Verbatim 4.6 - UMKC Summer Debate Institute

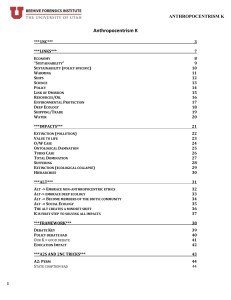

advertisement