Violence and Feminism Examined in the Roller

advertisement

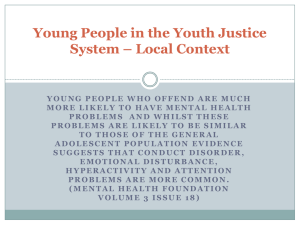

Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby Bruised Babes: Violence and Feminism Examined in the Roller Derby Subculture Eliza Harper Portland State University 1 Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 2 Abstract Though Roller Derby is a sport that thrives on excessive use of violence. The purpose of this research is to examine the Roller Derby culture in depth and fully understand the violent and aggressive attitudes and ideologies that are perpetuated through this subculture. This research aims at uncovering the true effect this subculture has on its participants and how society as a whole sees their behavior. Extensive analysis on contemporary feminist literature as well as ethnographic research can explain whether this subculture is an appropriate outlet for women to take out their aggression of systematic sexism or act as theater for women to play outside their assigned gender roles. The research attempts to show how identifying with this subculture might make participants have skewed ideas of what feminism is and how violence is justified under the idea of female autonomy. Through my ethnographic research of this subculture, this paper intends to show how this subculture perpetuates violence that has the potential to hurt the very feminist ideologies that they promote. Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 3 Roller Derby is seen as an appropriate sport for the average woman to get her aggression out, but the violence associated with the sport perpetuates the idea that violence is OK, even in women. A subculture affiliated with violence and feminism can be harmful to the very ideologies that the subculture subscribes to. It also encourages violent dominance expressed through the patriarchy and our society as a whole, which is a main theme in most feminist theories. Roller Derby has the consequence of socializing women to believe that violence is a form of women empowerment or even a jester towards gender equality. However, the violence in Roller Derby only perpetuates aggressive behavior and does nothing for the ever-evolving feminist movement except undermines it. Though Roller Derby is seen as a source of entertainment, or as a tool to cope with society’s oppressive forces, it is still a sport that thrives on excessive use of violence. Examining the Roller Derby culture in depth should lead one to understand the violent and aggressive attitudes and ideologies that are perpetuated through this subculture. This research aims to uncover the true effect this subculture has on its participants and how society as a whole sees their behavior. Is Roller Derby an appropriate outlet for women to take out their aggression of systematic sexism? Or is it a theater for women to play outside their assigned gender roles? Does the violence associated with Roller Derby perpetuate dominating ideals associated with the patriarchy and male dominance or is it a satire of violence expressed in sports in general? Answers can be found through analyzing aggressive behavior and feminist identities in the Roller Derby culture, as well as uncovering the true attitudes Roller Derby participants have about the violence that is expressed through their sport. By researching content analysis Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 4 and ethnographic studies of this subculture, one can see that this subculture perpetuates violence that can hurt the very feminist ideologies that they promote. When stepping into the roller rink that the local Portland Roller Derby team practice and compete in, one can see the images of violence before the game even starts. Lining every wall of the arena are photos of past games from over 10 years, each image bloodier than the next. These were photos of women essentially beating each other up, pulling hair, and even an action shot of a woman skating over another woman’s hand. One might feel uncomfortable around such grotesque images of violence, yet this is a skating rank families go to and the community supports. When violence in video games, movies, and the media are argued to be the root of violent behavior in others, one would think that violence in sports, like roller derby, would be to blame as well. However, violent sports are rarely ever to blame for violent behavior, and with a sport like roller derby, violence is not thoroughly analyzed because it is backed up by feminist ideologies. But the images of beat-up women on a bloody track do not echo the morals of feminism, only the idea that violence is entertaining. To truly understand the violence expressed in the average roller derby game, one can look at the rules behind the sport. Rules are set by the Women's Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA) and are used by members of both domestic and international leagues. The “bout” (how the subculture refers to the games) consists of two 30-minute periods with about 10 “jams” (how the subculture refers to the matches) in each 30minute period. In order for a team to score a point, a “jammer” of a team needs to outskate the jammer of the other team and skate more laps around the rink. The team with the most laps wins. However, the responsibilities of the Blockers of the team are to Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 5 prevent the Jammer from passing them and making another lap. This is where most of the violence comes in: Blockers do whatever it takes to prevent the Jammer from passing them. “Whatever it takes” includes shoving, kicking, grabbing, hair pulling, and ramming the jammer against the wall or railing. All of this while on wheels, which adds another element of violence considering that getting pushed while skating is a lot more dangerous than getting shoved while just walking down the street. In order to win the game you need to be as violent and aggressive as possible, yet this is a game that’s attended by families and even children. It is almost humorous when you look at the hypocrisy of the game. Roller Derby and its subculture promote a campaign of “a sport for women by women,” yet the whole game is women physically keeping other women from getting ahead. When reading feminist literature and theory, it’s all about men physically and psychologically keeping women from being successful. Women are supposed to be the gender that shows love, compassion, and empathy as true virtues of character, yet roller derby perpetuates the idea that in order to feel powerful you must exert your power physically. Feminists have fought to end violence as an exertion of power, yet roller derby makes its members feel that it is ok all in the name of the sport. In order to understand how roller derby evolved to an all-female violent sport that it is today, one must look at the history behind it. The History of Roller Derby Roller Derby started out as a co-ed sport; in most teams men out numbered women. But in 2013 almost every Roller Derby league is all female. Within 80 years an endurance competition started by a man and originally dominated by men morphed into an all female high-contact sport. Roller derby today is the result of a relatively new sport Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 6 that changed to cater to women over time. Never in history has a sport gone through such a paradigm shift as Roller Derby has. Some say the contemporary status of roller derby gives women a foothold to claim as their own. Others claim it was made for women and women just naturally play it better than men. However, Roller Derby didn’t start to carter to women until the year 2000. The real reason Roller Derby was picked up as a sport for women was because it originally stemmed from one of the first skating contests that allowed women as participants. In 1933, in his hometown of Chicago, Leo Seltzer came up with the idea to hold endurance competitions on skates. Random people would sign up in teams and compete by skating around a track 57,000 times (roughly the length across the United States). Because of the Depression, Seltzer was able to capitalize on gamblers and athletes who felt they had no other way of earning money. The Competition allowed Seltzer to create an arena where audience members can place bets while avoid paying any athletes, except the team that wins. Eventually the contests started to become more and more popular with both men and women signing up to win the prize money. What made Seltzer’s competitions so unique is that he allowed women to compete, and even place bets, when no other arenas at that time were. Seltzer didn’t know it at the time, but his decision to allow women in his arena was the first step towards making Roller Derby a nation wide sport. As Roller Derby grew in popularity, Seltzer eventually took his teams on tour. The Skating teams went to every major city in the US, promoting the endurance test and even influencing other cities to open their own arenas. In 1938, sports writer Damon Runyon approached Seltzer and proposed some ideas that would make the competitions Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 7 more entertaining. These ideas mainly involved violence, specifically elbowing and slamming opponents into an iron rail in order to gain leverage (Rasmussen, 1999). Seltzer hated the idea; he created the contest to highlight athleticism and endurance not cheap showy tricks like pushing and shoving. But when the new rules were introduced allowing for physical contact, the crowd went wild. They loved every minute of it and the rumor of Roller Derby spread like wild fire. By 1940 everyone was talking about this new sport where everyone is shoving and punching each other on wheels just to earn some extra money. Seltzer never looked back after the audience had a feeding frenzy on the contest’ new violent edge. Eventually, rules were added to give points to teams that knocked over players. The introduction to the point system changed the whole dynamics of Seltzer’s endurance competitions to a team-on-team battle royale. The Dawn of World War II caused many of the male skaters to leave the skating leagues to enlist. This ended up being the first wave of female-dominate Roller Derby teams, creating a new market audience: housewives. Through out the 40’s and 50’s housewives were the most frequent audience members; Seltzer even started selling tickets at grocery stores and fabric shops to make it more convenient. As Catherine Mabe (2008) wrote in her book on Roller Derby history and culture “Most Women simply didn’t relate to football or baseball players of their time, and the other options for entertainment, such as movies, didn’t provide an adequate release during such trying times. But the ladies of the era could somehow envision themselves racing across the smooth track, bent low at the knees, propelling themselves forward with force of will”. 50 years later, in 2000, women-only derby teams started to form. Daniel Eduardo “Devil Dan” Policarpo was the man who started the all-girl campaign for Roller Derby. It Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 8 really started out as a gimmick, a way for him earn some extra money promoting something new and progressive. It wasn’t meant to be athletic and competitive, but entertaining and attractive. As Devil Dan said himself in a interview with New York Times, he “envisioned low lighting, quick flashes of red, blue and green, glow sticks, drummers, a cramped track, violence and microphones everywhere” (Brick, 2008). He explained how he wanted women “with tattoos, Bettie Page haircuts and guts.” Unfortunately, Devil Dan’s vision of contemporary Roller Derby also included weapons and oddly dressed clowns, which the female team captains did not find appealing. Only a year after the advent of his all girl derby teams, Devil Dan was kicked out of the leagues and hasn’t participated since. The women of contemporary Roller Derby took Devil Dan’s concept of women empowerment and ran with it, or shall I say skated off with it. These Leagues have evolved to where they are today. There are many points to take away from looking at its history that are very important in terms of understanding the image that Roller Derby culture projects. Roller derby is now a female-dominated sport (verses women’s leagues in other sports) because it stemmed from one of the first contests that allowed women to participate. Although the campaign to create an all-female roller derby league was started by a man, all women teams eventually took control of the sport entirely. The combat-style tactics of roller derby were incorporated to make the game more entertaining to viewers, not more challenging to the players. Considering the History of Roller Derby and their incorporation of physical aggression into the game, one can see that not only did violence pervert a game meant to measure endurance, but it also fed into and perpetuated the idea that violence is entertaining. This is problematic because aggression shown in Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 9 entertainment has the ability to desensitize violence in both the viewer and the participant. In this case, Roller Derby can desensitize violence, anger, and aggression in both the audience member cheering them on, and the women participating in the sport. Is this what women empowerment truly looks like? Roller Derby is problematic because it gives the impression that violence is one of the only ways a woman can feel powerful and express that power. Athletes of Violent Sports Verses Nonviolent Sports The violent level of roller derby has the potential to affect the behavior of its players outside the arena. There are many cases that show a correlation between violent sports and violent athletes, with aggressive team-oriented sports being the number one producer of domestic abuse perpetrators. At the same time, there is also a correlation between non-contact sports and expressed aggression of those athletes: the less violent the sport, the less violent the athlete. It could be said that the more physical combat a sport incorporates the more the athlete feels that physical aggression is appropriate outside the sport’s arena. Roller Derby is almost entirely a combat sport, suggesting that the physical nature of the sport has the potential to influence behavior of athletes outside the arena as well, regardless of the athletes’ gender College and Major league football players LaMichael James, Pete Carroll, Leroy Hill, Cedric Wilson, and James Harrison were all accused and tried of domestic abuse. Football players, hokey players, and boxers outnumber every other athlete when it comes to domestic abuse case. According to Mary McDonald’s (1999) research on male sports figures and violence against women, critical analysis shows that most media outlets report domestic abuse as a result of individual pathology, with sports not considered a Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 10 main factor in expressed aggression (pg.10). McDonald claims that this is the real reason behind violent athletes; lack of accountability to the sport perpetuates the idea that it’s not the sport that is too violent it’s the player. McDonald goes on to theorize that mainstream media outlets are paid off by national sports associations in order to keep sports in a positive light. As important as it is to consider the media in understanding root causes of athlete violence, research suggests that blaming dispositional attributions of the athlete for the reason behind domestic abuse is inaccurate and unverified. The first signs of this are seen in the high number of domestic abuse cases in violent sports athletes. It is completely unreasonable to see the data that correlates violent athletes with violent sports and blame it on violent people playing the sport, not the sport itself. In Collin’s book Violence: a Micro-sociological Theory (2011), he claims, “player violence is most frequent in offensive/defensive combats organized as teams rather than individuals…this fits the general pattern that violence depends upon group support” (pg.287). His research supports the theory that individual attributions of one’s character cannot be fully blamed for expressed aggression in athletes when it is the group mentality of the sport that is truly the root cause. Collins goes on to explain that the most violent sports are those played with competing teams. He theorizes that socialization of violence is fueled in the locker room and through validation found in the team. Within a team, you are supported for being violent against the other team, verses the inner dialog of one player would make an athlete of a single-player sport less likely to act violently since that socialization is not present. This is important when considering the rules behind roller derby: the sport is not only a team-on-team competition, but it is a sport that expresses violence that is Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 11 supported by the other member of one’s own team. According to Collins’ research, roller derby has all the factors that would produce a violent athlete. However, Collins’ research only covers the violence expressed in men and also mentions that gender dynamics of men are at the foundation of expressed aggression as well. It should be noted that Collins’ aim was not to claim that all athletes of these violent sports become violent. But of those who are violent, the participation of these kinds of sports is one of the main contributing factors. Lack of domestic abuse cases in non-violent athletes is evidence that speaks for itself. Individual non-combat sports including tennis, golf, and volleyball have a pattern of producing less violent athletes. For example, Boris Becker, Bernard Boileau, Roscoe Tanner, and Bill Tilden are the only professional tennis players in the Professional Tennis Association convicted of a crime. None of their crimes were violent and included charges such as tax evasion, theft, fraud, and contributing to the delinquency of a minor. We can also look at the behavior of the world’s most famous golfer Tiger Woods; though seen in a negative light because of his “sex addiction”, he has yet to show signs of violent behavior. Patterns of nonviolence can be seen in marathon bikers as well; Tammy Thomas and Missy Giove were convicted of obstruction of justice and conspiring to possess and distribute more than 100 kg of marijuana respectively. A more famous example is Lance Armstrong and his admittance to performance enhancing drugs, though he was never tried for his drug use. These examples show non-violent crimes perpetrated by non-violent athletes. It should be noted that there are exceptions to this correlation between violent sports resulting in violent athletes, especially when relating it into the sphere of female Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 12 athletes. There are a high number of cases where Baseball athletes have been convicted of domestic abuse or violent assault. Baseball does not have the level of player-on-player aggressive combat as other sports yet still produces a high level of violent athletes. There are other variables that go into the domestic abuse that are more socioeconomic in origin. In the case of baseball athletes, use of performance enhancing drugs can cause athletes to exhibit violent behavior. When it comes to behavior patterns of female athletes, there just has not been enough research. Any research that mentions expressed violence and women is solely centered on women as victims of domestic abuse. As much research and correlational findings that have been made in contemporary social research with sports and violence, almost none of it can be applicable to roller derby because it is a sport entirely played by women. The socialization and dynamics of an all female team is drastically different than an all male team. What really needs to be understood is if roller derby, or any violent sport, has the power to produce violent female athletes. One would say the evidence is in the sport itself: the rules of roller derby completely involve beating up the members of the other team. However, studies have shown that women who play sports have shown less violence than their male counterparts typically do even in the same sport. According to Joncheray and Tlili (2010) and their research on female rugby players, violence “does not express itself in a satisfying way in the women's sport, as if women authorized less tension than found in men’s sport” (pg.4). Through surveys and one-on-one interviews, Joncheray and Tlili were able to show that female rugby players show more risk-taking behavior than violent behavior when engaging in high contact sports. This research aims to prove that women don’t express nearly as much violence as men do because there is no Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 13 masculinity based tension found in all-women sports, only behavior that is deemed “risktaking” because female rugby players go into a game knowing they will be hurt, not trying to be violent and overly competitive. This analysis of risk-taking behavior verses violent behavior can be applied to roller derby, seen in the conscious choice to participate in a sport where they known they will be physically hurt. In their ethnographic research and observations, Joncheray and Tlili explain that injuries are treated differently in female sports verses male sports: In all-male sports, injuries are badges of honor and are not treated seriously unless in extreme cases (i.e. the suck it up attitude of most male athletes) while in all-female sports all injuries are taken seriously, are not encouraged, and treated with great concern by other members of the team. This observation suggests that women do not perpetuate violence because injuries as a result of violent physical contact are treated with the upmost concern, not as a bragging right. Feminism and Roller Derby When examining violence expressed by women, many contemporary feminist theories believe that violence is another way of women attempting to put themselves on the same social strata as men by behaving like men. In Kimmel’s book Guyland, he goes into detail how dominate socialization of men in almost every aspect of our social world have led women to either dress and behave to attract men or dress and behave to be more like men or equal to men (Kimmel, 2008, pg. 48). With that in mind, one can see the over abundance of violence in roller derby as women “acting like men” in an attempt to be equal to men. Disregarding Kimmel’s notions of women in a man’s world, many argue that roller derby is an outlet for women to change what it means to be a woman, not just Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 14 trying to be more like men. Peluso (2012) and her research have shown that leisure activities such as roller derby help women deconstruct and redefine what femininity is. Peluso argues that roller derby gives women the power to shape what it truly means to be a woman, not just challenging what society has deemed “feminine” or “woman-like”. Instead of roller derby being an outlet for women to act like men, is it an arena for women to act like true, unfiltered, real women. Because of the fact that the sport is organized and participated strictly by women, there are no lingering feelings of hegemonic masculinity constructing their image of how a woman should act and behave. It is very important for the feminist community to analyze and rethink the gender roles of men and women, but violence should not be justified through means of intellectual discourse of contemporary gender theory. Since the advent of feminism, violence was seen as a tool used to oppress women. Yet here we see women playing a sport where violent physical contact is the only way to win the game. As progressive as roller derby appears to be for the social equality that women fight for, it only serves as a drawback against the feminist community because of the violence it perpetuates. To further understand feminism and the feminist ideologies the Roller Derby subculture subscribes to, the differences between various feminist movements must be outlined. Just like there are different sects of religions, there is also many forms of feminism. Roller Derby falls under a category of feminist thought that justifies and even encourages aggression expressed through women. However, there are forms of feminism that have been based on theory developed years ago that have always promoted nonviolence. One would think more contemporary feminism would be peaceful and nonviolent, yet it has only become more violent over the years. Views of violence Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 15 through liberal feminism, radical feminism, and riot grrrl feminism are analyzed to explain how and why roller derby has the potential to cripple the ever-evolving feminist movement. Liberal Feminism Liberal feminism is seen as the original form of feminism, stemming from the founding of such organizations as the National Organization for Women and the National Women’s Political Caucus in the 1960’s. Through out history, women have been seen as inferior to men in almost every aspect of life and have thus been oppressed as a result of this belief. . Liberal feminists were at the forefront of anti-violence activism in order protest rape, sexual assault, and domestic abuse, as well as bring attention to these issues. Before feminism become more mainstream in the 1960’s civil rights era, this realization of sexism was called “the problem with no name”. Eventually, feminist theorists appropriated the word “patriarchy” to encompass the unjust male dominated social system that oppresses women on a societal and global level. This term is still used today to label both micro and macro forms of sexism and gender oriented violence. Essentially, liberal feminism is the belief that all citizens of all genders are created equal, and that any value attached in either gender is socially constructed. As Tong (2008) outlines in her book Feminist Thought: A More Comprehensive Introduction, liberal feminism aims at achieving gender equality by promoting equal value and complete autonomy to all genders (pg.11). Feminist theorist have deconstructed and analyzed the factors that go into the patriarchy and what perpetuates it, with violence being the central element behind male dominance. Liberal feminist theory emphasizes that men’s violence against women is one of the main tools used to oppress women and Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 16 continue the power dynamics of the patriarchy. As a result, no forms of violence are ever encouraged in liberal feminism as it is seen as promoting the very act that has oppressed women for all of recorded history. This is where liberal feminism goes against the grain with roller derby; roller derby uses physical contact and violent aggression in order to not just exert power but to subdue it in the other players. According to feminist theory, the roller derby subculture takes the very same oppressive forces that have demeaned and marginalized women and made it into a sport. Some might argue that controlling and deconstructing tools of oppression are ways of finding personal empowerment. Even though there are those who put roller derby on the same spectrum of “sport” as female mud wrestling, some claim that having a sport completely dominated by women (no matter how violent it is) is what’s needed for allfemale sports to be taken seriously in the first place. In her research, Beaver (2012) argues that the DIY ethic of roller derby created a sport only women can control, creating a collective bond with everyone participating in the sport. Beaver points out that instead of disenfranchising women, roller derby gives all power to women, which allows them to not only take the sport seriously but have others take them seriously as well. Instead of singling out women-only sports as strictly feminine (synchronized swimming being one of them), roller derby attempts to put rough edges in a sport only played by women, defeminizing it. Its through this type of discourse that violence expressed in roller derby is played off to be women taking back the power that was originally taken from them through the patriarchy. While liberal feminism completely supports the idea of womenonly sports to be taken seriously, violence should not be used in order to make that happen. Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 17 Other sports with all women leagues have the potential to give women the opportunity to feel empowered, without having to incorporate violence into the game. From tennis, to soccer, to the WNBA, women can use sports in order to gain equality without the excessive use of violence seen in Roller Derby. The problem with Roller Derby is not the sport itself; it’s the justification of the violence in it. Feminist theorists have come to the conclusion that all social constructions of value can be traced back to socialization (Tong, 2008). This means that we pick up cues on what norms, values, and behaviors are appropriate from interacting with other people, whether it is your friends, family, or classmates. This is important when considering the violent behavior expressed in roller derby players: if women exhibit violent and aggressive behavior, it has the consequence of further socializing both men and women into believing that violence is ok. Many other societal factors have lead Americans to be desensitized, and even entertained, by violence but men have overwhelming been the perpetuators of this violence. If a sport affiliated with all women players is played in a violent setting, it can fuel the flames of violence and abuse those feminist activists and theorists have worked so hard to prevent. Radical Feminism One of the main ideas behind Radical Feminism is the notion that not only do women need to have equality with men (which is a central idea of liberal feminism) but they also seek complete liberation for all women from male violence. With Radical feminism comes the idea that gender roles of both men and women should be valued and seen in the same positive light. While liberal feminism seeks to gain equality and equal treatment no matter the gender, radical feminists seek to deconstruct how we value Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 18 feminine and masculine roles that are expected of us to be of equal value. Instead of the male breadwinner seen as more important than the stay-at-home mom, radical feminists aim to have every one see both roles as equally valuable. Radical feminist theory claims that female gender roles have been devalued not only by the belief that women are the inferior sex but also by the belief that who ever has the most power has the most valuable position. The number one way to exert power and keep that power is through violence, which as a result has lead to a polarization of men and women power dynamics in almost every society found on Earth. For an example of how stigmatized violence is to Radical feminism, one can look at their views of pornography. Radical feminists believe that all forms of pornography encourage male violence and domination over men and thus feel that it should be banned in order to gain equality for women. If this is how radical feminists view pornography, one can imagine the objection of violence in a sport. In radical feminism, one of the main goals is to free women from the oppressive power and violence exerted by men, so when violence is expressed by women towards other women, it is seen as taking two steps back away from the goal. Riot Grrrl Feminism Though mainstream forms of feminism oppose any and all forms of violence, Riot Grrrl feminism has violent origins and connotations. Riot Grrrl is the feminist ideology that mirrors the Roller Derby subculture the most, so it is important to understand how Riot Grrrl feminism views violence. Riot Grrrl feminism has its origins in Punk culture (which has pre-existing violent connotations already) and evolved as a feminist culture where women have a forum to express themselves and be heard. This expression was Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 19 seen through the creation of various Riot Grrrl zines through out the 1990’s as well as a rise in girl led punk groups like Bikini Kill and Siouxsie and the Banshees. The term “Riot Grrrl” was first coined by Jen Smith, a musician and active feminist. She reacted to the violence after experiencing a neighborhood riot in Washington DC where she exclaimed, “This summer's going to be a girl riot”(Anderson, 2003, pg. 308). Instead of opposing the violence expressed in riots, she encouraged it and tacked feminism onto it. As mentioned before, both roller derby and punk culture subscribe to Riot Grrrl feminism and their ideologies. Examining women in the punk culture should further explain how women in the roller derby culture view violence. In Leblanc’s (1999) book Pretty in Punk, she explains how the masculinization of punk through out the late 70’s and 80’s led to female punks to go through the same transformation. Both male and female punks were faced with a culture of hyper masculinity when violence was seen as opposing mainstream culture and creating an environment of deviance (which they sought). This why you see female as well as male punks in mosh pits and engaging in violent aggressive discourse, examples of this are seen through recorded sayings such as “I bet a steel-capped boot could shut you up” and “I’ll slap on my lipstick and kick your ass” (Leblanc, 1999, pg.103). Roller Derby expresses this same ethic, except it never went through a transition of masculinity such as Punk. In fact, Roller Derby went through a transition of Femininity as it evolved to become completely dominated by women. This had the consequence of making the violence expressed in Roller Derby a strictly female behavior, not the result of masculinization. Roller Derby’s history of violence can be justified through Riot Grrrl ideology attached to the Punk subculture. Both this and the rules that govern the game create the Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 20 illusion that violence is another expression that women can and will project because they have the autonomy to do so. While all forms of feminism value and strive for autonomy, the expression of violence as an excuse to express autonomy is counteractive to the feminist movement as a whole. Yes, women should feel they have the freedom to express themselves however they want, but violent behavior is not an appropriate form of expression not matter what gender you are or how disenfranchised you have been. Methods: The primary data site was The Hangar at the Oaks Amusement Park, roughly 6 miles south of Portland’s city center. The Hangar is a roller rink located inside the amusement park and is where practices and events are held. For bigger events and season openers/closers, the Memorial Coliseum is used. The Memorial Coliseum, however, is not considered a data site for my research because there were no bouts played there during my observation and thus no observations were made in that location. Secondary data sites were various bars in South East Portland and Milwaukee. Some, not all, players would meet after games at these bars, but it should be noted that less than half of the players I observed attended a bar after a game. My Relationship with the setting was in the perspective of the Martian. I already had no knowledge of the subculture prior to the start of my ethnographic research, so playing this role proved to be not only easy but also beneficial. My Martian perspective of the subculture allowed the derby players to feel they needed to explain in length different aspects of their subculture/game. This provided me with useful information without having to guide the conversation too much or ask too many questions. Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 21 I am a 23-year-old white woman. The members of the Roller Derby subculture vary between 23-42 year old white women. This an estimate based on the team I was observing not every woman in the league as a whole. My own personal ascriptive features allowed the members of the team to be comfortable with me both as a woman and a white person from a middle class background. It should be noted that I come from a lower socioeconomic background than most of the members and thus made it difficult to understand or justify the amount of money spent to keep up the hobby of Roller Derby (i.e. when a member would pay $300 for a pair of skates, an amount I spend in a month). The settings are fairly safe as long as I keep my distance away from the rink railing. The bouts are held in public places run by professionals and in following all state safety regulations (i.e. fire escapes, persons capacities, etc.). There is a seating area for audience members that sit right next to the railing of the rink. No persons under 18 are allowed to sit there as it is extremely close to where players often ram each other against the rail. Sitting there has the possibility of causing injury; I personally never sat there though. My contact is the girlfriend of a male acquaintance of mine. She picked up roller derby in January 2012 as a result of a bad break up and “awesome skates that were collecting dust,” as she would put it. Both her and the members of the team I was observing will remain anonymous as my research may use data on their personal life and conversations they had with me to undermine a subculture they not only participate in but also admire. In my ethnographic research I am a known observer to my subjects (the roller derby players). Data is logged either by on-field note taking or guided conversation with Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 22 key points logged down at a later time. When observing practices and audience members during a bout (game), note taking is used in real time. In guided conversations I save my note taking for a later time to keep the conversation casual, letting the subject feel relaxed when speaking to me. This was used especially during conversations in the bar where intoxication would have the derby girls call me out whenever I brought my notebook out. Snowball sampling was used with the sample made up of the a specific team I was observing. Just like the subjects, the team too will remain anonymous for the sack of this research. There were 19 members (all women) in the team I observed, but not all of them were present at one time at the various practices and meets. At most, I observed roughly 15 of them at one time during a practice or at a game. Findings Snowball sampling was used as it encompasses the number of players observed in the Roller Derby team I focused my research on. In my study n=44, 19 players total per team (two separate teams observed, with a focus on one), 2 coaches, and 4 umpires that were present in 2 separate bouts/games. For my research I chose to focus on meanings, encounters, organizations, and lifestyles as my thinking units. Meanings can be found in the uniform and gear used in the bouts and practices: it’s important to not only get the proper protection (which shows concern on behalf of the other players for safety) but also the right protective gear from the right store. The Derby players claim there are certain protective gear made for roller derby and specifically for women, so its strongly suggested you get that specific kind of Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 23 gear. Encounters of those outside the Roller Derby culture can be seen the most when boyfriends (sometimes girlfriends), husbands/partners, family, and friends come to see the Derby bouts. The Roller Derby culture has a strong relationship with public institutions through donating and fundraising for various organizations. This includes the Sunshine division (an organization that provides emergency food and clothing relief to Portland families and individuals in need), the Special Olympics, Big Brothers Big Sisters, The Boys and Girls Club, and more. Through the donations they offer to these organizations, the Roller Derby subculture has a strong relationship with the community of Portland rather than seen as a deviant subculture. More research needs to be done on the lifestyles of these women, but one observation I made that stood out was that many of the women in the Derby team came from affluent backgrounds and had a disposable income that would suggest they are of upper middle class or higher. I make this claim based on the fact that the players pay for expensive gear and equipment out of pocket and come from rich or suburban neighborhoods like Lake Oswego and the West Hills. The DIY ethics of the Roller Derby culture has lead some researchers to believe that the control women have in the sport creates a strong bond between all the members of the culture, not just the members of the same team. In Beaver’s (2012) ethnographic study on Roller Derby girls, she pointed out that “doing it themselves ensures that skaters maintain control over their athletic activity, their organizations, and the sport as a whole” (pg.5). This mirrors the Riot Grrrl feminist subculture that is also popular here in Portland and draws many similar ideas, especially in terms of DIY mentality and creating a voice for women in a male dominate society (seen in the organization of an allfemale sport run completely by women). With this in mind, its safe to assume that Roller Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 24 Derby culture falls under the spectrum of Riot Grrrl femininity. However, it should be noted that there are those who participate in Roller Derby that don’t subscribe to the Riot Grrrl culture. In fact, as outlined in Beaver’s research, there are even members of the subculture that don’t identify as feminist at all and participate as a hobby, for fun, or as a professional athlete. To put in perspective where Roller Derby falls in the umbrella culture of feminism and sports culture, refer to the following diagram: Analysis There were hardly any situational factors that were deemed illegal or dangerous. The only form of illegal activity that I have observed was underage drinking (only one instance, and that member kept it hidden from the other players of the team). The Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 25 behavior would have been expressed if I had not been there; in fact, I believe my presence lessened the amount of illegal activity (in this case underage drinking). Misrepresentation is the sole reason why I choose to keep both the players and their teams anonymous. My motives are to deconstruct the ideologies behind the violent behavior expressed in a game of roller derby; a motive I believe the players would not appreciate. In order to appear genuine (so they feel comfortable speaking to me) I told my subjects my research highlights positive ideologies of feminism found in the Roller Derby Culture. Some levels of the Hawthorne effect may have happened as a result. For example, there were more conversations about feminism than I believe would happen if I were not present. Confidentiality is used in order to disrespect the members’ participation in the culture. All subjects and environments have been safe and took place in a public arena. Anonymity is used for all the subjects and their teams as well as certain meeting places and secondary data sites. Certain Consequences may occur as a result of the publication of this research. The Roller Derby culture donates a lot of money and entertainment resources for local charities. Highlighting the hypocrisy of their violent subculture may have charities withdraw their endorsement or affiliations. This research is a critique of the violent nature of the roller derby subculture, which its members might not appreciate hearing or reading about. The Proto-theory I originally had for my ethnographic research was to reveal not only how but also WHY the members of this subculture justify the excessive use of violence in their sport. I hoped to gain a better understanding of how the members of this Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 26 subculture express violence outside the arena, how others view their violence, and how the members themselves view the violence they perpetuate and experience themselves. For those who identify as feminist, I wanted to reveal how their expression of violence and aggression align with their own feminist ideologies. For those who didn’t identify as feminist, I want to understand what factors of the Roller Derby culture appealed to them that made them want to join. Upon extensive observation and conversation with the members of this subculture, I found that many of the women had askewed perspectives of what feminism is and what it meant to them what a feminist was. As Sally (name changed) remarked with my conversation with her: “I joined Roller Derby because every since I was a little girl I was good at kicking ass (laughter). I wasn’t good at anything else! Swear to god! I though maybe I was a tomboy but I still liked wearing dresses, remember those butterfly clips that were popular in the 90s? Yeah, I wore like 10 of them in my hair at once. Super girly. But I liked being rough and playing with the boys. I wish I had something like Roller Derby as a child, because it wasn’t until I was 20 and I joined that I realized that I still a woman, even if I like beating people up, or getting beat up myself (laughter, points to her bruises and scrapes on her arms). “ Sally’s conversation brought up a problem with feminism in roller derby: that autonomy means expressing even the most extreme spectrums of emotion, which includes violence. As mentioned before in the literature review, this is problematic Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 27 because violence is the very expression of power that feminist theorists have worked so hard to eliminate. Views of what autonomy truly is along with experiments in gender identity construction have lead to a justification of violence in the members of the Roller Derby subculture. Another member, Vanessa (name changed) mentioned something that was meant to be empowering but struck a cord when I heard it: “At least my bruises are from the games, and not from an abusive husband”. This single statement accurately sums up the ideology behind most of the members of this subculture have: that the violence in their life is controlled and not a result of abuse but of autonomy. A new theory I developed while observing this subculture is that roller derby is a product of the commodification of feminism. Also, Roller Derby teams, especially the one I am observing, is made up entirely of white women ranging form 23-42 from upper middle class or higher backgrounds. I believe roller derby not only is a commodification of feminism, it also perpetuates the lack of intersectionality in feminism, seen in the lack of minorities and those of lower socioeconomic status. Whitlock (2013) mentions in her research on Roller Derby teams in Florida that “the modern flat track roller derby employs third wave feminist rhetoric to produce and commodify the roller derby player identity” (pg. 8). She goes on to explain that feminist ideologies and commitment to the community through charities has morphed the Roller Derby subculture into a commodity of feminism itself, justified through the fact that they are “giving back to the community” but completely ignore the lack of intersectionality in their subculture. Through my own research, I have begun to see the same connections that Whitlock made. This is especially seen in the personal finance that goes into keeping up with the subculture. While on a team, a member needs to buy and replace all gear herself out of pocket. The store that Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 28 specializes in Roller Derby gear, a store located in North Portland, sell specialized gear a skates with price tags like $72 for knee pads, $300 for new skates, and $50 gloves. Limitations of Research Internal validity can honestly be hard to argue because of the small sample size, the limited amount of time that was allotted for the research, and observations of the Hawthorne affect mentioned before. The period of time I observed the teams did not give way for subject maturation; there were no visbable cues of the subjects changing through out the time I observed them, only observations on the topics they chose to talk about while in my presence (again, results of the Hawthorne affect). I believe the subjects were honest with me when expressing their opinions but were not honest in the environment and the way they expressed those opinions. Feminism was a hot topic in many conversations with the team members even though there were members that admitted to never reading any feminist literature. Focused conversation on feminism also steered away the topic of violence, which was key to my proto-theory and figuring out the justification of it. However, the combination of my misrepresentation (that I was researching feminism) and the already desensitized perspective these women had of violence (through the normalization of it through practices) created a somewhat vague image of how and why the violent level of the game is never questioned in by the members. There is a level of external validity that can be applied as a result of this research when analyzing the various demographics of the city of Portland but not the United States as a whole. Both Roller Derby and Riot Grrrl feminism is popular and has some roots in the city of Portland, which is why I feel my observations of this subculture mirror the Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 29 attitudes and values of most women who live in this city. However, it should be mentioned that the members of this subculture in Portland are all white and fairly affluent. This compromises the external validity of my research because I have observed the behaviors, norms, and values of a virtually all white rich community, verses the thinking units I would observe of a Derby team from a poor neighborhood in Chicago. As a result, I feel that my research cannot be applied too every Roller Derby player in every league in the United States, but it does created a comprehensive image of the average Portland “feminist”. This study could be expanded in further research of Roller Derby teams from more ethnically and socioeconomically diverse cities. The lack of intersectionality in Portland’s Roller Derby culture makes it hard to compare their ideologies to those from different cities and racial/class background. Also, my observations were limited to the team members themselves and not the friends or family members. Further research should be done on the opinions and observations of the players close family and friends in order to understand how those close to the derby player feel about the violent that is expressed by them as well as how they feel about watching their loved ones be at the receiving end of the violence as well. One member mentioned her 4-year-old daughter but she was never present in any of her bouts. Further research should uncover the reasoning behind such instances like that as I was not able to. Conclusion Empowerment for women means complete and utter autonomy from men in all aspects of socialization. Systematic sexism in our society and power dynamics fueled by violence expressed towards women have kept women from achieving the equality they Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 30 work so hard to achieve. When violence is the sole entertainment factor of a game completely dominated by women, it undermines the feminist ethics that strive to create a safe society for women. Roller Derby may not intentionally promote violence by women or towards women, but it certainly does not send out the message that violence is inappropriate. As important it is for women to have a forum to comfortably express who they are and what it is to be a woman, introducing violence into that forum discredits the very values that feminism stands on. It is impossible to promote gender equality through expressed violence, and maybe the Roller Derby subculture should take note. If the sport continues to play in arenas nation wide, its members should consider how their violence negatively reconstructs what it means to be a feminist. Sources Cited Rasmussen, C. (1999, February 21). The Man Who Got Roller Derby Rolling Along. Los Angeles Times, Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1999/feb/21/local/me10190 Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 31 Mabe, C. (2008). Roller Derby: The History of and All-Girl Revival of the Greatest Sport on Wheels. Seattle: Speck Press Brick, M. (2008, December 17). The Dude of Roller Derby and His Vision. New York Times, Retrieved from http:/nytimes.com/2008/12/18/sports/othersports/18devildan.html?_r=3&pagewan ted=all& McDonald, M. G. (1999). Unnecessary roughness: Gender and racial politics in domestic violence media events. Sociology of Sport Journal, 16, 111-133. Collins, R. (2009). Violence: A micro-sociological theory. Princeton University Press. Joncheray, H., & Tlili, H. (2010). Female first division rugby: a dangerous activity?. Staps: Revue Internationale des Sciences du Sport et de l'Éducation Physique, 31(90 2010/4), 37-47. Kimmel, M. S. (2008). Guyland: The perilous world where boys become men. Harper. Peluso, N. M. (2010). High Heels and Fast Wheels: Alternative Femininities in NeoBurlesque and Flat-Track Roller Derby. Doctoral Dissertations Bruised Babes: Violence & Feminism in Roller Derby 32 Putnam Tong, R. (1998). Feminist thought: A more comprehensive introduction. Westview press Beaver, T. D. (2012). “By the skaters, for the skaters” : the DIY ethos of the roller derby revival. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 36(1), 25-49. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0193723511433862 Andersen, M., & Jenkins, M. (2003). Dance of days: two decades of punk in the nation's capital. Akashic Books. Whitlock, M. C. (2013) Selling the third wave: The commodification and consumption of the flat track roller girl. Masters Abstracts International, Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1322726060?accountid=13265. (1322726060; 201317612).