A Report of the Honors Program Workgroup

advertisement

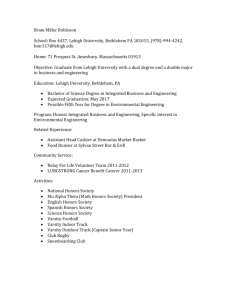

An Evaluation and Investigation of Honors Education at SUNY Oneonta and Comparable Institutions A Report of the Honors Program Workgroup February, 2014 1 Table of Contents I. Preamble: The Value of a Distinctive Honors Program ..................................................... 3 II. The Formation and Charge of the SUNY Oneonta Honors Program Workgroup .............. 3 III. A Brief History of the Honors Education at SUNY-Oneonta............................................. 4 IV. Best Practices for Honors Programs ................................................................................... 6 V. Summary of the Structure, Resource Needs, and Goals of Honors Programs at Peer Institutions........................................................................................................................... 8 SUNY Cortland Honors Program .................................................................................... 8 SUNY Geneseo Honors Program .................................................................................... 9 SUNY Fredonia Honors Program .................................................................................... 9 SUNY New Paltz Honors Program.................................................................................. 9 VI. Nationally Recognized Honors Programs ......................................................................... 10 VII. Summary ........................................................................................................................... 11 VIII. Appendices ........................................................................................................................ 12 Appendix A. SUNY Honors Programs Information Summary 2013 .......................... 12 Appendix B - Details Regarding Top National Honors Programs ................................ 14 1. University of South Carolina .....................................................................................14 2. University of Michigan ..............................................................................................14 3. U of Texas at Austin ..................................................................................................14 4. Arizona State University (Barrett Honors College) ...................................................15 2 I. Preamble: The Value of a Distinctive Honors Program “The value of Honors programs and Honors colleges for students cannot be overemphasized. For high achieving students, Honors programs and colleges offer many opportunities to make the most of their higher education. For the bright and talented students, participating in an Honors program provides the challenges necessary to stay motivated and stimulated. Honors education promotes lifelong learning through personal engagement, intellectual involvement, and a sense of community.”1 Other benefits of having a well-designed distinctive honors program include: Enhances the reputation of the institution Supports the mission and core values of the College Increases opportunities for fund-raising Increases opportunities to develop mutually beneficial relationships with public and private entities Increases the competitiveness of SUNY Oneonta students for graduate school admissions and throughout their career Increases the competitiveness of the College to continue to recruit and retain talented faculty Increases the competitiveness of the institution to continue to recruit and retain talented students Most importantly, it provides talented, motivated students with a membership in a community that provides challenging, high-impact, and engaging interdisciplinary learning opportunities and experiences II. The Formation and Charge of the SUNY Oneonta Honors Program Workgroup The SUNY Oneonta Honors Program Workgroup was formed November, 2013 by the College Senate after consultation with the College Senate Steering Committee. Members of the workgroup responded to a call made to the campus community for volunteers to join the effort to re-establish an honors program at the college. 1 National Collegiate Honors Council. The Value of Honors Programs. http://nchchonors.org/nchc-students/thevalue-of-honors-programs/ 3 Members of the SUNY Oneonta Honors Workgroup; Michael Green, Professor, Philosophy Allen Farber, Associate Professor, Art Paul Bischoff, Professor, Education William Proulx, Associate Professor, Human Ecology Elizabeth Small, Associate Professor, Foreign Languages Lesley Bidwell, Director of Networking and Telecommunications Services Rose Piacente, Admissions Karen Munson, College Advancement Selina Policar, Undergraduate Student, Communications Nick Moore, Undergraduate Student, Business The workgroup was charged by the College Senate Steering Committee with the following: 1. Briefly research the history of honors programs at SUNY Oneonta to determine how they were structured, what was successful, and what may have led to their decline. 2. Identify a variety of models of best practices in honors programs. 3. Examine the structure, resource needs, and goals of honors programs at institutions with academic missions similar to Oneonta. A date of February 24, 2014 was set for the workgroup to present its findings to the College Senate. III. A Brief History of the Honors Education at SUNY-Oneonta According to Carey W. Brush, In Honor and Good Faith: Completing the First Century, 1965-1990, p. 373: The SUCO honors program faced many difficulties in the eighties as budget and staffing reductions cut into the core academic programs. When Alan Schramm resigned as director in the early eighties, Pat Gourlay of the English Department succeeded him. One of her main tasks was to make the program more cohesive. To this end, she developed a Colloquium in Renaissance Studies for the Spring 1984 semester. In subsequent semesters, there were similar programs. Faculty members usually contributed their time as an overload. The main part of the program was still additional work in specified courses. After two or three years, Gourlay stepped down, and Allen Farber of the Art Department succeeded her. The combined efforts of Gourlay and Farber resulted in strengthening the honors program so that by 4 1987 it had an eighteen-credit core, consisting of three credits each in an Honors Literature and Composition course, Honors Thesis Research, and Honors Thesis Writing, plus nine additional credits from a total of three Interdisciplinary Colloquia. A Catalog note said that recent Colloquia titles had been “Medieval Mentalities,” “The Golden Age in Greece,” “European Civilization in the Era of WWI,” and “Romantic Revolution.” Successful completion of the honors program was noted on the student's transcript. Despite its problems in developing a cohesive honors program, Oneonta was one of only five SUNY Arts and Science Colleges to have a program. It differed also from others by being open to all students and by the contract arrangement to receive honors credit for additional work in regular courses. Dr. Allen Farber followed Pat Gourlay as Director of the Honors Program and worked to build an honors program around a core of interdisciplinary colloquia. Under the direction of Pat Gourlay, the honors colloquia started as one-semester hour additions to existing classes. The first class was dedicated to Greek culture and drew students from existing, regularly taught literature, history, philosophy, and art history classes. The colloquium met once every other week in the evening. Honors faculty would participate in working lunches each week in preparation for the next week's seminar, and many felt these were some of the most rewarding experiences they had as a faculty member. The success of these first classes led to the development of stand-alone three-semester hour evening classes. Colloquia included topics such as The Impact of Darwin's Theory of Evolution, The Scientific Revolution, the French Revolution, and the World of Late Antiquity, and included faculty from as many relevant departments as possible. These honors classes attracted faculty and students from a variety of different disciplines and helped define a community dedicated to the enhanced academic experiences provided by an honors program. One of the goals of the SUNY Oneonta Honors Program was to give honors students a sense of connection and identity with other similarly academically motivated students. Faculty involved with the honors program valued the experience because it connected them with students and colleagues from a variety of departments, thereby breaking down the insularity of the traditional departmental structures. After a couple of years of teaching the stand-alone seminars, the Honors Degree Program was created with an 18-semester hour requirement that included participation in the honors seminars and the writing of an honors thesis. The strength and weakness of the program was directly connected to the willingness of faculty to participate. While Provost Carey Brush granted a course release to the Director and the faculty member responsible for coordinating the individual seminar, the remaining faculty participated on a volunteer basis. Attempts to have departments commit resources to the program were largely futile. The 18-credit honors program lasted four years, but the lack of institutional support made the program unsustainable. In the mid-late 1990s, Virginia Harder was the director of the Honors program. Each student in the program went through the program independently. Dr. Harder had to negotiate a set of independent studies for each student. An independent study could mean taking a regularly scheduled course with enriched content, such as a research project. The difficulty in making these arrangements had the result that very few students, in some years only one and in others none, completed the program. 5 The current 30-credit honors program at SUNY Oneonta was launched in the early 2000s. Around 1999, Dr. Larkin asked the Committee on Instruction, of which Dr. William O’Dea was Chair, to devise a new Honors program. The Committee on Instruction created the current 30-credit Honors program in which students take six honors versions of general education courses (18 credit hours) in their freshman and sophomore years. In their junior year, they take one team-taught interdisciplinary course each semester (6 credit hours), and the senior year they take a six-credit hour seminar that meets during the fall and spring semesters. As part of the seminar, each student would complete and present a research project or, for students in the arts, the equivalent under the direction of a faculty mentor. The resources available to the Honors program consisted of a Director and an Honors Program Advisory Committee. There were a very limited number of honors courses available to students, and most students in the program chose to leave the program. IV. Best Practices for Honors Programs The National Collegiate Honors Council (NCHC) has identified the following as best practices of fully developed honors programs.2 1. The honors program offers carefully designed educational experiences that meet the needs and abilities of the undergraduate students it serves. A clearly articulated set of admission criteria (e.g., GPA, SAT score, a written essay, satisfactory progress, etc.) identifies the targeted student population served by the honors program. The program clearly specifies the requirements needed for retention and satisfactory completion. 2. The program has a clear mandate from the institution’s administration in the form of a mission statement or charter document that includes the objectives and responsibilities of honors and defines the place of honors in the administrative and academic structure of the institution. The statement ensures the permanence and stability of honors by guaranteeing that adequate infrastructure resources, including an appropriate budget as well as appropriate faculty, staff, and administrative support when necessary, are allocated to honors so that the program avoids dependence on the good will and energy of particular faculty members or administrators for survival. In other words, the program is fully institutionalized (like comparable units on campus) so that it can build a lasting tradition of excellence. 3. The honors director reports to the chief academic officer of the institution. 4. The honors curriculum, established in harmony with the mission statement, meets the needs of the students in the program and features special courses, seminars, colloquia, 2 Basic Characteristics of Fully Developed Honors Programs. National Collegiate Honors Council. http://nchchonors.org/faculty-directors/basic-characteristics-of-a-fully-developed-honors-program/ 6 experiential learning opportunities, undergraduate research opportunities, or other independent-study options. 5. The program requirements constitute a substantial portion of the participants’ undergraduate work, typically 20% to 25% of the total course work and certainly no less than 15%. 6. The curriculum of the program is designed so that honors requirements can, when appropriate, also satisfy general education requirements, major or disciplinary requirements, and pre-professional or professional training requirements. 7. The program provides a locus of visible and highly reputed standards and models of excellence for students and faculty across the campus. 8. The criteria for selection of honors faculty include exceptional teaching skills, the ability to provide intellectual leadership and mentoring for able students, and support for the mission of honors education. 9. The program is located in suitable, preferably prominent, quarters on campus that provide both access for the students and a focal point for honors activity. Those accommodations include space for honors administrative, faculty, and support staff functions as appropriate. They may include space for an honors lounge, library, reading rooms, and computer facilities. If the honors program has a significant residential component, the honors housing and residential life functions are designed to meet the academic and social needs of honors students. 10. The program has a standing committee or council of faculty members that works with the director or other administrative officer and is involved in honors curriculum, governance, policy, development, and evaluation deliberations. The composition of that group represents the colleges and/or departments served by the program and also elicits support for the program from across the campus. 11. Honors students are assured a voice in the governance and direction of the honors program. This can be achieved through a student committee that conducts its business with as much autonomy as possible but works in collaboration with the administration and faculty to maintain excellence in the program. Honors students are included in governance, serving on the advisory/policy committee as well as constituting the group that governs the student association. 12. Honors students receive honors-related academic advising from qualified faculty and/or staff. 13. The program serves as a laboratory within which faculty feel welcome to experiment with new subjects, approaches, and pedagogies. When proven successful, such efforts in curriculum and pedagogical development can serve as prototypes for initiatives that can become institutionalized across the campus. 7 14. The program engages in continuous assessment and evaluation and is open to the need for change in order to maintain its distinctive position of offering exceptional and enhanced educational opportunities to honors students. 15. The program emphasizes active learning and participatory education by offering opportunities for students to participate in regional and national conferences, Honors Semesters, international programs, community service, internships, undergraduate research, and other types of experiential education. 16. When appropriate, two-year and four-year programs have articulation agreements by which honors graduates from two-year programs who meet previously agreed-upon requirements are accepted into four-year honors programs. 17. The program provides priority enrollment for active honors students in recognition of scheduling difficulties caused by the need to satisfy both honors and major program(s) requirements. V. Summary of the Structure, Resource Needs, and Goals of Honors Programs at Peer Institutions To fulfill its charge the SUNY Oneonta Honors Program Workgroup reviewed honors programs at peer institutions. SUNY System Administration compiled a summary of Honors programs at 25 SUNY campuses (Appendix A). Nine of the programs listed in the summary are University Colleges. Four are reviewed below. SUNY Cortland Honors Program http://www2.cortland.edu/academics/undergraduate/honors/index.dot According to their website: “The SUNY Cortland Honors Program provides students who have demonstrated academic excellence with the opportunity for continued intellectual challenge in a rigorous, coherent and integrative program,” and “The program provides a mechanism for students to distinguish themselves and also enhances the general learning environment for all students and faculty, the College and the community.” Students must maintain a 3.2 average. The program requires 24 credit hours in a variety of honors level courses (seminar classes reserved for honors students, contract courses, specially designated writing intensive courses) Students complete a thesis in their major. 8 SUNY Geneseo Honors Program http://www.geneseo.edu/edgarfellows Some departments allow students to write Honors theses, but the college-wide program is the Edgar Fellows Program. According to their website, “the Edgar Fellows Program is designed to enhance the academic experience of a small number of especially dedicated and accomplished students through specially designed seminar courses, research opportunities, close work with program advisors, and co-curricular activities,” and “in the spirit of its founder, the Program values and fosters critical inquiry and the lively interchange of ideas between and among students and faculty.” Students must maintain a 3.4 average. First year students will complete HONR 101 & 202, then completing at least one course each year until all five core courses are completed (8 total courses are offered, not including the capstone experience). Students must maintain at least a 3.0 average each semester. Seniors must complete a capstone experience: thesis paper, presentation and Capstone Seminar. This experience is done over the course of 2 semesters. SUNY Fredonia Honors Program http://www.fredonia.edu/Honors/ The Fredonia Honors Program website emphasizes challenging and supporting student learning, and participation in unique opportunities in and out of the classroom. The learning objectives for the program include to “explore multiple disciplinary approaches to problem solving.” Students take one honors seminar class per semester for two years (total of four seminars). Most students will complete these between freshman and junior years. Seniors “can also complete a thesis within the Honors Program if they so choose.” SUNY New Paltz Honors Program http://www.newpaltz.edu/honors/ According to their website, “The mission of the SUNY New Paltz Honors Program is to provide an enhanced intellectual experience in a climate conducive to interaction among highly motivated students and faculty. This experience will seek to develop and intensify skills from a conceptual point of view in a diverse multidisciplinary analytical environment that nurtures independent thinking, creativity, respect and social responsibility.” Students must take a minimum of four seminar classes over their four years All seminars, with the exception of one, fulfill General Education requirements and are upper divisional classes. 9 VI. Students must complete forty hours of community service prior to graduation. All students must complete a senior thesis or project , to be presented at a public forum. Nationally Recognized Honors Programs Below are some honors programs that have been recognized nationally for their excellence; further details of selected institutions appear in Appendix B. Though these institutions differ from SUNY Oneonta in their size and mission, there may be some benefit from studying these successful programs. The first list below shows the programs that scored the highest when the following criteria were used to evaluate overall excellence: honors curriculum; prestigious undergraduate and postgraduate scholarships of the university as a whole; honors retention and graduation rates; honors housing; study-abroad programs; and priority registration. Large programs with more than 1,700 honors students also received bonus points for strong performance in curriculum, scholarships, and retention and graduation rates. Retention and graduation rates were estimated when no data was received from universities. The criteria for Overall Excellence are as follows: a) Honors curriculum as an estimated percentage of the graduation requirement=35%; b) Honors graduation rates, actual or estimated, 6-yr, freshman entrants only=20%; c) A metric for honors residence halls that emphasizes location and room styles=10%; d) Study-abroad programs for the university as a whole or for honors only=7.5%; e) The availability of priority registration for honors students=2.5%. See more at: http://publicuniversityhonors.com/methodology/#sthash.pN5uR5JV.dpuf The leading public university honors programs in OVERALL EXCELLENCE are the following: 1. University of Michigan 2. University of Virginia 3. UT Austin 4. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 5. Arizona State University This next list shows programs according to their HONORS FACTORS only, meaning that the university-wide data for prestigious scholarships are not included: 1. University of South Carolina 2. University of Michigan 3. UT Austin 4. Arizona State University 5. University of Georgia 10 See more at: http://publicuniversityhonors.com/2012/03/23/tophonors/programs/#sthash.qSCiL Ubg.dpuf VII. Summary The following represents the findings of the SUNY Oneonta Honors Program Workgroup: A well-designed distinctive Honors program that incorporates best practice confers numerous tangible benefits to students, faculty, and the institution The National Collegiate Honors Council has identified the best practices of fully developed Honors programs The success and sustainability of Honors programs requires the full support of administration, academic departments, and faculty SUNY and Private Peer institutions have established Honors programs Item 6 on the NCHC list of best practices emphasizes that “The curriculum of the program is designed so that honors requirements can, when appropriate, also satisfy general education requirements, major or disciplinary requirements, and pre-professional or professional training requirements.” The essence of item 6 is that all talented, motivated students who meet the criteria to participate an honors program should be able to do so regardless of their major. However, students in highly-structured programs often find it difficult, if not impossible to integrate any honors coursework into their curriculum that doesn’t apply directly towards their program-specific graduation requirements. Consequently, the participation and contribution of academic departments in an institution’s honor program is essential for providing talented, motivated students in highly structured majors the opportunity to participate in a structured honors experience and join the honors community at the institution. The members of the Honors Program Workgroup look forward to contributing to the ongoing discussion of the future of Honors education at SUNY Oneonta. 11 VIII. Appendices Honors enrollment SAT combined ACT composite H.S. GPA Scholarshi ps Contact 12,875 125 450 1330 30 95-99 Y Jeffrey Haugaard 518.442.9067 Binghamton University at Buffalo 12,356 100 215 1400-1580 32-35 96-99 Y Y William 607.777.3583 19,506 325 1,060 1320-1420 29-33 95-99 Krista Ziegler Hanypsia k Stony Brook University Colleges 16,003 462 1,569 1350-1470 30-33 94-99 Ryan Donelly 631.632.6867 Brockport 7,133 90 451 1240-1300 27-29 94-97 Y Donna Kowal 585.395.5400 Cortland 6,300 32 165 1200-1300 26-28 92-98 N Lisi Krall 607.753.4827 Fredonia 5,232 105 260 1190-1300 26-30 93-96 Y David Kinkela 716.673.3876 Geneseo 4,950 40 160 1390-1460 29-36 95-99 Y Olympia Nicodemi 585.245.5390 New Paltz Old Westbury 6,685 30 150 1280 28 95 N Patricia Sullivan 845.257.3456 4,413 40 135 1100-1200 24-27 90-95 Y Anthony DeLuca 516.876.3177 Oswego 7,300 80 225 1200-1300 26-29 93-96 Y Robert 315.312.2190 Plattsburgh 5,706 90 375 1200-1280 25-28 92-96 Y James Moore Armstron g Potsdam Colleges of Technology 3,952 70 324 -- -- 95-98 Y Thomas Baker 315.267.2900 Alfred State 3,528 10 30 1030-1160 22-25 86-92 N Terry Morgan 607.587.4187 Canton 3,780 15 16 1001 24 90 Y Nicole Heldt 315.386.7401 Cobleskill 2,512 20 41 1200 -- 90 Y Mary Rooney 518.255.5562 Delhi+ Community Colleges 3,331 14 27 1075 -- 90 Y Akira Odani 607.746.4050 Broome 6,700 -- 25 -- -- 90 Y Jenae Norris 607.778.5001 Cayuga ColumbiaGreene 4,747 -- 40 -- -- 85 Y Bruce Blodgett 315.255.1743 2,078 -- -- -- -- 85 -- Michael Phippen 518.828.4181 Corning+ 5,301 -- -- -- -- -- Y Karen Brown 607.962.9151 Dutchess+ 10,495 25 50 -- -- 85 Y Werner Steger 845.431.8522 Erie 13,990 -- 100 -- -- 86-99 Y Sabrina Caine 716.851.1720 Telephone Freshman enrollment Albany Campus Undergrad enrollment Appendix A. SUNY Honors Programs Information Summary 20133 University Centers 3 Y 716.645.3020 518.564.3075 State University of New York Honors Program Information Summary. Retrieved November 25, 2013 from http://www.suny.edu/student/downloads/pdf/honors_programs.pdf 12 Appendix A. SUNY Honors Programs Information Summary 20134 (continued) FIT 10,207 46 167 1200 -- 90 Y Irene Finger Lakes FultonMontgomery 6,520 30 50 -- -- 85 Y Curtis 2,683 23 35 -- -- -- Y Julie Genesee 6,965 -- 11 -- -- -- Y Herkimer+ Hudson Valley 3,507 -- -- -- -- 88 13,750 -- -- 1200 -- Jamestown+ 5,102 40 62 -- Jefferson+ Mohawk Valley 4,057 -- -- 7,451 -- Monroe 17,296 Nassau+ 23,074 Niagara Onondaga Orange Rockland 7,036 12,038 6,716 8,179 Buchman NehringBliss 212.217.4590 518.736.3622 Tanya Mihalcik LaneMartin -- MaryJo Kelley 315.866.0300 90 Y Brian Vlieg 518.629.8135 -- 93 N Nelson Garifi 716.338.1000 -- -- -- -- Michael Avery 315.786.2444 -- -- -- -- -- Maryrose 315.792.5301 -- 554 1100 24 87 Paul 150 300 1100 23 90 Y Y Eannace D’Alessan dris Melanie Hammer 516.572.7775 Rebekah Keaton 716.614.6809 Stephanie Putnam 315.498.2490 Maynard Schmidt 845.341.4040 Cliff Garner 845.574.4715 Eileen Abrahams 518.381.1403 Albin Cofone 631.451.4778 Cindy Linden 845.434.5750 17 56 55 132 29 91 77 330 1090 1100 1200 1150 -23 -25 -90 90 90 Schenectady 6,431 20 20 -- -- 90 Suffolk 26,219 178 628 1100 24 90 Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 585.785.1367 585.345.6800 585.292.2490 Sullivan+ Tompkins Cortland 1,757 12 25 -- -- 85 3,581 -- 36 -- -- -- N Karen Pastorello 607.844.8222 Ulster Westchester + 3,702 -- -- -- -- -- -- Matthew Green 845.687.5022 13,997 -- 350 -- -- 95 Y Dwight Goodyear 914.606.6951 4 State University of New York Honors Program Information Summary. Retrieved November 25, 2013 from http://www.suny.edu/student/downloads/pdf/honors_programs.pdf 13 Appendix B - Details Regarding Top National Honors Programs 1. University of South Carolina The Honors Program requires greater depth in their majors—with honors courses in all majors—and greater breadth across the curriculum by providing a rich set of small honors seminars covering a very wide variety of topics. Graduation with a degree with Honors from the South Carolina Honors College requires 45 honors credits, including courses across the liberal arts curriculum and a culminating senior thesis or project. To encourage learning outside the classroom, the Honors College requires students to have at least three-credit hours of honors educational experience outside of the traditional classroom setting. A student will be able to satisfy this requirement through undergraduate research credit, internship credit, service learning credit, or study away credit--typically through study abroad, but this can also include National Student Exchange or the Washington Semester Program. • Maintain a cumulative Grade Point Average of 3.000 or higher • Successfully complete at least two Honors courses per academic year (fall-spring) • Successfully complete English 105i or 105 PIT Journal, if applicable • Successfully complete one Honors First Year Seminar, if applicable. The Honors First Year Seminar counts as one of the two Honors courses mentioned in #2 above. • The Honors Carolina office reviews each student's progress throughout. http://schc.sc.edu/academics-0 2. University of Michigan The Honors Program's curriculum offers a wide range of challenging courses in almost every department, with majors in every field in the College. The program offers special seminars, courses, and direct involvement with faculty from the start of students' lives at Michigan. Students are expected to elect half their course work in Honors; many do more. Many Honors students participate in research during their first two years, and almost all Honors seniors pursue their own independent research projects under the guidance of a faculty mentor, leading to an Honors senior thesis. http://www.lsa.umich.edu/honors 3. U of Texas at Austin Plan II is a carefully designed core curriculum honors major with very specific multidisciplinary course requirements and strong emphases on problem solving, critical and 14 analytical skills, and particularly on writing—including a capstone thesis requirement. The Plan II Honors core requirements include: • A year-long freshman course in world literature from the ancients to the present • Three semesters of interdisciplinary topical or thematic tutorials and seminars that develop and refine students' analytic and synthesizing capacities • A year-long philosophy course for sophomores • A semester of honors social science • Two semesters of non-US history • A four-semester honors sequence in modes of reasoning, theoretical math, or calculus, life sciences, and physical sciences • A senior thesis, a major independent research and writing project, which is the culmination of a student's academic program in Plan II http://www.utexas.edu/cola/progs/plan2/about/ 4. Arizona State University (Barrett Honors College) Incoming freshmen take The Human Event classes (HON 171 and 272/273/274) during their first and second semesters. In small, student-centered, seminar-style classes, students explore the world’s great literature and humanity’s most-profound ideas. They work closely with dedicated members of the Barrett faculty who encourage critical thinking and composition – skills that will benefit them throughout their entire academic career. Honors Courses and Honors Enrichment Contracts Students who enter Barrett as freshmen follow a program of study requiring 36 hours of honors coursework, integrated into the 120 hours of courses required of all students for graduation from ASU. While in the college, Barrett students enroll in honors seminars that are small in size – no more than 25 students per class – and taught by full-time faculty. Over 100 seminars are offered each semester, in topics as varied as “Theories of Enlightenment: Kant, Foucault, Habermas” and “Continuing Challenges in Latin America.” Other honors courses include special sections of university classes and individual enrichment contracts or group projects with professors in regular university courses. http://barretthonors.asu.edu/about/academic-experience/#sthash.HYCkZ672.dpuf 5. University of Georgia In order to remain in good standing in the Honors Program, students must maintain a cumulative GPA of 3.4 and a minimum Honors GPA of 3.3. Furthermore, students must complete Honors courses on a regular basis to show progress towards graduation with Honors. 15 The following courses are included in determining Honors course credit and GPA for good standing: • All courses identified by an “H” in the suffix and graded on an A/F basis. • All three-credit hour, A/F graded courses beginning with an “HONS” prefix. • Certain non-Honors courses found in the Honors course list (e.g., PHYS 1211) • Graduate courses at the 6000 level or higher • Approved Honors Option courses All Honors course grades, regardless of category, are included in the Honors GPA, with the exception that three one-credit hour pass/fail Honors courses may equal one regular Honors course, but do not affect the Honors GPA. http://honors.uga.edu/ 16