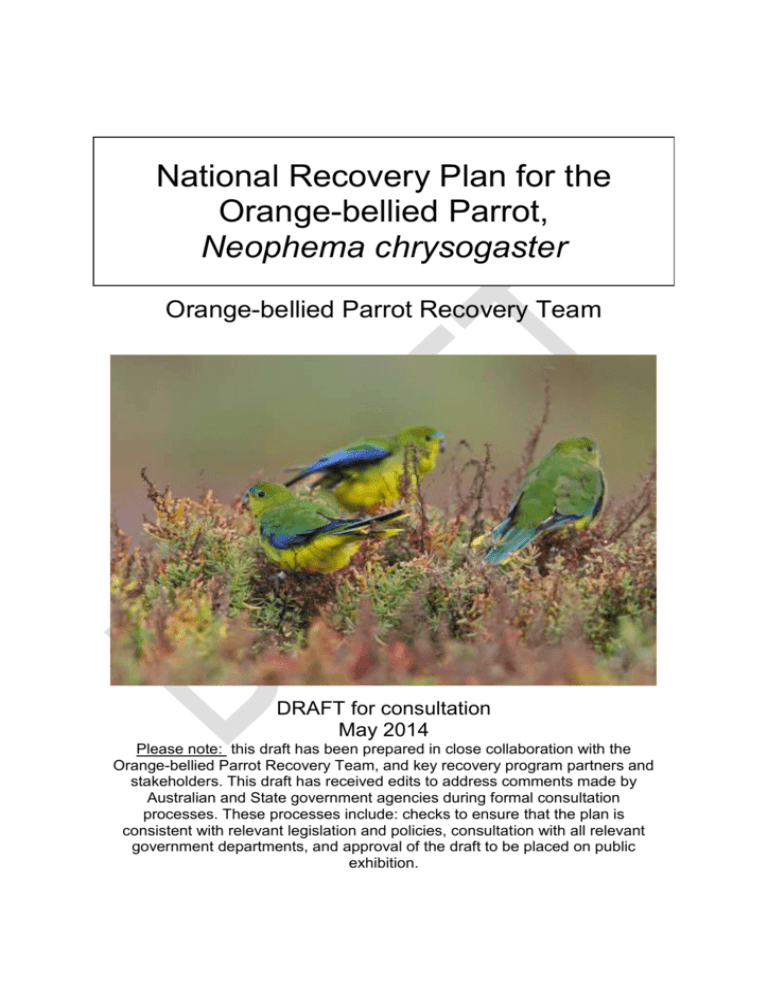

National Recovery Plan for the Orange

advertisement