A Reflective and Strategic Profession in the Further Education Sector

advertisement

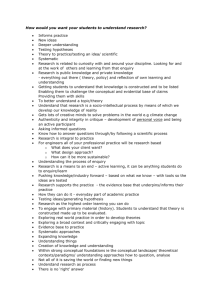

A Reflective and Strategic Profession in the Further Education Sector Teachers in Further Education have a vital role to play in an education system that is serious about supporting lifelong learning and providing opportunities for all learners to reach their economic and social potential. They work in a sector which is constantly changing, reacting to the needs of employers, policy-makers and students and so it is vital that they themselves are resilient, creative learners. It is evident from the Learning to Learn in FE project that there are key factors and conditions that support teachers to be more effective, more flexible and more resourceful. These factors have an impact on teachers’ performance, their motivation and their desire to stay in the profession. Colleges can become learning communities at an organisational level, where senior managers, teachers and learning support staff are all exploring effective teaching and learning. Critical listening enables this to be shared across teams A different model of staff development is needed for this to take place: the focus is on reflection and metacognition so that content knowledge and skills are embedded in practice. Key techniques include systematic enquiry and coaching. The collaborative enquiry process itself has a profound effect on teachers: making the language of learning explicit and providing a focus and rigour for teachers’ investigations. Teachers report increased selfawareness, motivation and effectiveness Colleges have had to make an investment in supporting the enquiry networks, both within and beyond the institution. The time and space needed for teachers’ learning appears to be greater than for ‘training’, though the investment is much more profitable The impact of the learning community in which every member of staff has the opportunity to see themselves as a learner goes beyond the staff team. Reflection, enquiry and personalisation become part of classroom practice, giving students a parallel experience. The development of confident, capable lifelong learners depends on the teachers themselves having awareness of their own learning, motivation and the range of pedagogies which can support this. High quality teaching and learning is fostered by teachers who can integrate content knowledge, skills and dispositions COLLEGES AS LEARNING ORGANISATIONS The culture of learning in FE is complex: simultaneously trying to give students choice and independence while catering for a diverse group of learners, many of whom lack the skills to be active participants in how they are taught. Students do not enter college as fully formed learners ready to take responsibility at this level. Rather, they develop such an identity slowly and over time as a result of their cumulative experiences in college. The challenge expressed in these case studies is one of cultural change. Colleges in the project have responded to this challenge by encouraging staff to undertake enquiry projects that make the language of learning explicit and which give multiple opportunities for learners and teachers to discuss and reflect on the process and purpose of learning. It is only through ‘moments of communication’ between teacher and student in the classroom that a new culture, geared to personal and social development rather than simple attainment, can grow and flourish. The enquiry projects have been diverse in focus, though a common aspect has been the time and space needed for teachers to reflect upon and discuss their findings. Management teams in colleges have had to be open to new ways of working, both in supporting enquiry and collaborative learning in their staff teams and to making the organisational changes that the projects recommend. They devote time and space in supporting them and the dissemination of the learning from them across their staff teams, although clearly they believe this is a worthwhile investment: “This and the other L2L projects have gained favourable attention from the college senior management team and it is hoped to embed a “Learn to Learn” culture college-wide.” An exploration of the gradual development of a culture of excellence in a college (1) has found that it is dependent upon the space devoted to reflection within the staff team. Two cycles of enquiry looking at inspection, teacher development, coaching and feedback highlighted three key interlocking elements. Firstly, the use of a common language to talk about learning which encouraged a focus on motivation and metacognition: “I get inspired by watching teachers teach or listening to them describe what they do and then I want to go and try it out.” Secondly, putting this into practice through reflective cycles of coaching encourages teachers to own and embed their understanding: “As the clarity about his own evaluation of his practice gradually emerged, so did what the actions that needed to work on.”. Thirdly, the enquiry process itself provides a structure and a standard of evidence which encourages teachers to examine why they make particular decisions about teaching and learning. PROFESSIONAL ENQUIRY Enquiry is important at all levels of the project. It is a questioning process in which all participants in the project are involved . This can be formal or informal, evidenced in a desire to explore different aspects of learning to learn and what it means to each individual. There is also a common language about enquiry: an explicit understanding of the need for clear questions, rigorous methods of evaluation and the responsibility to communicate findings across the community. The enquiry process is fundamentally shaped by each teachers’ identification of an immediate problem to be explored, one which has an intrinsic value based on the benefits to all of exploring it and about which enough can be said so that the problem can be formulated and worked on. This gives teachers (and learners) a voice in the ongoing conversation about research and ‘what works’ in teaching and learning. The evidence from Learning to Learn suggests that teachers develop a more robust and critical stance through the process of their own research, as well as a vocabulary and confidence to access the wider literature. Meanwhile, in classrooms and beyond them, many teachers have creatively seen a way to transfer their own learning experience to students. Based on a college survey that had pointed to shortcomings in the induction process across the college, a team in Art and Design (2) decided to adopt an open point of enquiry. Instead of presenting students with a summary from the teachers’ perspective and asking them to agree or disagree, it was thought that by providing the learners with a ‘blank canvas’ they could draw a picture of what their experience of induction had been like for them and, more significantly, what it might or should have been. In this way it was hoped that a true picture of what learners required from induction would emerge (as opposed to a series of choices made by the teachers but not necessarily either relevant to or prioritised by the learners). This emphasis on exploration and following a genuine curiosity is a key characteristic of enquiry. In the second cycle key issues raised by the students were addressed and the overall induction experience re-evaluated. However, although there was good evidence that students were more satisfied with induction and that retention and results had improved, the team remained reflective and critical: In some ways these figures are difficult to interpret; after all, if changes have been made for the better one might take them for granted and not value them as much as if they are absent! Nonetheless, an overall picture of a more positive, confident and selfsufficient group of learners emerges DEVELOPING A COMMUNITYOF ENQUIRY In a professional learning environment all learning needs to be given equal status so that teachers can see beyond their own curriculum context and be confident of their own professional knowledge. This could be considered as risky without the systematic enquiry process underpinning the perspectives that are shared. The enquiry process in Learning to Learn had provided rigour to the learning and supported the communication process. It does mean that the sharing of experiences, the process of critically listening to contributions and the need to signify equivalency of each contribution is central. The spin-off from this is that teachers use these democratic and collaborative learning ideas in their relationships with colleagues and students. This allows a crucial shift to take place in colleges, where authentic communication of the purpose of each learning opportunity allows both teachers and students to take on a degree of ownership and responsibility. “The biggest resource that I have is within me and the time and space that I commit to reflecting on my practice.” Learning to Learn colleges encourage everyone who is part of the learning community to see themselves as learners. The ability to recognise one’s own strengths and weaknesses forms the basis for being part of a flexible learning community that takes account both of the value of difference and of the necessity to learn some things in specific ways, bridging personalisation with core skills. A pair of case studies focusing on developing the skills of Learning Support Staff (3) made use of the common language of the project. The aims, to Encourage ongoing reflection on previous and current learning. By investigating personal learning and learning theories creating a new readiness for learning. Through raising learning awareness improve learning resourcefulness leading to learning resilience through building self confidence and understanding. have enabled staff to see their own learning and students’ learning as part of a parallel process. “I can identify the emotions my learners are going through and help them overcome it” “it did make me aware of how much learning we do in our everyday lives” Implications We have a range of evidence that teachers in FE can become the creative producers of pedagogical knowledge relevant to their context, rather than the passive consumers of ‘training’. In order to make this shift it is necessary for colleges to look to a new model of staff development, one which requires a longer term investment. Rather than spending large sums on ‘events’ and ‘experts’, colleges have found a much greater return by supporting teachers to have regular time and space for investigation, reflection and engagement with a community of enquiry. Teachers use this time to undertake cycles of inquiry, taking on the feedback of colleagues and students and becoming more confident of the weight of evidence for their approaches to teaching and learning. The focus is on the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of learning but not at the expense of the ‘what’. In enquiry, as in reflection and coaching, the emphasis is on the integration of these understandings. This is achieved by teachers designing their own research questions: teachers better than anyone recognise the importance of their students achieving mastery over the content of the courses as well as mastery over their own motivation and metacognition. The enquiry process is dependent upon talk: discussions with colleagues and the responsibility to share findings across teams, locations and, through the wider project with colleagues in nurseries, primary, secondary and special schools, colleges and university departments. This talk requires a common language for learning that enables teachers to become aware of how they think about their practice. As teachers become proficient in dialogue in their own learning community: characterised by authentic questions that have no pre-specified answer, they become more confident in changing the way they talk to their students about their learning, leading to a gradual and significant shift in classroom exchanges. Talk becomes a tool by which thinking and understanding can be shaped and developed. The enquiry process and the change in learning culture in colleges which it permits leads us to a better understanding of professional learning. Strategic, reflective and metacognitive thought is what we not only need to recognise in teachers’ learning but also to privilege in discussion of teachers’ work. PRACTITIONER ENQUIRY Learning to Learn in FE participants have been supported in completing two connected cycles of enquiry over the duration of one and a half academic years. The individuals or teams were encouraged to find enquiry questions which fit with their own and their subject’s priorities for teaching and learning and to think about explorations that were manageable in relation to workloads and course commitments. The locus of control for the research topic remained very much with participants. This was felt to be very important as it allows individual judgements to be made about what questions need to be asked about teaching and learning and how they can best be researched. Data gathered during and between the face to face days, include audio-recording of discussions and collection of documents created during small group reflective tasks. Case study methodology was used as the basis for output. To ensure that the individual enquiries were not overly descriptive participants were encouraged to collect at least three types of data including at least one piece of quantitative and one piece of qualitative data. In addition, in order to facilitate generalisation from the case studies, further exploration and within- and cross-sector analysis by the project team employs a variablebased analysis approach as well as cross project data collection tools used to triangulate case study based findings. Analysis of the cases reveals common themes and trends to be explored. Critical reflections on the pedagogical and enquiry process were also collected and findings validated using explicit feedback loops within the project structures and organisations. Across all feedback and outcomes transparency and a collaborative ethos were fore-grounded with the objective of producing and translating new knowledge about teaching and learning. CASE STUDIES 1. Morgan, J. (2009) Does Internal Inspection Raise Standards? Morgan, J (2010). How can teachers be helped to move their practice towards excellence? 2. Young, M and Paget, T. (2009) Induction as a Tool for Developing Self-Directed Learning Young, M and Paget, T. (2010) How can Induction Facilitate Independent Learning Skills? 3. Thornton, T. (2009) Facilitating Reflection about Learning with Learning Support Staff Thornton, T. (2010). Supporting Learning Support Staff to Reflect on their own Learning REPORTS Wall, K., Hall, E., Baumfield, V., Higgins, S., Rafferty, V., Remedios, R., Thomas, U., Tiplady, L., Towler, C. and Woolner, P. (2010) Learning to Learn in Schools Phase 4 and Learning to Learn in Further Education Projects: Annual Report, London: Campaign for Learning ARTICLES Hall, E. Towler, C. and Wall, K. (Under review) What does teachers’ collaborative learning look like? : using mapping in Nvivo to reflect the experience of Learning to Learn. Educational Action research Journal Towler, C., Woolner, P. & Wall, K. (In press). Exploring Teachers’ and Students’ Conceptions of Learning in Two Further Education Colleges. Journal of Further and Higher Education Towler, C., Wall, K., Woolner, P., Toyne, L., Mobaolorunduro, P., Davison, G., Pamplin, M. & Britton, D. (under review). Shaping FE culture at the sharp end; practitioner enquiry at two UK colleges, Continuing Professional Education