Talking About Not Talking

advertisement

Talking About Not Talking:

Applying Deming’s New Economics and Denzau and

North’s New Institutional Economics to improve interorganizational systems thinking and performance

(Working Paper Title)

Arthur T. Denzau, Henrik P. Minassians, & Ravi K. Roy

A Paper Presented at

The 52 Annual Meetings of the Public Choice Society, March 12-15, 2015. Hyatt Regency San

Antonio Riverwalk. San Antonio, Texas

nd

Presented in Honorarium of the Legacy of Thomas Borcherding

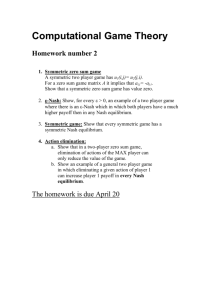

This paper draws jointly on insights from W. Edwards Deming’s Systems of Profound Knowledge

(SoPK) approach and Arthur T. Denzau and Douglass C. North’s (1994) New Institutional-based

work on Shared Mental Models (SMM) to explore how “systems-level” inter-organizational

communication can be facilitated via two means of learning—training and experiential learning

(or learning that occurs through common experience and interaction). In so doing, we apply

Denzau and North’s SMM using a modified version of the Nash equilibrium to operationalize the

learning path to Deming’s SoPK.

Arthur T. Denzau is Professor Emeritus at Claremont Graduate University. arthur.denzau@cgu.edu

Henrik P. Minassians is Associate Professor of Political Science at California State University, Northridge.

henrik.minnasians@csun.edu

Ravi K. Roy is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Southern Utah University and Visiting Scholar at

the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

royr@suu.edu

This is submitted as a working paper. All the usual conditions apply.

Talking About Not Talking: Applying Deming’s New Economics and Denzau and North’s

New Institutional Economics to improve inter-organizational systems thinking and

cooperation

Ravi K. Roy, Arthur T. Denzau, Henrik P. Minassians

Abstract

This paper draws jointly on insights from W. Edwards Deming’s Systems of Profound

Knowledge (SoPK) approach and Arthur T. Denzau and Douglass C. North’s (1994) New

Institutional-based work on Shared Mental Models (SMM) to explore how “systems-level” interorganizational communication can be facilitated via two means of learning—training and

experiential learning (or learning that occurs through common experience and interaction). In so

doing, we apply Denzau and North’s SMM using a modified version of the Nash equilibrium to

operationalize the learning path to Deming’s SoPK.

I.

Introduction: Learning to Think as a System

Communication is essential to cooperation. However, in order for genuine communication

among organizational actors to occur, they must develop a shared awareness of how their

interests may be aligned or interconnected. Where this shared awareness is absent, any attempts

at communication in the name of cooperation are likely to result in a futile “dialogue of the

deaf.” W. Edwards Deming once incisively remarked after a meeting, “we know what we told

them but we have no idea what they heard.” When examining inter-organizational

communication from a systems perspective, it is essential that agents share similar interpretations

regarding priorities, problems and solutions. This is not to suggest however, that actors

necessarily agree on them. Even when agents “agree to disagree” over these things, constructive

relationships remain possible for genuine cooperation if they are speaking and listening to each

other on the basis of shared interpretations.

This raises the question: can agents “learn” to improve cooperation across organizational

boundaries in order to improve the delivery of essential public goods to their citizens? In

exploring this question we draw on conceptual insights from W. Edwards Deming’s Systems of

Profound Knowledge (SoPK) approach and Arthur T. Denzau and Douglass C. North’s (1994)

New-Institutional based work on Shared Mental Models (SMM). The ability to cooperate

depends on effective communication which can only be facilitated through the development of

shared interpretations or mental models. According to Denzau and North (1994), SMMs are

shared cognitive frameworks (or belief systems) that groups of individuals possess and use to

interpret the political and economic environments in which they operate. SMMs also involve

prescriptive lenses as to how that environment should be structured. Not all mental models

however, are similarly accurate or equally valid. The behaviors of political and economic actors

are directly informed by what they “believe” their interests are in accordance with the mental

models they possess. “Rational actions,” therefore, stem from actors’ beliefs about what will

maximize their gains and minimize their losses. As a result, Denzau and North (1994:3-4)

suggest that “the performance of [organizations] is a consequence of the incentive structures put

into place that comprises the institutional framework of the polity and economy”—the system.

Consistently, Deming argued that managers and leaders who are committed to improving both

intra- and inter-organizational performance must adopt a “systems-level” perspective of the

wider organizational environment in which they operate.

The problem is that conversations among public sector organizations across county, regional, and

state jurisdictions are rare. While they may “talk at each other” through official mechanisms

concerning turf and resource disputes, there are few continuous forums that facilitate ongoing

dialogues where they may share their experiences and discuss mutual solutions to common

problems. More critically, many managers and leaders operate in environments that reinforce

closed organizational mental models which prohibit them from seeing the various ways in which

their interests may be interdependent. These narrowspective mental models have detrimental

“blind spots” that may keep these leaders from seeing their many common problems, threats,

opportunities, and financial resources as shared phenomena (in those cases where they actually

exist.). When operating under these narrow lenses, these managers and leaders have little

motivation to cooperate. This is highly unfortunate as these agencies may be missing out on

critical opportunities for shared learning related to what they might be doing right or doing

wrong, or could be doing better. A major part of the problem is that political and market

environments are often shaped by organizations operating in fierce competition with one another

over perceived “scarce” resources. Because of this, public and private organizations regard one

another with high levels of mistrust and suspicion. Tragically, they do not see themselves as

entities in pursuit of mutual purposes but are, rather, often at cross purposes. It turns out that

many departments operating within the same agency think and behave in similar ways, making

interdepartmental communication and coordination within that same agency just as unlikely.

W. Edwards Deming (consistent with Peter Drucker), asserted that well-functioning

organizations characteristically perform their tasks and duties as part of an overall “system” in

the service of a common purpose. According to Deming, listeners at a symphony judge the

overall performance of the entire orchestra; their judgments are not based on the performance of

the individual musicians. Deming goes on to compare a manager within an organization to a

conductor whose role is to get the individual musicians to perform as a system where each

member supports the others (Deming, 1994:96). According to Deming, the purpose of

management, therefore, is to promote organizational effectiveness “in terms of the various

internal and externally interrelated connections and interactions, as opposed to discrete and

independent departments or processes governed by various chains of command” (Deming,

http://blog.deming.org/2012/10/appreciation-for-a-system/).

Deming’s principles can pertain jointly to private firms providing services and products to

consumers as well as government agencies providing public goods to citizens. Deming argued

that managers and leaders must consider how the departments that they oversee both influence

and are at the same time influenced by the other outside agencies and organizations within the

wider political and economic environments in which they jointly operate. Enlightened systems

thinking-based approaches in public administration have been looking at variables related to

building interpersonal trust both within and among organizations. In the private sector, for

example, sports franchise football team owners in the NFL have long operated on the belief that

it is in their interests to cooperate with one another in expanding market share by coordinating

time schedules and so forth. Similarly, industry association leaders in the NFL have coordinated

their season schedules with other sports franchise leagues such as the NBA and the NHL in a

manner that allows them to maximize spectator television viewership and seat attendance year

round (Bellows).

Drawing on insights from Deming’s SoPK and Denzau and North’s SMM, we explore the

obstacles that tend to impede genuine communication among public organizations. Experimental

research in game theory suggests that different players engaging in a common game, who may

start out possessing different interpretations of the interactions they are facing, can end up

developing similar views of those interactions as they continue to play with one another for

extended periods of time. As actors communicate with one another over shared experiences

resulting from those interactions, group learning tends to occur, resulting in shared

interpretations.

We apply concepts from Deming’s SoPK and Denzau and North’s SMM to explore the

importance and relevance of mental models with respect to two means of learning— training and

experiential learning (or learning that occurs through common experience and interaction.)

Denzau, North, and Roy (2007) provided a theoretical schematic outlining multiple possible

NASH equilibria solutions to players in various non-cooperative game scenarios. We explore

here how learning can help facilitate the convergence of discrete subjective individual mental

models into shared inter-subjective mental models—which is the basis of Deming’s systems

thinking and knowledge approach. In so doing, we apply Denzau and North’s SMM using a

modified version of the Nash equilibrium to operationalize the learning path to Deming’s SoPK.

We then conclude this article by applying this novel framework to the realities and possibilities

involved with inter-organization communication and cooperation in Los Angeles County.

II.

Applying Deming’s SoPK as SMMs: Learning to cooperate

County leaders and managers, for example, often go about their business blind to how what they

do and how they do it both affects and is affected by the activities and processes of other agents

outside their own organizations. Getting agents operating within closed organizational cultures to

see the “rationality” of cooperating with those outside their own organization is complicated

because “rationality” is open to subjective interpretation. This is largely because “we never see

the world as it is, but only through the lens of subjectively held mental models” (Denzau and

North, 1993:4) that are acquired through cultural and other types of learning. Inter-subjectivity,

therefore, is something that must be learned. Traditional organizational cultures focus on

improving the parts of an agency rather than focusing on the agency’s function within an

interdependent system. This kind of rationality ignores the importance of addressing problems

originating at the systems level. And while individual organizations, even those that

communicate and coordinate with one another, may not be able to change the system per se (at

least in the short term), they will be better positioned to approach problems and solutions with

improved accuracy, deriving from collective insight and shared expertise.

III.

Learning to Cooperate as Explained Mental Model Shifts in Game Theory:

Three notions of Nash rationality

If managers and leaders operating across various organizations are to begin thinking and

interacting on a systems level, their mental models must change. The shift from “individualist”

subjective mental models towards “shared” intersubjective ones is facilitated by two types of

learning that we can illustrate through game theory--learning the parameters of a given model,

and learning a new model. We then examine mental models with respect to two means of

learning-training and experiential learning. Having explored the two types of learning and two

means of learning, we then suggest how using Denzau and North's (1994) can be used to refine

the Nash equilibrium concept used in game theory in order to illustrate subjective and intersubjective interpretations that actors develop through learning about the organizational

environments in which they interact.

People interact in situations that can be modeled as games in which each player sees the rules

and structure of the game differently in accordance with her own subjective mental model. The

presence of multiple individual mental models that shape an actor’s beliefs about what is rational

behavior and what is not can be illustrated through concepts from game theory. The Nash

Equilibrium used in game theory is a core concept which suggests the optimal strategy an actor

can play relative to the rational preferences and choices of other actors. It has been suggested

that “playing Nash Equilibrium strategies is rational advice for agents involved in one time

strategic interactions captured by non-cooperative game theory” (Risse 2000:361).

Instead of a singular concept of Nash Equilibrium, we propose three: Subjective Nash

Equilibrium, InterSubjective Nash Equilibrium and Objective Nash Equilibrium (hereafter SNE,

ISNE, and ONE, respectively), where ONE is the usual Nash Equilibrium of traditional game

theory. Playing ONE assumes an objective interpretation of a game – the stated game is

common knowledge to all participants, and is objectively true. ONE assumes both that players

see the interaction in the same way and that their understanding of the game and related payoffs

is correct. These theoretical features can be realized in real organizational environments through

the learning that occurs in social interaction. Our conceptual approach takes the possibility of

this reality into account. We illustrate that two players, starting from potentially different views

of the payoff outcomes resulting from interaction and communication, can (but not necessarily

will) arrive at a situation that each believes to be an equilibrium. Learning through interaction

can lead to a common (shared) SNE equilibrium in which neither actor sees any unilateral

strategy as a means to improving their own position. It is possible however for them to discover

they are wrong. In that case, they may learn from the failure of their expectations and make

further changes. If they arrive at a common understanding of the game (albeit possibly wrong),

then they have played to an ISNE (aka a SNE in which both players or agents have the same

mental model of the game.)

Given the subjective game approach, it is easy to see how a positive-sum game, where both

parties can potentially gain from cooperation, can result in failure to achieve those gains. This is

particularly true in cases where actors possess discrete narrow subjective mental models that may

limit their ability to even see the potential of those gains in the first place. Instead, they may

perceive the game as a fiercely competitive zero-sum scenario where neither player gains from

communicating or cooperating. Along the equilibrium path, there may be no reason for either

party to learn that they are misperceiving the game, or even seeing it differently.

Zero-sum perceptions and mental models are characteristically developed and reinforced in

closed, single agency or department-focused, organizational environments. The point being that

in order for those working in such organizational environments to see the incentives of

cooperation of working with others outside that organization, rather than just the costs, they must

begin to think differently. They must learn to think outside the box of their existing individual

mental models. Indeed, they must learn a new mental model. In order for them to maximize the

gains from interaction and cooperation, they must learn the “correct model.” Continuous and

ongoing interactions can help them develop more accurate models.

Purposely exploring the unknown, going off the equilibrium path, can yield feedback that could

result in learning, if the incentives to do so are large enough. Further, communication may enable

the parties to better understand the game as they assess their positions within it as well as further

their learning through training, and examination of similar situations experienced by others.

Investing in such communication and learning is costly, but the payoffs may be large, both

immediately and in terms of creating greater trust and easier interaction in the future. Given such

learning, the parties may be able to move towards at least an ISNE, and even possibly, through

ongoing interaction, a ONE. In such cases, the subjective individualist mental models held by

agents may be shattered, giving way to a new intersubjective equilibrium path.

IV.

Mental Models and Organizational Learning: A 2x2 approach

IV.A

Two Types of Learning

A simple example of game theory involves the so called “prisoner’s dilemma” (PD) in which one

actor attempts to improve her position (or expected utility) at the direct expense of another’s. We

see this play out in many police dramas where two suspects may be caught and taken into

custody, then isolated with the intent of getting each prisoner to confess so that the police can get

a double conviction based on the separate stories of the two accused. However, if both prisoners

were to cooperate in a strategy of mutual silence, then both would presumably go free for lack of

sufficient evidence. In a finite static PD game, the traditional Nash Equilibrium (ONE) is for

each actor to “defect” from a cooperative strategy with the expectation of avoiding the “sucker”

payoff. This is where one prisoner remains silent (cooperates) and hence assumes the whole

penalty while the other prisoner squeals on the silent prisoner in exchange for a lighter charge.

We will use the PD here to illustrate how learning can facilitate a shift in our modified (mental

models-based) Nash solutions— the shift from SNE to ISNE.

IV.B

Two Means of Learning

There are also two different ways to learn—learning of the parameters of a given model, and

learning a new model. We spend years nurturing and training young humans in an attempt to

bestow our culture on them. This type of learning, training, often goes on in the formal settings

of classrooms and lecture halls. Pinker (1994) argues that much of our language is hardwired in,

with the basic grammatical structure given by genetics. Once we start hearing others speak, and

start to learn a specific language, this learning is experiential learning. Such learning can help us

learn the parameters of a given model, choose among alternative competing models (i.e. do

adjectives come before or after the nouns they modify?), or suggest new possible models to

understand the world.

Both training and experiential learning may each be further classified into model learning or

parameter learning. The basic relations among factors can be viewed as a model, and the

particular parameters are details within a model. Some neuroscience approaches to learning

consider the presence of multiple, competing mental models, each competing for attention to

frame our sensual data for the conscious mind (see Minsky, 1986). Model and parameter

learning can occur simultaneously, and in many interactions, large changes in parameters may

change the “model” (as it is referred to here) by which we view the situation.

IV.C

Motivation and Learning

What factors facilitate learning? Economic experiments have demonstrated that learning is

costly. But failure resulting from following existing norms and practices can be even more

costly. As result, failure can often provide strong motivations for actors to learn new ways of

doing things (Denzau and North (1994: 9). To the extent that learning is an evolutionary process,

it may only be through failure of one’s mental models that genuine learning occurs. Indeed,

innovation is often the result of what economists call “destructive learning.” Destructive learning

occurs when our existing mental models fail to deliver on our expectations. It is, therefore,

through the realization of our failures, that we often reassess our existing beliefs and mental

models about the way the world works and begin the search for alternatives. Abject failure often

gives birth to experimentation and innovation.

V.

V.A.

Three Notions of Equilibrium & Learning

Subjective Game Analysis

We consider a subjective game, G, involving a set of players, I = {1, 2, …}, indexed by i ε I. For

current purposes, we simplify to a 2-player setting, with I = {1, 2}. Each player i has a strategy

set, Si, containing the strategies available, and a mental model of the game, Mi(s1, s2), mapping

strategy vectors s into a payoff vector. To fully define a subjective game, we also need the

objective payoff function, Π(s1, s2) mapping to the actual payoffs that players receive at each

play of the game. Putting this all together, we have:

G = {I, {Si}, {Mi}, Π(s)}.

The game has the ONE as a strategy vector, sO, such that for each i ε I, for all ti ε Si,

Πi(ti, sO~i) < Πi(sO).

Now we add in the subjective elements to the analysis. A Subjective Nash Equilibrium, or SNE,

is simply a Nash with each player playing the game their mental models inform them that they

are playing. I.e., it is a strategy vector, s1O, such that for each i ε I, for all ti ε Si ,

Mi(ti, s~i) < Mi(s).

Note that the SNE is independent of the objective payoff function, Π(.).

V.B.

The Relationship Between the SNE and the ONE

Intuitively, it would seem that the subjective Nash and objective Nash are related, but not

necessarily the same. It is clear that if each player possesses the objectively true model of the

game – i.e., for each i ε I,

Mi = Πi ,

then SNE = ONE.

When the mental models of the players are not correct, this need no longer hold. An example

shows this. Suppose that both players’ models are wrong. That is sufficient to yield a SNE that

is not the objective Nash. Suppose that players Row and Column are playing a game with two

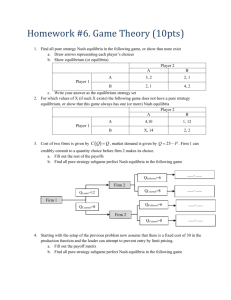

strategy options, Up and Down. The ONE framework of this game is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Up

Down

Left

5, 5

3, 3

Right

3, 3

2, 2

However, we shall assume that each player has their own, incorrect model of the game as shown

in Table 2.

Table 2.

Player Row

Up

Down

Left

3, 3

4, -1

Right

-1, 4

2, 2

Player Column

Up

Down

Left

1, 1

-1, -1

Right

-1, -1

2, 2

Player Row, believing himself to be playing a PD, has a dominant strategy choice of Down.

Player Column sees the game as a coordination game, with two Nash equilibria of {Up, Up} and

{Down, Down}. Believing that Row sees the same game, Column expects Row to play Down,

and consequently plays Down herself. This results in the SNE of {Down, Down}.

At this SNE, both receive the payoff they expect, (2, 2), and each perceives the other player as

correctly choosing, given their mental model of the game. Thus, neither has any incentive to

change behavior.i

V.C

InterSubjective Nash Equilibrium

The mental model a player has of the game may not be objectively true. Thus, between SNE and

ONE are other possibilities. An intermediate case would arise if their mental models were the

same. We term this an Intersubjective Nash Equilibrium, or ISNE. This is simply the SNE of a

game in which for all i, j ε I, Mi = Mj. The previous example showing that a SNE need not be

the ONE is also an example in which a SNE need not be an ISNE. On the other hand, any ISNE

must necessarily be a SNE.

Similarly, any ONE is also an ISNE, but not every ISNE is an ONE. An ONE is a strategy pair

such that neither player can improve their objective payoff unilaterally. At an ONE in which

players believe the objectively true model, the SNE is an ISNE (as they believe in the same

model, the true one).

Summarizing the above results, we conclude that any ONE is an ISNE, and any ISNE is also a

SNE. This can be restated as:

ONE ISNE SNE/

The reverse subsetting may not hold.

V.D

Learning at a SNE

Given that the mental model a player has of the game may not be objectively true, we assume

that there are only two ways in which a player can obtain information about the objective game.

First, the actual payoff received ex post may not be the one expected ex ante:

Πi(s) ≠ Mi(s) for some i ε I.

The second way in which a player may learn that her model of the game is wrong is for the other

player (or one of the other players) to play an unexpected move. If for some j, sj is the choice

that player i believes is j’s best response to the other’s choice of strategy, ti, but player j chose sj’

and

Mi(ti, sj) < Mi(ti, sj’) .

Thus, as player i sees the game, player j could do better for herself by playing sj, but chooses not

to. This gives player i reason to believe that she and player j are looking at different mental

models of the game.

Obviously if the other player’s move cannot be observed or deduced given the player’s model of

the game, no failure of expectations occurs, and there would be no incentive for further learning

due to this. For now, we consider only the situation in which each player’s history is observable

to all players and retained in each player’s memory.

Receiving an unexpected payoff parameter can induce parameter learning, while seeing the other

player choose an unexpected move can induce model learning. This is not an absolute

distinction, as some changes in parameters change the game model, in the sense of what type of

interaction is going on; i.e., am I playing a PD, a coordination game, etc? Thus, unexpected

payoffs can lead to both parameter learning and model learning (Denzau and North, pp. 9, 14).

V.D.1 Myopic Learning

As just suggested, the minimal type of learning is of a single parameter, based on actual

experience of receiving a payoff that differs from the player’s subjective mental model of the

game. Thus, if for some i ε I, at play t of the game,

Πi(st,O) ≠ Mi(st,O)

then it makes sense for a player to update their mental model in t+1 to incorporate this piece of

experiential learning.

By updating the model based on experience, we can avoid a more complicated specification of

how learning might occur. As noted above, myopic learning can result in a player changing her

“model” of the game, in the sense of the class of models we can categorize conceptually. We

consider a game model to be a class of similar games. For example, Prisoner’s Dilemma is a

distinct model of a 2-person interaction from a symmetric coordination game. But myopic

learning has substantial limitations, as it can never enable updating of one’s model of the other

player’s view of the game. Additionally, it only allows learning about payoffs of the outcomes

reached in the history of the game.

What would the ultimate outcome of such myopic learning be? The players would stop at a SNE

such that the ONE payoffs for that outcome are identical to their current mental models of the

game. At such a point, no expectations are unrealized (with respect to myopic learning) and no

further motivation for myopic learning occurs. Of course, a player may have the wrong model

with respect to other outcomes for the other player so that that player does not seem to be playing

rationally at this ultimate myopic learning outcome. But such a result could only cause some

other type of learning, not myopic.

V.D.2 Learning From the Other Player

Suppose that one is at a SNE, and the actual payoff coincides with one’s mental model. Further

suppose that given that model of the game, the play of the other player may not be

rationalizable. How can we proceed to analyze the learning process in this situation? There

seems to be several options. The standard way to deal with this problem is to use the Harsanyi

Transformation of a game of incomplete information, into a related complete information game.ii

The new game adds in a set of types. A type is in our terms a mental model potentially held by

the other player. In other words, it is a one-sided version of the mental models we use here.

Each player then is assumed to have a given set of probability beliefs defined over the possible

types. We feel this is inadequate in several respects. The players must know the types ex ante,

and have common prior beliefs as to their probabilities. Of course, if none of the ex ante types

are objectively correct, then Bayesian learning cannot result in an updating to the objectively true

model (see Blume and Easley, 1982). Of course, if the players realize the tentative veracity of

their mental models, then their play might not correspond to the prescriptions of Nash. If players

are not sure about their model of the game, they may purposely explore the possibilities in order

to learn more about it. With both players doing the same, it may be very difficult for each player

to learn much – the complexity of the situation could greatly increase. This type of exploration

was done by just a few of the players in the Coursey and Mason (1987) study in which

participants were asked to maximize an unknown function. Just as different mental models can

induce different behavior in the same objective circumstances, different players may react to

their lack of certainty in different ways.

VI.

Conclusion

The above illustration suggests an equilibrium path for actors to learn in a manner that enables

them to go from a subjective interpretation of rationality (SNE) to an intersubjective

interpretation or shared rationality (ISNE). Indeed, as we have shown conceptually, Deming’s

systems approach depends on building forms of ISNE across organizations. The core lesson in

this paper is that the switch from SNE to ISNE involves the improved development of shared

interpretations, concepts, and practices that facilitate better communication among agents.

Improved communication, in turn, can facilitate better understanding of the differences that

people may have regarding the meaning of language, symbols, and referents.

To explore our conceptual points in a real world context, let us briefly consider the existing

county structural designs of Los Angeles County and its impacts on cooperation across various

departments serving the same purpose and desiring similar outcomes. To begin with, LA County

is the second largest municipal government in the United States with 10 million residents and

nearly 100,000 public sector employees. In 2006, the county shifted its governance structure

from a Chief Administrative model to a Chief Executive model. Under the new CEO model,

county departments were divided into five clusters, each having unique goals that tie its

organizational structure to the county’s strategic goals and plans. The idea behind shifting the

county governance structure was to increase collaboration between departments regarding design

and the use of performance measures that were hoped to result in better outcomes and

connectivity with the county’s strategic plan. Reliance on different clusters and the design of

department-level performance measures constituted a new attempt to create better intraorganizational metrics and measurement in ensuring accountability (see appendix A).

However, the clustering of departments was based on a general purpose rather than functionality

across programmatic purposes and working relations. These clusters consist of Operations,

Children and Families’ Well-Being, Health and Mental Health Services, Community Services

and Capital Programs, and finally Public Safety. The Department of Children and Family

Services and Sheriffs Department are not part of any of these clusters and, instead of reporting to

the deputy chief executive officer and the chief executive office, they directly report to the

elected body, the Board of Supervisors.

During the past decade, DCFS has witnessed the death of a number of children under their direct

supervision. As seen through the list of different players, county or city or special districts, a

well-being of a child depends upon cooperation of multiple levels of public entities, at the

beginning, and further collaboration of activities when a child or family enters the system. The

main challenge remains that each of these players does not have the same interests, purposes,

functions and responsibilities when it comes to family well-being. Moreover, their approach to

problems remains less systemic and more silo oriented. Appendix B represents a hypothetical

family which at any given point a family member can enter the complex web of various

departments to receive services.

With so many players operating in such a complex environment, the expected belief systems,

mental models and values of competition instead of cooperation has led to a non-systemic way of

thinking and acting. During interviews with the county department heads and former directors of

various departments, one explanation was that collaboration across county departments is sparse

during a crisis since no one wants to own the blame (03/12/2014, 07/10/2014 Anonymous).

Overall, this article argues that the existing design across networks has created differential

multilevel networks of players with their own internal logics which hinder cooperation between

players. Drawing on insight from Deming’s SoPK, we can see that it is important for researchers

and public managers to consider the performance implications of strategic orientations in the

design of structures that encourage cooperation in a network environment to promote improved

managerial coordination. Likewise it also becomes clear that simply creating clusters for

increased collaboration without the actual functional relationship between various county

departments would not automatically lead to better collaboration and/or the creation of multidepartmental cooperation.

What has gone wrong and what needs to be done?

Complex organizational settings and relationships at times encourage certain ways of thinking

and acting. Large complex public or private entities functioning within a network and web of

actors develop their own preconceived assumptions about what’s right and why they are doing

their own activities correctly. If agents operating in separate organizations are to come together

they must develop a common awareness of the importance of cooperating and coordinating with

one another. Developing this mutual awareness will likely require a shift in their mental models

from ones involving independently held “subjective objectives” to shared inter-subjective ones.

Intersubjectivity, therefore is something that must be developed or cultivated. But how? Utilizing

the framework of analysis used to examine these phenomena draws jointly on insights from

Deming’s SoPK and Denzau and North’s SMM to explore the importance and relevance of

mental models with respect to two means of learning – training and experiential learning. But

learning that currently occurs within the county context remains within the same realm of old

paradigm instead of use of permanent question of the assumptions that dictate the logic of

rational action. In other words, learning or learning organizations are the ones that are capable of

moving away from silo and reactive behavior into proactive and interdependent ways of acting

and behaving. Learning organizations should accept failures and promote proactive experiential

approach in addressing public problems.

References

Axelrod, R. (1980a). Effective choice in the prisoner’s dilemma. Journal of Conflict Resolution,

24, 3-25.

Axelrod, R. (1980b). More effective choice in the prisoner’s dilemma. Journal of Conflict

Resolution, 24, 379-403.

Axelrod, R. (1987). The evolution of effective strategies in the iterated prisoner’s dilemma. In L.

Davis (Ed.), Genetic Algorithms and Simulated Annealing. Morgan Kaufman: Los Altos.

Bechtel, W. & Abrahamsen, A. (1991). Connectionism and the Mind: An Introduction to

Parallel Processing in Networks. Blackwell: Cambridge, Mass.

Blume, L., & Easley, D. (1982). Learning to be Rational. Journal of Economic Theory, 26, 34051.

Burns, P. (1985). Experience and decision making: A comparison of students and businessmen in

a simulated progressive auction. Research in Experimental Economics, 3, 139-57.

Camerer, C and Thaler, R. H. (1995). Anomalies: Ultimatums, dictators and manner. Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 9, 209-19.

Clark, A. and Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1993). The Cognizer's Innards: A Psychological &

Philosophical Perspective on the Development of Thought. Mind & Language, 8, 487519.

Coursey, D. L., & Mason, C. F. (1987). Investigations Concerning the Dynamics of Consumer

Behavior in Uncertain Environments. Economic Inquiry, 25, 549-64.

Deming, W. Edwards (1986). Out of the Crisis. MIT Press.

Deming, W. Edwards (2000). The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education (2nd

ed.). MIT Press.

Denzau, A. T. & North, D. C. (1994). Shared Mental Models: Ideologies and Institutions. Kyklos

, 47, 3-31.

Denzau, A.T., North, D.C., & Roy, R.K. (2007). Shared Mental Models Post-script, in Ravi K.

Roy, Arthur T. Denzau & Thomas D. Willett. Neoliberalism: National and Regional

Experiments with Global Ideas. London: Routledge Press.

Hu, Hong; Stuart Jr., Harborne W. An Epistemic Analysis of the Harsanyi Transformation.

International Journal of Game Theory, 30, 4, 517.

Hutchins, E., & Hazlehurst, B. (1992). Learning in the culture process. In C. G. Langton, C.

Taylor, J. D. Farmer, and S. Rasmussen (Eds.), Artificial Life II. Addison-Wesley:

Redwood City, Calif.

Jamal, K., & Sunder, S. (1991). Money vs. gaming: Effects of salient monetary payments in

double oral auctions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 49, 151166.

Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Houghton Mifflin Co.: Boston.

Kreps, D., Milgrom, P., Roberts, J., & Wilson, R. (1982). Rational Cooperation in the Finitely

Repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma. Journal of Economic Theory, 27, 245-52.

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press:

Chicago.

Minsky, Marvin. (1986). The Society of Mind. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Munro, J. F. (1993). California Water Politics: Explaining Policy Change in a Cognitively

Polarized System. In P. A. Sabatier and H. C. Jenkins Smith, Policy Change and

Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Westview Press: Boulder.

Pinker, S. (1994). The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. Wm. Morrow and

Co.: New York:.

Sabatier, P. A. and Jenkins Smith, H. C. (1993). The Dynamics of Policy Oriented Learning. In

P. A. Sabatier and H. C. Jenkins Smith (Eds.), Policy Change and Learning: An

Advocacy Coalition Approach. Westview Press: Boulder.

Sobel, J. H. (1992). Hyperrational Games: Concept and Resolutions. In C. Bicchieri (Ed.),

Knowledge, Belief and Strategic Interaction. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Appendix A

Appendix B

i

. As is commonly noted in games, if out of equilibrium play is not explored, the players may never learn about it.

The Harsanyi Transformation suggested “a method assuming rational players for transforming uncertainty over the

strategy sets of players into uncertainty over their payoffs.” (Hu & Stuart, 2002:517)

ii