Medical Software Industry Association

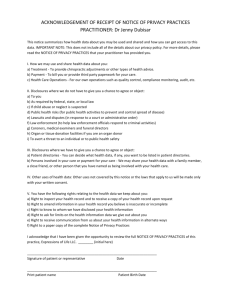

advertisement

Medical Software Industry Association Comments on the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Records System — Enforcement Guidelines for the Information Commissioner 2012 “Health Records and medical privacy is undoubtedly one of the most controversial, most complicated and at the same time most important of the privacy issues currently facing Australian society.”1 The Medical Software Industry Association represents over 120 of Australia’s medical software companies, and welcomes the Draft enforcement Guidelines for the Information Commissioner. The MSIA recognises that “…the Australian public considers their health records to be particularly sensitive….”2 Privacy is a fundamental human right and personal health information can be some individual’s most sensitive data. Protection of privacy is crucial if Australian is to realise the benefits of co-ordinating care and providing vital health data where and when it is needed through medical software systems. Clearly Australians must have confidence in a clear and strong privacy framework which identifies how data is to be collected and used and provides clear rules for compliance and enforcement if they are to take advantage of new technologies which will both improve their access to and ability to use health data effectively. These are the reasons why privacy protection is of vital concern to the Medical Software Industry Association. The Draft Guidelines clarify the operation of the current privacy framework and the penalty and enforcement provisions in the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) and the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Records Act 2012 (Cth), Personally Controlled Electronic Health Records Regulation 2012(Cth), and PCEHR Rules 2012 (Cth). This is of significant benefit to all parties accessing or participating in any way with the PCEHR System. In the absence of adoption to date of some the relevant 295 recommendations in the 2008 Australian Law Reform Commission report For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice, the Draft Guidelines provide for enforcement, data breach notification and simplify the enforcement procedures. The flexibility of the approach demonstrated in clause 8 (Undertakings) and Clause 9 (injunctions) displays a calibrated response to multi-faceted privacy issues. The MSIA commends the OAIC for this and makes the suggestions of possible enhancements to the Draft Guidelines for consideration. 1 L.Lim, “Electronic Health Records and Medical Privacy”, (2001) Cyber L Res 15. 2 Past Attorney General, the Hon. Daryl Williams QC speaking on the introduction of the Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill 200 MSIA 2012 Page 2 of 11 CONTENTS The Role of the System Operator and How the Guidelines are to apply to the System Operator. 4 Information and Resources available to the OAIC to investigate alleged technical aspects of breaches. 8 The possibility of Public Interest Determinations. 11 MSIA 2012 Page 3 of 11 1. The Role of the System Operator The OAIC in its submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs3 referred to the fact that s.14 of the PCEHR Bill4 should have a note stating that the System Operator is subject to the Privacy Act and the Privacy Act should be amended to include System Operator under the PCEHR Bill. These amendments do not appear to have been followed. Consequently it is not clear whether any future System Operator prescribed by the PCEHR Regulations would be subject to the Privacy Act,5 although clause 4.8 of the draft guidelines makes it clear that the current system operator is subject to the PCEHR Act and the Privacy Act. The reason for this concern is that the System Operator is probably the largest participant in the PCEHR system, and has significant powers and control over the data in the system, the operation of the system and the interface through which participants access the system. Consequently, should there be any significant, severe, large scale or systemic breach of the privacy in the PCEHR System it will almost certainly be a result of some technical or process failure of the system operator. This clearly limits the OAIC and the Commissioners ability to respond to complaints or initiate audits of the information handling processes. Some of the specific areas which could result in privacy breaches which may be beyond the reach of the Commissioner include the following: S.56 of the PCEHR Act determines that data can be placed on the Register by the System Operator for administrative purposes or as specified in the Rules. This could result in a decision to incorporate data on a Register in respect of a consumer or other entity that warrants examination for the Commissioner. S.11 of the PCEHR Act binds the Crown but does not make it liable for any offence or pecuniary penalty. Consequently, in the event of a breach by Agencies or the System Operator the Commissioner has no power to make determinations, injunctions, and undertakings or enforce data breach notifications. At this point it should be noted that one of the most enduring complaints about privacy protection in Australia is the fact that to date the penalties have been 3 Inquiry into the provisions of the PCEHR Bill and a related Bill January 2012, Timothy Pilgrim Australian Privacy Commissioner 4 Subsequently passed and No. 63, 2012 Personally Controlled Electronic Health Records Act 2012 (Cth) 5 Note: the Explanatory Memorandum to the PCEHR Bill p.35 said the System operator would be subject to the Privacy Act, but this was not inserted into the Act. MSIA 2012 Page 4 of 11 largely limited to naming and shaming, as the Privacy Act as it stands, does not allow the Commissioner to impose a sanction if it investigates its own motion. The ability to enforce privacy law is essential to signify the importance of privacy compliance and “give an even greater incentive to take their responsibilities seriously”6. The fact that the party with some of the greatest responsibilities in the PCEHR operation is not subject to any penalty or enforcement proceedings, denigrates the importance of both the principle of privacy and the power of the Commissioner to assist in the privacy protection of Australians. The MSIA members depend on the confidence of all Australians including in the security and privacy of their data and hope that the Guidelines are in future able to be extended should the Legislation and Rules be amended to bring the System Operator within the scope of the Draft Enforcement Guidelines. S. 50 of the PCEHR Act provides a requirement that a registered repository operator, a registered portal operator or a registered contracted service provider must provide information in the consumers PCEHR to the System Operator. The Commissioner is not able to regulate the System Operator; consequently there is a risk of more data than is strictly necessary or within the reasonable contemplation of consumers, being provided to the System Operator. In this regard the OAIC’s submission in respect of the Rules7 should be noted as it did countenance the fact that in the course of identifying parties it was critical that the System Operator did not collect more data than was necessary and that the System Operator should comply with the Privacy Act and the Information Privacy Principle 1.1. It is hoped that in the absence of consumer education in this regard or enforcement powers by the Commissioner that the OAIC can undertake community education to avoid breaches without penalty which will have a negative effect on the uptake of the PCEHR system. S.63 of the PCEHR Act provides that the System Operator can request collection, use or disclosure of information in a consumer’s PCEHR to perform a function or exercise a power. 6 Privacy Law Reform: Challenges and Opportunities, Tim Pilgrim, Presentation to Emerging Challenges in Privacy Law Conference, 23 February 2012. 7 Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record System: Proposals for Regulations and Rules April 2012 Submission by Timothy Pilgrim Australian Privacy Commissioner p.12 MSIA 2012 Page 5 of 11 There was not detail of what these functions or powers may be detailed in the Rules. Again the fact that the System Operator appears impregnable, means that a consumer which has consented to have sensitive data uploaded for his or her healthcare, may be unaware in giving this consent , that the System Operator has these powers and that there is no recourse if there are negative impacts for the consumer. The MSIA realises that it is beyond the scope of the Commissioners powers in the Draft Guidelines but wishes to register its concern. S.73A of the PCEHR Act (Information Commissioner providing detail of investigations to System Operator) and s. 107 of the PCEHR Act (Annual Reports by System Operator) both provide possible conflict situations. For instance the Commissioner may provide information about aspects of performance issues by the System Operator to the System Operator and the System Operator must report on complaints to the System Operator about the System Operator. This may not instil confidence in the final exercise of power, as it could appear to be selfregulatory where the party being reported on provides the report. It could be said to result in “…supervision of the sheep by the wolves, for the benefit of the wolves …”8 The OAIC stated in its submission in respect of the PCEHR Concept of Operations, that it is appropriate for the System Operator to hear complaints but not be final arbiter. Management and rule setting functions should be separate from accountability and oversight functions.9 Whilst the MSIA appreciates the Commissioner can only make Guidelines about what it is given power over, there is concern that by not giving an overall right and obligation by the Commissioner to report on the System Operator, public confidence in the privacy may be diminished. S.94 of the PCEHR Act provides that either the System Operator or the Information Commissioner may accept undertakings from people in respect of the Act. How will the Commissioner and the System Operator be able to ensure that there is transparent and comprehensive reporting of these undertakings when both parties are given responsibility. 8 Roger Clarke, “Privacy as a means of Engendering Trust in Cyberspace Commerce” University of New South Wales Law Journal 24 (1) 2001 290, 295. 9 OAIC PCEHR Concept of Operations Submission 2011 at paragraph 126. MSIA 2012 Page 6 of 11 It would seem preferable for undertakings in respect of privacy issues to be given solely to the Commissioner. It would be productive to avoid the situation where parties “chose” their arbiter on the basis of an expectation of a better outcome. MSIA 2012 Page 7 of 11 2. Information and resources available to Commissioner to investigate alleged technical breaches of privacy a. It appears that technical breaches by repository or portal operators for instance S.79, will be subject to the Commissioners powers under S.79. It is suggested that this type of investigation may fall outside the scope and expertise of the privacy regulator and affect appropriate investigation and enforcement. The Medical Software Industry is keen for total confidence by Australians in respect of technical aspects of the PCEHR and encourages robust supervision. Has the Commissioner the resources to assess if parties are entitled to be registered (S.76)? Has the OAIC the technical resources to make determinations pursuant to Guideline 8.1 in respect of technical assistance on relevant facts and desirable technical outcomes for undertakings? It is critical that the Commissioner is given sufficient resources in this regard. b. S. 75 of the PCEHR Act provides terms of data breaches. The suggestion previously made by the Privacy Commissioner10 is that security and access frameworks, such as the one developed by NeHTA in its National eHealth Security and Access Framework be implemented into the legislation to enhance the data security framework and expectations of participants. Clearly without these guidelines being stated in the legislation, it makes the role of the Commissioner in enforcing the framework more ambiguous. Security and access are key to privacy. The OAIC suggestion that a version of the National Privacy Principle 4.1 Schedule 3 of the Privacy Act 1988 be included into the Rules was not adopted11, namely: 4 Data security 4.1 An organisation must take reasonable steps to protect the personal information it holds from misuse and loss and from unauthorised access, modification or disclosure. 4.2 An organisation must take reasonable steps to destroy or permanently de-identify personal information if it is no longer needed for any purpose for which the information may be used or disclosed under National Privacy Principle 2. The MISA hopes that the Commissioner is enabled in the future to make enforcements based on this fundamental principle. 10 11 Senate Submission ibid p.13 OAIC Submission on the PCEHR Rules April 2012, p.3 MSIA 2012 Page 8 of 11 c. The MSIA has read with interest the Privacy Commissioner’s submission in respect of the PCEHR Rules12 which govern the terms of reference for the Draft Enforcement Guidelines, and considers them germane to this submission: 5.6 Technical specifications The OAIC is concerned that the technical specifications that will apply to healthcare provider organisations, repository operators, portal operators and contracted service providers will be published as a schedule to the PCEHR rules. Clause 78 of the PCEHR Bill provides that a civil penalty may apply if a person that is, or has at any time been, a registered repository operator or a registered portal operator contravenes a PCEHR rule that applies to the person. Under cl 79 of the PCEHR Bill, the Information Commissioner is the only person who may apply to a Court to seek the application of a civil penalty order. The issue for the OAIC is that technical specifications may fall outside the scope of privacy regulation, which may limit the Information Commissioner’s ability to effectively investigate a possible breach and seek a civil penalty order. For example, if an entity does not comply with a rule in the schedule relating to a particular software interoperability specification, but no data breach or interference with privacy has resulted, the Information Commissioner may not have the appropriate powers or expertise to investigate and remedy the contravention. For this reason, the OAIC recommends that the technical specifications should not be included in the PCEHR rules. The OAIC suggests that technical specifications could be better regulated by the System Operator in a separate document such as in the terms and conditions of participation in the system. It is noted in the Explanatory Statement Issued by the Minister for Health on the PCEHR Rules, that the Independent Advisory Council was consulted on the PCEHR Rules 2012 on 19 July 2012 and no amendment of the Rules was found necessary. Consequently, the proposal by the Commissioner was not adopted and the Commissioner is responsible for enforcement proceedings for technical breaches. The MSIA notes that “the OAIC considers that identity verification is critical to the security and integrity of the PCEHR system”13 and can see that there are complex technical errors which could occur to severely compromise an individual’s privacy and adversely affect clinical outcomes. The kind of error that is described in the boxed example (over) not only illustrates that a relatively small error in any part of the system may have a serious impact for individuals, but the error is likely to cascade through systems, “Data Profiles have a potential to magnify and endlessly reproduce human error,”14 or no doubt, technical issues as the case may be. 12 Ibid at p.13 Ibid at p.12 14 Kirby M, “Privacy in Cyberspace” (1998) 21 (2) UNSWL 13 MSIA 2012 Page 9 of 11 EXAMPLE: Anita Lemming obtained her healthcare identifier and wished to take part in the PCEHR system as she had complex healthcare and saw benefits in sharing data on these co morbidities with her various healthcare providers. Her healthcare identifier was 1234567890123456. Peter Smith also wished to be a part of the system as he was chronically ill and obtained his healthcare identifier 1234567890123458. An error occurred in either the patient management system or in the PCEHR and merged the two records together, and as a result the wrong IHI was used to retrieve clinical data from the PCEHR. This resulted in Anita's clinical records actually displaying Peter’s health data. How does the Commissioner unravel the technical issues surrounding what amounts to a devastating breach of public trust in the integrity and protection of both parties’ personal and health data? It is hoped that the OAIC is provided with appropriate resources to investigate such breaches of this sort which will otherwise affect the success of the PCEHR System. MSIA 2012 Page 10 of 11 3. Public Interest Determinations The MSIA considers that the ability for the Commissioner to make Public Interest Determinations on all privacy and security aspects of the PCEHR operation pursuant to the Guidelines would be of great value to the community and industry. This would be of particular value over the next months’ whilst the PCEHR is emerging and issues are being encountered. Such a power would assist in making the issues transparent and the balance between healthcare and privacy, and ensure that the public is given a balanced and objective perspective on the privacy and security issues surrounding the PCEHR. MSIA 2012 Page 11 of 11