Hydrocarbon - Mansfield Gas Well Awareness

advertisement

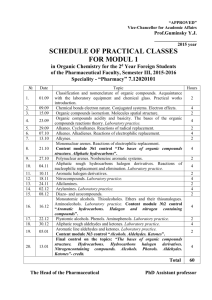

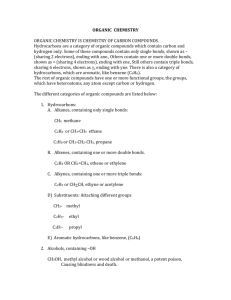

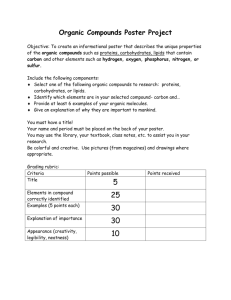

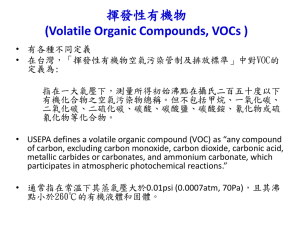

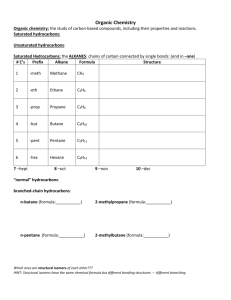

Welcome to Wikipedia Hydrocarbon From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Ball-and-stick model of the methane molecule, CH4. Methane is part of a homologous series known as the alkanes, which contain single bonds only. In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon.[1] Hydrocarbons from which one hydrogen atom has been removed are functional groups, called hydrocarbyls.[2] Aromatic hydrocarbons (arenes), alkanes, alkenes, cycloalkanes and alkyne-based compounds are different types of hydrocarbons. The majority of hydrocarbons found on Earth naturally occur in crude oil, where decomposed organic matter provides an abundance of carbon and hydrogen which, when bonded, can catenate to form seemingly limitless chains.[3][4] Contents [hide] 1 Types of hydrocarbons o 1.1 General properties o 1.2 Simple hydrocarbons and their variations 2 Usage 3 Poisoning 4 Reactions o 4.1 Substitution Reaction o 4.2 Addition Reaction o 4.3 Combustion 4.3.1 Petroleum 4.3.2 Bioremediation 5 See also 6 References 7 Bibliography 8 External links Types of hydrocarbons[edit] The classifications for hydrocarbons, defined by IUPAC nomenclature of organic chemistry are as follows: 1. Saturated hydrocarbons (alkanes) are the simplest of the hydrocarbon species. They are composed entirely of single bonds and are saturated with hydrogen. The general formula for saturated hydrocarbons is CnH2n+2 (assuming non-cyclic structures).[5] Saturated hydrocarbons are the basis of petroleum fuels and are found as either linear or branched species. Substitution reaction is their characteristics property (like chlorination reaction to form chloroform). Hydrocarbons with the same molecular formula but different structural formulae are called structural isomers.[6] As given in the example of 3-methylhexane and its higher homologues, branched hydrocarbons can be chiral.[7] Chiral saturated hydrocarbons constitute the side chains of biomolecules such as chlorophyll and tocopherol.[8] 2. Unsaturated hydrocarbons have one or more double or triple bonds between carbon atoms. Those with double bond are called alkenes. Those with one double bond have the formula CnH2n (assuming non-cyclic structures).[9] Those containing triple bonds are called alkynes, with general formula CnH2n-2.[10] 3. Cycloalkanes are hydrocarbons containing one or more carbon rings to which hydrogen atoms are attached. The general formula for a saturated hydrocarbon containing one ring is CnH2n.[6] 4. Aromatic hydrocarbons, also known as arenes, are hydrocarbons that have at least one aromatic ring. Hydrocarbons can be gases (e.g. methane and propane), liquids (e.g. hexane and benzene), waxes or low melting solids (e.g. paraffin wax and naphthalene) or polymers (e.g. polyethylene, polypropylene and polystyrene). General properties[edit] Because of differences in molecular structure, the empirical formula remains different between hydrocarbons; in linear, or "straight-run" alkanes, alkenes and alkynes, the amount of bonded hydrogen lessens in alkenes and alkynes due to the "self-bonding" or catenation of carbon preventing entire saturation of the hydrocarbon by the formation of double or triple bonds. This inherent ability of hydrocarbons to bond to themselves is known as catenation, and allows hydrocarbon to form more complex molecules, such as cyclohexane, and in rarer cases, arenes such as benzene. This ability comes from the fact that the bond character between carbon atoms is entirely non-polar, in that the distribution of electrons between the two elements is somewhat even due to the same electronegativity values of the elements (~0.30), and does not result in the formation of an electrophile. Generally, with catenation comes the loss of the total amount of bonded hydrocarbons and an increase in the amount of energy required for bond cleavage due to strain exerted upon the molecule;in molecules such as cyclohexane, this is referred to as ring strain, and occurs due to the "destabilized" spatial electron configuration of the atom. In simple chemistry, as per valence bond theory, the carbon atom must follow the "4-hydrogen rule", which states that the maximum number of atoms available to bond with carbon is equal to the number of electrons that are attracted into the outer shell of carbon. In terms of shells, carbon consists of an incomplete outer shell, which comprises 4 electrons, and thus has 4 electrons available for covalent or dative bonding. Hydrocarbons are hydrophobic like lipids. Some hydrocarbons also are abundant in the solar system. Lakes of liquid methane and ethane have been found on Titan, Saturn's largest moon, confirmed by the Cassini-Huygens Mission.[11] Hydrocarbons are also abundant in nebulae forming polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) compounds.[12] Simple hydrocarbons and their variations[edit] Number of Alkane (single carbon bond) atoms Alkene (double bond) Alkyne (triple bond) Cycloalkane Alkadiene 1 Methane - - - - 2 Ethane Ethene (ethylene) Ethyne (acetylene) – – 3 Propane Propene (propylene) Propyne (methylacetylene) Cyclopropane Propadiene (allene) 4 Butane Butene (butylene) Butyne Cyclobutane Butadiene 5 Pentane Pentene Pentyne Cyclopentane Pentadiene (piperylene) 6 Hexane Hexene Hexyne Cyclohexane Hexadiene 7 Heptane Heptene Heptyne Cycloheptane Heptadiene 8 Octane Octene Octyne Cyclooctane Octadiene 9 Nonane Nonene Nonyne Cyclononane Nonadiene 10 Decane Decene Decyne Cyclodecane Decadiene Usage[edit] Oil refineries are one way hydrocarbons are processed for use. Crude oil is processed in several stages to form desired hydrocarbons, used as fuel and in other products. Hydrocarbons are a primary energy source for current civilizations. The predominant use of hydrocarbons is as a combustible fuel source. In their solid form, hydrocarbons take the form of asphalt (bitumen).[13] Mixtures of volatile hydrocarbons are now used in preference to the chlorofluorocarbons as a propellant for aerosol sprays, due to chlorofluorocarbon's impact on the ozone layer. Methane [1C] and ethane [2C] are gaseous at ambient temperatures and cannot be readily liquefied by pressure alone. Propane [3C] is however easily liquefied, and exists in 'propane bottles' mostly as a liquid. Butane [4C] is so easily liquefied that it provides a safe, volatile fuel for small pocket lighters. Pentane [5C] is a clear liquid at room temperature, commonly used in chemistry and industry as a powerful nearly odorless solvent of waxes and high molecular weight organic compounds, including greases. Hexane [6C] is also a widely used non-polar, nonaromatic solvent, as well as a significant fraction of common gasoline. The [6C] through [10C] alkanes, alkenes and isomeric cycloalkanes are the top components of gasoline, naphtha, jet fuel and specialized industrial solvent mixtures. With the progressive addition of carbon units, the simple non-ring structured hydrocarbons have higher viscosities, lubricating indices, boiling points, solidification temperatures, and deeper color. At the opposite extreme from [1C] methane lie the heavy tars that remain as the lowest fraction in a crude oil refining retort. They are collected and widely utilized as roofing compounds, pavement composition, wood preservatives (the creosote series) and as extremely high viscosity shear-resisting liquids. Poisoning[edit] Hydrocarbon poisoning such as that of benzene and petroleum usually occurs accidentally by inhalation or ingestion of these cytotoxic chemical compounds. Intravenous or subcutaneous injection of petroleum compounds with intent of suicide or abuse is an extraordinary event that can result in local damage or systemic toxicity such as tissue necrosis, abscess formation, respiratory system failure and partial damage to the kidneys, the brain and the nervous system. Moaddab and Eskandarlou report a case of chest wall necrosis and empyema resulting from attempting suicide by injection of petroleum into the pleural cavity.[14] Reactions[edit] There are three main types of reactions : Substitution Reaction Addition Reaction Combustion Substitution Reaction[edit] Substitution reaction only occur in saturated hydrocarbons (single carbon-carbon bonds). In this reaction, an alkane reacts with a chlorine molecule. One of the chlorine atoms displace an hydrogen atom. This forms hydrochloride acid as well as the hydrocarbon with one chlorine. e.g. CH4 + Cl2 →CH3Cl + HCl e.g. CH3Cl3 + Cl2 →CH2Cl2 + HCl All the way until CCl4 (Carbon tetrachloride) e.g. C2H6 + Cl2 →C2H5Cl1 + HCl e.g. C2H4Cl2 + Cl2 →C2H4Cl3 + HCl All the way until C2Cl4 (DiCarbon tetrachloride) Addition Reaction[edit] Addition reactions involve alkenes and alkynes. In this reaction a halogen molecule breaks the double or triple bond in the hydrocarbon and forms a bond. Combustion[edit] Container of ethanol vapour mixed with air, undergoing rapid combustion Main article: Combustion Hydrocarbons are currently the main source of the world’s electric energy and heat sources (such as home heating) because of the energy produced when burnt.[15] Often this energy is used directly as heat such as in home heaters, which use either petroleum or natural gas. The hydrocarbon is burnt and the heat is used to heat water, which is then circulated. A similar principle is used to create electric energy in power plants. Common properties of hydrocarbons are the facts that they produce steam, carbon dioxide and heat during combustion and that oxygen is required for combustion to take place. The simplest hydrocarbon, methane, burns as follows: CH4 + 2 O2 → 2 H2O + CO2 + Energy In inadequate supply of air, CO gas and water vapour are formed: 2 CH4 + 3 O2 → 2CO + 4H2O Another example of this reaction is propane: C3H8 + 5 O2 → 4 H2O + 3 CO2 + Energy CnH2n+2 + (3n+1)/2 O2 → (n+1) H2O + n CO2 + Energy Burning of hydrocarbons is an example of an exothermic chemical reaction. Hydrocarbons can also be burned with elemental fluorine, resulting in carbon tetrafluoride and hydrogen fluoride products Petroleum[edit] Main article: Petroleum Natural oil spring in Korňa, Slovakia. Extracted hydrocarbons in a liquid form are referred to as petroleum (literally "rock oil") or mineral oil, whereas hydrocarbons in a gaseous form are referred to as natural gas. Petroleum and natural gas are found in the Earth's subsurface with the tools of petroleum geology and are a significant source of fuel and raw materials for the production of organic chemicals. The extraction of liquid hydrocarbon fuel from sedimentary basins is integral to modern energy development. Hydrocarbons are mined from oil sands and oil shale, and potentially extracted from sedimentary methane hydrates. These reserves require distillation and upgrading to produce synthetic crude and petroleum. Oil reserves in sedimentary rocks are the source of hydrocarbons for the energy, transport and petrochemical industry. Economically important hydrocarbons include fossil fuels such as coal, petroleum and natural gas, and its derivatives such as plastics, paraffin, waxes, solvents and oils. Hydrocarbons – along with NOx and sunlight – contribute to the formation of tropospheric ozone and greenhouse gases. Bioremediation[edit] Bacteria in the gabbroic layer of the ocean's crust can degrade hydrocarbons; but the extreme environment makes research difficult.[16] Other bacteria such as Lutibacterium anuloederans can also degrade hydrocarbons.[17] Mycoremediation or breaking down of hydrocarbon by mycellium and mushroom is possible.[18] See also[edit] Abiogenic petroleum origin Biohydrocarbon Carbohydrates Energy storage Fractional distillation Functional group Hydrocarbon mixtures Hydrocarbons on other planets Organically moderated and cooled reactor References[edit] 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. Jump up ^ Silberberg, 620 Jump up ^ IUPAC Goldbook hydrocarbyl groups Jump up ^ Clayden, J., Greeves, N., et al. (2001) Organic Chemistry Oxford ISBN 0-19-850346-6 p. 21 Jump up ^ McMurry, J. (2000). Organic Chemistry 5th ed. Brooks/Cole: Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-49511837-0 pp. 75–81 Jump up ^ Silderberg, 623 ^ Jump up to: a b Silderberg, 625 Jump up ^ Silderberg, 627 Jump up ^ Meierhenrich, Uwe. Amino Acids and the Asymmetry of Life. Springer, 2008. ISBN 978-3-54076885-2 Jump up ^ Silderberg, 628 Jump up ^ Silderberg, 631 Jump up ^ http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2013-364 Jump up ^ http://arxiv.org/abs/1403.1856 Jump up ^ Dan Morgan, Lecture ENVIRO 100, University of Washington, 11/5/08 Jump up ^ Eskandarlou M, Moaddab AH. Chest wall necrosis and empyema resulting from attempting suicide by injection of petroleum into the pleural cavity. Emerg Med J. 2010 Aug;27(8):616-8. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.073486. Epub 2010 Jun 17. Jump up ^ World Coal, Coal and Electricity, http://www.worldcoal.org/coal/uses-of-coal/coal-electricity/, retrieved 07/03/2012 Jump up ^ Mason OU, Nakagawa T, Rosner M, Van Nostrand JD, Zhou J, Maruyama A, Fisk MR, Giovannoni SJ. (2010). "First investigation of the microbiology of the deepest layer of ocean crust.". PLoS ONE 5 (11): e15399. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015399. PMC 2974637. PMID 21079766. Jump up ^ M.M. Yakimov, K.N. Timmis & P.N. Golyshin (2007). "Obligate oil-degrading marine bacteria". Curr. Opin. Biotech. 18 (3): 257–266. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2007.04.006. PMID 17493798. Jump up ^ Paul Stamets in Mycellium Running, Chapter 7, page 86, Mycoremediation, ISBN 9781580085793, or his TEDx video http://www.ted.com/talks/paul_stamets_on_6_ways_mushrooms_can_save_the_world?language=en Bibliography[edit] Silberberg, Martin. Chemistry: The Molecular Nature Of Matter and Change. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, 2004. ISBN 0-07-310169-9 External links[edit] Aromatic hydrocarbon From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search "Arene" redirects here. For other uses, see Arene (disambiguation). An aromatic hydrocarbon or arene[1] (or sometimes aryl hydrocarbon)[2] is a hydrocarbon with alternating double and single bonds between carbon atoms forming rings. The term 'aromatic' was assigned before the physical mechanism determining aromaticity was discovered; the term was coined as such simply because many of the compounds have a sweet or pleasant odor. The configuration of six carbon atoms in aromatic compounds is known as a benzene ring, after the simplest possible such hydrocarbon, benzene. Aromatic hydrocarbons can be monocyclic (MAH) or polycyclic (PAH). Some non-benzene-based compounds called heteroarenes, which follow Hückel's rule (for monocyclic rings: when the number of its π-electrons equals 4n+2), are also called as aromatic compounds. In these compounds, at least one carbon atom is replaced by one of the heteroatoms oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur. Examples of non-benzene compounds with aromatic properties are furan, a heterocyclic compound with a five-membered ring that includes an oxygen atom, and pyridine, a heterocyclic compound with a six-membered ring containing one nitrogen atom.[3] Contents [hide] 1 Benzene ring model 2 Arene synthesis 3 Arene reactions o 3.1 Aromatic substitution o 3.2 Coupling reactions o 3.3 Hydrogenation o 3.4 Cycloadditions 4 Benzene and derivatives of benzene 5 Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons 6 See also 7 References 8 External links Benzene ring model[edit] Benzene Main article: aromaticity Benzene, C6H6, is the simplest aromatic hydrocarbon, and it was the first one recognized. The nature of its bonding was first recognized by August Kekulé in the 19th century. Each carbon atom in the hexagonal cycle has four electrons to share. One goes to the hydrogen atom, and one each to the two neighboring carbons. This leaves one to share with one of its two neighboring carbon atoms, which is why the benzene molecule is drawn with alternating single and double bonds around the hexagon. The structure is also illustrated as a circle around the inside of the ring to show six electrons floating around in delocalized molecular orbitals the size of the ring itself. This also represents the equivalent nature of the six carbon-carbon bonds all of bond order ~1.5. This equivalency is well explained by resonance forms. The electrons are visualized as floating above and below the ring with the electromagnetic fields they generate acting to keep the ring flat. General properties: 1. 2. 3. 4. Display aromaticity. The carbon-hydrogen ratio is high. They burn with a sooty yellow flame because of the high carbon-hydrogen ratio. They undergo electrophilic substitution reactions and nucleophilic aromatic substitutions. The circle symbol for aromaticity was introduced by Sir Robert Robinson and his student James Armit in 1925[4] and popularized starting in 1959 by the Morrison & Boyd textbook on organic chemistry. The proper use of the symbol is debated; it is used to describe any cyclic pi system in some publications, or only those pi systems that obey Hückel's rule on others. Jensen[5] argues that in line with Robinson's original proposal, the use of the circle symbol should be limited to monocyclic 6 pi-electron systems. In this way the circle symbol for a 6c–6e bond can be compared to the Y symbol for a 3c–2e bond. Arene synthesis[edit] A reaction that forms an arene compound from an unsaturated or partially unsaturated cyclic precursor is simply called an aromatization. Many laboratory methods exist for the organic synthesis of arenes from non-arene precursors. Many methods rely on cycloaddition reactions. Alkyne trimerization describes the [2+2+2] cyclization of three alkynes, in the Dötz reaction an alkyne, carbon monoxide and a chromium carbene complex are the reactants.Diels-Alder reactions of alkynes with pyrone or cyclopentadienone with expulsion of carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide also form arene compounds. In Bergman cyclization the reactants are an enyne plus a hydrogen donor. Another set of methods is the aromatization of cyclohexanes and other aliphatic rings: reagents are catalysts used in hydrogenation such as platinum, palladium and nickel (reverse hydrogenation), quinones and the elements sulfur and selenium.[6] Arene reactions[edit] Arenes are reactants in many organic reactions. Aromatic substitution[edit] In aromatic substitution one substituent on the arene ring, usually hydrogen, is replaced by another substituent. The two main types are electrophilic aromatic substitution when the active reagent is an electrophile and nucleophilic aromatic substitution when the reagent is a nucleophile. In radical-nucleophilic aromatic substitution the active reagent is a radical. An example of electrophilic aromatic substitution is the nitration of salicylic acid:[7] Coupling reactions[edit] In coupling reactions a metal catalyses a coupling between two formal radical fragments. Common coupling reactions with arenes result in the formation of new carbon–carbon bonds e.g., alkylarenes, vinyl arenes, biraryls, new carbon–nitrogen bonds (anilines) or new carbon– oxygen bonds (aryloxy compounds). An example is the direct arylation of perfluorobenzenes [8] Hydrogenation[edit] Hydrogenation of arenes create saturated rings. The compound 1-naphthol is completely reduced to a mixture of decalin-ol isomers.[9] The compound resorcinol, hydrogenated with Raney nickel in presence of aqueous sodium hydroxide forms an enolate which is alkylated with methyl iodide to 2-methyl-1,3cyclohexandione:[10] Cycloadditions[edit] Cycloaddition reaction are not common. Unusual thermal Diels-Alder reactivity of arenes can be found in the Wagner-Jauregg reaction. Other photochemical cycloaddition reactions with alkenes occur through excimers. Benzene and derivatives of benzene[edit] Benzene derivatives have from one to six substituents attached to the central benzene core. Examples of benzene compounds with just one substituent are phenol, which carries a hydroxyl group, and toluene with a methyl group. When there is more than one substituent present on the ring, their spatial relationship becomes important for which the arene substitution patterns ortho, meta, and para are devised. For example, three isomers exist for cresol because the methyl group and the hydroxyl group can be placed next to each other (ortho), one position removed from each other (meta), or two positions removed from each other (para). Xylenol has two methyl groups in addition to the hydroxyl group, and, for this structure, 6 isomers exist. Representative arene compounds Toluene Ethylbenzene p-Xylene m-Xylene Mesitylene Durene 2-Phenylhexane Biphenyl Phenol Aniline Nitrobenzene Benzoic acid Aspirin Paracetamol Picric acid The arene ring has an ability to stabilize charges. This is seen in, for example, phenol (C6H5-OH), which is acidic at the hydroxyl (OH), since a charge on this oxygen (alkoxide -O–) is partially delocalized into the benzene ring. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons[edit] An illustration of typical polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Clockwise from top left: benz(e)acephenanthrylene, pyrene and dibenz(ah)anthracene. Main article: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are aromatic hydrocarbons that consist of fused aromatic rings and do not contain heteroatoms or carry substituents.[11] Naphthalene is the simplest example of a PAH. PAHs occur in oil, coal, and tar deposits, and are produced as byproducts of fuel burning (whether fossil fuel or biomass). As pollutants, they are of concern because some compounds have been identified as carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic. PAHs are also found in cooked foods. Studies have shown that high levels of PAHs are found, for example, in meat cooked at high temperatures such as grilling or barbecuing, and in smoked fish.[12][13][14] They are also found in the interstellar medium, in comets, and in meteorites and are a candidate molecule to act as a basis for the earliest forms of life. In graphene the PAH motif is extended to large 2D sheets. See also[edit] Aromatic substituents: Aryl, Aryloxy and Arenediyl Asphaltene Hydrodealkylation Simple aromatic rings References[edit] 1. 2. Jump up ^ Definition IUPAC Gold Book Link Jump up ^ Mechanisms of Activation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor by Maria Backlund, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet 3. Jump up ^ HighBeam Encyclopedia: aromatic compound 4. Jump up ^ James Wilkins Armit and Robert Robinson (1925) "Polynuclear heterocyclic aromatic types. Part II. Some anhydronium bases," Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions, 127: 1604-1618. 5. Jump up ^ William B. Jensen (April 2009) "The circle symbol for aromaticity," Journal of Chemical Education, 86(4): 423-424. 6. Jump up ^ Jerry March Advanced Organic Chemistry 3Ed., ISBN 0-471-85472-7 7. Jump up ^ Webb, K.; Seneviratne, V. (1995). "A mild oxidation of aromatic amines". Tetrahedron Letters 36 (14): 2377–2378. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)00281-G.edit 8. Jump up ^ Lafrance, M.; Rowley, C.; Woo, T.; Fagnou, K. (2006). "Catalytic intermolecular direct arylation of perfluorobenzenes.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 128 (27): 8754–8756. doi:10.1021/ja062509l. PMID 16819868.edit 9. Jump up ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 6, p.371 (1988); Vol. 51, p.103 (1971). http://orgsynth.org/orgsyn/pdfs/CV6P0371.pdf 10. Jump up ^ Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 5, p.743 (1973); Vol. 41, p.56 (1961). http://orgsynth.org/orgsyn/pdfs/CV5P0567.pdf 11. Jump up ^ Fetzer, J. C. (2000). "The Chemistry and Analysis of the Large Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons". Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds (New York: Wiley) 27 (2): 143. doi:10.1080/10406630701268255. ISBN 0-471-36354-5. 12. Jump up ^ "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons – Occurrence in foods, dietary exposure and health effects". European Commission, Scientific Committee on Food. December 4, 2002. 13. Jump up ^ Larsson, B. K.; Sahlberg, GP; Eriksson, AT; Busk, LA (1983). "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in grilled food". J Agric Food Chem. 31 (4): 867–873. doi:10.1021/jf00118a049. PMID 6352775. 14. Jump up ^ "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 1996. External links[edit] Media related to Aromatic hydrocarbons at Wikimedia Commons <img src="//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:CentralAutoLogin/start?type=1x1" alt="" title="" width="1" height="1" style="border: none; position: absolute;" /> Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Aromatic_hydrocarbon&oldid=635532825" Categories: Aromatic hydrocarbons BTEX From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search BTEX is an acronym that stands for benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes.[1] These compounds are some of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) found in petroleum derivatives such as petrol (gasoline). Toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes have harmful effects on the central nervous system. BTEX compounds are notorious due to the contamination of soil and groundwater with these compounds. Contamination typically occurs near petroleum and natural gas production sites, petrol stations, and other areas with underground storage tanks (USTs) or above-ground storage tanks (ASTs), containing gasoline or other petroleum-related products. The amount of 'Total BTEX', the sum of the concentrations of each of the constituents of BTEX, is sometimes used to aid in assessing the relative risk or seriousness at contaminated locations and the need of remediation of such sites. Naphthalene may also be included in Total BTEX analysis yielding results referred to as BTEXN. In the same way, styrene is sometimes added, making it BTEXS. See also[edit] Alkylation BTX (chemistry) Friedel–Crafts reaction Hydrodealkylation References[edit] 1. Jump up ^ "BTEX Definition Page". USGS. December 14, 2006. <img src="//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:CentralAutoLogin/start?type=1x1" alt="" title="" width="1" height="1" style="border: none; position: absolute;" /> Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BTEX&oldid=643330670" Categories: Aromatic compounds Volatile organic compound From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are organic chemicals that have a high vapor pressure at ordinary room temperature. Their high vapor pressure results from a low boiling point, which causes large numbers of molecules to evaporate or sublimate from the liquid or solid form of the compound and enter the surrounding air. For example, formaldehyde, which evaporates from paint, has a boiling point of only –19 °C (–2 °F). VOCs are numerous, varied, and ubiquitous. They include both human-made and naturally occurring chemical compounds. Most scents or odours are of VOCs. VOCs play an important role in communication between plants, [1] and messages from plants to animals. Some VOCs are dangerous to human health or cause harm to the environment. Anthropogenic VOCs are regulated by law, especially indoors, where concentrations are the highest. Harmful VOCs typically are not acutely toxic, but have compounding long-term health effects. Because the concentrations are usually low and the symptoms slow to develop, research into VOCs and their effects is difficult. Contents [hide] 1 Definitions o 1.1 Canada o 1.2 European Union o 1.3 US 2 Biologically generated VOCs 3 Anthropogenic sources o 3.1 Specific components 3.1.1 Paints and coatings 3.1.2 Chlorofluorocarbons and chlorocarbons 3.1.3 Benzene 3.1.4 Methylene chloride 3.1.5 Perchloroethylene 3.1.6 MTBE o 3.2 Indoor air o 3.3 Regulation of indoor VOC emissions o 3.4 Formaldehyde 4 Health risks o 4.1 Reducing exposure o 4.2 Limit values for VOC emissions 5 Chemical fingerprinting 6 VOC sensors 7 See also 8 References 9 External links Definitions[edit] Diverse definitions of the term VOC[2] are in use. The definitions of VOCs used for control of precursors of photochemical smog used by the EPA, and states in the US with independent outdoor air pollution regulations include exemptions for VOCs that are determined to be non-reactive, or of low-reactivity in the smog formation process. EPA formerly defined these compounds as reactive organic gases (ROG) but changed the terminology to VOC.[citation needed] In the USA, different regulations vary between states - most prominent is the VOC regulation by SCAQMD and by the California Air Resources Board.[3] However, this specific use of the term VOCs can be misleading, especially when applied to indoor air quality because many chemicals that are not regulated as outdoor air pollution can still be important for indoor air pollution. Canada[edit] Health Canada classes VOCs as organic compounds that have boiling points roughly in the range of 50 to 250 °C (122 to 482 °F). The emphasis is placed on commonly encountered VOCs that would have an effect on air quality.[4] European Union[edit] A VOC is any organic compound having an initial boiling point less than or equal to 250 °C (482 °F) measured at a standard atmospheric pressure of 101.3 kPa[5] and can do damage to visual or audible senses.[citation needed] US[edit] VOCs (or specific subsets of the VOCs) are legally defined in the various laws and codes under which they are regulated. Other definitions may be found from government agencies investigating or advising about VOCs.[6] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates VOCs in the air, water, and land. The Safe Drinking Water Act implementation includes a list labeled "VOCs in connection with contaminants that are organic and volatile."[7] The EPA also publishes testing methods for chemical compounds, some of which refer to VOCs.[8] In addition to drinking water, VOCs are regulated in discharges to waters (sewage treatment and stormwater disposal), as hazardous waste,[9] but not in non industrial indoor air.[10] The United States Department of Labor and its Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulate VOC exposure in the workplace. Volatile organic compounds that are hazardous material would be regulated by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration while being transported. Biologically generated VOCs[edit] Not counting methane, biological sources emit an estimated 1150 teragrams of carbon per year in the form of VOCs.[11] The majority of VOCs are produced by plants, the main compound being isoprene. The remainder are produced by animals, microbes, and fungi, such as molds. The strong odor emitted by many plants consists of green leaf volatiles, a subset of VOCs. Emissions are affected by a variety of factors, such as temperature, which determines rates of volatilization and growth, and sunlight, which determines rates of biosynthesis. Emission occurs almost exclusively from the leaves, the stomata in particular. A major class of VOCs is terpenes, such as myrcene.[12] Providing a sense of scale, a forest 62,000 km2 in area (the U.S. state of Pennsylvania) is estimated to emit 3,400,000 kilograms of terpenes on a typical August day during the growing season.[13] VOCs should be a factor in choosing which trees to plant in urban areas.[14] Induction of genes producing volatile organic compounds, and subsequent increase in volatile terpenes has been achieved in maize using (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol and other plant hormones.[15] Anthropogenic sources[edit] Anthropogenic sources emit about 142 teragrams of carbon per year in the form of VOCs.[11] Specific components[edit] Paints and coatings[edit] A major source of man-made VOCs are coatings, especially paints and protective coatings. Solvents are required to spread a protective or decorative film. Approximately 12 billion litres of paints are produced annually. Typical solvents are aliphatic hydrocarbons, ethyl acetate, glycol ethers, and acetone. Motivated by cost, environmental concerns, and regulation, the paint and coating industries are increasingly shifting toward aqueous solvents.[16] Chlorofluorocarbons and chlorocarbons[edit] Chlorofluorocarbons, which are banned or highly regulated, were widely used cleaning products and refrigerants. Tetrachloroethene is used widely in dry cleaning and by industry. Industrial use of fossil fuels produces VOCs either directly as products (e.g., gasoline) or indirectly as byproducts (e.g., automobile exhaust).[citation needed] Benzene[edit] Main article: Benzene One VOC that is a known human carcinogen is benzene, which is a chemical found in environmental tobacco smoke, stored fuels, and exhaust from cars. Benzene also has natural sources such as volcanoes and forest fires. It is frequently used to make other chemicals in the production of plastics, resins, and synthetic fibers. Benzene evaporates into the air quickly and the vapor of benzene is heavier than air allowing the compound to sink into low-lying areas. Benzene has also been known to contaminate food and water and if digested can lead to vomiting, dizziness, sleepiness, rapid heartbeat, and at high levels, even death may occur.[citation needed] Methylene chloride[edit] Methylene chloride is another VOC that is highly dangerous to human health. It can be found in adhesive removers and aerosol spray paints and the chemical has been proven to cause cancer in animals. In the human body, methylene chloride is converted to carbon monoxide and a person will suffer the same symptoms as exposure to carbon monoxide. If a product that contains methylene chloride needs to be used the best way to protect human health is to use the product outdoors. If it must be used indoors, proper ventilation is essential to keeping exposure levels down.[citation needed] Perchloroethylene[edit] Perchloroethylene is a volatile organic compound that has been linked to causing cancer in animals. It is also suspected to cause many of the breathing related symptoms of exposure to VOCs.[citation needed] Perchloroethylene is used mostly in dry cleaning. While dry cleaners recapture perchloroethylene in the dry cleaning process to reuse it, some environmental release is unavoidable. Studies show that people breathe in low levels of this VOC in homes where drycleaned clothes are stored and while wearing dry-cleaned clothing.[citation needed] MTBE[edit] MTBE was banned in the US around 2004 in order to limit further contamination of drinking water aquifers primarily from leaking underground gasoline storage tanks where MTBE was used as an octane booster and oxygenated-additive.[citation needed] Indoor air[edit] Main article: Indoor air quality Since many people spend much of their time indoors, long-term exposure to VOCs in the indoor environment can contribute to sick building syndrome.[17] In offices, VOC results from new furnishings, wall coverings, and office equipment such as photocopy machines, which can offgas VOCs into the air.[18][19] Good ventilation and air-conditioning systems are helpful at reducing VOCs in the indoor environment.[18] Studies also show that relative leukemia and lymphoma can increase through prolonged exposure of VOCs in the indoor environment.[20] There are two standardized methods for measuring VOCs, one by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and another by Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Each method uses a single component solvent; butanol and hexane cannot be sampled, however, on the same sample matrix using the NIOSH or OSHA method.[21] The aromatic VOC compound benzene, emitted from exhaled cigarette smoke is labeled as carcinogenic, and is ten times higher in smokers than in nonsmokers.[18] The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has found concentrations of VOCs in indoor air to be 2 to 5 times greater than in outdoor air and sometimes far greater. During certain activities indoor levels of VOCs may reach 1,000 times that of the outside air.[22] Studies have shown that individual VOC emissions by themselves are not that high in an indoor environment, but the indoor total VOC (TVOC) concentrations can be up to five times higher than the VOC outdoor levels.[23] New buildings especially, contribute to the highest level of VOC off-gassing in an indoor environment because of the abundant new materials generating VOC particles at the same time in such a short time period.[17] In addition to new buildings, we also use many consumer products that emit VOC compounds, therefore the total concentration of VOC levels is much greater within the indoor environment.[17] VOC concentration in an indoor environment during winter is three to four times higher than the VOC concentrations during the summer.[24] High indoor VOC levels are attributed to the low rates of air exchange between the indoor and outdoor environment as a result of tight-shut windows and the increasing use of humidifiers.[25] Regulation of indoor VOC emissions[edit] In most countries, a separate definition of VOCs is used with regard to indoor air quality that comprises each organic chemical compound that can be measured as follows: Adsorption from air on Tenax TA, thermal desorption, gas chromatographic separation over a 100% nonpolar column (dimethylpolysiloxane). VOC (volatile organic compounds) are all compounds that appear in the gas chromatogram between and including n-hexane and n-hexadecane. Compounds appearing earlier are called VVOC (very volatile organic compounds) compounds appearing later are called SVOC (semi-volatile organic compounds). See also these standards: ISO 160006, ISO 13999-2, VDI 4300-6, German AgBB evaluating scheme, German DIBt approval scheme, GEV testing method for the EMICODE. Some overviews over VOC emissions rating schemes [26] have been collected and compared. France and Germany have enacted regulations to limit VOC emissions from commercial products, and industry has developed numerous voluntary ecolabels and rating systems, such as EMICODE,[27] M1,[28] Blue Angel[29] and Indoor Air Comfort[30] In the United States, several standards exist; California Standard CDPH Section 01350[31] is the most popular one. Over the last few decades, these regulations and standards changed the marketplace, leading to an increasing number of low-emitting products: The leading voluntary labels report that licenses to several hundreds of low-emitting products have been issued (see the respective webpages such as MAS Certified Green.- Certified Products[32]). Formaldehyde[edit] Many building materials such as paints, adhesives, wall boards, and ceiling tiles slowly emit formaldehyde, which irritates the mucous membranes and can make a person irritated and uncomfortable.[18] Formaldehyde emissions from wood are in the range of 0.02 – 0.04 ppm. Relative humidity within an indoor environment can also affect the emissions of formaldehyde. High relative humidity and high temperatures allow more vaporization of formaldehyde from wood-materials.[33] Health risks[edit] Respiratory, allergic, or immune effects in infants or children are associated with man-made VOCs and other indoor or outdoor air pollutants.[34] Some VOCs, such as styrene and limonene, can react with nitrogen oxides or with ozone to produce new oxidation products and secondary aerosols, which can cause sensory irritation symptoms.[18][35] Unspecified VOCs are important in the creation of smog.[36] Health effects include eye, nose, and throat irritation; headaches, loss of coordination, nausea; damage to liver, kidney, and central nervous system. Some organics can cause cancer in animals; some are suspected or known to cause cancer in humans. Key signs or symptoms associated with exposure to VOCs include conjunctival irritation, nose and throat discomfort, headache, allergic skin reaction, dyspnea, declines in serum cholinesterase levels, nausea, vomiting, nose bleeding, fatigue, dizziness.[citation needed] The ability of organic chemicals to cause health effects varies greatly from those that are highly toxic, to those with no known health effects. As with other pollutants, the extent and nature of the health effect will depend on many factors including level of exposure and length of time exposed. Eye and respiratory tract irritation, headaches, dizziness, visual disorders, and memory impairment are among the immediate symptoms that some people have experienced soon after exposure to some organics. At present, not much is known about what health effects occur from the levels of organics usually found in homes. Many organic compounds are known to cause cancer in animals; some are suspected of causing, or are known to cause, cancer in humans.[37] Reducing exposure[edit] To reduce exposure to these toxins, one should buy products that contain Low-VOCs or No VOCs. Only the quantity which will soon be needed should be purchased, eliminating stockpiling of these chemicals. Use products with VOCs in well ventilated areas. When designing homes and buildings, design teams can implement the best possible ventilation plans, call for the best mechanical systems available, and design assemblies to reduce the amount of infiltration into the building. These methods will help improve indoor air quality, but by themselves they cannot keep a building from becoming an unhealthy place to breathe.[citation needed] Limit values for VOC emissions[edit] Limit values for VOC emissions into indoor air are published by e.g. AgBB, AFSSET, California Department of Public Health, and others. These regulations have prompted several companies to adapt with VOC level reductions in products that have VOCs in their formula, such Benjamin Moore & Co. in the paint industry and Weld-On in the adhesive industry.[citation needed] Chemical fingerprinting[edit] The exhaled human breath contains a few hundred volatile organic compounds and is used in breath analysis to serve as a VOC biomarker to test for diseases such as lung cancer.[38] One study has shown that "volatile organic compounds ... are mainly blood borne and therefore enable monitoring of different processes in the body."[39] And it appears that VOC compounds in the body "may be either produced by metabolic processes or inhaled/absorbed from exogenous sources" such as environmental tobacco smoke.[38][40] Research is still in the process to determine whether VOCs in the body are contributed by cellular processes or by the cancerous tumors in the lung or other organs. VOC sensors[edit] Main article: VOC sensors VOCs in the environment or certain atmospheres can be detected based on different principles and interactions between the organic compounds and the sensor components. There are electronic devices that can detect ppm concentrations despite the non-selectivity. Others can predict with reasonable accuracy the molecular structure of the volatile organic compounds in the environment or enclosed atmospheres[41] and could be used as accurate monitors of the Chemical Fingerprint and further as health monitoring devices. Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) techniques are used to collect VOCs at low concentrations for analysis.[42] See also[edit] Aroma compound Criteria air contaminants Dutch standards Fugitive emissions NMVOC (non-methane volatile organic compounds) NoVOC (classification) Organic compound Photochemical smog Volatility (chemistry) NTA Inc VOC Testing Laboratory Volatile Organic Compounds Protocol Ozone References[edit] 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. Jump up ^ "Plants: A Different Perspective". Content.yudu.com. Retrieved 2012-07-03. Jump up ^ "What does VOC mean?". Eurofins.com. Retrieved 2012-07-03. Jump up ^ California ARB Jump up ^ Health Canada Jump up ^ Directive 2004/42/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on the limitation of emissions of volatile organic compounds due to the use of organic solvents in certain paints and varnishes and vehicle refinishing products EUR-Lex, European Union Publications Office. Retrieved on 2010-09-28. Jump up ^ USGS definition Jump up ^ 40CFR141 Jump up ^ "Clean Water Act Analytical Methods | CWA Methods | US EPA". Epa.gov. Retrieved 2012-0703. Jump up ^ CERCLA and RCRA Jump up ^ "Volatile Organic Compounds | Indoor Air | US Environmental Protection Agency". Epa.gov. 2010-11-17. Retrieved 2012-07-03. ^ Jump up to: a b Goldstein, Allen H.; Galbally, Ian E. (2007). "Known and Unexplored Organic Constituents in the Earth's Atmosphere". Environmental Science & Technology 41 (5): 1514–21. doi:10.1021/es072476p. PMID 17396635. Jump up ^ Niinemets, Ülo; Loreto, Francesco; Reichstein, Markus (2004). "Physiological and physicochemical controls on foliar volatile organic compound emissions". Trends in Plant Science 9 (4): 180–6. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2004.02.006. PMID 15063868. Jump up ^ Behr, Arno; Johnen, Leif (2009). "Myrcene as a Natural Base Chemical in Sustainable Chemistry: A Critical Review". ChemSusChem 2 (12): 1072–95. doi:10.1002/cssc.200900186. PMID 20013989. Jump up ^ Xie, Jenny. "Not All Tree Planting Programs Are Great for the Environment". City Lab. Atlantic Media. Retrieved 20 June 2014. Jump up ^ Farag, Mohamed A.; Fokar, Mohamed; Abd, Haggag; Zhang, Huiming; Allen, Randy D.; Paré, Paul W. (2004). "(Z)-3-Hexenol induces defense genes and downstream metabolites in maize". Planta 220 (6): 900–9. doi:10.1007/s00425-004-1404-5. PMID 15599762. Jump up ^ Stoye, D.; Funke, W.; Hoppe, L. et al. (2006). "Paints and Coatings". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_359.pub2. ISBN 3527306730.edit ^ Jump up to: a b c Wang, Shaobin; Ang, H.M.; Tade, Moses O. (2007). "Volatile organic compounds in indoor environment and photocatalytic oxidation: State of the art". Environment International 33 (5): 694–705. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2007.02.011. PMID 17376530. 18. ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Dales, R.; Liu, L.; Wheeler, A. J.; Gilbert, N. L. (2008). "Quality of indoor residential air and health". Canadian Medical Association Journal 179 (2): 147–52. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070359. PMC 2443227. PMID 18625986. 19. Jump up ^ Yu, Chuck; Crump, Derrick (1998). "A review of the emission of VOCs from polymeric materials used in buildings". Building and Environment 33 (6): 357–74. doi:10.1016/S0360-1323(97)00055-3. 20. Jump up ^ Irigaray, P.; Newby, J.A.; Clapp, R.; Hardell, L.; Howard, V.; Montagnier, L.; Epstein, S.; Belpomme, D. (2007). "Lifestyle-related factors and environmental agents causing cancer: An overview". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 61 (10): 640–58. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2007.10.006. PMID 18055160. 21. Jump up ^ Who Says Alcohol and Benzene Don't Mix?[dead link] 22. Jump up ^ An Introduction to Indoor Air Quality 23. Jump up ^ Jones, A.P. (1999). "Indoor air quality and health". Atmospheric Environment 33 (28): 4535–64. doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00272-1. 24. Jump up ^ Barro, R.; Regueiro, J.; Llompart, M. A.; Garcia-Jares, C. (2009). "Analysis of industrial contaminants in indoor air: Part 1. Volatile organic compounds, carbonyl compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls". Journal of Chromatography A 1216 (3): 540–566. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2008.10.117. PMID 19019381.edit 25. Jump up ^ Schlink, U; Rehwagen, M; Damm, M; Richter, M; Borte, M; Herbarth, O (2004). "Seasonal cycle of indoor-VOCs: Comparison of apartments and cities". Atmospheric Environment 38 (8): 1181–90. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2003.11.003. 26. Jump up ^ "Ecolabels, Quality Labels, and VOC emissions". Eurofins.com. Retrieved 2012-07-03. 27. Jump up ^ EMICODE 28. Jump up ^ M1 Finnish label 29. Jump up ^ Blue Angel German ecolabel 30. Jump up ^ Indoor Air Comfort 31. Jump up ^ CDPH Section 01350 32. Jump up ^ IAQ Certified Products 33. Jump up ^ Wolkoff, Peder; Kjaergaard, Søren K. (2007). "The dichotomy of relative humidity on indoor air quality". Environment International 33 (6): 850–7. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2007.04.004. PMID 17499853. 34. Jump up ^ Mendell, M. J. (2007). "Indoor residential chemical emissions as risk factors for respiratory and allergic effects in children: A review". Indoor Air 17 (4): 259–77. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00478.x. PMID 17661923. 35. Jump up ^ Wolkoff, P.; Wilkins, C. K.; Clausen, P. A.; Nielsen, G. D. (2006). "Organic compounds in office environments - sensory irritation, odor, measurements and the role of reactive chemistry". Indoor Air 16 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2005.00393.x. PMID 16420493. 36. Jump up ^ "What is Smog?", Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, CCME.ca 37. Jump up ^ EPA -- An Introduction to Indoor Air Quality Pollutants and Sources of Indoor Air Pollution Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) 38. ^ Jump up to: a b Buszewski, B. A.; Kesy, M.; Ligor, T.; Amann, A. (2007). "Human exhaled air analytics: Biomarkers of diseases". Biomedical Chromatography 21 (6): 553–566. doi:10.1002/bmc.835. PMID 17431933.edit 39. Jump up ^ Miekisch, W.; Schubert, J. K.; Noeldge-Schomburg, G. F. E. (2004). "Diagnostic potential of breath analysis—focus on volatile organic compounds". Clinica Chimica Acta 347: 25. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2004.04.023.edit 40. Jump up ^ Mazzone, P. J. (2008). "Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds in the Exhaled Breath for the Diagnosis of Lung Cancer". Journal of Thoracic Oncology 3 (7): 774–780. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817c7439. PMID 18594325. 41. Jump up ^ MartíNez-Hurtado, J. L.; Davidson, C. A. B.; Blyth, J.; Lowe, C. R. (2010). "Holographic Detection of Hydrocarbon Gases and Other Volatile Organic Compounds". Langmuir 26 (19): 15694–9. doi:10.1021/la102693m. PMID 20836549. 42. Jump up ^ Lattuati-Derieux, Agnès; Bonnassies-Termes, Sylvette; Lavédrine, Bertrand (2004). "Identification of volatile organic compounds emitted by a naturally aged book using solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography/mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography A 1026 (1–2): 9– 18. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2003.11.069. PMID 14870711. External links[edit] Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) web site of the Chemicals Control Branch of Environment Canada[dead link] An Introduction to Indoor Air Quality, US EPA website VOC in paints, finishes and adhesives VOC emissions testing EPA NE: Ground-level Ozone (Smog) Information emission from crude oil tankers VOC emissions and calculations VOCs, ozone and air pollution information from the American Lung Association of New England VOC Tests Post doc in Volatile organic compound in Food VOC emissions from printing processes, European legislation and biological treatment Examples of product labels with low VOC emission criteria Information about VOCs in Drinking Water Formaldehyde and VOCs in Indoor Air Quality Determinations by GC/MS