the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors (MSVD) program, a large HBPC program based in New York City. Previously described in detail,xii the program employs 14 physicians, 2 nurse practitioners (NP), 2 nurses, 3 social workers, and 4 clerical staff to serve over 1000 homebound patients annually. Patients are referred from a variety of sources including the inpatient setting, outpatient clinics, community agencies, word of mouth, and nursing agencies. A comprehensive initial visit is performed for all newly enrolled patients by a primary care physician (PCP) during which standardized assessments are performed measuring functional status, cognition, and symptom burden. PCPs visit patients on average once every 2 months, and physicians are able to make urgent home visits if clinical need arises. Patients and their families are able to contact a physician 24 hours/day, 7 days/week by telephone. High priority is placed on patient quality of life, comfort, and minimizing unnecessary hospitalizations. Subjects Between September 2008 and February 2010, data was collected on all patients newly enrolled in the MSVD program. Eligibility criteria for the MSVD program includes living in Manhattan above 59th street, age >18 years, and meeting the Medicare homebound definition - able to leave home only with great difficulty and for absences that are infrequent or of short duration. Patients are enrolled regardless of insurance status, co-morbidities, or cognitive status. This study protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Measures The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) was administered to all study participants. The ESAS consists of ten visual analogue scales scored from 0, indicating no symptoms, to 10, the worst possible symptom burden. The symptoms assessed include pain, tiredness, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, well-being, shortness of breath, and other (to be filled out by the provider).xiii The ESAS tool was chosen as it is validated in a number of care settingsxiv, and is validated for both patient and/or caregiver report. Severe symptom burden is defined by a score of >6 on one or more individual symptoms. Moderate symptom burden is defined by a score of >3 and <7 on one or more individual symptoms, mild symptom burden is defined as a score of 1-3 on one or more individual symptoms, and a score of 0 indicates no symptoms.xv Data Collection Patients’ PCPs administered the ESAS as a routine part of the comprehensive initial home visit. ESAS was completed either by the patient alone, caregiver alone, or caregiver assisted. Data on patient demographics, co-morbidities, Palliative Performance Scale score (PPS), Karnofsky performance status score (KPS), and functional status (activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL)) were also collected at the initial visit by the MSVD provider. Analysis Patient ESAS scores were stratified into none, mild, moderate, or severe symptom burden (defined above). Investigators completed bivariate analyses looking for associations between ESAS score and disease state using Pearson’s chi square test. All analyses were completed using STATA. RESULTS Between September 2008 and February 2010, 475 patients were newly enrolled in the MSVD program. Providers recorded ESAS scores for 318 patients (67%). Reasons for missing data included: 56 patients/caregivers (12%) were unable to complete the survey, 16 (3%) refused, and 82 (17%) unknown. Among those with ESAS scores, the majority was over 80 years of age (68%) and female (75%). Thirty six percent of these patients were white, 22% were black, and 32% were Hispanic/Latino. A substantial portion (43%) had Medicaid and lived alone (32%). Disease burden was considerable-- 49% had dementia, 26% had depression, 18% had congestive heart failure, 13% had cancer and 4% had COPD. 91% of patients required assistance with one or more ADLs and 99% required assistance with one or more IADLs. PPS and KPS mean score was XX and XX. For these measures, there were no statistically significant differences between the patients for whom ESAS data was collected and those who were missing. The most commonly reported symptoms were loss of appetite, lack of well-being, tiredness, and pain (Table 1). Almost half (43%) reported severe burden on one or more symptoms. Another 33% had at least one moderately troubling symptom and only 14% reported no symptoms. The symptoms which had the highest average score were depression, pain, appetite, and shortness of breath. Patients reported difficulty with a median of 3 different symptoms at baseline, 2 of which were moderate/severe. Those patients with severe symptom burden were statistically significantly more likely to suffer cancer (p<0.01) or depression (p<0.01) and significantly less likely to suffer from dementia (p<0.01). There was no statistically significant difference in ESAS score severity between patients with and without congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes or stroke. DISCUSSION This study demonstrated a significant palliative symptom burden in a previously uninvestigated population of elderly homebound with multiple co morbidities. In our cohort, patients commonly suffered from loss of appetite, lack of well-being, tiredness and pain. Their most severe symptoms were depression, pain, appetite, and shortness of breath. Cancer and depression were associated with higher symptom scores, whereas dementia was associated with lower symptom scores. These findings show that symptom burden in the chronically ill homebound is similar in severity and scope to patients referred to hospice or to hospitalized cancer patients. In 2003, Potter et al found that patients referred to hospice had high symptom burden (7.21 median ESAS score) with the most common symptoms being pain (64%), anorexia (34%), and constipation (32%).xvi Similarly, in cancer patients attending an outpatient palliative care clinic, the most frequent and also most severe self-reported symptoms were fatigue (77%, median ESAS score 7), pain (75%, median ESAS score 7), and lack of appetite (66%, median ESAS 5).xvii The high symptom burden in the homebound population underscores the importance of symptom recognition and management for those with advanced illness from chronic medical conditions. This should be considered as the United States health care system restructures itself to meet the needs of our most vulnerable seniors. Finding new ways to address their health care needs is a growing imperative as the number of homebound patients will increase by millions in the coming decades. Furthermore, the cost of caring for the elderly with multiple chronic medical problems is becoming an increasing burden on the health care system, with 10% of Medicare beneficiaries driving approximately two thirds of Medicare costs.xviii Some of this high cost may be driven by emergency department and hospital use by patients seeking relief for untreated symptoms. With 76% of patients in our cohort reporting moderate to severe symptom burden, the need for the incorporation of palliative care into models of care for the homebound is highlighted. The integration of palliative care into primary care for the chronically ill should be applied in order to lessen symptom burden and alleviate patient suffering. Internal medicine training largely centers on chronic disease management, but little focus has been placed on concurrent treatment of symptom burden. Other barriers to effective palliative care for this population includes program design with adequate staffing to effectively use physicians, nurses, social workers, hospice, support staff, and case management; provide regular and urgent visits, and to be accessible to patients 24 hours/day.xix Payment incentives must be reworked in order to more effectively incentivize the primary care work force to provide for the symptom burden of the chronically ill elderly. LIMITATIONS: Although ESAS has been well validated in the inpatient setting, less data is available on its use in homebound patients as well as in outpatient demented patients. The 82 missing ESAS scores may have led to selection bias. The inverse association observed between dementia and symptom burden may be secondary to reporting bias, with demented patients less able to report subjective symptoms to caregivers or to PCPs. Patients with advanced dementia pose a particular challenge in terms of symptom assessment and recognition and there are other scales that may be more appropriate in this population. Although ESAS allowed for better symptom identification, it as yet remains unclear whether performing the ESAS on all new patients led to increased PCP interventions or improved symptom treatment. Additionally the data collection plan of using the patient’s PCP to assess symptom burden meant that much of the data was collected by different providers. Our findings may have been different had the data been collected by a single researcher, rather than the 14 physicians who are a part of the MSVD program. CONCLUSION Prior studies have shown that palliative care services increase patient satisfaction and wellbeing and we believe this can be extended into the community. Our study demonstrates that in this population of chronically ill homebound adults most of whom do not meet hospice criteria, symptom burden is a serious problem that needs to be addressed alongside their primary and specialty care needs. Timely symptom burden assessment and aggressive intervention may prevent unnecessary health care utilization, may improve patients’ quality of life and reduce caregiver burden. Further study will investigate whether ESAS scores in this population are predictive of hospitalization and mortality and whether follow-up ESAS assessments serve as a useful tool to monitor symptom burden over time. i Wolff JL, Starfield B, et al. Prevalence, Expenditures, and Complications of Multiple Chronic conditions in the Elderly. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002; 162: 2269-2276. ii Wu S, Green A. Projection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost Inflation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health. October 2000. iii U.S. Census Bureau. (2004). U.S. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin. Retrieved June 10, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/. iv Qiu WQ, Dean M, Liu T, George L, Gann M, Cohen J, Bruce ML. Physical and mental health of homebound older adults: an overlooked population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Dec;58(12):2423-8. v Kellogg FR, Brickner PW. Long-term home healthcare for the impoverished frail homebound aged: A twentyseven-year experience. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1002-11. vi Gammel JD. Medical house call program: Extending frail elderly medical care into the home. J Oncol Manag. 2005;14:39-46. vii Mor V, Zinn J, Gozalo P, Feng Z, Intrator O, Grabowski DC. Prospects for transferring nursing home residents to the community. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:1762-71. viii Agar M, Currow DC, Shelby-James TM, Plummer J, Sanderson C, Abernethy AP. Preference for place of care and place of death in palliative care: Are these different questions? Palliative Medicine. 2008;22:787-795. ix Townsend J, Frank AO, Fermont D, et al. Terminal cancer care and patients' preference for place of death: A prospective study. BMJ. 1990;301:415-7. x Meier DE, Beresford L. Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008 Jul;11(6):82328. xi Brumley R, Enguidanos S, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007. ;55: 993-1000. xii Smith KL, Ornstein K, Soriano T, Muller D, Boal J. A multidisciplinary program for delivering primary care to the underserved urban homebound: looking back, moving forward. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1283-1289. xiii Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991; 7: 6–9. xiv Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000 May 1;88(9):2164-71. xv Selby D, Cascella, A, et al. A single Set of Numerical Cutpoints to Define Moderate and Severe Symptoms for the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010; 39(2): 241-249. xvi Potter J, Hami F et al. Symptoms in 400 patients referred to palliative care services: prevalence and patternsPalliat Med. 2003 Jun;17(4):310-4. xvii Riechelmann RP, Krzyzanowska MK, et al. .Symptom and medication profiles among cancer patients attending a palliative care clinic. Support Care Cancer. 2007 Dec;15(12):1407-12. xviii Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW, et al. Prescription Drugs and the Changing Concentration of Health Care Expenditures. Health Affairs. 2007; 26(1):249-57. xix Meier DE, Beresford L. Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008 Jul;11(6):823-28. Table 1. Characteristics of Study Sample (N=318) Gender Female Male Ethnicity White Latino Black Asian Other Number (%) 238 (75) 80 (25) 115 (36) 101 (32) 70 (22) 7 (2) 7 (2) Language English Spanish 205 (64) 78 (25) Other 15 (5) Unknown 20 (6) Diagnosis Dementia Congestive Heart Failure Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Depression Cancer Activities of Daily Living (0-16) 0-3 4-7 8-11 12-15 16 Missing Insurance Medicaid Non Medicaid Age <60 60-69 70-79 80-89 90-99 >100 Living Situation Alone With Family Member With Paid Caregiver With Family + Paid Caregiver Unknown Number (%) 136 (43) 182 (57) Independent Activities of Daily Living (0-8) 7-8 5-6 3-4 0-2 Missing (8=Independent 0 = Totally dependent) 10 (3) 29 (9) 60 (19) 107 (34) 99 (31) 13 (4) 101 (32) 121 (38) 58 (18) 20 (6) 18 (6) 155 (49) 56 (18) 12 (4) 83 (26) 42 (13) (0 = Independent 16 = Totally dependent) 82 (26) 51 (16) 47 (15) 63 (20) 60 (19) 15 (5) 9 (3) 26 (8) 57 (18) 190 (60) 36 (11) Table 2. Symptom Burden as measured by the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (N=318) Symptom Percent with Symptom Mean Score Pain 47% 5.09 Tiredness 49% 5.79 Nausea 10% 4.27 Depression 33% 5.27 Anxiety 27% 5.32 Drowsiness 37% 5.18 Loss of Appetite 53% 4.77 Feeling of Well-being 48% 5.24 Shortness of breath 27% 4.91 Table 3. Association between symptom score and co-morbidities Disease High symptom burden - High symptom Percent of patients with burden - Percent of disease patients without P value disease Cancer 8% (24) 5% (18) 0.09 Depression 19% (62) 7% (21) <0.01 Dementia 15% (49) 33% (106) <0.01 Congestive heart failure 10% (31) 8% (25) 0.08 Chronic obstructive 7% (21) 4% (12) 0.02 pulmonary disease