mec12583-sup-0001-TableS1-FigS1

1 Supporting Information

2 Movements of subadult and adult female lemon sharks in Florida and The Bahamas

3 Fig. 1 provides a synthesis of tag-recapture on the long distance movements of

4 subadult and adult female lemon sharks in Florida and The Bahamas compiled from the

5 National Marine Fisheries Cooperative Tagging Program (NMFS-CTP) database, some

6 of which has already been published elsewhere. We supplemented this with unpublished

7 information on the movements of adult female lemon sharks fitted with internal acoustic

8 transmitters and remotely tracked using passive acoustic telemetry. Here, we provide

9 additional details of this ongoing study.

10 Adult lemon sharks were targeted at Jupiter, Florida, one of the few known places

11 in the region where this life-stage occurs in large, predictable aggregations. Individuals

12 were captured at ca 25-30 m depth in the winter months (January to March) from 2005 to

13

14

2009. Sharks were collected using drift lines with single baited 20/0 circle hooks. All sharks were fitted with a coded acoustic transmitter (Vemco

®

V16H) internally implanted

15 into the coelom. Nominal battery life for the tags was 84 months. Intervals for the coded

16 signals were randomized between 90 and 360 seconds. All sharks were released after the

17

18

19 hook was removed, with a typical at-vessel handling time of less than 15 minutes . Longrange movements of sharks carrying acoustic transmitters

were determined from transmitter

detection strings on underwater Vemco receivers that were deployed by us

20

21 and others. Approximately 165 Vemco acoustic receivers are deployed by the Florida

Atlantic Cooperative Tracking (FACT) research group, spanning a total of 310 km of

22

23 coastline between Delray Beach and Cape Canaveral. The Atlantic Coastal Telemetry

(ACT) array research group has approximately 1,000 monitors deployed in various

24 locations along the U.S. eastern seaboard north of the FACT array (pers. comm.

25

26

Dewayne Fox – ACT coordinator). Long distance movements were also detected through tag returns from commercial fishing operations.

27 Lemon sharks fitted with acoustic transmitters at Jupiter were detected on local

28 receivers for a few months after tagging, after which they all dispersed from the local

29 area. After correcting for two sharks known to have been killed by fishermen within a

30 year of tagging, 33 of 41 individuals (80.5%) returned to the tagging site in subsequent

31 years (Supplementary Table 1). Sharks were detected on receivers or captured by

32 fishermen hundreds of kilometers away along the U.S. coast, ranging from the Dry

33 Tortugas, Florida (dispersal distance from tagging site ~ 515 km) to the Santee River

34 Mouth, South Carolina (~ 720 km from tagging site, Fig. 1). Sharks were also detected on

35 receivers deployed in Altamaha Sound Georgia, (~ 515 km, Fig. 1) and Cape Canaveral,

36 Florida, (~ 225 km, Fig. 1). All of these movements represent minimum dispersal given

37 that the majority of the coast, especially south of Jupiter, is not under receiver

38 surveillance. The average dispersal of adult females was 299.8 km and ranged from 225

39 km to 715 km.

40

41

42

43

44

45 Supplementary Table 1. Maximum-recorded dispersal distances (km) and years of return to tagging site for adult lemon sharks fitted

46

47

48 with acoustic transmitters and acoustic transmitters off Jupiter, Florida. “Max distance recorded” is the coastal distance between the shark’s tagging location off Jupiter and either (a) a receiver it was detected on (“Acoustic detection” under “Detection type and shark fate”), (b) a location provided by a fishermen who caught the shark (“Tag return”) and either harvested the animal or released it alive

49 or (c) from the pop-off location of a pop-off satellite archival tag (PSAT). “Return years” refers to winter periods (January to April)

50 when the individual was detected by receivers off Jupiter, indicative of philopatry.

51

52

Shark ID

34

36

2140

2141

2143

2145

2146

2147

2148

2151

7949

7950

Date tagged

23-Feb-07

24-Feb-07

27-Feb-07

5-Feb-08

26-Feb-07

8-Feb-08

15-Feb-08

9-Feb-08

15-Feb-08

9-Feb-08

22-Feb-08

26-Feb-08

Total length (cm) Sex

254

255

236

M

M

M

251

245

231

237

231

232

238

248

268

M

M

M

M

F

M

M

M

M

Max distance recorded (km)

720

512

512

720

275

225

915

505

512

607

512

715

2008

Y

Y

Y

N/A

N

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Return years

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

2009

Y

Y

Y

N

N

Y

Y

N

N

Y

N

Y

2010

N/A

N/A

N/A

N

N/A

Y

2011

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N

N/A

N/A

N/A

N

N

Detection type and shark fate

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Tag return released

Acoustic detection

Tag return released

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Tag return released

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

25-Feb-08

11-Mar-08

25-Feb-08

25-Feb-08

12-Mar-08

11-Mar-08

6-Sep-08

6-Sep-08

8-Feb-12

22-Feb-09

22-Feb-09

8-Mar-09

21-Feb-09

14-Feb-09

21-Feb-09

21-Feb-09

21-Feb-09

21-Feb-09

22-Feb-09

14-Feb-09

21-Feb-09

13-Feb-09

1-Mar-10

1-Apr-10

29-Jan-10

20-Feb-10

1-Apr-10

1-Apr-10

55121

55122

55123

55124

55125

55126

55127

63424

63425

63427

63429

63430

63431

7955

7956

7959

7960

7961

7966

7967

13038

52494

52993

52994

52995

55114

55115

55116

276

279

293

255

242

260

260

264

284

245

260

237

257

240

265

280

274

247

242

240

247

229

255

242

262

235

263

257

M

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

M

F

F

F

F

F

M

F

M

M

F

F

F

F

M

M

F

M

M

225

225

225

225

500

225

225

225

518

225

225

225

715

225

225

225

505

225

225

225

96

512

225

225

225

230

340

1020

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Y

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

N

Y

Y

Y

Y

N/A

Y

Y

Y

Y

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Y

N

Y

N

Y

N/A

Y

Y

N

Y

Y

Y

Y

N

N

Y

N

Y

N

N

N

Y

N

N

Y

Y

Y

N

N

N

Y

N

Y

N/A

Y

Y

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

Acoustic detection

Sat Tag

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Tag return harvested

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Sat Tag

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Tag return harvested

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Tag return harvested

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Tag return harvested

Acoustic detection

Tag return harvested

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

53

63433 29-Jan-10

63435

63436

23-Feb-10

19-Feb-10

63437 28-Jan-10

323622 26-Feb-08

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

266

280

220

278

265

F

F

F

F

M

225

225

225

225

230

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

Y

N

Y y

N/A

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Acoustic detection

Tag return harvested

75

How many of the tagged 1993-1998 sharks are likely to have survived to adulthood?

76

77

78

To put individual detections of natal philopatry in context it is useful to have some understanding of how many of the females we tagged from 1995-1998 were probably still alive in 2008-2012 and would have matured and had their first litters before

79

80

2012. Many parameters are needed to make such an estimate. We stress that what we present is the only approximation that we can make with the available data, and it should

81 be viewed as providing a very general idea of likely number of survivors.

82

83

The probability of each tagged female surviving to have its first litter was calculated by multiplying the annual survival rates for each year from when it was last

84

85 observed until the age of first reproduction, and excluding those that would have pupped for the first time after 2012. The expected number of females to survive to pup was the

86 sum of these individual probabilities. A Monte Carlo simulation was used to estimate the

87 uncertainty in the estimate (Cortes 2002, Babcock et al. 2013). For Monte Carlo

88 simulation, each parameter (survival age 1-4, survival age 5+, age at reproduction) is

89 given a probability density function representing the uncertainty in the estimate; random

90 values of the three parameters are drawn from their probability density functions, and the

91 number of individuals that survive to pup is recalculated for each set of parameter values.

92 The 95% confidence interval of the number of survivors is calculated from the 2.5 and

93 97.5 percentiles of the distribution in estimated number of survivors.

94 The annual survival fraction from age 1-4 was drawn from a triangle distribution

95 between 0.43 and 0.85, corresponding to the range of survival values obtained during a

96 previous study of lemon sharks conducted at Bimini from 1995-2000 (DiBattista et al.

97 2007). The annual survival from age 4 and higher, after the sharks have left Bimini, was

98 drawn from a triangle distribution between 0.86 and 0.91, the same distribution used by

99 Cortes (2002), based on longevity data. The age at maturity was selected randomly with

100 equal probability from age 12, 13 and 14, so that the females would return to pup at age

101 13, 14 or 15. The smaller value is taken from previous studies (Brown and Gruber 1988);

102 the larger values reflect the fact that the females in this study made their first return at

103 later ages. For each of 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations, for each tagged shark, values of

104 survival between age 1-4, survival age 4+, and age at maturity were drawn. The survival

105 in each year, from the age when the shark was last captured (age 1 to 3) to its age at first

106 pupping were multiplied to produce a total survival probability for each shark. For some

107 individual sharks, the age at last capture was recorded as a range (e.g. 1-3), in which case

108 an age was drawn randomly with equal probability from ages 1, 2 and 3, for each of these

109 sharks in each Monte Carlo draw. The expected number of tagged females in each

110 simulation to survive to produce their first litter was the sum across all tagged sharks of

111 their survival probabilities, excluding those whose age at maturity implied that they

112 would have their first litter after 2012. The analyses were conducted in R, version 2.15.2

113 (Carnell 2011; R Core Team 2012). We enumerated juvenile females that were tagged in

114 Bimini from 1995-1998 that survived beyond the age of 2 years based on recapture

115 information (N=128). Monte Carlo simulations estimated that only 15 of these

116 individuals are likely to have survived to deliver their first litters up to 2012 (95% C.I.=

117 8-25).

118 Alternative nursery habitat

119 Lemon shark nursery habitat in the region is characterized as being shallow (< 1

120 m depth), close to shore, and occurring over sand and seagrass substrates, often near

121 mangroves (Morrissey and Gruber 1993; Gruber et al. 2001). We used the habitat-layered

122 map in The Bahamas GIS viewer (Mumby 2012) to calculate the percentage of available

123 coastline and near shore benthos with these characteristics within a 200 km radius of

124 Bimini, a conservative estimate of the dispersal range of adult female lemon sharks based

125 on compiled tagging and telemetry data above (Supplementary Table 1). Given this

126 dispersal range, GIS analysis suggests that Bimini constitutes ~ 2.4% of the nursery

127 habitat available to them, assuming that this entire potential nursery habitat is actually

128 used. As a preliminary assessment of lemon shark use of this potential nursery habitat we

129 conducted a hook-and-line survey in this habitat at two locations in Andros Island and

130 two locations in the Berry Islands from May 27-June 6, 2013. We observed large

131 numbers of juvenile lemon sharks in all four locations and captured 18 individuals < 90

132 cm TL in Andros and 11 in the Berry Islands (Supplementary Figure 1). These

133 preliminary validation efforts suggest that GIS analysis provides a useful approximation

134 of realized nursery habitat for lemon sharks within a 200 km radius of Bimini. Assuming

135

136 that the habitat we monitored at Bimini is 2.4% of the potential nursery habitat for 8-25 possible tagged returnees, then i f female sharks chose nursery areas locations randomly

137

138

139 out of the available habitat the probability that an individual female would choose the

Bimini nursery would be 0.024. The probability of six or more of the surviving 8-25

Bimini females giving birth at Bimini under the null hypothesis of randomly choosing

140

141 nursery habitat would be less than 0.0001 (calculated from the binomial distribution with probability 0.024 and sample size 8-25).

142

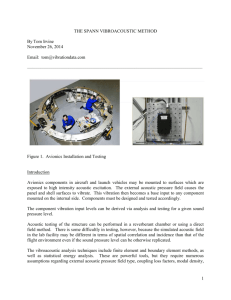

143 Supplementary Figure 1: Islands with lemon shark nursery habitat on the Great Bahama

144 Bank, Bahamas. Areas in yellow boxes on left panel are shown on the upper right (Berry

145 Islands) and lower right (Andros Island). Red boxes outline the area that was surveyed

146 for lemon sharks. Red circles show capture locations of juvenile lemon sharks (< 90 cm

147 TL) at each site (N = 11 at the Berry Islands; N= 18 at Andros). Size of circle is

148 proportional to the number of individuals captured at each site.

149

150

151

152

References

Babcock EA, Coleman R, Karnauskas M, Gibson J (in press) Length-based indicators of

153 fishery and ecosystem status: Glover’s Reef Marine Reserve, Belize. Fisheries

154

155

156

Research .

Brown CA, Gruber SH (1988) Age assessment of the lemon shark, Negaprion brevirostris , using tetracycline validated vertebral centra.

Copeia, 3 , 747-753.

157

Carnell R (2011) Triangle: Provides the standard distribution functions for the triangle

158

159

160 distribution. R package.

Cortes, E (2002) Incorporating uncertainty into demographic modeling: application to shark populations and their conservation. Conservation Biology, 16 , 1048-1062.

161

162

DiBattista JD, Feldheim KA, Gruber SH, Hendry AP (2007) When bigger is not better: selection against large size, high condition, and fast growth in juvenile lemon sharks.

163

164

165

Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 20 , 201-212.

Gruber SH, De Marignac JRC, Hoenig JM (2001) Survival of juvenile lemon sharks

( Negaprion brevirostris ) at Bimini, Bahamas, estimated by mark-depletion

166

167 experiments. Transactions of the America Fisheries Society, 130 , 376-384.

Morrissey JF, Gruber SH (1993) Home range of juvenile lemon sharks, Negaprion

168

169

170 brevirostris . Copeia, 2 , 425-434.

Mumby PJ (2012) Bahamas GIS database. http://www.marinespatialecologylab.org/resources/bahamas-gis-database/

171

172

R Core Team (2012) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R

Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria.