Challenges of policy implementation in developing countries

Is Industrial Energy Efficiency what developing countries need?

Report from an intern supporting UNIDO in the making of the Industrial Development

Report (IDR) “If Industrial Energy Efficiency pays – Why isn’t it happening?”

1

Table of contents

Methodology ........................................................................................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

2

Internship, DIR and UNIDO

As a part of the DIR master programme the ninth semester consists of an internship with an international organisation with a development or an international relations aspect. The internship has on my part been undertaken in the Development Policy and Strategic Research Branch of the

Regional Strategies and Field Operations Division of UNIDO in Vienna with a special focus on

Industrial Energy Efficiency (IEE) in developing countries. My assignments have been research assistance for the upcoming Industrial Development Report (IDR) with the headline: “If Industrial

Energy Efficiency pays, why is it not happening?” The purpose of the IDR is to look into the evidence supporting the view that there are a variety of barriers preventing industry from adopting

Energy Efficiency technologies which are considered profitable in a number of ways. It also claims that these barriers can be overcome and describes the various policy mechanisms that can effectively address these barriers. Finally it shows how these actions have not yet been fully explored in both developed and developing countries.

My main work consisted of searching for and categorizing information on developing countries implementation and efforts towards IEE specific policies and of finding information on technological change and correlated changes in energy consumption in specific technological production processes in energy intensive industries or so-called heavy industries.

Regarding the latter, the particular industries I looked into were Petro Chemicals and Cement. In

Petro Chemicals I looked for changes within Steam cracking, Ammonia production,

Polyethylene/polypropylene production (suspension, high pressure, gas phase process) and regarding cement I looked at when changes were made regarding the development and use of

Vertical shaft kiln, Wet kiln, Dry kiln (long kiln), NSP kiln (dry kiln, precalciner, preheater) (1-2-3-

4-5-6 step pre-heater), Waste heat recovery for power generation, Clinker substitutes. In general this was a highly technical and very much out of my usual field, but to some degree it made me realize the extent to which technology transfer plays an important role for upgrading industrial processes.

The most in-depth going tasks were related to Energy Efficiency policies in developing countries.

The geographical area covered consisted of thirteen Latin American countries and three Eastern

European countries and the search was focused on 20 different policies which specifically increase the level of IEE by overcoming the identified barriers. The policies in this case were: information policies, institutional, regulatory and legal policies, financial and investment policies and technology policies. In this process I looked for which policy measure, implementation, challenges,

3

outcomes and key lessons that could be found for each of the policies in each country. However regarding most countries, the area of IEE had not yet been turned into a highly developed policy focus, so finding satisfactory information for each country was often reduced to a handful of hits which with few exemptions were found in the economies in transition or had been strongly supported by development banks or bilateral aid. A few examples showing this point are brought in

Annex 1.

My internship thereby introduced me to the area of Industrial Energy Efficiency and industrialization. At the beginning I was puzzled that a development organization like UNIDO would focus their primary annual report on something which to me at first glance only had a spurious relationship to development and the deepening and diversifying of industrialization in developing countries. However it does seem that IEE has something positive to offer especially countries with energy-intensive industries as the energy savings that can be achieved can be very substantial. However increasing energy savings are only one part of a successful industrial development process and a small one at that. Seen from a developing country perspective it increases the competitiveness of private enterprises and SME’s if energy savings are achieved successfully and in a broader perspective it leaves room for the state to transfer excess energy to other parts of society who in many cases have insufficient or unreliable energy access. Increasing energy access can have positive developmental outcomes. These are stated as “waste reduction, reduced need for future investments, freeing up of capital and hedging of fuel risks, enhanced competitiveness, and help in long term resource planning.”

1

1 SEPIR:2007:8

4

Introduction

The understanding of development today has to be understood within a number of interrelating aspects that all put the sustained inequalities of the peoples of the earth into important perspectives for how this picture can change in the future. First, inequality is today at a much higher level than it was in 1950. At that time the average Ethiopian had an income 16 times less than an average

European or American. Today the same Ethiopian earns 35 times less

2

. During the same period only few developing countries have managed to move their economies towards that of the developed countries. In the mean time the temperature of the globe has risen to dangerous heights endangering the whole of the planet and the fossil fuels that have fired both the economic growth spell of the developed countries as well as the climate changes arguably already happening, are about to peak.

Therefore a future scenario of continued development that hopefully will entail increased living standards to the vast populations of the developing countries who are yet to see sustained economic growth.

The combination of development, oil dependency and concern for the environment is although not an entirely new invention. “Our common future” was the name of the report published by the world commission on environment and development; a commission that comprised of the political, academic and economic leaders of the world. A part of the introductory statement to that report goes as follows:

(T)he “environment” is where we all live; and “development” is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable. Further, development issues must be seen as crucial by the leaders who feel that their countries have reached the plateau towards which other nations must strive. Many of the development paths of the industrialized nations are clearly unsustainable. And the great economic and political power, will have a profound effect upon the ability of all peoples to sustain human progress for generations to come”

Gro Harlem Brundtland: Oslo, 20 march 1987

3

2 UN:2006:v

3 UN:1987:14 Report of the world commission on environment and development – “Our common future”

5

Problem area

This report will take a look at the support for Industrial Energy Efficiency (IEE) as promoted by the

United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) and relate this to the criticisms against the policy of the International Development Policy Establishment (IDPE) and the Now

Developed Countries (NDC’s) made by heterodox economist Ha-Joon Chang of forcing/recommending institutions and policies that in recent history has been made common in the

NDC’s, to be adopted by developing countries.

The motivation for this perspective is that the implementation of IEE has proved inherently difficult even to OECD countries and that it, when it has succeeded, has required a substantial and concerted political and institutional effort. Describing the purpose and aim of the Organisation, UNIDO’s

Mission Statement is as follows:

“UNIDO aspires to reduce poverty through sustainable industrial development. We want every country to have the opportunity to grow a flourishing productive sector, to increase their participation in international trade and to safeguard their environment.” 4

Therefore the perspective of IEE will be analyzed in comparison with the principles of Strategic

Industrial Policy (SIP) as the main aim of the organisation focuses on industry per se and not energy. Energy, industry and economic growth are all different but mutually supportive sides of development, but the interplay between them is what this report will focus on. On the subject of

Industry this report will specifically refer to the nine principles of SIP set forth by Laurids

Lauridsen in his 2010 “Strategic Industrial Policy and latecomer development: The What, the Why and the How”. This paper rests on the knowledge and principles laid out in a number of other papers that also addresses the needs and possibilities in industrialisation strategies.

5

With this background and considering the main result from my work of looking into IEE in developing countries during my internship at UNIDO being that not many developing countries had implemented policies that were even remotely specific enough to be characterised as IEE policies, this paper will provide an investigation into the feasibility of implementing IEE in developing countries. The question that arises is whether making developing countries focus some of their policy making capacities on greening the existing industry in their country will impede other developments important to the industrialisation process?

4 http://www.unido.org/index.php?id=7851

5 Lauridsen points to (Lall, 2004, 23-24) (Mathews, 2006, 325-329) (Rodrik, 2007, 114ff) (Rodrik, 2008, 25-30)

(Haussmann et al., 2007,9-10) (Shafaeddin,2005,1148ff) (Storm and Nestepad, 2005) (Altenburg, et al., 2008, 143ff)

(Wade, 2007, 10-11) (Wade, 2006, 10-11)

6

Problem formulation

The problem formulation guiding this paper will be centered on the relevance of IEE in the debate on industrial development. As mentioned above it will be guided by (i) the view on industrialization put forth by Lauridsen (2010), (ii) The criticism by Chang, (2003) of the IDPE and (iii) the potential of IEE in developing countries as described by Mckane, Price and Rue du Can, (2007). Therefore the problem formulation is as follows:

“

To which extent do the potentials of Industrial Energy Efficiency coincide with the principles of

Strategic Industrial Policy and the implementation capacity of developing countries and in this way play a valid part of industrial development?”

The IEE aspect will be discussed with specific reference to UNIDO’s promotion of the topic drawing on the web sources of the organisation describing its approach. The potentials of UNIDOs promotion of IEE regarding sustainable industrial development will be measured against the principles of SIP as laid out by Lauridsen 2010. The main purpose here is to investigate whether

IEE supports similar goals as those of SIP and whether there are substantial conflicts of interest regarding the need for resources in implementing IEE and SIP simultaneous. An important assumption here is that developing countries have limited human resources to implement substantial policies like the SIP and IEE and hence will have to choose to either use less resources in their implementation and formulation of their industrial policy in order to e.g. use some political and bureaucratic capacity to implement and formulate policies aiming towards IEE. It is this dilemma the problem formulation aims to elaborate on. What is possible and what is not regarding government action to support both of these perspectives?

Structure

The answering of the problem formulation will be divided into three parts.

One : the positions, SIP and IEE will be presented in order to separately present two diverging positions on what is important for the development process in developing countries.

Two : here UNIDOs IEE strategy will be analysed with reference to the criticism of the IDPE made by Ha-Joon Chang and the principles of SIP. This is to be the main part of the report and will discuss the relative importance of the different aspects in the development process.

7

Three : this part will present the conclusion of the report and subsequently apply some perspectives on the findings from the analysis.

Part 1

Strategic Industrial Policy (SIP)

Laurids Lauridsens 2010 article “Strategic Industrial Policy and Latecomer Development: The

What, the Why and the How” will function as the main source on do’s and don’ts in industrialization efforts in developing countries. Lauridsen, defines industrial strategies are:

“Forward-looking packages of policies aimed at steering economic activity in a particular direction.” 6

The main objectives of industrial strategies are to create 1) industrial diversification, 2) industrial deepening and 3) industrial upgrading. These are key aspects of a positive industrialization process with the aim of achieving increased growth for developing countries. How to achieve these goals in the globalised world of today is the mainstay of SIP and Lauridsen puts forward nine principles in this process. In order to succeed SIP needs: (i) To be part of an overall development strategy; (ii) Support for Diversification, Deepening and Upgrading of the industrial base; (iii) To rest on the gains from technology, collaboration and competition; (iv) A strategic mix of ISI and EOI policies; (v) Strategic and not an unconditional integration into the world market;

(vi) Selective strategy (FITTING); (vii) Institutional pluralism and policy variations; (viii) Requires strong institutional capacities; (ix) Depends on politics.

7

These nine principles reflect a strategic and deliberate choice on part of the policy makers to enhance the manufacturing sector and describe what is needed to achieve this, both in inputs and requirements of political, bureaucratic and administrational frameworks.

Diversification : Industrial diversification includes creating industrial capacity in new geographical areas as well as within previously unexplored sectors. There is a need in latecomer development to mobilize and invest capital in new activities and increase the role of manufacturing in the economy and expand the range of products produced and exported.

8

Increasing the role of manufacture – this can be related to the concept of structural change. It Is when a society moves from the “stage” of primarily an agriculturally based economy towards an

6 Lauridsen:2010:8

7 Lauridsen:2010:24-27

8 Lauridsen:2010:9

8

economy increasingly based on manufacturing that the productivity increases most significantly and brings the population out of poverty.

Indeed Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik 2007 show that if a developing country is able to export commodities that are also produced in developed countries and associated with higher productivity it will be able to grow more rapidly. They therefore assert that fostering an environment that promotes entrepreneurship and investment in new activities will be critical to economic convergence. This will also help developing countries to escape the trap of getting stuck with exporting low-income goods.

9

The aspect of diversification is therefore more important when it comes to leaping to the production of “distant products” e.g. going from sewing machines to cell phones rather than going from shirts to shoes. The important aspect must be that the “new” product must contain a higher degree of productivity to increasingly be able to take advantage of economies of scale and increasing rates of return.

An example of such a leap is that of Toyota which went from the production of textile machinery to car production. This was a great leap and took more than 25 years and many incentives, opportunities and much protection from the Japanese state.

10

Deepening: This aspect refers to policies aiming at building up networks of local suppliers and providers of specialized inputs for industry creating a more interlinked, and complete industrial structure based on the backward and forward linkages of strategic industries.

11

Specialized local service providers, suppliers and contribute to widening the domestic market therefore SIP must aim to balance the supply and demand sides of economies, introducing measures designed to capture more of the value added and allow domestic wages to grow which creates a robust and economy capable of sustaining economic growth. Therefore it is important to stress that the linkages created by industry should be provided domestically. Contrary to this, neoliberal accounts argue for linkages to and integration with the international economy. The programme of SIP calls for institutions and organisations to provide coordination between agents and disseminate knowledge connecting different agents in the domestic market.

12

9 Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik:2007: 23-24

10 Chang:2007:19-20

11 Lauridsen:2010:9-10

12 Ibid

9

Upgrading:

This aspect regards policies focusing at developing a more advanced and competitive industrial structure enabling companies to master more complex technological activities through processes of technological advancement and organizational learning.

13

As we have now shown what the aims of SIP are we will dwell a little at the perspective of what it takes to implement an effective SIP. This regards in particular the eigth of the nine principles listed by Lauridsen. Here he discusses the policy process and the politics attached to this kind of development strategy. In this part he emphasises that: “The policy process attached to SIP is about having the institutional capacity to discover and remedy strategic failures and systemic problems, and about having the institutional capacity to enter the collective search process needed for that.”

14

Another perspective about SIP is that it is intrinsically selective and anticipatory. Because it has to be highly technical and specific in its inputs to key sectors and technologies it has to economise with the scarce resources available. This also means that SIP cannot be the same in all levels of development of a given industry and is markedly different in the start-up phase compared to the sunset phase of the same industry.

15

SIP as it is described here can potentially be a substantial measure for a developing country seeking to improve its position in the global division of labour and hence the living standard of its population. However as it is described by Lauridsen SIP aiming towards a great leap towards higher productivity exports and industry with higher rates of return is inherently difficult and has a built in risks. Any country seeking to majorly shift the base of its economy, risks that the new venture will prove to be a misjudgement of future potentials of a given technology or industrial sector.

Industrial Energy Efficiency

This part will first focus on which barriers exist in the specific area of energy efficiency in industry and since the policy options that UNIDO proposes for developing countries.

The information on specific barriers to IEE is informed by a taxonomy of barriers to Energy

Efficiency which is developed by Steve Sorrell, Alexandra Mallett and Sheridan Nye in a background report for the UNIDOs 2010 - 11 IDR “If industrial energy efficiency pays, why isn’t it

13 Lauridsen:2010:10

14 Lauridsen:2010:26-27

15 Lauridsen:2010:26

10

happening?”. The taxonomy lists six barriers and provides a brief explanation of the background for each of these barriers. (See table 1)

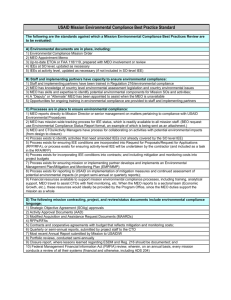

(Table 1: Taxonomy of barriers to energy efficiency)

Barrier

Risk

Imperfect information

Claim

The short paybacks required for energy efficiency investments may represent a rational response to risk. This could be because energy efficiency investments represent a higher technical or financial risk than other types of investment, or that business and market uncertainty encourages short time horizons

Lack of information on energy efficiency opportunities may lead to cost-effective opportunities being missed. In some cases, imperfect information may lead to inefficient products driving efficient products out of the market.

Hidden costs

Access to capital

Engineering-economic analyses may fail to account for either the reduction in utility associated with energy efficient technologies, or the additional costs associated with them. As a consequence, the studies may overestimate energy efficiency potential.

Examples of hidden costs include overhead costs for management, disruptions to production, staff replacement and training, and the costs associated with gathering, analysing and applying information.

If an organisation has insufficient capital through internal funds, and has difficulty raising additional funds through borrowing or share issues, energy efficient investments may be prevented from going ahead. Investment could also be inhibited by internal capital budgeting procedures, investment appraisal rules and the short-term incentives of energy management staff.

Split incentives Energy efficiency opportunities are likely to be foregone if actors cannot appropriate the benefits of the investment. For example, if individual departments within an organisation are not accountable for their energy use they will have no incentive to improve energy efficiency

Bounded rationality

Owing to constraints on time, attention, and the ability to process information, individuals do not make decisions in the manner assumed in economic models. As a consequence, they may neglect opportunities for improving energy efficiency, even when given good information and appropriate incentives.

The nature of these barriers is essentially based on assumptions. These are assumptions on part of financial institutions about the (limited) profitability of a given energy efficiency project that lead to difficulty to obtain loans for investments in IEE equipment as compared to equipment that expands

11

the production capacity of an enterprise. In essence the most of the barriers to IEE refer to the fact that it can be difficult without specific knowledge on energy efficiency to estimate where energy savings can be made. This is in part because that the principal business of an industrial facility is production, not energy efficiency which has significant influence on how the running of an industrial facility is perceived. This is an underlying reason why market forces alone will not achieve industrial energy efficiency on a global basis, despite increasing prices on energy. Two illustrative case examples, shown below, of IEE come from two SMIs

16

in India and Sri Lanka and show how small investments in IEE can be benefitial and cost effective.

Source: Thiruchelvam et al., 2003, 982

There are in fact very high potentials for energy savings, maintenance savings and production benefits which can be realized from systematically pursuing IEE. This has been proven through various cases primarily in OECD countries and when in developing countries most often with support from the development community.

“

High energy prices or constrained energy supply will motivate industrial facilities to try to secure the amount of energy required for operations at the lowest possible price. But price alone will not build awareness within the corporate culture of the industrial firm. It is this lack of awareness and the corresponding failure to manage energy use with the same attention that is routinely afforded production quality, waste reduction and labour costs that is at the root of the opportunity” .

17

16 Small and medium sized industries (SMIs)

17 UNIDO:2008:1

12

The focus on IEE in a development context is aimed at decoupling economic growth from environmental impact by reducing energy intensity in industry and thereby improving its competitiveness. Worldwide industry is responsible for more than one third of primary energy consumption and energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. This portion can be up to 50 per cent in developing countries and often creates tension between economic development goals and constrained energy supply. It is estimated that industrial energy use will grow at a yearly rate of between 1.8 per cent and 3.1 per cent over the coming 25 years. Regarding developing countries

IEE is estimated to be one of the most cost-effective measures to help them meet their increasing energy demand and at the same time loosen the link between economic growth and environmental degradation.

18

In both developing and developed countries energy efficiency in industry is far below what is technically feasible and most favourable in economic terms. The technical potential in industry to decrease energy intensity and GHG emissions is estimated to be up to 26 per cent and 32 per cent which would mean a reduction of 8.0 per cent in total global energy use and 12.4 per cent

CO2 of GHG emissions (IEA).

19

The main IEE policies proposed to developing countries and economies in transition to overcome the barriers to IEE are (i) Target setting agreements; (ii) Energy management standards; (iii)

Capacity building and (iv), Building industrial awareness. Taken together these elements constitute an effective policy package for IEE implementation.

20

Target setting agreements are negotiated between the industrial sector and the government on the basis of an assessment made of each industrial facility are also known as voluntary agreements to reduce energy intensity in industry. The establishment of these, call for a coordinated set of policies providing strong incentive for participating industry as well as technical and financial support and annual monitoring reporting of progress. The best result is achieved through 5 – 10 years legally binding agreements.

21

Energy management standards (EMS) provide guidance to industrial facilities in implementing

IEE into the management process and hence overcoming organisational barriers to IEE. Within companies they require the facility to develop an energy management plan. On part of the state,

EMS require policies and procedures to address all aspects regarding energy purchase, use and

18 http://www.unido.org/index.php?id=1000474

19 Ibid

20 Mckane, Price and Rue du Can:2007:61-66

21 Mckane, Price and Rue du Can:2007:30

13

dispersal.

22

Specific supportive policies and programmes cover (i) voluntary or mandatory standards, (ii) financial incentives for compliance, (iii) available technical assistance, (iv) penalties for non-compliance, (v) recognition programmes, (vi) link to voluntary agreements, (vii) available training on standard compliance and (vii) - industrial systems, (ix) case studies are published, (x) standards are targeted specific plants.

23

Capacity building regards training of local experts in the optimization of industrial systems aimed at providing support to production processes using the least amount of energy while being cost effective.

24

Capacity building in this area is not easy because of its specificity and therefore UNIDO has worked with a group of experts on the field in developing a training curriculum in China. Two years after implementation 22 engineers in the Jiangsu and Shanghai provinces had received training and conducted assessments in 38 industrial plants identifying around 40million kWh of energy savings.

25

Building industrial awareness is of core importance to an industrial energy efficiency programme.

This aspect intrinsically builds on an information campaign introducing key managers in industry to the key concepts in IEE. For this to become effective governments need to build enabling partnerships with i.e. industrial trade associations, technical universities or other strategic partners.

26

2. Analysis:

Challenges of policy implementation in developing countries

This is the most analytical part of the project and will aim to discuss the different aspects of part 1 against some empirical information on the potential of implementing IEE policies and on the consequences this might have, good or bad, for the process of industrial development of developing countries. The intention is to move closer to be able to answer the problem formulation:

“ To which extent do the potentials of Industrial Energy Efficiency coincide with the principles of

Strategic Industrial Policy and the implementation capacity of developing countries and in this way play a valid part of industrial development?”

22 Mckane, Price and Rue du Can:2007:38

23 Mckane, Price and Rue du Can:2007:42

24 Mckane, Price and Rue du Can:2007:47

25 Ibid

26 Mckane, Price and Rue du Can:2007: 65

14

First I will try to assert how the policies of Target setting agreements; Energy management standards; Capacity building and Building industrial awareness coincide with the aims of

Diversifying, deepening and upgrading in SIP. In this regard it seems clear that to a wide extent the

IEE polices recommended by UNIDO resembles the aim of industrial deepening and upgrading the most and to the least extent the aim of industrial diversification. IEE predominantly deals with informing and guiding the already existing industrial players towards a more energy efficient path.

This is not a strategy that directly induces the creation of new industrial sectors notwithstanding although, that the knowledge and the capacities which the capacity building aspect of IEE potentially produces, can be of significance in the creation of sectors relying more on the export of energy efficient technologies. Then again the aim of IEE is energy efficiency and the decoupling of increases in energy use and economic growth and not the creation of a new industrial sector.

However the effectiveness of IEE policies is not a certain fact. It is an implementation heavy task to achieve sustained increases in energy efficiency and difficult even to OECD countries.

Findings that are based on the experiences of implementing IEE by the World Bank Group are put forward by Sarkar and Singh 2010 who also emphasize the challenges of implementing Energy

Efficiency measures and policies especially in developing but also in developed countries. They point to informational, financial, institutional and behavioural barriers to EE implementation.

According to them, the experiences from OECD countries have shown that in order for EE efforts to be efficient the institutional mechanisms must be carefully designed and adapted to suit local needs and conditions. This means that the economic and environmental potential of EE improvements is yet to be realized globally and is yet to provide transformative changes in energy consumption. The case for a strong implementation in this area is proved by the fact that some

OECD countries with relatively strong bureaucracies and policy making institutions have failed to implement these policies effectively in the face of these pervasive barriers.

27

This is an important point to include in this report because it goes to the heart of what the effectiveness of implementing

IEE policies might bring along.

The risk of implementation seems to be higher in developing countries because there are more uncertainties regarding the proper implementation of these policies but as noted earlier the gains will also be higher because of the higher energy intensity in developing countries’ industrial base.

27 Sarkar and Singh:2010:5562

15

On the angle of the desirability of implementing policies and establishing institutions and their link to economic growth Ha-Joon Chang has made important criticisms regarding the content of the recommendations made by the IDPE to the policy makers of developing countries. The main argument he makes is that in many cases the policies and institutions developing countries are encouraged and persuaded to adopt are not the same as the NDC’s used in their own development experience. For instance Great Britain started promoting free trade only after them themselves, by virtue of ardent Infant industry protection and strong protective tariffs had acquired a strong industrial base, able to compete with any foreign enterprise and the United States took the same position when they had become the manufacturing leader.

28

Much of Chang’s recent work has scrutinized, first and foremost the trade policies pursued by the

NDC’s under their development process compared to the policies they recommend to developing countries of today. It is usually accepted that developing countries should adopt what is termed

“good policies” and “good institutions”. “Good policies” are broadly described as (i) restrictive macroeconomic policy, (ii) liberalisation of international trade and investment, (iii) privatization and deregulation. The most important “Good institutions” are (i) democracy, (ii)”good” bureaucracy, (iii) an independent judiciary, (iv) private property rights and intellectual property rights, (v) transparent and market oriented corporate governance and financial institutions including a politically independent central bank.

29

In “Kicking away the ladder – Development policy in historical perspective” from 2003 he compared the trade and industry related development policies of the NDC’s with those they recommend to developing countries of today as well as the institutions these countries had adopted when they were at a comparable development level to developing countries of today.

Here Chang states that:

“Most of the institutions that are currently recommended to the developing countries as a part of the ‘good Governance’ package were in fact the results rather than the causes, of economic development of the NDCs. In this sense, it is not clear how many of them are indeed ‘necessary’ for today’s developing countries” 30

What is emphasised by Chang is clearly that we do not know the exact connection between institutions and growth and that we must understand that the developing countries of today function under better and well tested institutions than the NDCs did during their development experience.

28 Chang:2003:1

29 Ibid

30 Chang:2003:129

16

This is a case to remember when we try to understand how imposing a new policy area and a new set of institutions to the developing countries and certainly it can also be applied in the case of IEE promoting policies and their complementing institutions.

In fact when estimating whether developing countries should adopt the IEE policies promoted by

UNIDO it is fair to try and look at which developing countries have actually attempted let alone succeeded in this area so far. As mentioned in the beginning of this report the task I dealt with during the most of my internship was to track down any IEE policy implemented in Latin America and Eastern Europe. This was an investigation of 13 Latin American countries and 3 Eastern

European countries selected on the presumption that these countries was endowed with heavy industry and had shown interest for energy issues in one way or another and therefore should constitute some of the developing countries who would first start adopting IEE measures of one kind or the other, if this was indeed a viable path. Nonetheless the positive results of this investigation were very few even though many countries had developed elaborate energy saving policies in other area than industry. In fact the most common energy saving measures adopted by these 15 countries is (i) the construction of a ministry in one way or the other responsible for saving and monitoring energy consumption, (ii) the Developments of Codes, Standards and Product

Labelling regarding household appliances and (iii) the provision of Compact Fluorescent Lamps

(CFLs) as a measure of demand side management of electricity. Energy efficiency policies directed at the production process were inherently difficult to find and when projects of this sort had been implemented it was due to the provision of international financing and expertise.

In this context I think it is interesting that IEE was not a priority area even though energy in some countries was very high up the political agenda.

In their 2010 report “Energy Efficiency in Latin America and the Caribbean: Situation and outlook” the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) analysed the situation and the perspectives for energy efficiency in 26 countries of this region. The report studied: (i)

Recent advances in policy, regulatory and institutional frameworks; (ii) key actors in energy efficiency and their effective roles; (iii) resources and funding mechanisms for energy efficiency programmes; (iv) results of energy efficiency programmes to date; and (v) Lessons learned.

31

In this context I will not go into detail with the initiatives in the individual countries but rather dwell on

31 ECLAC, 2010, 11

17

one of the major conclusions drawn in the report. ECLAC states that one of the conclusions emerging most clearly from this investigation is, that:

“the mere existence of energy efficiency legislation in no way guarantees that there will be positive effects on (a rational reduction of) energy demand.”(ECLAC, 2010, 12)

Here the report refers to a need to adapt energy efficiency activities to “national realities” and points out that a systematic implementation is needed in order for these policies to achieve the desired results. On the capacity of the Latin American countries to forcefully implement policies of this kind the report ascertains that:

“The state has difficulty monitoring – and, where the law provides, sanctioning – behaviours that do not conform to legal requirements. Economic and cultural barriers in Latin America and Caribbean societies hinder the full enforcement of energy efficiency standards, while a lack of human resources (due to budgetary constraints) means that monitoring and enforcement systems are inefficient.”(ECLAC, 2010,

12)

Taking this as an example of the difficulty related to the implementation of EE programmes and initiatives, it is clear that if EE and hence also IEE is to be successful, there is a need for careful implementation and for this aspect to be a strategic part of the overall development strategy. The exemption to this characteristic in the region was the two strongest economies Mexico and Brazil.

Sarkar and Singh put special emphasis on the need for strong governance and institutional capacities in achieving positive results in the implementation of EE policies. Poor governance between EE-institutions and related institutions can undermine policy frameworks and initiatives and lead to inability to enforce or govern EE regulations as well as inability to coordinate different levels of government, international community, private sector and civil society.

32

They also point out that a lack of institutions and capacities for (i) public agencies to organize, transform, incentivize and develop new and nascent markets for EE goods and services, and (ii) for local private sectors to adopt EE technologies and practices, are two major barriers to EE implementation.

33

An example of a group of developing countries who have worked on establishing EE standards and labelling for household Appliances is from the Andean Community, which consists of Colombia,

32 Sarkar and Singh:2010:5563

33 Sarkar and Singh:2010:5563

18

Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. What we can learn from this is that even though it is possible for some developing countries to formulate and initiate EE related polices, results are not easy to achieve. The text box below comprises of the main findings of an evaluation of the progress made in the Andean community within this area.

Textbox 1

Notwithstanding the important progress made in Colombia , in particular the Law on Rational Use of Energy of 2001 and the CONOCE programme, there is still a general problem of the low profile of energy efficiency within the energy policy of the country. This implies a continuing struggle to secure the commitment of public and private actors needed to create the conditions for market transformation. A number of steps need to be taken to ensure that the existing and new regulations are properly implemented.

The Government of Ecuador has presented a comprehensive approach, which will focus on the mandatory application of energy efficiency standards and labelling; however, Ecuador is at the very beginning of the process and all the work of developing regulations and test procedures and establishing an appropriate implementation process and infrastructure still needs to be done.

In Peru , there is a need for a specific regulation to implement Law No 27345 on the Promotion of Energy Efficiency.

While the Law stipulates the obligation of merchants and manufacturers to apply energy efficiency labels to their products, a regulation is required to set out how this should happen. A serious problem is the general lack of resources, which impedes higher consumer awareness and stronger commitment of both public and private actors.

The Venezuelan energy efficiency standards and labelling programme has lately been adversely affected by the overrating of the national currency compared to the US Dollar, which resulted in the reduction of national production and its substitution by imports. As a consequence, much of the interest of the national appliance industry to participate in the Technical Standards Committee for Household Appliances ( Comité de Normas Técnicas de

Electrodomésticos ) has been lost. The Government views the reactivation of this participatory process as essential and has addressed the issue of standards and labelling in the draft energy efficiency law mentioned above.

Source: Lutz et al, 2003

As the examples in the text box shows these Latin American countries have had difficulty achieving the energy saving gains they sought for when choosing to implement energy efficient standards and regulations. Comparing this to the policies suggested by UNIDO to gain effects of increased energy security and the de-coupling of increasing energy use and economic growth via IEE it is a clear indicator of the capacities of the Latin American countries regarding policy implementation that they might risk utilising both capital and human resources without achieving the desired goals.

However by virtue of UNIDOs services towards their member countries on this aspect it is clear that the developing countries will not all together stand alone when it comes ot the implementation of IEE.

19

The services offered by UNIDO in the area of IEE, are focused on promoting and supporting a continuous improvement of IEE in developing countries and emerging economies and covers Policy support, policy support, capacity building. The policy support aspect consists of expert advice to policymakers in developing and formulating IEE related policies and programmes as well as technical assistance in developing policy and regulatory frameworks that promote and support the adoption of Energy Management Standards (EMS) by industry. In addition it focuses on assisting in the facilitation of collaboration agreements between public authorities and industrial sectors about energy efficient technologies and best energy management practices.

34

In the area of capacity-building UNIDO carries out Institutional capacity-building regarding the development, implementation and monitoring of IEE policies and programmes and energy management standards. In addition, training programmes on industrial energy systems optimization

(motor, pump, steam, compressed air systems, etc.) and the use and implementation of energy management standards are carried out and project-specific technical assistance which is tailored towards industrial enterprises for demonstration and transfer of state-of-the-art energy systems and energy management technologies.

35

An aspect of UNIDOs support to policy makers can be very positive as it emphasizes the important aspects needed to effectively address the issue of IEE. However it must be noted that this is only a small phase of the process and that the important THE LONG HARD PULL takes place after

UNIDOs experts have left the process and is to be made by the bureaucracy of the individual country. Indeed it is noted by Mckane, Price and Rue du Can that any policy announcement or other type of move from government into a new area like IEE to affect industry will need a period of about a year to be accepted by industrial leaders. Further industry will need a period of 12-18 months to complete an energy efficiency project. In fact one must expect that implementing an IEE programme will take five years as changing organizational behavior takes time and changing general market behaviour takes even longer.

36

Assessing to which degree IEE and SIP will block each other as they both need a strong implementation and support via policy promoted incentives for their respective goals is not certain as some of the aspects of IEE might be supplementing SIP in its effort to create linkages within the

34 http://www.unido.org/index.php?id=1000475

35 http://www.unido.org/index.php?id=1000475

36 Mckane, Price, Rue du Can:2007:61

20

economy and in upgrading industrial production. However it must in this con text be strongly emphasised that what most developing countries struggle with is not yet the upgrading of their industrial manufacturing products but rather to achieve a higher level of industrial diversification and the deepening of the industries already on ground. In these aspects IEE will not necessarily contribute in a positive way but rather there is a risk that if a developing country was in this phase of the industrialisation process the adoption of IEE might inhibit the implementation of active policy support for industrial diversification and deepening.

However putting emphasis on saving energy and hence on how energy is used in industry is by no means a negative thing. There is a close relation between use of energy, the productivity of the general economy and economic growth and developing countries have a unique possibility to avoid following the negative energy intensive industrialisation path used by the NDCs.

3. Conclusion and perspectives

By reviewing these aspects it becomes clear that what to choose in course of industrial development is by no means an easy choice as an increasing amount of factors are presented to the policy makers as inherently important and crucial to the development of their country. However as Chang pointed out there is a strong reason to be skeptical of the recommendations of seemingly plausible economic effects of newly developed policy recommendations and institutional settings. The industrialization process is by virtue a process of choosing between a number of possible paths. This is a choice that inevitably will have long lasting consequences for the potential progress of a country. The renewed concerns for energy in the area of industrial development today contain significantly different aspects than when the NDCs made their development. Therefore the potential gains of adhering to the lessons of history in this area are not as clear cut as regarding other areas of development. With many developing countries struggling with poverty and poor social development performances the aspect of SIP must come before that of IEE.

21

Litterature:

Ayres, Turton and Casten 2006 ,

Ayres and Warr, 2005

Chang, 2003

Chang, 2007

Lauridsen, 2010 -

Lutz et al, 2003

Robert U. Ayres, Hal Turton and Tom Casten “Energy

Efficiency, sustainability and economic growth”, Energy

32 2007 634-648

Robert U. Ayres, Benjamin Warr “Accounting for growth:

The role of physical work” Structural Change and

Economic Dynamics 16(2005) 181-209

Ha-Joon Chang, “Kicking Away the Ladder –

Development strategy in historical perspective, Anthem

Press

Ha-Joon Chang, ”Bad Samaritans – The guilty secrets of rich nations and the threat to global prosperity” Random house business books

Lauridsen, Laurids Sandager (2010). Strategic Industrial

Policy and Latecomer Development: The What, the Why and the How.

Forum for Development Studies , 37(1), 7-32.

Wolfgang F. Lutz, Vicente Garcia, Iván Inocente, Marlene

Palacios, Carlos Valles and Paul Waide

”Energy efficiency standards and labeling of household appliances in the

Andean Community – National programmes and the prospects of regional harmonization”

3 rd

International conference on energy efficiency in Domestic Appliances and Lighting. Draft version 15 May 2003

Mckane, Price and Rue du Can, 2007, “Policies for Promoting Energy Efficiency in Developing

Countries and Transition Economies” – Background paper for the UNIDO side event on Sustainable Industrial

Development on 8 May 2007 at the Commission for

Sustainable Development (Csd-15) – Aimee Mckane, Lynn

Price and Stephane de la Rue du Can Lawrence Berkeley

National Laboratory

UNIDO 1,

“Energy and Climate change, Greening the industrial agenda” http://www.unido.org/fileadmin/user_media/Services/Ener

22

UNIDO, 2008 gy_and_Climate_Change/Office_of_the_Director/UNIDO

%20ECC%20Branch%20Brochure.pdf

“Policies for promoting industrial energy efficiency in developing countries and transition economies” Executive

Summary, Aimee Mckane, Lynn Price, Stephane de la Rue du can, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

World Energy Council, 2009 World Energy Council World Energy and Climate policy ,

2009 assessment “Promoting sustainable energy for the greatest benefit of all”

Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik, 2007,

Ricardo Hausmann, Jason Hwang and Dani Rodrik, ”What you export Matters” Journal of Economic Growth (2007)

12:1–25

Rodrik, 2007,

Rodrik, 2008,

Dani Rodrik, One economics many Recipies:

Globalization, Institutions and Economic Growth,

Princeton and Oxford, Princeton university Press

Dani Rodrik, “Normalizing Industrial Policy”,

Commission on economic growth and development,

Working Paper No. 3 March, Washington IBRD/World

Bank

UN, 1987

Thiruchelvam et al., 2003

Report of the world commission on environment and development – “Our common future”

M. Thiruchelvam, S. Kumar, C, Visvanathan “Policy options to promote energy efficient and environmentally sound technologies in small- and medium-scale industries”

Energy Policy 31 (2003) 977–987

23