Bachelor Thesis

advertisement

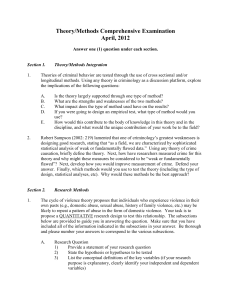

Bordercrime The female participation in (organized) crime and gender-based violence, applied to the case study of Ciudad Juarez. Bachelor Thesis Name: Sanne Rooijakkers Studentno: 3392678 Studyfield: Genderstudies Supervisor: Marta Zarzycka Amount of words: 6000-8000 (Final amount: 7336) Subject: Female participation in crime and the gendering of violence Index Introduction p. 3 Chapter 1: The Causes of the Rise of Female Crime p. 3 Chapter 2: The Gendering of Violence p. 5 Chapter 3: The Case-Study of Ciudad Juarez p. 8 Conclusion p. 13 Bibliography p. 14 Introduction Criminal behavior is mainly participated by men. Or, at least, this is the general perception. Males are considered of showing more antisocial behavior than females.1 But since the 1980’s female participation in crime has been increasing. Various criminologists have had different theories elucidating this phenomenon of men being more present in (violent) crime than females and today’s changing gender differences in participation. In criminal records there is a persistent increase of female arrests and women are more and more involved in criminal activities. In for instance the Italian Mafia and the Nigerian human trafficking market, women are found on ever more prominent positions. However, the overall increase of female participation in crime didn’t stop women from being less victimized. Women and children all over the world are still more likely to be victims of sexual abuse, kidnap and human trafficking. Prostitution is another specific aspect of (organized) crime where it’s usually females who are victim. The victimizing of women and children is part of today’s image of the gendering of violence. Within the two feminist waves, Simone de Beauvoir wrote about females being the Historical Other of males. De Beauvoir argued that the status of females is hierarchical lower than that of men, ever since prehistory. This, according to de Beauvoir is an universal truth, meaning that it’s applicable to all times and places.2 When talking about violence, this gives women the unfavorable position. Speaking of physical capacity, females will usually taste defeat when compared to men. FBI records of 2007 show that in relationship of victim to offender, within family relations, 32.4% of the victims are the killer’s wife.3 But could this be changing since women are participating more and more in (organized) crime? Could the fact that women are more capable of violent behavior themselves count for a shift in the gendering of violence? This theses will find an answer to this question. I’m going to start with question what causes females to get involved in crime by outlining the theoretical framework of feminism and crime, the different theories of feminist criminology taken into account. Then there will be looked at the general gendering of violence and finally both previous subjects will be applied to a case study. This is the case study of Ciudad Juarez, a town direct on the border between the United States and Mexico. This town is said to have ‘Genderwars’, thus the gendering of violence is a prominent factor in. It’s location between respectively rich and poor makes way for corruption, violence, crime and abuse. This is a town of which the economy is in the hands of women, but not of women in leading positions. The economy of Ciudad Juarez floats on the women in the (forced) prostitution.4 Chapter 1: The causes of the rise of female crime Traditional criminology Ever since crime originated, it has been mainly practiced by men. In traditional criminology, different theories attribute the causes of the lack in participation by women Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter and Silva (2001) ‘Sex Differences in Antisocial Behaviour ‘ Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 1 2 Buikema and van der Tuin (2007) ‘Gender in media, kunst en cultuur’ Uitgeverij Coutinho, Bussum, p 22 3 Beirne and Messerschmidt (2011) ‘Criminology: A Sociological Approach’ Oxford University Press, New York, p 34 4 Coronado and Staudt (2005) Resistence and compromiso at global frontlines, University of Texas at El Paso p 140, via http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=irasema_coronado 1 to the biological differences between men and women. Already in 1895 Lombroso and Ferrero argued that there exist external deviations that make people more likely to commit crime. These deviations are less present in females than in males. And moreover, the women that do commit crimes have more similar appearances to males, than to non-criminal females.5 Colleague scholars have found similar theories, all based on comparable motives of biological differences in gender and for decades people have believed in theories of this traditional criminologists. However, when the second feminist wave occurred, some prominent feminists thought they should provide for some alternative theories to gain a better understanding in female crime. This was the time of the 1960’s till the 1980’s and parallel to the revival of feminism, a huge increase in female participation in crime was ascertained. Various feminist scholars claimed to have found explanations for the absence and presence of female appearance in crime within feminist theory. They found the necessity to come up for feminism, since people had bad connotations in regard to feminism. Adler and Opponents in Feminist Criminology Feminist opponents, such as Chesney-Lind, used this connotations to blame feminism for different civil problems. Crime was one of those and since anti-feminist found no resistance in their reasoning, the public bought their arguments.6 That was the time when feminist scholars wanted to make changes to the feminist image. For instance Freda Adler, who developed the ‘emancipation theory’. She argued that the increase of female crime may ran in parallel to the revival of feminism, but that there was no such thing as a cause-effect relation among the two. Feminism, according to Adler, brought along possibilities for women to emancipate themselves. However, not for everybody. Since the Second Wave primarily focused on the differences between men and women and not so much on the differences among women themselves, quite an amount of women felt left behind in the fight for equal rights. It was mainly the white, middleclass female that benefited from second wave feminism.7 Adler argued, that the women who were left behind, developed after the position of men in their own way, providing for more possibilities for women to intervene in the world of criminality. This eventually led to an increase of participation of women in criminological fields of white collar crime, murder and robbery.8 Adler’s theory wasn’t well received among feminist colleagues. For various reasons feminist scholars highly criticized her thinking. They didn’t agree on the fact that feminism indirectly caused women to seek refuge in the world of crime. Pat Carlen stayed more within the thinking of traditional criminologists such as Lombroso and Ferrero, claiming that Adler’s new female potentials in crime were basically the women that were always going to end up in crime. These were women with masculine features, that based on biological similarities to males were more likely to follow a criminal path and had nothing to do with feminism.9 Carlen wasn’t the only scholar who disagreed on the role Adler addressed to feminism. Feminist writer Brown stated she thought Adler provided for a disgrace to feminism. Brown strongly emphasizes on the positive effects feminism brought to the visualization of female crime. According to her, feminism was responsible for the reporting of female crime and therefore the cause for increased Lombroso and Ferrero (1999) ‘The Female Offender’ Rothman Publications, New York Chesney-Lind (1980) 'Rediscovering Lileth: Mysogyny and the 'New Female Criminality', in Griffiths and Nance (eds.) The Female Offenders. Simon Fraser University, New York, p 15 7 Arneil (1999) ‘Politics of feminism’ Blackwell, Oxford, p 155-156 8 Adler (1975) Sisters in Crime, McGraw Hill, New York, p83-84. 9 Carlen (1983) Women's Imprisonment: A Study in Social Control, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, p 376-377 5 6 sentencing for women perpetrators. In addition to that she states that the degree of sentencing (more severe penalties) she uses is more reliable source than Adler’s statistical measures.10 Her critique can placed parallel to that of Beirne and Messerschmidt, who argue: “The second phase of feminist criminology 11 is extremely promising, in particular because of its continuing critique of “malestream” criminology, its own theoretical diversity, its particular varieties of feminist research methodologies, and its welcome inclusion of the study of masculinities. But more importantly, second-phase feminist criminology embraces a social justice perspective that demands we respect diversity; reject male-centered biases; … understand the interconnections among gender, race, class, and age.” 12 They understand the profits gained in the knowledge of female crime, using two directions of feminist theory. First the examination of how women are constructed in and by particular discourses such as the law and second the explorations of women’s actual lives and how their specific problems and responses to these problems influence involvement in crime. In their book they use to example of Smart, who argues in her book ‘Women, Crime, and Criminology: A Feminist Critique’ (1976) how specific law provides for certain discourses that produce gender identities. She shows that law not only constructs different types of women, but also establishes a difference between men and women. 13 In another work Smart expresses her aversion on Adler’s theory, claiming that Adler based her thoughts on scientific sources that are only pretences of the truth.14 At last, Chapman claimed a third reason for the increase of female participation in crime. She claimed that female crime was in strong relationship with labor force participation and that female participation in crime rose in times of economic crisis. This economic misery had nothing to do with feminist influence and therefore the rise in female crime had nothing to do with feminism. Chapman gave facts which showed the relation between recovery of the economy and the simultaneous decrease of arrests. Where Adler stated that female crime had everything to do with the liberation of women and the possibilities this liberation gave, Chapman argued the more logical point of view, that it was economical necessity that drove women into committing crime.15 Thus, among feminist scholars there is not yet found a consensus about the influence of feminism on the increase of female participation in crime. Criminologists on the other hand admit that these feminist contributions are very helpful to understand the motives of the rise of female crime. Chapter 2: The gendering of violence Perpetrators and Victims There is worldwide consensus on the masculine character of antisocial behavior. Antisocial behavior is generally more participated by men than by women and therefore rather associated with masculinity than with femininity. Also taken for granted is the fact that men commonly express their antisocial behavior in violence and violent crime. This might be clarified by the fact that males have greater muscular strength than Brown (1986) 'Women and Crime: The Dark Figures of Criminology', Economy and Society, Vol 15, pp. 355-402. Writer’s note: Second phase feminist criminology meaning the contemporary feminist contributions to criminology from the late 1980’s to the present. (Beirne and Messerschmidt 2011) 12 Beirne and Messerschmidt (2011) ‘Criminology: A Sociological Approach’, p 214 13 Ibidem, p 210 14 Smart (1979) 'The New Female Criminal: Reality or Myth?', British Journal of Criminology, Vol 19, pp. 50-59. P 53 15 Chapman (1980) Economic Realities and the Female Offender, Lexington Books, Mass. 10 11 females.16 Ann Oakley supports this theory. She claims the patterns of male and female crime are connected and structured by patterns of masculinity and femininity. This means that the type and amount of crime committed by each sex express both gendertyped personality and gender-typed social role. In addition she explains the masculinity of crime. “Criminality and masculinity are linked because the sorts of acts associated with each have much in common. The demonstration of physical strength, a certain kind of aggressiveness, visible and external “proof” of achievement, whether legal or illegal- these are facets of the ideal male personality and also of much criminal behavior. Both male and criminal are valued by their peers for these qualities. Thus, the dividing line between what is masculine and what is criminal may at times be a thin one.”17 While female crime has risen since the 1980’s, not only in white collar crime, but also in violent crimes such as robbery and murder, this virile character of crime hasn’t changed. The rise in female participation in crime didn’t evolve in females being less victim of assault. Although females are getting more involved in crime as perpetrators, the female victim rate didn’t decrease. Apparently there is no connection between the two. This leads to the other aspect of gendered violence, the victims. Gender-based violence The high rates in violence targeted against females led the United Nations General Assembly to declare the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women in 1993. This in regard to "the urgent need for the universal application to women of the rights and principles with regard to equality, security, liberty, integrity and dignity of all human beings".18 According to a report in 2000 of United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) on State World Population, at least one third of all women suffer some kind of violence, not rarely by someone familiar. Besides, one fourth of the women suffers abusing during pregnancy.19 These are hard facts, emphasizing the problem that UNFPA calls ‘gender-based violence’. “Gender-based violence is an act that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life. This type of violence affects all types of women around the world, with no specific relation to race, class, ethnicity or age. Genderbased violence encompasses a wide range of human rights violations, including the sexual abuse of children, rape, domestic violence, sexual assault and harassment, trafficking of women and girls and several harmful traditional practices. Any one of these abuses can leave deep psychological scars, damage the health of women and girls in general, including their reproductive and sexual health and, in some instances, result in death.”20 Until recently the issue was considered a private matter, but since the 2003 consultation in Rome it is recognized “as a human rights violation and a public health problem with legal, social, cultural, economic and psychological dimensions.”21 However, because of Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter and Silva (2001) ‘Sex Differences in Antisocial Behaviour ‘, p 4 Beirne and Messerschmidt (2011) ‘Criminology: A Sociological Approach’, p 206 18 United Nations, Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, retrieved February 24 2010, via "A/RES/48/104 - Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women - UN Documents: Gathering a body of global agreements" 19 UNFPD, Report on: Addressing violence against women: piloting and programming, Rome, 15-19 September 2003, via http://www.aletta.nu/aletta/doc/e-publications/2003/Addressing_VAW.pdf#search="gender violence", p 5 20 UNFPD, Report on: Addressing violence against women: piloting and programming, p 15 21 Ibidem 16 17 the domestic environment the violent behavior is acted in, women find difficulties in opening up about their situation. This because of the strong relation between domestic violence and shame and trauma, which should be recognized. Domestic (sexual) violence causes women to become what Diken and Bagge Laustsen call “abject”, an object that provokes disgust and is a threat to bodily and spiritual purity. It leaves the victim and perpetrator, in this case respectively woman and man, in an unequal position towards one another. The woman ends up feeling extremely disgraced and inferior, which is a sign of a prior animal existence, threatening the human identity.22 This leaves women in shame and the issue still covered in silence. Patriarchal power is one of the prime targets in the fight against domestic violence. When male control of females is widely accepted and culturally condoned, this leads to the legitimization of domestic violence.23 And when established, it is hard to get rid of such a system. Organizations trying to gain attention for the issue, such as UNFPA collaborating with governmental organizations, aim for solutions by lobbying for the establishment of specific laws against gender-based violence. Despite all the efforts made by this organizations, actual victim services are still a major flaw. Because of the complex structure of (domestic) gender-bases violence it is difficult to address women directly about it. Even though UNFPA works together with different women’s organizations, women remain in condition of denial. This problem partly lies with health-care providers. They don’t ask frequently enough about domestic violence, however the symptoms sometimes are obviously there. Ranging from female infanticide to spousal abuse, domestic violence can cause health problems such as injuries causing undiagnosable pain, disabilities, disease, depression, eating disorders and anxiety. Besides, it counts for some sexual and reproductive health problems such as difficulties in pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections including HIV/AIDS, miscarriage and maternal mortality.24 The effects of gender-bases violence don’t only impact the lives of the female victims. Indirectly domestic violence has a negative impact on a woman’s functioning in society. This ultimately leads to a negative influence on the economy, as the women’s capabilities are forced down. Logically, people function best when being happy. In addition, necessary but pricy adjustment measures are set up in terms of better medical treatment and other victim services, as well as the formerly discussed improvements in law enforcements and justice systems. Besides, as studies show, children living in households containing domestic violence experience negative examples of a healthy home environment, to such an extent that they are more likely to resort to violent behavior when they become adults. Women in Context Based on the previous, one could argue that although women have faced a change in terms of participation in crime, this didn’t specifically meant a change in the victimization of women. The gendering of violence is still a controversial topic not only for feminists and health organizations, but also for criminologists. Nevertheless, working together made it possible to make a step forward in understanding females in relation to crime and violence. However, the position in which women over the world live, differs enormously. The gender-based violence spoken of before, is domestic violence. This kind of violence happens all over the world, but in the West women nowadays are similar to Diken and Bagge Laustsen (2005) 'Becoming Abject: Rape as a Weapon of War', Body Society, Vol 11, pp. 111-128 UNFPD, Report on: Addressing violence against women: piloting and programming, p 15 24 Ibidem 22 23 men. In some Third World countries this is of a whole other level. In criminology scholars developed the strain theory, claiming that criminality is caused by psychic and social strains. People can feel disadvantaged in their society compared to others and feel the need to counterbalance for that. In order to gain the same successes as others in their society, they turn to illegal ways of gaining money.25 In countries where wealth is divided unequally, this is not uncommon behavior. Since wages are below average in most Third World countries, people are easily tricked into corruption. In the following chapter the theory of both previous chapters are applied in a case study of Ciudad Juarez, a border town lying on the border between Mexico and the United States. One will see Ciudad Juarez is a source of crime, with little respect to human life. Chapter 3: Case Study of Ciudad Juarez Introduction to Ciudad Juarez Ciudad Juarez is a border town situated on the border between Mexico and the United States. The city inhabits over two million people that either live on the Mexican or US side of the border. Because of the different economical positions of the two countries, this causes huge crime rates, specifically on the Mexican side of the border. The actual political border is going through the city, but since there are different locations to cross the border, Ciudad Juarez has become an important route for the smuggling of drugs.26 The northern side of Mexico is well known for its drugs cartels and drugs wars. Earned wages differ hugely in amount comparing the US to the Mexican wages and this fact combined with the presence of drug trafficking leads to a lot of corruption on the Mexican border side. It is every police men’s intention to take care of his family the best he can and this is not established with his regular income. The presence of organized crime groups such as drugs cartels, comes with a high rate of innocent killings. In this metropolis, over the last two decades, more than 300 girls and women have been murdered, of which most of them sexually abused before killed.27 Ciudad Juarez is considered a dangerous and unhealthy domicile for everybody, but specifically for women. Scholars claim the authorities can be held responsible for the poor quality of life, since it has been twenty years since the killings have started and practically none of the murders has been solved. Local authorities and public officials cannot be trusted, because the only thing they care about is their own economical gain in cooperating with the drugs cartels. Female Employment Ciudad Juarez provides for different work opportunities for both men and women. Most apply for women, since female employees are cheaper than male. Women work on both sides of the border in all kinds of jobs. The three main jobs for women are working in maquiladoras, as a maid in El Paso (the American side of the city) or in the prostitution sector. At least forty percent of the women earn money, either formally or informally. Early studies in 1999 showed the average income of Hispanic women in different working sectors. The average income for these women was 11,314 dollar. Obviously, working in a maquiladora didn’t pay much, between 25 and 35 dollars a week. Maids Beirne and Messerschmidt (2011) ‘Criminology: A Sociological Approach’, p 114-117 Zaitch (2002) ‘Trafficking Cocaine’ Kluwer Academic Publishers, The Hague 27 Coronado and Staudt (2005) Resistence and compromiso at global frontlines p 139 25 26 from Ciudad Juarez who looked over children and did housekeeping in El Paso report making that same amount a day.28 The most accessible job for women in Ciudad Juarez is that of working in so-called maquiladoras. These are (mostly) US-owned export-processing factories, facilitated by de Mexican public policies. The maquiladora-system is established by capital investment of American origin, lowering the tariffs and therefore creating cheap employment, especially female. Since the start of this system three decades ago, Ciudad Juarez now counts hundreds of maquiladoras, that, at their high point 2000, provided work for 250.000 workers, of which the majority is female.29 The maquiladora industry has become more diversified throughout its history, which made some jobs are thought appropriate for women, such as electronics, garment, coupon sorting. Other jobs, such as working on car parts, are considered more male. The recruiting of the young females goes through illustrated newspaper advertising that and the use of the feminine and masculine linguistic forms of the Spanish language to state their gender preference.30 Another possible job for Mexican women is becoming a maid at the US-side of Ciudad Juarez, El Paso. The Mexicanas doing this job are usually uneducated women in desperate need for a job to feed their own children. This leads to become a maid in El Paso. However the wages are more appealing then when working in a maquiladora, it is also a more dangerous job. In the US-part of the city, the Mexicanas are basically illegal immigrants. On the other hand, the catching of maids working illegally is not easy, “because Border Patrols agents cannot enter houses without a search warrant, and no magistrate will grant a warrant without strong evidence that the family employs an undocumented maid. The evidence is lacking in most cases.”31 For most Mexican women it is hard to leave their own children behind to go and take care of somebody else’s children. Neighborhoods however, take care of the children as long as their mothers are off working. Besides, Hochschild mentioned in her study on migrating women, that women off to taking care of other children as their jobs, become more affected to their foster-children than to their own. Nannies stated they give the foster-children what they can’t give their own, that these children make them feel mother again and that they spend so much time with these children, it is impossible to not alienate from their own children.32 Besides the ‘proper’ jobs, the crossing border also helped turning the female labor market into a sexual one. Prostitution in prohibited in the United States, but since it is far more easy for North Americans to cross the border to Mexico than the other way round, the Mexican authorities have provided Ciudad Juarez with a flourishing sex market to attract wealthy Americans. Prostitution has become one of the most steady income to the Mexican economy. This means Mexico is depending on women to maintain a constant cash flow. This is established by the inferior status of the female citizens, which are not even fully recognized as inhabitants. Moreover, the police and the policy makers maintain the image of young women as disposable and negatively stereotyped. Women’s predicament is maintained by the globalization of the male-dominated state. The Mexican state will do anything to increase the female position and improve living Fernández-Kelly (1983) For we are sold, I and my people: Women and industry in Mexico's frontier, State University of New York Press, Albany, p 53-59 29 Coronado and Staudt (2005) Resistence and compromiso at global frontlines p 141 30 Fernández-Kelly (1983) For we are sold, I and my people: Women and industry in Mexico's frontier, p 53-59 31 Mendoza (2009) Crossing borders; Women, migration, and domestic work at the Texas-Mexico divide, University of Michigan p 83 32 Hochschild (2005) ‘Love and Gold’, in Ricciutell (2005) For Women, Power and Justice: A Global Perspective, Zed/Innana Books, London, Toronto 28 standards for women as long as that is threatening to the maquiladora system, which is so crucial for its economy.33 Gender Wars and it’s Attention The Mexican government and the female society don’t go along very well, since the former is getting in the way of improving live standards to the latter. The Mexican officials have been trying to adapt to globalization and world economies to achieve a better competitive world market position, but its inhabitants haven’t been able to take any advantage of that. And where Mexican women live in a male-dominated society, they are likely to receive the least of the benefits. One could even argue the presence of gender-bases violence is prominently visible in the region of Ciudad Juarez, since the position of women as such bad, that male inhabitants and male foreigners are able to abuse women without any consequence. This results in over 300 murder cases still being unsolved. The economy of Ciudad Juárez is dependent on the maquiladora system and for the maquiladora system it is dependent on his cooperation with US maquiladora owners of which most of them are involved in some kind of criminal activity. For this cooperation they are dependent on the prostitution sector which is mainly used by Americans and for maintaining the prostitution sector they are dependent on the low position of women, so that there are women to staff the brothels. The low position of women results in the many killings of women, which could well have been carried out by people who are border-crossers and this militates against their prosecution. So the gender inequality is not contained by the porous character of the border, but expanded by it. 34 In a study of Conorado and Staudt, to investigate this gender issue, they found the gender-based violence which they called ‘Gender-wars’ prominent at different levels in the US-Mexican society. There distinguish three levels in which the gender-based violence is occurring. The first levels contains the overt, brutal violence against women, for instance in the sexual abuse and later on killing of women, as that happens in and near Ciudad Juarez, probably on the behalf of the drugs cartels. In the second level they speak of the violence towards women in normalized, everyday violence, women have to face in their daily lives in order to survive along with their families. This can relate to the poor living standards of women and the scarce possibilities for them to find a regular paid job. The third level, they argue, is the level that mentions the conflict between female activists and the uninterested, male-dominated public system in Mexico.35 This refers to the fact that that several activist organizations have shown their interest in helping improve the living standards for people, especially women, in the Northern region of Mexico. Spoken of the earlier mentioned murders, different NGO’s, among them United Nations, Amnesty International and the Inter-American Human Rights Commission, investigated the cases and found out that over hundred murders remain unsolved because either a lack of interest of Mexican federal offices or, again, corruption. Mexican federal officials objected this statement claiming to have conceded negligence due to lack of resources and investigative or technical skills.36 The NGO’s are not the only organizations that showed their interest in the matter. Also the media is important aspect of the gaining of worldwide attention. One of the first widely disseminated documentaries on globalized export processing, Lorraine Gray’s Global Assembly Line, Ibidem Coronado and Staudt (2005)Resistence and compromiso at global frontlines, p 140 35 Ibidem 36 Moreno, Unresolved murders of women rankle in Mexican border city, (December 16, 2005) Washington Post, Washington. 33 34 was filmed on Mexico’s northern border and singer and actor Jennifer Lopez, being a Latina herself, took on the role of Lauren Adrian, a journalist investigating a series of murders near American-owned factories on the border of Juarez and El Paso.37 US Interference It is not just the Mexican government that can be held responsible for the situation, the United States is also part of problem. Practically all maquiladora owners are American citizens, which take no blame for the mess they make. They just push off the instability of Mexico to the presence of the drug cartels. Luis Gutierrez, senior vice president and managing director of AMB Property in Mexico stated “violence in Mexico is an escalation of the fight of drug cartels to gain control of certain markets to distribute to the US and the most of the incidents are among those members.”38 In a way he is right, because the presence of the drug cartels sure have a huge influence on daily life in this part of Mexico, but that doesn’t mean his own company doesn’t contribute to the problem. He and his company keep maintaining the system and therefore are as much part of the problem as the drug cartels. As long as powerful people such as policy makers and factory owners don’t realize that their contribution to the situation in the country counts just as much as the drugs dealers, nothing will change for the habitants of the USMexican border region. Moreover, not just the Mexican government, but also the US government should take responsibility of the happenings in Ciudad Juarez and El Paso. The difficulty here is that they keep pointing fingers at the wrong people instead of taking care of the situation. The owners of the maquiladora factories and the US government name the issue a Mexican problem, so they keep themselves out of blame. The Mexican government will never blame the US, because they might lose the system their economy is depended on and they blame drug cartels, but nobody seems to get that blaming somebody without doing something about it, will never solve the problem. The US government is basically attacking the female body of the nation, since women are considered more vulnerable than men in Ciudad Juarez’s male-dominated system. Several scholar have placed women in the position where they mark the boundaries between different (ethnic) groups or nations. Their bodies function as boundaries through which different groups try to form their identity. “Women are no longer only women, but the personification and symbol of a nation”.39 So in fact, since women are the bearers of nationalistic cultures, the physical attack on women in terms of the murders is an attack on Mexico as a nation is. It seems like to only ones to be affected by this perilous situation are the inhabitants of Ciudad Juarez, especially the women living there and the victims of the unsolved and unnecessary murders. The low position of the women living in that area in terms of class and gender seems the main reason why the phenomenon is occurring in the first place and all the governments are seeming willing to do is maintain this position, thus everything stays the way it is. The only response the habitants of Ciudad Juarez get is help form NGO’s and other activist organizations, but level three of Coronado and Staudt showed that that is one of the things the Mexican government heavily fights. Therefore their attempt to apply political pressure into a change in the IMDB on Bordertown, via http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0445935/ (2011) Borderline, Site Selection Magazine, distributed January, via http://www.siteselection.com/issues/2011/jan/mexico.cfm 39 Griffin and Braidotti (2002) Whiteness and European Situatedness, in: Thinking Differently. A study in European Women’s Studies, Zed Books, pp. 220-236, p 229 37 38Arend transborder strategies, had no impact and made no difference whatsoever40. Thus Coronado and Staudt argue, that it is not the emancipation of women the government aims for, but the increase of globalization to worldwide trading opportunities. And women can’t stand in their way of getting it. Female Participation in Drug Trade As stated in the first chapter, female participation in crime has been increasing since the 1960s and feminist scholars do not have come to a consensus on the causes. International drug trade however, is different from most other types of crime. When looking at the participation of women in drug trade, a whole set of aspects should be taking into account. Applied to the international drug trade, research has primarily focused on men. Lisa Maher investigated the prevalence and role of women in the international drug trade. She made a cluster-analyses regarding two opposing positions. “From one perspective, women in the drug trade are powerless victims driven by poverty and drug addiction. On the other, women are active actors driven by ambition for money and independence, much like their male counterparts.”41 Maher, however, states that these two perceptions are highly simplistic. In her research she displays the multiple inequality such as gender, ethnicity and class reproduces in the drug trade. The drug market in Middle and South America contains more than just the transport and selling of drugs. Peru, Bolivia and Colombia are important countries for the producing of cocaine. Different stages of the production take place in different countries. Whereas the picking of the coca leaves and the cultivations happens mainly in Peru and Bolivia, it is chiefly women that are employed to pick these leaves. In Bolivia, where the leaves are sold, it is also mainly women that are responsible for selling the leaves. These business, however, are considered traditional and legal. As for the illegal part of the drug market, anecdotal evidence suggests that drug laboratories in cocaine and heroin are more male dominated. Although women have been arrested following raids on amphetamine and crack cocaine laboratories in the US, it is not clear whether they were involved or merely present. Women are also involved in the illegal part of the cocaine industry, in the roles of drug mules. Mules are the transnational transporters of drugs. Although it is postulate that most drug mules are women, 60 to 70 percent of the people arrested with drugs at the international borders are male. Also 70 percent of the drug mules who seek medical attention for health problems concerning having swallowed capsules of cocaine or heroin are men.42 However, the former example of mules being arrested at the border could be influence by class justice. It is proven that police and public officials (in the Netherlands) are selective in addressing criminals. Men are more likely to be arrested than females, because they are considered more likely to commit crime. Also for the United States this is true, because black males are most likely to get arrested. Therefore the percentages stated before do not explicitly have to be a representation of the true partition of gender regarding to mules.43 For the motives of mules (researched in Latin America and the Caribbean) it was found that many were single parents, attracted to drug trade because of debts they made. Thus, they are more likely to turn to the criminal path out for economical reasons than because they want to do so. They see no other option. As for Julia Sudbury, Coronado and Staudt (2005) Resistence and compromiso at global frontlines, p 140 Fleetwood (2011) ‘Drug trade’, in Zeiss Stange, Oyster and Sloan (2011) Encyclopedia of Women in Today's, Sage Publications, California, p 428-430 42 Fleetwood (2011) ‘Drug trade’, p 428-430 43 Kat (2002) ‘Klassenjustitie in Nederland’, Nederlandsch Juristenblad, The Hague: Kluwer, vol. 77, afl. 32, pp. 16111613 40 41 neoliberal geopolitics have contributed to women’s participation in drug trafficking, because these have affected women through the feminization of poverty. Nevertheless, drug mules cannot be considered a homogenous group. Besides the women with debts, other mules have claimed themselves to be entrepreneurs or independent traffickers. Again, very little is investigated in this matter and again, it seems to be a maledominated world.44 In regard to the actual drug cartels in the Mexican part of Ciudad Juarez, women may be involved in the drug trade at high level. “Research from Argentina and Mexico suggests that women exercise power at high level indirectly as wives, sisters, and mothers. Anecdotal evidence suggests that women may hold the top positions in some Mexican cartels. Females also can be found in a number of auxiliary roles including recruiting and ‘babysitting’ mules while they travel; training and advising mules, hiding money, drugs and weapons, keeping accounts, receiving packages, serving as brokers and accompanying men as ‘covers’. Evidence from arrests suggests that women work in apparently legitimate organizations where money is laundered. Girlfriends and wives may be arrested as accomplices.”45 This gives a clear view on the participation of women in the cartels nearby the USMexican border. Although the participation can of women is absolutely there, it can be elucidated by these women being closely related to a criminal in terms of relatives or husbands. The role these women play should not be underestimated, as the example shows they take care of a lot of important tasks connected to drug trade. On the other hand, it should be taken into account that these women probably wouldn’t be taking part in criminal business if it wasn’t for their criminal male relation. Even when holding top positions, the women involved in the cartels aren’t likely to stand up for their female counterparts inhabiting the region. Their interest is the economical gain they receive for their lucrative business. Conclusion Because lack of proper investigation (yet), the world considers women in top positions of organized crime an exception. As became clear, most of the criminal world is still considered male-dominated. This gives the women in Ciudad Juarez little hope for quick improvement of their living standards. In chapter one I showed the causes for increased participation of crime considered by feminist scholars. They still don’t have reached a consensus on why this increase occurred. There are two points of view from which one could try to explain women’s participation in crime. On the one hand the focus on the research on how women, in contrast to men, are constructed in society, specifically in context to particular discourses. On the other hand, the actual lives of the women are more taken into account. The focus there lies more on the specific problems and responses in women’s lives and the influence this may have on involvement in crime.46 In the second chapter the understanding of violence against women was explained and why there is not as much attention for it as should be. Besides, the difficulties about dealing with this problem are exemplified. Then, in the third chapter, the two previous chapters were applied to the case study of Ciudad Juarez, a bordertown on the transnational border of Mexico with the United States. Here the horrible position Fleetwood (2011) ‘Drug trade’, p 428-430 Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World Mary Zeiss Stange,Carol K. Oyster,Jane E. Sloan Drug trade. 428-430 46 Beirne and Messerschmidt (2011)’ Criminology: a sociological approach’ p 210 44 45 of women living in that area was exposed, along with the lack of interest on the behalf of governments and public officials. Then the female participation in crime regarding to drug trade and the Mexican drug cartels was discussed. I would say, based on the previous, that the increased female participation didn’t cause a change in the public thought on the gendering of violence. Females are still considered the vulnerable sex and even when they are participating in crime it is mostly out of economical reasons and reasons of unemployment than out of reasons of emancipation and trying to overrule males. Speaking of the Mexican drug cartels, the women involved can staff the higher positions, but this is basically because of either absence of the male counterpart or because there is still high male supervision in terms of male presence of a partner of a son. However, the notion of lack of research on female participation in different areas of crime has come forward multiple times in this article. Further research is definitely in demand. Also the Ciudad Juarez region shouldn’t be forgotten. The more attention it gains, the more likely it becomes for its female inhabitants to see changes being made. Maybe, within the next decennium, Mexican women have followed the Western example of emancipation and are able to improve their living standard. Bibliography (in alphabetical order) (Parts of) Books Adler (1975) Sisters in Crime, McGraw Hill, New York Arneil (1999) Politics of feminism, Blackwell, Oxford Beirne and Messerschmidt (2011) Criminology: A Sociological Approach, Oxford University Press, New York Buikema and van der Tuin (2007) Gender in media, kunst en cultuur, Uitgeverij Coutinho, Bussum Carlen (1983) Women's Imprisonment: A Study in Social Control, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London Chapman (1980) Economic Realities and the Female Offender, Lexington Books, Mass. Chesney-Lind (1980) 'Rediscovering Lileth: Mysogyny and the 'New Female Criminality', in Griffiths and Nance (eds.) The Female Offenders, Simon Fraser University, New York Fernández-Kelly (1983) For we are sold, I and my people: Women and industry in Mexico's frontier, State University of New York Press, Albany, p 53-59 Hochschild (2005) ‘Love and Gold’ in Ricciutell (ed.) (2005) For Women, Power and Justice: A Global Perspective, Zed/Innana Books, London, Toronto Lombroso and Ferrero (1999) ‘The Female Offender’ Rothman Publications, New York Mendoza (2009) Crossing borders; Women, migration, and domestic work at the TexasMexico divide, University of Michigan Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter and Silva (2001) Sex Differences in Antisocial Behaviour, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Siegel and Nelen (2008) Organized Crime: Culture, markets and policies, Springer Science and Business Media, New York Zaitch (2002) ‘Trafficking Cocaine’ Kluwer Academic Publishers, The Hague Scientific Articles Brown (1986) 'Women and Crime: The Dark Figures of Criminology', Economy and Society, Vol 15, pp. 355-402 Coronado and Staudt (2005) ‘Resistence and compromiso at global frontlines’ University of Texas at El Paso via http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=irasema_corona do Diken and Bagge Laustsen (2005) 'Becoming Abject: Rape as a Weapon of War', Body Society, Vol 11, pp. 111-128 Fleetwood (2011) ‘Drug trade’, in Zeiss Stange, Oyster and Sloan (2011) Encyclopedia of Women in Today's, Sage Publications, California, p 428-430 Griffin and Braidotti (2002) Whiteness and European Situatedness, in: Thinking Differently. A study in European Women’s Studies, Zed Books, pp. 220-236 Kat (2002) ‘Klassenjustitie in Nederland’, Nederlandsch Juristenblad, The Hague: Kluwer, vol. 77, afl. 32, pp. 1611-1613 Smart (1979) 'The New Female Criminal: Reality or Myth?', British Journal of Criminology, Vol 19, pp. 50-59 NGO Research Articles United Nations, Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, February 24 2010, via "A/RES/48/104 - Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women UN Documents: Gathering a body of global agreements" UNFPD, Report on: Addressing violence against women: piloting and programming, Rome, 15-19 September 2003, via http://www.aletta.nu/aletta/doc/epublications/2003/Addressing_VAW.pdf#search="gender violence" Newspaper/Magazine Articles Arend (2011) Borderline, Site Selection Magazine, distributed January, via http://www.siteselection.com/issues/2011/jan/mexico.cfm Moreno, Unresolved murders of women rankle in Mexican border city, (December 16, 2005) Washington Post, Washington. Further Research IMDB on Bordertown, via http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0445935/