Cranberry Sustainable Resource Management Plan

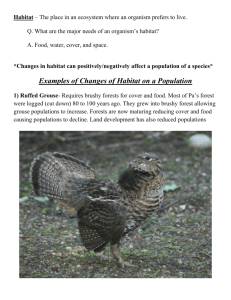

advertisement