Municipal early years plan framework (Word

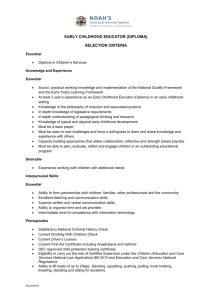

advertisement