HUMAN SACRIFICE: Human sacrifice (defined as the killing of a

advertisement

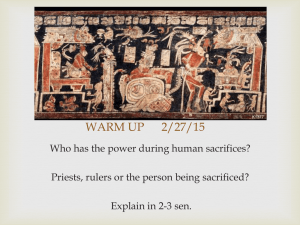

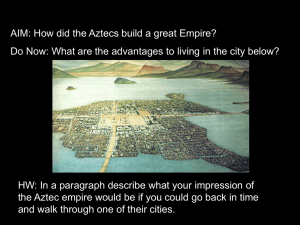

HUMAN SACRIFICE: Human sacrifice (defined as the killing of a human for the purpose of dedication to a divine or semi-divine being) seems to have been a reality of the ancient Mediterranean world, although the frequency and extent of the practice is heatedly debated among scholars. Since the SACRIFICE of a human would have been the most extreme gift one could make to a god, it was in various contexts celebrated or reviled, but frequently featured in literature and histories. Three separate categories of human sacrifice in the cultures of the Mediterranean may be utilized to clarify the difficulties in understanding this phenomenon: (i) the sacrifice of a highly-valued human by a king or other leader, usually to avoid some catastrophic outcome; (ii) the sacrifice of prisoners taken in war, often as thanks for victory; (iii) the regular, recurring sacrifice of humans as part of a religious cult. The human sacrifice made by a king or other leader (i) is perhaps the most widely established form of human sacrifice thought to have been practiced, though it would have occurred only under rare circumstances. The sacrifice in these cases is typically made under duress—famous examples include the king of Moab who sacrifices his son on the walls of his capital city to escape an Israelite siege, or the story of Agamemnon’s sacrifice of his daughter, Iphigenia, to obtain good omens for his voyage to TROY. The trope of a leader giving the life of his own child in order to save those whom he leads is a powerful literary device, but perhaps also reflects a realistic scenario of last resort. The second type (ii) involves a scenario in which the value of the offered human lives would presumably be less (to those conducting the sacrifice) than in the first scenario. For example, HERODOTOS (the earliest Greek source to discuss human sacrifice) describes the Scythians as sacrificing one in every hundred of their prisoners of war to the god Ares. The sacrifice of humans as part of a regular, recurring religious cult (iii) is the most controversial of the three. Many ancient accounts seem designed to shock their readers: Herodotos tells the story of the Massegetae (a nomadic tribe sometimes associated with Scythians and the Iranian plateau), who reportedly kill their elderly members as part of a larger sacrificial ceremony, boil their flesh, and offer this dish to relatives to consume. Others attest to the association of human sacrifice with a particular festival or place; such as on Mt. Lykaion, in Arcadia, Greece. In the latter case, ongoing excavations have traced the use of the site to 3000 BCE, and osteological studies may have more to say about the possible sacrifice of humans. Regularly occurring child sacrifice is opaquely referenced by several biblical texts: the story of Abraham’s interrupted sacrifice of his son is often read as a prohibition of human sacrifice as an appropriate gift to god; as are the biblical warnings against the worship of a god called MOLECH. The Phoenicians have been particularly singled out by authors ancient and modern as practicing human sacrifice as part of a regularly occurring religious ritual. In their case, the accusations involve the sacrifice of infants, and especially one’s own child. No evidence for this practice exists in the Phoenician Levantine “homeland.” But the discovery of ten Mediterranean Punic cemeteries containing the cremated remains of infants buried in ceramic vessels (frequently referred to by scholars with the Hebrew term “TOPHET”), and often accompanied by inscribed or painted stelae, has suggested to some that the practice may have been a reality in CARTHAGE and other Punic sites. No feature of the evidence for human sacrifice in Punic contexts is uncontested. Because archaeological excavation has produced human remains, it was hoped that these would reveal whether the infants were miscarriages, still-births, or other natural deaths, or whether they were born healthy and sacrificed afterwards. However, aside from the difficulties associated with identifying pre- versus post-natal features under ideal circumstances, the infant skeletal remains underwent shrinkage during the cremation process and calcination due to the sandy soil in which they were buried. The inscribed stelae which mark graves at seven of the ten burial sites are formulaic in nature, and utilize specialized Punic vocabulary that is not found in clear contexts in other extant texts. Finally, none of the twenty-four ancient authors writing in Greek or Latin (dating from the 5th c. BCE to the 5th c. CE) who discuss the practice of human sacrifice among people of Phoenician or Punic origin claims to have witnessed the practice first-hand, and many seem to be using them as a stock example of a long-ended barbaric or aberrant practice. Accusations of both adult human and child sacrifice (as well as various forms of cannibalism) were also leveled at early Christians, continuing a long tradition of using this trope to alienate or “other” a particular religious group. SUGGESTED READING: Azize, Joseph. “Was there regular child sacrifice in Phoenicia and Carthage?” In Gilgameš and the World of Assyria: Proceedings of the Conference Held at the Mandelbaum House, University of Sydney, 21-23 July, 2004 (J. Azize and N. Weeks, eds.), 185-206. Peeters Publishers, 2007. Hughes, Dennis D. Human sacrifice in ancient Greece. Routledge, 1991. Rives, J. “Human Sacrifice among Pagans and Christians.” In The Journal of Roman Studies 85 (2010): 65-85. H.D.