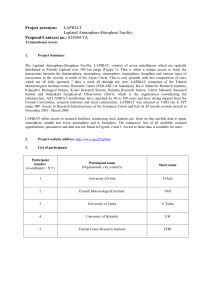

3a. The People as real, ideal, imagined and

advertisement

A STORY OF THE PEOPLE A common spirit and awareness of national existence emerged in Finland during the era of the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland that followed the war of 1808 - 1809 in which Sweden lost Finland to Russia A basis for the feeling of geographical commonality was provided by the joining of Lapland and so-called Old Finland east of the Kymijoki River to the rest of the country. The borders of Finland now began to resemble their present ones The development of communications and industries reduced distances between different parts of the country The feeling of one’s own country was also bolstered by the position of the Lutheran and Orthodox faiths ratified with the influence of the Emperor of Russia, the raising of the Finnish language to equal status alongside Swedish (1902) and the establishment of Finland’s own postal service and its own currency, the markka (1860) as the visible symbols of the nation The image of Finnishness began to take shape at a time when the country still lacked an active art public, art exhibitions or opportunities for thorough art education The Finnish Art Society, founded in 1846 upon private initiative began to stage art exhibitions, laid the basis for the national gallery’s collections known as the Ateneum Art Museum and opened a drawing school in Helsinki alongside a school of painting that had already been founded in Turku Among the increasingly affluent middle class, art and cultural interests became a sign of learning and sophistication. The popularity of genre paintings (scenes of everyday life) and landscapes is shown by the fact that they accounted for up to 60% of all paintings of show in the early exhibitions of the Finnish Art Society Ferdinand von Wright (1822-1906) * In the Haminalahti Garden, c. 1856-57, 43x57, Ateneum Albert Edelfelt (1854-1905) * Under the Birches, 1881 Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931) * First lesson, 1887-1889, 117x98, Ateneum * Country life, 1887, Serlachius Museum Mänttä Eero Järnefelt (1863-1937) Doing the laundry, 1889 Ethnographic fieldwork In his genre paintings, Robert Wilhelm Ekman’s favourite subjects were listeners gathered around the rune-singer Kreeta Haapasalo. In these pictures, different strata of society from the upper classes to soldiers and peasants gather to listen with admiration as this wife of a crown crofter of Veteli sang and played the Kantele Like other artists devoted to the same cause, Ekman based his portrayals of the common people on ethnographic fieldwork, which was a self-evident part of the patriotic activities of the young intelligentsia of the period Arvid Liljelund of Uusikaupunki in Southwest Finland based his folk depictions on material from Ostrobothnia, while Ekman, also originally from Uusikaupunki, undertook his first long study trip to the province of Häme and East Finland in 1846 Material from the trips to the provinces, studies of figures and costumes and interiors of cabins and houses were used as the props and settings of genre paintings. Ekman would also add influences and exotic features from abroad to authentic ethnographic material. The 50-yearold Kreeta Haapasalo recorded during the famine years of 1867 - 1869 was given regular facial features, a straight profile, large eyes and a small mouth. Authentic common people were not accepted as models. Instead, the examples for the figures were sought from the classical heritage of art, the sculpture of Antiquity and the Madonnas of Renaissance painting Arvid Liljelund (1844-1889) * Buyers of regional costumes in Säkylä, 1878, 73x94, Ateneum Robert Wilhelm Ekman (1808-1873) * Kreeta Haapasalo playing kantele in a farmer’s hut, 1868, 75x105, Ateneum * A Band of Gipsies, 1849, 76x100 From the ideal to the real By the second half of the 19th century, the geographical boundary of folk depiction had moved from the regions of Ostrobothnia, Häme and Uusimaa to Karelia, and finally to Northern Finland One group was still missing – there were no portrayals of the Sámi, also known as the Lapps, in Finnish art before the works of Juho Kyyhkynen in 1897 Romanticized folk life became history at the end of the 19th century, when reality replaced idealization, Axel Gallén and Juho Rissanen revealed the earthy and everyday visage of the common people, which some considered to be primitive and malformed. At the same time, an artist group known as Peredvizhniki or the Wanderers, was emerging in Russia in rebellion against conservative tastes in art and demanding art to have the courage to reveal problems in a politically and socially critical vein and to address injustice Akseli Gallen-Kallela was searching for a realistic picture of the finnish people, orientating towards east (Karelia) and north (Savo and Kainuu), finnish speaking areas and population. Inspired by the ideas of Charles Darwin and Hippolyte Taine seeing a man formed by his environment. Also scandinavian literature was an important source of realism (Henrik Ibsen, Hans Jaeger, Christian Krogh, August Strindberg, Minna Canth, Juhani Aho) Eero Järnefelt shows also social reality and living conditions of poor peasants inspired by studies in Russia which made him familiar with Ilya Repins art plus his mother Elisabeth and writer brother Arvid Järnefelt, who like Repin were interested in Leo Tolstoys ideas of social justice and brotherhood between all men Juho Rissanen, on the contrary, came rom a finnish speaking and extremely poor background, with no skills in foreign languages. Interested in ordinary countryside inhabitants, especially their faces, gestrures and everyday life. Developed a stylized style acvording to the teachings of so-called Synthetism, with strong lines and unified colour fields. Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931) * A Boy and a crow, 1884, 86x72, Ateneum * A Woman and a cat, 1885 * Lost (Childbirth in secret) 1885 Anna Sahlstén (1859-1931) * Coffee drinkers Eero Järnefelt (1863-1937) * Slaves of Drudgery, 1893, 131x164, Ateneum Juho Rissanen (1873-1950) * Fortuneteller, 1899, 110x112, Ateneum * Blind woman, 1899, 120x81, Ateneum * By the Pole, 1900, 113x66, Ateneum * Winter fishing, 1900, 125x175, Ateneum The cornerstones of Finnishness In nationalist ideology the cornerstones of Finnishness were folk poetry, popular literacy and religion An important source for the newly found national identity was The Kalevala, folk poetry epic, compiled by Elias Lönnrot (1835 and 1849). Instead of the hero legends of Swedish and Russian rule, the Kalevala offered a purely Finnish mythical past to unify the people The social and moral message of folk depictions was crystallized in their main characters, mothers and children. Nineteenth-century society and art regarded motherhood to be the bearing force of the nation, while children represented its future and continuity. Raising the next generation was the life’s work of women The home, motherhood and children were regarded as naturally suited themes for women artists in particular. In this respect, the landscape painters Victoria Åberg, Fanny Churberg and Helmi Biese were exceptions. On the other hand, a secular Madonna devoted to her child can be seen in Elin Danielson-Gambogi’s and Venny Soldan-Brofeldt’s sensual depictions of motherly love from the early 1890s, and Axel Gallén’s Madonna (1891) showing his wife Mary breast-feeding their first-born daughter Impi Marjatta. Rural society and its art supported traditional gender roles and family values. This situation changed as industrialization and urbanization proceeded and factories and service industries offered jobs and income from outside the home also for women, which permitted women to live independently In 19th-century Finland, the image of an independent woman with power was personified by Louhi, the Mistress of Pohjola or the Hag of the North and her daughters in the Kalevala epic. Louhi of the Defence of the Sampo (1896) by Axel Gallén is a demonized hybrid of a sphinx and a griffin, an actively attacking witch, a woman corrupted by her desire for power and a challenge to the male world order Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931) * New building, 1903, tempera, 77x145, Ateneum, a preliminary work for the Juselius mausoleum Albert Edelfelt (1854-1905) * A Child’s funeral, 1879, 120x240, Ateneum * Women by the Ruokolahti church, 1887, 129x158, Ateneum * Rune singer Larin Paraske (Paraskeva Nikitina), 1893 * Old woman with a basket, 1882, Ateneum Alvar Cawén (1886-1935) * Eeva-Stiina, 1925, 81x65, Ateneum Pekka Halonen (1865-1933) * Washing clothes in an ice hole, 1900, 125x180, Ateneum, painted for the World Fair exhibition in Paris Exemplary models, heroes and confrontations In 19th-century art exemplary individuals raised to national prominence were mostly representatives of art, culture and sciences, industrialists, or the heroes of history or the national epic In the early years of national independence after 1917, influential figures of art and science began to make way for sports heroes The concept of the people had become strained when the declaration of independence by the Finnish Senate in December 1917 was followed by the outbreak of a civil war in January 1918. The civil war was a national tragedy that shut Finland for years into an introverted atmosphere dreaming of the past. In the early years of the young Republic of Finland, the country’s leading sculptor Wäinö Aaltonen gave Finnish identity a bold new appearance, with the example of Ancient Greece as his inspiration. In his works, the “Finnish race”, classified as eastern in scholarly writings of the late 19th century, was given pure features and an athletic anatomy Aaltonen’s imagery lent support to classical Western ideals of beauty, while the painter Tyko Sallinen’s conception of his fellow man was of a rougher, and even more base, nature. In the early years of independence, these two extremes of art divided the opinions of viewers in the same way as the political developments of the time. The figures depicted in Sallinen’s art – the laughing Karelian peasant women in The Washerwomen (1911) and the ecstatic believers of The Fanatics (1918) – were an affront to the general public and art critics alike, as they were regarded as distorting the common people into vulgar and barbaric caricatures. But neither was Wäinö Aaltonen universally accepted, for his political connections and the monuments designed by him for the winning White side of the civil war tore at the wounds left by confrontations within the nation On the other hand, everyone could agree about the country’s internationally successful sportsmen, and no one denied the achievements of the “Flying Finns” Hannes Kolehmainen (1899 - 1966) and Paavo Nurmi (1897 - 1973) in athletics in the Olympic Games. Wäinö Aaltonen’s statue of Paavo Nurmi from 1924 became one of the most enduring symbols of Finnish identity. A cast of this work has stood near the Olympic Stadium in Helsinki since the 1952 Olympic Games, and another copy has been in Itäinen rantakatu street in the centre of Turku since 1955 Marcus Collin (1882-1966) * Harvest, 1915, 90x98, Ateneum Tyko Sallinen (1879-1955) * Washerwomen, 1911, 154x136, Ateneum * Jytkyt, 1918, 114x138, Ateneum * Religious fanatics, 1918, 168x185, Ateneum Wäinö Aaltonen (1894-1966) * Statues in the Parliament house: Settler, Mental work, Future, Faith, Harvester, 1932 Working for the future In addition to sports, war surprisingly became a factor of unity dispelling the conflicts of class of the young nation. The wounds of internal confrontation began to heal as a result of repelling the threat of the Soviet Union in the Winter War of 1939 - 1940 and the so-called Continuation War of 1941 - 1944. Divided in the process of gaining independence, the country now found a shared tale of heroism, the story of national survival. In his Finlandia frescoes (1939 - 1943) made during the war for the Bank of Finland, Lennart Segerstråle depicted “the awakening of the Finnish people from an unknowing state of nature and the darkness of history into light”. The equestrian statue of Marshal Mannerheim (by Aimo Tukiainen) in the centre of Helsinki can be regarded as the culmination and end of this heroic period. The statue was realized through donations and a public collection of funds. The competition for the project was won by Tukiainen in the 1950s and the solemn unveiling of the work took place in 1960 Heroism was followed by decades of change. Along with the new era came masses of workers in the cities. The Finnish countryside was depopulated, the towns and cities grew Tove Jansson (1914-2001) * Frescoes in the Helsinki City Hall restaurant, 1947 Michael Schilkin (1900-1962) * Market place, relief in ceramics from the Helsinki City Hall restaurant, 1947 Greta Hällfors-Sipilä (1899-1974) * A Summer day, 1922 Rudolf Koivu (1890-1946) * Illustrations for children’s books, fairytales and postcards Martta Wendelin (1893-1986) * Illustrations for magazine covers and postcards, f.ex. Kotiliesi magazine - ”Elovena girl” from Martta Wendelin Kotiliesi magazine cover, August 1941 to Oatmeal package and the art of Jani Leinonen (born 1978)