Barbara D. Sanders

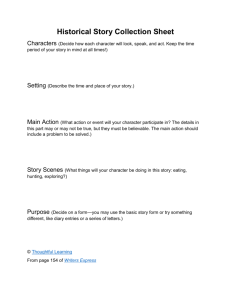

advertisement