"I Just Went To Pieces": Vietnam and the Rise of Post Traumatic

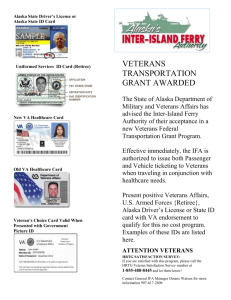

advertisement

1 Michael Gilmore “I Just Went to Pieces”: Vietnam and the Rise of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder What many soldiers found in Vietnam was not glory and heroics but the terror of combat and the brutality of war. As one soldier recounts, “Alpha and Bravo companies were wiped out and we were sent in to pick up the bodies. After three days in the hot sun the bodies stunk. I picked up one and the arms came off in my hands. All the time we were under fire. I couldn’t help myself. I just went to pieces.”1 Disturbing as they were, such experiences were played out time and time again throughout the Vietnam War. Many young men left for combat believing they would, as one soldier put it, “turn Vietnam into a grease spot.”2 Rather than turning the country into a “grease spot,” combat soldiers witnessed and committed atrocities they could have never imagined. They returned home, not to parades and fanfare as the previous generation had during the Second World War, but to a society that saw their war as immoral and undeserving of thanks. However, through the pain and suffering soldiers experienced upon returning to an unwelcoming society, mental health evolved tremendously. Prior to the Vietnam War, little attention was given to the psychological effects of combat and mainstream mental health was still some time away from coining the term “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.” It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that the Vietnam War brought combat-induced mental trauma to the forefront of society’s awareness. Much of the scholarly work regarding the introduction of mental health treatment for veterans of the Vietnam War seems to focus primarily on the causes of mental health 1 2 Nordheimer Jones, "Postwar Shock Besets Veterans of Vietnam," New York Times, Aug 28, 1972. Jones, “Postwar Shock,”. 2 issues themselves. For example, Charles Figgly, who in 1978 published one of the most influential works regarding PTSD and Vietnam, Stress Disorders Among Vietnam Veterans, focuses overwhelmingly on why Vietnam created so many cases of PTSD.3 Prior to the Vietnam War, mental health professionals had not conducted sufficient research regarding the development of this disease. Because of this, it appears as though this period brought about a large influx of studies regarding the development of such mental trauma. The primary goal of this work, in contrast, will be to determine why these cases suddenly received so much attention in the mental health community and in society at large, throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Conducting such research will provide critical insight into the modern understanding of the nature of war and the formation of mental illness. The experiences of veterans after returning from Vietnam have arguably shaped the manner in which traumatic experiences are handled in the psychological community today and are therefore extremely significant. Although scholars have done little to discuss the reasons for the rise of PTSD in society, this work will examine the reason for this rise. The factors that contributed to the acknowledgement and treatment of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) during and immediately after the Vietnam War were three-fold. First, the sociocultural context of America during the 1960s and 1970s was conducive to the development and exacerbation of PTSD symptoms in returning combat veterans. Second, although the Veterans Administration (VA) hospital system had become financially capable of treating veterans, its mental health facilities were lacking in quality. The final factor was the result of veteran activism. Through the lobbying of frustrated Vietnam veterans, important reforms were 3 Charles Figgly, Stress Disorders Among Vietnam Veterans (New York: Brunner/Mazel, Inc., 1978), NP. 3 made to the VA system and the field of mental health to provide for the treatment of mental illness. *** Although PTSD became a “mainstream” mental health concern during the Vietnam War and in the decades that followed, the disease has affected veterans throughout the history of warfare. One of the earliest examples of PTSD comes from the writings of Greek historian Herodotus after the battle of Marathon in 490 BC.4 Steve Bentley, Chairman of the Vietnam Veterans of America PTSD and Substance Abuse Committee, notes that Herodotus wrote an account of an Athenian soldier who, despite being physically unharmed, became blind after witnessing the gruesome death of a comrade.5 This exemplifies that the issue of combat trauma was not new during the Vietnam War but had been a prevalent issue for veterans throughout history. Many years after Herodotus, in the early 20th century, warfare continued to create trauma as well as some of the most important advances in the field of mental health. Author Edgar Jones argues that the nature of combat in World War One, with its prolonged periods of service in the trenches and vast improvements in tools of killing, brought many medical professionals to the combat front. With this influx of physicians, Jones continues, came an interest in categorizing and detailing the physical and psychological symptoms exhibited by combat soldiers. This brought the term “shell shock” into mainstream culture. 6 Shell shock was the term used for the physical symptoms brought about by intense combat. Physicians originally thought of these symptoms as 4 Steve Bentley. The VVA Veteran--A Short History of PTSD (Jan. 1991): NP. Bentley, The VVA. 6 Edgar Jones. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychology from 1900 to the Gulf War (New York: Psychology Press, 2005), 2-10. 5 4 resulting from the injury of being in close proximity to an exploding artillery shell. They believed the condition was purely physical due to the fact that the symptoms, including “amnesia, poor concentration, headache, tinnitus, hypersensitivity to noise, and tremor” resembled the symptoms experienced by the victims of head trauma.7 This continued to be a widespread belief in military medicine throughout World War Two and into the Vietnam War. Soldiers returning home from Vietnam carried tremendous emotional baggage that contributed to the development of mental illness. It quickly became clear that they were suffering from emotional scars that had little to do with their physical wounds. Society began realizing that the issues facing veterans of Vietnam were unique and began abandoning the term “shell shock.” According to a New York Times article from 1972, “Perhaps the most commonly reported symptoms of what has been called the ‘postVietnam syndrome’ are sense of shame and guilt for having participated in a war that the veteran now questions.”8 Because many soldiers felt that America’s involvement in Vietnam was unjust, many unsuccessfully grappled with the moral implications of committing and witnessing atrocities in what they viewed as an unethical war. The sociocultural context of the 1960s and 1970s created conditions that worsened the mental health issues experienced by combat veterans, eventually bringing PTSD to the public’s attention. When many soldiers returned from the war, they often assumed they would be treated similarly to how veterans had been after the Second World War, with celebration and honor. However, this was not the case. There were few parades or special WA Turner, “Cases of Nervous and Mental Shock Observed in the Base Hospitals in France,” J R Army Med Corps 24 (1914): 343–352. 8 Boyce Rensberger, “Delayed Trauma in Veterans Cited: Psychiatrists Find Vietnam Produces Guilt and Shame,” New York Times, May 3, 1972. 7 5 treatment and business owners were frequently less than eager to hire Vietnam veterans. Such ambivalence in society created negative feedback, which worsened the mental issues plaguing combat veterans. In order to cope with emotional stress, soldiers became increasingly desperate, turning to detrimental methods of dealing with emotion issues. Family issues, drug use, and violence became particularly high in veteran populations, leading the general public to acknowledge that the mental health issues facing veterans were extraordinary. For many returning veterans, the support from family, friends, and society at large felt inadequate, leading to increased mental anguish. For example, divorce rates among combat veterans proved to be abnormally high for the time. According statistics published in the New York Times in 1975, “Of those who were married before they went to Vietnam, 38 per cent were separated or getting divorced six months after their return.”9 High divorce rates demonstrate the family issues experienced by veterans. The dissolution of family bonds would be detrimental because it would deprive veterans of one of the most crucial forms of social support. In addition to high rates of divorce, veterans often found little aid from pre-service relationships. One individual, referred to only as “Norman” to protect his anonymity, is quoted in a New York Times article as saying, “Why are they afraid of us? Why do they ask us questions about how many we killed? I killed a few, but I don’t want to talk about it.”10 This quote represents a difficulty many veterans had in adjustment. Questions such as these would likely drudge up topics and memories that veterans were ashamed of and did not wish to discuss. Additionally, such scenarios may encourage veterans to become 9 Tom Wicker, “The Vietnam Disease,” The New York Times, May 27, 1975. Nordheimer, "Postwar Shock". 10 6 increasingly withdrawn from society, fearing that pre-war acquaintances would be unable to understand or sympathize with their experiences. Such scenarios would further deprive veterans of their social supports by stripping them of friendship ties. Another such example comes from a “Dear Abby” letter published in the Los Angeles Times by the mother of a soldier stationed in Vietnam. The mother claims she berated her son because he asked that his wife meet him at the airport rather than his parents.11 Like Norman’s case, the overbearing mother demonstrates that even direct family members could not relate to the situation and needs of veterans, regardless of pre-service connections. If a veteran felt unable to be supported by family and friends, it is likely that they would resort to more damaging methods of coping with their mental stress. High unemployment and unsuccessful job searches also lead to further complications and isolation among veterans. According to author Seymour Leventman, “at one point in 1971 there were more unemployed veterans, 330,000, than there were troops in Vietnam.”12 Without the ability to support themselves financially, many veterans must have felt increasing levels of social isolation and abandonment. Arthur Egendorf Jr., a veteran of the war and a student of psychology, expressed these sentiments in an editorial he wrote for the New York Times in September of 1972, claiming, “Growing numbers of us have concluded that it is not we who are in need of treatment, but rather the society that sent us to war.”13 The deprivation of employment would cost veterans their ability to return some sense of normalcy to their lives. Unlike the veterans of World War II, who often found employment quickly because of the post-war economic boom, veterans of 11 Abigail Van Buren, “Family War Goes on for Returning Vietnam Veterans,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1967. 12 Seymour Leventman, “Official Neglect of Vietnam Veterans,” Journal of Social Issues 31, no. 4 (1975): 175. 13 Arthur Egendorf Jr, “The Ones Who Came Home,” The New York Times, September 15, 1972. 7 Vietnam became subject to long periods of unemployment. These periods would give them more free time to dwell on traumatic events experienced in Vietnam. Along with the dissolution of family and friendship bonds, a lack of employment likely led to further isolation within society. The negative experiences many veterans had with family, friends, and employment directly contributed to a rise in PTSD. Although the field of mental health was not developed enough by the mid-1960s to understand the connection between social interaction and PTSD, modern science has since established a direct correlation. A recent study conducted by a team primarily compromised of doctors from the Harvard Medical School found that individuals who reported “less perceived negative dyadic interaction would report less severe initial negative post-trauma cognitions”.14 In other words, the best way to mitigate negative mental health issues in returning veterans is to provide them with positive reinforcement, as those who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder seem unable to handle negative social interaction in a proactive manner. However, socioeconomic conditions after Vietnam often removed many of these positive supports including family, friends, and employment. Negative social interaction became the typical experience for many veterans, and resulted in the worsening of mental health issues. In addition to the importance of positive social interaction, support systems and society itself are considered crucial factors in preventing the exacerbation of PTSD. One study, conducted by the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi in conjunction with the University of Mississippi Medical Center, proves this correlation within communities of Vietnam veterans. By comparing Vietnam veterans diagnosed with Donald J. Robinaugh, "Understanding the relationship of perceived social support to post-trauma cognitions and posttraumatic stress disorder," Journal of Anxiety Disorders 25 (2011): 1072-1078. 14 8 PTSD, Vietnam veterans diagnosed to be “well-adjusted”, and Vietnam veterans who did not experience combat, the study determined that there was a discrepancy in the way each group viewed the support systems upon returning from Vietnam, leading to varying degrees of PTSD symptoms correlating to service conditions.15 According to the study, “For the PTSD veterans, qualitative and quantitative measures of social support systematically declined over time…whereas for the comparison groups, social support was either stable or improved over time.”16 In other words, those veterans who were “well-adjusted” or who did not experience combat, felt as though the social support provided was adequate. However, considering that those diagnosed with PTSD saw social supports as inadequate suggests that society misunderstood the issues affecting combat veterans and did not have the knowledge or capability of treating the disease. The issue of drug abuse among veterans, though often dramatized by the media catered to the fears of the public, caused society to increase its understanding of mental health issues. The media often portrayed veterans as hopeless junkies addicted to heroin. One article from the New York Times in 1974 stated that the war “has left thousands of veterans embroiled with the whole range of illicit drugs that saturated American forces in Vietnam.”17 Another article, from the Los Angeles Times, asserted that the problem of drug addiction among veterans was so extensive that, “the drug problem alone was reason enough to speed troop pullouts.”18 Inflammatory and sensational journalism captured the 15 Terence Keane, Scott W. Own, and Gary A. Chavoya, "Social Support in Vietnam Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Comparative Analysis," Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 53, no. 1 (1985): 95-102. 16 Keane, “Social Support”, 95-102. 17 M.A. Farber, “Veterans Still Fight Vietnam Drug Habits,” New York Times, June 2, 1974. 18 “Soaring Drug Use Called Reason to Speed GI Pullout,” Los Angeles Times, May 28, 1971. 9 attention of the public, leading many to fear that the streets of America would soon overflow with junkie veterans searching for their next fix. Though exaggerated to a significant degree, drug use in veterans was a pervasive issue that symbolized one of the many readjustment problems facing veterans suffering from PTSD. The result of a 1972 Harris poll found that 32% of the veterans questioned had used drugs while in service and 50% of that figure stated that they had used drugs since returning home.19 All veterans did not fall into the category of “drug addict” and it is likely that the majority of combat soldiers never experimented with drugs. However, in a nation that demonized drug use and feared a drug epidemic, much of the population would perceive veteran drug addicts as threatening figures and thus push them to the margins of society. Although it resulted in the unfair stereotype of soldiers as addicts, drug use clearly played a role attracting the attention of the American public. Like drug use, high rates of violent crime among veterans contributed to the acknowledgement by society that many of those who served in Vietnam were deeply disturbed. In 1978, author Charles Figgly referred to the term “Post-Vietnam Syndrome” to describe the strange and occasionally psychotic behavior of returning veterans. PostVietnam Syndrome, or PVS, was an early explanation for why combat veterans of Vietnam faced such significant issues when readjusting to society. Although originally used in the field of psychology to primarily explain drug use and feelings of isolation, PVS gained notoriety in 1971 after police shot Sergeant Dwight Johnson, a recipient of the Medal of Honor, as he attempted to rob a local grocery store at gunpoint.20 Sergeant Johnson’s case 19 20 “Poll of Vietnam Veterans Finds Doubt Over Readjustment Aid,” New York Times, Jan 6, 1972. Figgly, Stress Disorders, 46. 10 publicly demonstrated the manner in which PTSD could affect an individual in a way that would create tragic results. Violent crimes committed by returning veterans were reported on regularly during the period of the late 1960s, into the 1970s and 1980s. These crimes, such as Sergeant Johnson’s shooting, garnered the public’s attention. In the 1973 case of Kemp v. State, a returning veteran, Kemp, “dreamed that an armed Vietcong soldier invaded the bedroom where he and his wife slept”. In this post-war hallucination, Kemp killed the imaginary Vietcong soldier only to later discover that he had, in fact, shot and killed his wife.21 Such a disturbing case demonstrated that veterans could impact not only their own lives, but also the lives of their loved ones in violent ways. The sensationalist media of the 1960s and 1970s was very much interested in stories of violence and tragedy and eagerly reported on violent crimes perpetrated by veterans, pushing the issue into public view. Upon returning to America, veterans did not receive positive support, which often lead to erratic and tragic behavior. Spouses seemed unable to provide emotional support, leading to high divorce rates while friends often asked insensitive questions such as, “how many did you kill?” Without the factors needed to mitigate PTSD, many veterans began to suffer from symptoms that led to violent crimes, such as the case of Sergeant Johnson. However, through these tragic incidents, the public and the field of mental health began to understand that the cognitive response of veterans was unusual, leading to an acknowledgment that veterans suffered from severe mental trauma. Although many veterans were likely as disturbed as Johnson and Kemp, they nonetheless had to reintegrate themselves into a society with little regard for their 21 Barbara Minette Jones, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the United States Legal Culture: An Historical Perspective from World War I Through the Vietnam Conflict (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Bell and Howell, 1995), 135. 11 emotional well-being. With little or no transition period, society expected veterans to find employment, raise a family, and move on with their lives in the way veterans of World War II had. However, as author Donald Catherall points out, many Vietnam veterans were not mentally capable of reintegrating themselves into society in such a way. Catherall argues, “many veterans appear stuck at the point immediately following the trauma, still reeling from the experience”.22 He believes that because society did not provide adequate resources to aid veterans in readjustment, many withdrew themselves emotionally. In his view, much of American society, believing the war was unjust, created an environment in which returning veterans felt guilt and immorality due to their service.23 When considering that positive reinforcement is crucial for the readjustment of combat veterans, a lack of support would be devastating. As Catherall also notes in his work, readjustment problems such as high crime rates represented the extraordinary degree to which PTSD had developed in many veterans.24 However, the behavior of veterans upon returning home contributed to the solution by forcing the public to acknowledge the mental instability of many who served in the war. The prevalence of PTSD that rose out of the Vietnam-era could not have been adequately treated without extensive medical resources. The Veterans Administration (VA), designed to provide medical benefits to American veterans, was in a financially sound position by the late 1960s. Although the US government established this system of veteran care decades prior, it was not until veterans began returning from Vietnam that the VA made the changes necessary to adequately care for America’s combat veterans. Donald Catherall. “The Support System and Amelioration of PTSD in Vietnam Veterans,” Psychotherapy 23, no. 1 (1986): 475. 23 Catherall, “The Support System,” 475. 24 Catherall, “The Support System,” 475. 22 12 The situation of veteran care evolved dramatically in the decades prior to the Vietnam War. Up to the First World War, the role of the VA was primarily to provide “domiciliary care” or housing to veterans struggling with wounds inflicted in combat.25 World War II caused exponential expansion of the system to accommodate the large number of returning veterans.26 The growth that occurred during and after World War II provided the basis for care that veterans of the Vietnam War would receive. However, as the Vietnam War progressed, it became clear to the VA that Vietnam provided challenges that had not yet been witnessed throughout the course of previous American wars. The Vietnam War put incredible logistical strains on the Veterans Administration, demonstrating its inadequacies. Author Stephen P. Backhus notes that, “admissions to VA hospitals more than doubled from 1963 through 1980, from 585,000 to 1,183,000.”27 By 1970, it became clear that the VA did not possess the resources to adequately treat the large influx of veterans. For this reason, Congress approved a $9 billion appropriation to fund medical care, readjustment benefits, and research.28 Even after the increase in funds, the VA continued to struggle to treat the enormous number of veterans. According to a 1972 Harris Poll, “only half of the veterans polled said they thought the Veterans Administration was advising them sufficiently on the benefits available to them.”29 This suggests that despite massive overhauls of the healthcare system and funding, veterans still did not feel their treatment was adequate. 25 United States General Accounting Office, Va Hospitals: Issues and Challenges for the Future, 1998. United States General Accounting Office, Va Hospitals. 27 United States General Accounting Office, Va Hospitals 28 “Senate Approves a $9-Billion Appropriation Measure for the Veterans Administration,” New York Times, July 10, 1970. 29 “Poll of Vietnam Veterans Finds Doubt Over Readjustment Aid,” New York Times, Jan 6, 1972. 26 13 The evolution of the VA, through increased admissions and funds likely led to an increased awareness of the needs of veterans. By the early 1970s, it appeared that America had begun to understand that the issues facing the veterans of Vietnam were unique. Additionally by this point, the VA had grown to the point that it possessed the financial resources to treat veterans and their unique problems. However, as the previously mentioned Harris Poll demonstrates, veterans still did not feel their treatment was adequate. This may be due in part to the fact that the field of mental health had not yet developed to the degree that it could adequately treat PTSD. It would take another, crucial factor to advance the field of mental health and cause the implementation of new psychological and psychiatric methods. Despite the massive increase in the resources at the VA’s disposal, as the Vietnam War continued to become increasingly intense, it continued to lack any truly effective method to treat the mental health issues plaguing veterans. Although it became clear that the field of mental health lagged as veterans continued to experience high rates of violent crimes, it was not apparent to the VA what changes should be made. Author Barbara Minette Jones argues that the solution did not come from the top-down, through expensive psychological studies or flashy political debates, but from the veterans themselves. Through political activism, Jones argues, veterans drew attention to their mental health needs, thus securing for themselves the treatment necessary to begin healing from their wounds.30 Prior to Vietnam and throughout the war, treatments for combat stress were inadequate, causing frustration among veterans. Beginning in the 1950s, tranquilizers 30 Jones, Post-Traumatic Stress, 91-92. 14 became the preferred method of sedating and calming patients who suffered from mental disorders that caused anxiety and mood changes.31 The irony, of course, is that veterans of Vietnam, who were at such a high risk of drug addiction, could be prescribed tranquilizers as treatment for combat stress. Additionally, with the inadequate treatment they received from chaplains and military psychologists they referred to as “shrinks”, veterans became increasingly disillusioned.32 One soldier expressed his frustration with chaplains when he stated, “Whatever we were doing – murder, atrocities – God was always on our side.”33 Once again, soldiers found irony in receiving mental health care from religious figures while they were forced to commit atrocities. Because many soldiers felt disillusioned by the war, many developed an extreme distrust for the American government. As a result, many veterans found themselves unwilling to seek treatment at VA facilities. Despite the resources, many viewed VA hospitals, as one New York Times article puts it, “a threatening extension of the ‘green machine’, the armed forces.”34 Despite the resources that had grown in the VA hospital system, many veterans were not willing to subject themselves to what they feared would be further exploitation and harm at the hands of the American government. The VA was also unwilling to provide treatment for many mental health issues facing veterans. Because the symptoms of PTSD often appear more than two years after service is over, VA facilities did not consider it a “service-connected problem” and would John W. Robinson, “A Chance for the Mentally Ill,” The Science News-Letter, 71, no. 17 (1957): 266. Figgly, Stress Disorders, 219. 33 Figgly, Stress Disorders, 219. 34 Farder, “Veterans Still Fight Vietnam Drug Habits.” 31 32 15 often deny veterans treatment.35 This led to further disillusion with the VA system in general, leading veterans to reject the idea of seeking treatment there. Because veterans had a distrust of the government and felt the services offered to them were inadequate, they took it upon themselves to secure treatment. One of the most effective forms of treating PTSD available to returning veterans came about with the formation of “rap groups”. Rap groups were small meetings, put together by veterans and mental health professionals. Unlike the treatment received at the VA, rap groups were much more casual, fostering an environment where veterans could meet together and discuss their issues under the supervision of a mental health professional.36 As previously mentioned, many veterans were not willing to seek treatment at VA hospitals and so rap groups served a crucial purpose in serving veterans. According to Vietnam veteran Arthur Egendorf, “other forms of help (family advice, Veterans Administration services, private psychotherapy) were either inadequate or totally unacceptable for ideological or emotional reasons.”37 The small, casual environment of rap groups appealed to veterans who had become disillusioned with “the system” and gave them an outlet for their stress. Rap groups were a useful resource for veterans for two primary reasons. First, they provided veterans with an outlet for their frustrations. The isolation felt by soldiers after their return, left many feeling that, as Egendorf puts it, “only a vet can understand.”38 Through this, rap groups became one of the most effective forms of treatment available to returning veterans because it allowed them to surround themselves with individuals who Marlene Cimons, “Rap Sessions as Therapy,” Los Angeles Times, July 30, 1979. Cimons, “Rap Sessions.” 37 Arthur Egendorf, "Vietnam Veteran Rap Groups and Themes of Postwar Life," Journal of Social Issues 31, no. 4 (1975): 112. 38 Egendorf, “Vietnam Veteran Rap Groups,” 112. 35 36 16 could relate to their unique problems. Secondly, their methods of discussion and understanding seemed years ahead of much of the psychotherapy treatments available at the time, considering that treatment such as tranquilizers did not always come off as sympathetic to the victim. Because of these two factors, rap groups became tremendously popular among veterans, giving them the crucial treatment they needed. Aside from being an effective form of psychological treatment, rap groups also became an important component of veterans’ lives upon their return. The establishment of rap groups was outside the control of the government; neither the VA nor any other government organization played a role in their establishment.39 This became important in establishing a sense of self-determination in the lives of those who felt they had little control over their own situation. Also, the creation of these groups laid the seeds for the construction of other important veteran groups as well, such as the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) in 1967 and the Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA) in 1978.40 However, the quiet, closed-meetings of the rap groups would not garner the attention needed to secure benefits necessary to treat rampant PTSD; such goals would require more extensive endeavors. For this reason, it became necessary for veterans to become involved in political activism, taking their cause to the streets and demanding benefits. Organizations such as the VVA and VVAW were crucial in drawing attention to the needs of veterans. Through organizations such as these, veterans protested the government and championed for rights. 39 40 Figgly, Stress Disorders, 211-218. Egendorf, “Vietnam Veteran Rap Groups,” 112. 17 One of the most significant cases of a veteran organization securing benefits for Vietnam veterans occurred in 1977. Many veterans began bringing claims to the VA that the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam had resulted in many of the physical ailments veterans suffered after the war. Although the VA and the United States government denied the claims, the VVA continued to push for compensation. In 1977, the organization brought a lawsuit against the VA, the Department of Defense, and the Dow Chemical Company (the manufacturers Agent Orange).41 Although the victory did little to bring immediate attention to the issue of PTSD, it created legitimacy for veteran organizations such as the VVA, which created an avenue through which veterans could pursue just benefits. As veteran organizations continued to gain notoriety, they also increased in numbers. With its budding reputation, membership exploded in the VVA by 1979, growing from a handful of members to a significant portion of the veteran population in a matter of years.42 Obviously, new members brought in not only larger numbers but larger funds as well. In part because of the improved financial situation of the organization and because of new leadership in the VA, the Vet Center Program was initiated throughout the Veterans Administration.43 The Vet Center Program was one of the first signs that the government was beginning to truly become responsive to the need of Vietnam veterans. As membership and power of organizations such as the VVA grew, as did the pressure they were able to put onto government figures. With the public’s attention cast on their problems, veterans involved in the VVA claimed that many in their organization would not go into VA facilities 41 Jones, Post-Traumatic Stress, 95. Robert Arnoldt, After the War: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the Vietnam Veteran in American Society (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Proquest Information and Learning Company, 2003), 120. 43 Arnoldt, After the War, 120. 42 18 because they were fearful of the bureaucracy within the system.44 In 1979, President Jimmy Carter, in part due to the insistence of veteran groups, established the Vietnam Veterans’ Outreach Program, which resulted in the creation of “vet centers.”45 The purpose of vet centers was to provide readjustment resources to veterans of Vietnam in small facilities, well out of the way of massive VA hospitals.46 Their construction signaled a turning point in the Veterans Administration’s attitude toward the treatment of Vietnam veterans. Prior to the influence of the VVA, the VA was dismissive of psychological issues facing veterans. Favoring methods used in previous wars, there were few resources within the VA system that veterans suffering from PTSD could utilize.47 However, the influence of the VVA and other veteran advocacy groups forced the VA to shift its policies to become more receptive and sensitive to the issues that would later become known as PTSD. Despite the unresponsive attitude of the United States government and the VA system, veterans were able to secure treatment for themselves through their own selfdetermination. Through the construction of rap groups and through veteran activism, Vietnam veterans successfully brought their needs to the attention of the public. This laid the ground work for the acknowledgement and much of the modern treatment of PTSD. *** The Vietnam War was one of the costliest engagements in modern American history. The war cost millions of dollars, nearly 60,000 American lives, and spanned a decade. However, one factor that cannot be measured with statistics is the psychological pain that 44 Jones, Post-Traumatic Stress, 96. Jones, Post-Traumatic Stress, 96. 46 U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. “Vet Center,” http://www.vetcenter.va.gov/(accessed October 21, 2012) 47 U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs 45 19 combat induced on the young American soldiers who were sent to fight for their country. Upon returning home, many young Americans did not receive adequate emotional support from family, friends, and society at large. In retrospect, we understand that this factor plays an integral role in the development of PTSD symptoms. Without help, many veterans went on to commit violent and heinous crimes, finally bringing the issue of mental illness brought on by traumatic experience into mainstream society. The Veterans Administration had become very well equipped by the 1970s, providing veterans with an array of facilities to enable them to recover from their physical wounds. However, the VA system of the 1960s and early 1970s lacked adequate mental health facilities and seemed unwilling to accommodate the demands of veterans. Rather than continue to suffer in silence, veterans took it upon themselves to solve their psychological issues. Initially forming rap groups to aid in their healing, these groups evolved into much larger organizations. Organizations such as the VVA provided veterans with the means to enact change in government. Additionally, many veterans took it upon themselves to work from within the government to secure rights for their fellow comrades. Veteran activism was successful as it pushed the VA and the US government in general to acknowledge the needs of veterans thus securing for themselves treatment for their PTSD. 20 Bibliography: Primary Sources: Books Figley, Charles. Stress Disorders Among Vietnam Veterans. New York: Brunner/Mazel, Inc., 1978. Periodicals Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, California,1967-1979. New York Times, New York, N.Y., 1970-1975. Journal Articles “A Scientific Look at Vietnam Veterans Science News.” Science News 101, no. 3 (January 1972): 39 Arlene, K. D. “Normal mental illness and understandable excuses the philosophy of combat psychiatry.” The American Behavioral Scientist 14, no. 2 (1985): 167. Dobbs, D., & Wilson, W. P. “Observations on persistence of war neurosis.” Diseases of the Nervous System 21 (1960): 686-691. Lewis, C. N. “Memories and Alienation in the Vietnam Combat Veteran.” Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 39 (1975): 363-369. Leventman, Seymour. “Official Neglect of Vietnam Veterans.” Journal of Social Issues 31, no. 4, (1975): 175. Mayfield, D. G., & Fowler, D. R. “Combat plus twenty years: The effect of previous combat experience on psychiatric patients.” Military Medicine 134, no. 10 (1969): 1348-1354. Rivers, Caryl. "Veterans of the Wrong War: The Vertigo of Homecoming." Nation 217 (1973): 646649. Robinson, John W. “A Chance for the Mentally Ill.” The Science News-Letter 71, no. 17 (1957): 266. Strange, R. E., & Brown, D. E. “Home from the war: A Study of Psychiatric Problems in Vietnam Returnees.” American Journal of Psychiatry 127, no. 4 (1970) 488-492. 21 Strange, R. E. “Psychiatric Perspectives of the Vietnam Veteran.” Military Medicine 139, no. 2 (1974): 96-98. Solomon, G. F., Zarcone, V. P., Yoerg, R., Scott, N. R., & Maurer, R. G. “Three Psychiatric Casualties from Vietnam.” Archives of General Psychiatry 25, no. 12 (1971): 522-524. Secondary Sources Books Arnoldt, R. P. After the war: Post-traumatic stress disorder and the Vietnam veteran in american society. Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago, 2003. Binneveld, J.M.W. From Shell Shock to Combat Stress: A Comparative History of Military Psychiatry. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1997. Herbert, Hendin. Wounds of War: The Psychological Aftermath of Combat in Vietnam. New York: Basic Books, 1984. Jones, Edgar. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. New York: Psychology Press, 2005. McCallum, Jack E. Military Medicine: From Ancient Times to the 20th Century. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2008. Shay, Jonathan. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. New York: Maxwell Macmillan International, 1994. Shepard, Ben. A War of Nerves: Soldiers and Psychiatrists in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001. Journal Articles Bentley, Steve. "A Short History of PTSD: From Thermopylae to Hue Soldiers Have Always Had A Disturbing Reaction To War." The VVA Veteran: The Official Voice of Vietnam Veterans of America, Inc. (March/April 2005). 22 Egendorf, Arthur. "Vietnam Veteran Rap Groups and Themes of Postwar Life." Journal of Social Issues 31, no. 4 (1975): 112. Keane, Terence, W. Own Scott, and Gary A. Chavoya. "Social Support in Vietnam Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Comparative Analysis." Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 53, no. 1 (1985): 95-102. Lipscomb, Carolyn. "Lister Hill and his Influence." Journal of the Medical Library Association 90, no. 1 (2002): 109-110. “Post traumatic stress disorder and politics.” Health and Stress (2007): 1-11. Robinaugh, Donald J. "Understanding the relationship of perceived social support to post-trauma cognitions and posttraumatic stress disorder." Journal of Anxiety Disorders 25 (2011): 1072-1078. Wood, Paul. "Da Costa's Syndrome (or Effort Syndrome)." British Medical Journal, (1941). Jones, Edgar. "Shell Shock and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Historical Review." American Journal of Psychiatry 164 (2007): 1641-1645. Other Sources Jones, B. M. “Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in United States Legal Culture: An Historical Perspective from World War I through the Vietnam Conflict“ PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1995. Silver, S. M. “Post-traumatic stress reaction and family of creation variables among vietnam veterans” PhD dissert., Temple University, 1982. United States General Accounting Office, Va Hospitals: Issues and Challenges for the Future. 1998.