Future directions for native vegetation in Victoria – Consultation

advertisement

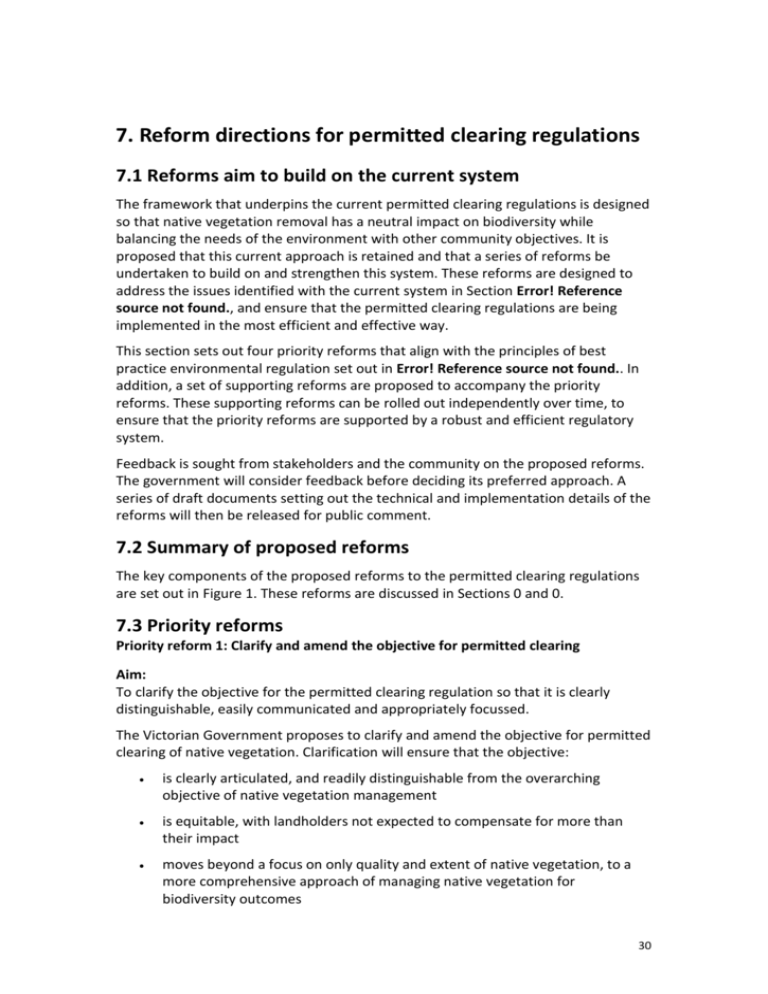

7. Reform directions for permitted clearing regulations 7.1 Reforms aim to build on the current system The framework that underpins the current permitted clearing regulations is designed so that native vegetation removal has a neutral impact on biodiversity while balancing the needs of the environment with other community objectives. It is proposed that this current approach is retained and that a series of reforms be undertaken to build on and strengthen this system. These reforms are designed to address the issues identified with the current system in Section Error! Reference source not found., and ensure that the permitted clearing regulations are being implemented in the most efficient and effective way. This section sets out four priority reforms that align with the principles of best practice environmental regulation set out in Error! Reference source not found.. In addition, a set of supporting reforms are proposed to accompany the priority reforms. These supporting reforms can be rolled out independently over time, to ensure that the priority reforms are supported by a robust and efficient regulatory system. Feedback is sought from stakeholders and the community on the proposed reforms. The government will consider feedback before deciding its preferred approach. A series of draft documents setting out the technical and implementation details of the reforms will then be released for public comment. 7.2 Summary of proposed reforms The key components of the proposed reforms to the permitted clearing regulations are set out in Figure 1. These reforms are discussed in Sections 0 and 0. 7.3 Priority reforms Priority reform 1: Clarify and amend the objective for permitted clearing Aim: To clarify the objective for the permitted clearing regulation so that it is clearly distinguishable, easily communicated and appropriately focussed. The Victorian Government proposes to clarify and amend the objective for permitted clearing of native vegetation. Clarification will ensure that the objective: is clearly articulated, and readily distinguishable from the overarching objective of native vegetation management is equitable, with landholders not expected to compensate for more than their impact moves beyond a focus on only quality and extent of native vegetation, to a more comprehensive approach of managing native vegetation for biodiversity outcomes 30 relates specifically to native vegetation for biodiversity in the planning system. The proposed amended and clarified objective for permitted clearing in Victoria is set out below. Objective for permitted clearing of native vegetation in Victoria: No net loss in the contribution made by native vegetation to Victoria’s biodiversity. This objective creates the framework for permitted clearing to have a neutral impact on biodiversity. To achieve this objective the following should occur: native vegetation removal should generally not be permitted if it has a significant impact on Victoria’s biodiversity that cannot be satisfactorily offset clearing is avoided or minimised where environmental costs, as reflected in the offset costs, outweigh the value of the alternate land use when native vegetation removal is permitted, offset requirements will deliver a neutral outcome for Victoria’s biodiversity. The intention is that the objective for biodiversity be distinguishable within the permitted clearing regulations. The objective of permitted clearing regulations will be clearly set out in the Victoria Planning Provisions. This will enable the biodiversity objective to be considered in integrated decision making alongside other native vegetation related objectives. Proposed action 1.1: Clarify and amend the objective for permitted clearing in policy documents, and in the State Planning Policy Framework and the relevant Particular Provisions in the Victoria Planning Provisions. 31 Figure 1 Reform directions for permitted clearing regulations Figure summarises the proposed priority and supporting reforms for the permitted clearing regulations. Priority reform 2: Improve how the biodiversity value of native vegetation is defined and measured Aims: Reduce costs and improve accuracy in measuring the biodiversity value of native vegetation through improvements in mapping and modelling approaches, and the site assessment method. Reduce regulatory burden faced by landholders and government by greater use of mapped and modelled data, and reduced reliance on site assessments and consultants’ reports. Provide greater certainty for landowners by improved information provision upfront. Improving our understanding of the value of native vegetation for biodiversity can assist in more accurate and consistent decision making, and better targeted offset obligations. In addition, providing accurate information upfront about the biodiversity value of land to landholders, assists them in making informed land-use 32 decisions. Improving information and its accessibility reduces the administrative burden related to information collection and uncertainty of obligations. Value of native vegetation for biodiversity at the landscape scale Since Victoria’s Native Vegetation Management – A Framework for Action was introduced in 2002, there have been developments in our scientific understanding of: the biodiversity value of native vegetation the role played by native vegetation in maintaining biodiversity the threats facing native vegetation the tools and technology available to measure biodiversity value and assist decision making. The current permitted clearing regulations use conservation significance as a measure of the value of native vegetation that is not captured by its quality and extent. Conservation significance is a broad, criteria-based categorisation of vegetation. The categorisation is informed by a combination of the rare or threatened status of the vegetation type and its quality, the presence of habitat for rare or threatened species, or other attributes.1 There is an opportunity to design a new system that is based on current scientific understanding and tools, and which can better distinguish the relative strategic value of native vegetation in different locations in the landscape. Proposed improvements include: prioritising locations for their biodiversity value at a statewide level, using the spatial modelling approaches that inform NaturePrint (see below for details) moving from using point data and subjective decision criteria to define rare or threatened species habitat, to using Species Distribution Models (SDMs). These are predictive maps which show the suitability of a location for a species based on its geographic variation better identification of localised sites of importance for rare or threatened species, and greater understanding of the potential consequences of clearing these sites. NaturePrint – Strategic Natural Values 2.0 Developed by DSE, NaturePrint prioritises native vegetation assets across Victoria. It is an interactive model that brings together large amounts of information collected about species presence, habitat quality and connectivity, to determine relative environmental value across the landscape. This model ranks locations for their potential to contribute to the efficient conservation of the full range of Victoria’s biodiversity. Biodiversity value of native vegetation at the site level 1 Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Victoria’s Native Vegetation Management: A Framework for Action, Melbourne 2002, Appendix 3, p. 53 33 In the current system, the Habitat Hectares methodology is used to measure quality and quantity of native vegetation at a site. These site-based assessments can be time consuming and subject to assessor variation. Opportunities for improving the methodology have been identified that can reduce assessor time and increase the accuracy and consistency of information the assessment provides. Proposed improvements include: focussing the methodology on capturing and validating the quality of the vegetation on site, with contextual factors (such as landscape context) determined using spatial models which more accurately incorporate landscape values embed and better utilise technology in the assessment process to allow for integration of more complex calculations and to reduce user error modify the scoring approach and calculation to allow for better reflection of relative value, and for distinction between sites. Spatial models offer the opportunity to reduce the cost and improve the accuracy of information used to support decision making. For low impact clearing spatial models can replace complex site-based assessments. However, when the impact of a proposal is considered high, or the site is identified as providing high strategic value, site assessments will be required to augment or validate modelled information (see priority reform 3). Providing information on value Comprehensive information about the value of native vegetation on their land should be readily available to landholders interacting with the regulatory system. Providing access to biodiversity information helps landholders to understand their potential permitted clearing regulatory obligations upfront. This allows for more informed planning and investment decisions, and assists landholders to develop plans that avoid and minimise native vegetation removal. The government is best placed to efficiently provide systems to define and measure value, drawing on economies of scale and specialisation, and ensuring consistency and independence. It is proposed that improved spatial information about the value of native vegetation be made readily available to the community. Proposed action 2.1: Develop a purpose built information system that measures biodiversity value and prioritises locations across the state for conservation. This system can inform application assessment pathways, decision making guidelines and offset requirements. Proposed action 2.2: Map locations in the landscape for their importance as habitat for rare or threatened species. Proposed action 2.3: Update the Habitat Hectares methodology so that it incorporates current technology and scientific understandings of biodiversity. 34 Proposed action 2.4: Improve publicly available information on the biodiversity values of locations. Priority reform 3: Improve decision making Risk and proportionality in decision making Aims: Protect high value biodiversity assets through targeting the mitigation hierarchy to situations where the impact of native vegetation removal is highest. Reduce regulatory burden for the majority of landowners by simplifying the permit process for low impact clearing, which accounts for the largest proportion of permit applications. Reduce administrative costs for government and better protect native vegetation of high biodiversity value by targeting resources where the impacts of clearing are highest. To enable the permitted clearing regulations to provide both efficient and equitable outcomes, it is proposed that risk and proportionality are more firmly embedded in the regulatory system. Incorporating risk and proportionality into the permit application process and decision making ensures that obligations and costs faced by landholders better reflect the biodiversity impact of their clearing proposal. The characteristics of native vegetation that define its importance for maintaining biodiversity are highly varied. Therefore, it is not effective or efficient to impose a one-size-fits-all approach to regulating native vegetation removal. The value of native vegetation on a particular site is determined by its quality and extent, and also its importance for the persistence of species of flora and fauna. Species persistence is the continued existence and diversity of a species into the future. The importance of native vegetation for species persistence could relate to the rarity of its type, whether it is habitat for a threatened species, or if its location is strategically important in the landscape. Figure 2 shows the different characteristics of native vegetation that drive its importance for biodiversity, and therefore the level of impact that removing it could have. 35 Figure 2 Characteristics of native vegetation that determine its biodiversity value Figure shows the characteristics of native vegetation that is a combination of either high or low importance for species persistence and high or low quality and extent. It is proposed that applications to remove native vegetation be processed according to the biodiversity impact of the proposed native vegetation removal, and that this approach is formalised in the planning system, It is further proposed that risk-based pathways determine what information is required to assess permit applications. With improved mapped data and prioritising tools available to inform decisions, the need for site assessments can be better targeted. For low risk applications, decisions can be based on mapped and modelled information without requiring a site assessment. This would reduce costs for a large portion of permit applications that are low risk (see Error! Reference source not found.). Risk-based pathways for application processing can ensure that regulator resources are focussed on the small number of applications that have the bulk of the environmental impact. It is also proposed that the risk-based pathways determine how the mitigation hierarchy is applied. This would involve a shift of focus in applying the mitigation hierarchy: away from the input-based approach, where all applicants are required to demonstrate that clearing has been avoided and minimised 36 towards an output-based measure that considers the effect of the clearing on biodiversity. The mitigation hierarchy should be applied in a manner that considers: the type and impact of the clearing proposal the costs and benefits of retaining native vegetation within the context of its surrounding landscape, and its long term viability. A permit for native vegetation removal should generally not be granted when removal is considered to have a significant impact on a biodiversity asset, and it is unlikely that offsets are available or can provide acceptable compensation for the loss of native vegetation. When native vegetation removal can be satisfactorily offset, the cost of offsets provides an incentive for proponents to develop plans which minimise impacts on native vegetation. This would be supported by more accurate information on the value of the native vegetation being provided to permit applicants, along with assistance in understanding their potential impacts on native vegetation and how these can be minimised. Improved functioning of the offset market, including better information on price and offset availability (discussed in Section 7.4), also assists permit applicants to make informed decisions that minimise native vegetation removal, and reduce their offset requirements and costs. For low risk applications, it is proposed that demonstrating avoidance and minimisation would not be required, and a permit would be granted provided a compliant offset is obtained. It is envisaged that this change would simplify and streamline low risk permit application processes and reduce costs. As the majority of applications are for low impact clearing, a formalised risk-based pathways approach is expected to significantly reduce the regulatory burden faced by both landholders and government. In these cases landholders will be able to undertake a simplified and expedited permit approval process. Risk-based pathways in practice In response to the 2009 VCEC report A Sustainable Future for Victoria: Getting Environmental Regulation Right, the Victorian Government committed to the introduction of a risk-based approach for assessing native vegetation permits. This approach aligns the complexity and cost of the permit application process to the biodiversity impact of the proposed removal of native vegetation. To deliver on this commitment, DSE has developed an approach to streamlining permit applications to remove native vegetation on the basis of their expected risk and impact. This has included developing low, moderate and high risk application categories based on the extent of native vegetation that is proposed to be cleared, and the presence of ‘highly localised assets.’ Highly localised assets are areas of high environmental significance where modest levels of vegetation removal may have significant impacts. For low risk permits, the assessment relies on existing mapped and modelled data, coupled with non-specialist information provided by the applicant. This has reduced 37 the need for complex and costly consultants’ reports. In addition, demonstrating strict compliance with the mitigation hierarchy is not required, in recognition of the low risk nature of the proposed clearing. To date the application of the risk-based pathways has been limited to DSE referred permit applications and this approach is not formalised in the planning system. Focussing on biodiversity outcomes in decision making The proposed amended objective of the permitted clearing regulations focuses the purpose of the regulations on the biodiversity outcomes delivered by native vegetation. To deliver this biodiversity objective, the decisions made and obligations imposed under the regulations should clearly consider the biodiversity aspects of native vegetation. Other benefits that native vegetation provides, such as land and water protection, can continue to be considered as part of the application process for a permit to remove native vegetation. However, it is proposed that this consideration be clearly distinguished through separate fit-for-purpose decision guidelines, and not be informed by the biodiversity related rules and guidance material. It is proposed that the native vegetation for biodiversity decision guidelines and offsetting requirements be amended so they focus on protecting and maintaining Victoria’s biodiversity. A clearer distinction between considering native vegetation for biodiversity, and for other purposes, would also improve the functionality of the regulations. This includes providing clarity about the basis on which decisions are made, and ensuring that conditions placed on a permit are focused on the outcomes desired. Proposed action 3.1: Embed in the planning system a tiered, risk-based approach to processing applications for permits to remove native vegetation, including what information is required to be provided. Proposed action 3.2: Update the permitted clearing decision making guidelines to better facilitate consistent outcomes and risk-based decision making. Updates should include: applying the mitigation hierarchy based on the risk and impact of the proposal to remove native vegetation considering the relative costs and benefits of retaining, or removing and offsetting native vegetation over time. Proposed action 3.3: Develop separate decision making guidelines for considering native vegetation removal in relation to biodiversity outcomes, and for other outcomes. 38 Priority reform 4: Ensure offsets provide appropriate compensation for the environment Aims: Provide protection for native vegetation of high biodiversity value by ensuring that offsets are appropriately tailored to mitigate impacts of native vegetation removal. Direct offsets towards areas that are likely to have higher strategic biodiversity value in the long term by creating incentives for landowners to offset in areas that are more strategically valuable. Reduce costs to landowners by providing simplified and more flexible offset arrangements for low impact clearing, which makes up the majority of permit applications. To meet the ‘no net loss’ from permitted clearing objective, when clearing is permitted to occur it is required that offsets are secured that deliver gains in native vegetation that are equivalent to the losses that have occurred. It is proposed that new stratified offsetting rules be developed that: provide compensation for the environment that better reflects the value of the native vegetation removed impose obligations and costs that are proportionate to the value of the native vegetation that is proposed to be removed. 39 Figure 8: Biodiversity value of native vegetation and corresponding offset requirements Figure shows offset requirements for the removal of different types of native vegetation. These proposed offsetting rules would be informed by the improved tools for measuring biodiversity value, discussed in priority reform 2. The rules would have regard to the quality and extent of native vegetation and indicators of its importance for species persistence. These outcomes would be achieved through the following approaches: when the vegetation being removed provides important habitat for rare or threatened species, the corresponding offset requirement would provide targeted outcomes for those species when the native vegetation is not important for the persistence of rare or threatened species, offsets would be based on the strategic importance of the vegetation being cleared. This would create the opportunity to focus offsetting in areas that are most strategically important for maintaining Victoria’s biodiversity. This approach would be likely to result in improved and longer lasting biodiversity outcomes than the current approach which focuses on maintaining the status quo through either in situ conservation, or replication elsewhere for native vegetation removal with low impacts, offsetting requirements would be more flexible and be met through simplified processes. For example 40 increasing options to offset on site or pooling multiple small offsets at larger sites through over-the-counter offset schemes. Figure 3 illustrates the characteristics of native vegetation that determine its importance for biodiversity and the proposed corresponding offset requirements. Figure 3 Biodiversity value of native vegetation and corresponding offset requirements Figure shows offset requirements for the removal of different types of native vegetation Proposed action 4.1: Develop new risk-based offsetting rules that are organised around the strategic priority of locations in the landscape. These rules include: requiring the offsets to closely match the type of vegetation cleared where rare or threatened species habitat is affected for permits to remove native vegetation that have low biodiversity impacts, providing flexible offsetting options, that still deliver targeted environmental outcomes where matching of clearing and offset is not required, creating incentives that direct offsets to areas of high strategic biodiversity value for the state. 7.4 Supporting reforms Alongside the four priority reform areas discussed in Section 7.3, the review of the permitted clearing regulations also identified five further areas for improvement. These five areas can be pursued independently, over the medium to long term (see Figure 1). Some of these additional areas for improvement extend beyond the native vegetation permitting process and are applicable to broader native vegetation policy. Supporting reform 1: Define state and local government regulatory and planning roles Local governments have primary responsibility for land use planning in their areas, including responsibility for zoning and overlays, which should accurately identify areas for environmental protection and areas for development. This planning plays an important role in the functioning of the permitted clearing regulations. There are opportunities for DSE to work with local government to improve the application of these tools, to ensure that they are accurate, reflect natural values and allowed uses of land, and are complementary with statewide legislation. Improved spatial information about natural values should facilitate this process. The role of DSE in the development and designation of overlays, and as a referral authority, could also benefit from reassessment and clarification. Local policy frameworks should clearly differentiate local policy for protecting native vegetation to achieve local objectives (for example, amenity, or local environmental concerns) from the Victorian Government’s native vegetation policy. Where decisions about retaining native vegetation or about offset requirements are based on local policy 41 objectives, these decisions should be clearly attributed to the local government’s objectives. Developing guidance material about the roles and responsibilities of state and local government will improve clarity in both native vegetation policy development and implementation. Clearer demarcation of policy purposes and responsibilities should enable landholders to better understand the basis on which native vegetation planning decisions are made. This improves accountability and ensures that clear paths of recourse for decisions are available under both Victorian Government policy and local government policy. Strategic planning mechanisms also offer an opportunity to consider some specific issues at a larger scale in a more coordinated manner. The complexity of some biodiversity assets, and the threats facing rare and threatened species may mean that, in certain circumstances, the site-level permit system is inadequate for facilitating optimal land use or environmental outcomes. In these cases a coordinated approach, tailored to the specific problem, may achieve improved environmental outcomes. A coordinated approach may also be beneficial where there are environmentally sensitive areas, or areas with high levels of land use change. There is an opportunity to build on experience gleaned from the Melbourne Strategic Assessment, and to investigate the use of strategic approaches in appropriate areas. Improvement 1.1: Work with local government to: ensure the interoperability of local planning policies and the Victorian Government’s permitted clearing regulations, including the use of overlays develop guidance material defining the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of different parts and levels of government in relation to native vegetation policies. Improvement 1.2: Continue to investigate opportunities for using strategic planning mechanisms to deliver biodiversity outcomes from native vegetation management efficiently and effectively. Supporting reform 2: Better regulatory performance There are opportunities to improve the regulatory performance of both DSE and local government. The native vegetation regulatory system would benefit from improvements to the following areas of monitoring and reporting: enhance the use and useability of the Native Vegetation Tracking system to improve data quality and accountability consolidate and improve consistency of guidance material improve reporting of native vegetation removal and offsetting improve and broaden regulatory performance indicators so that they reflect quality, proportionality and robustness of permit assessment processes. 42 Improvement 2.1: Improve public reporting of native vegetation removal and offsetting, and improve and broaden performance indicators. Improvement 2.2: Enhance the use and useability of data systems, standard forms and guidance material. Improvement 2.3: Develop and implement more comprehensive internal quality assurance processes. Supporting reform 3: Improve offset market functionality There are opportunities to improve the functioning of the offset market, both for over-the-counter offsets and for the standard offset market. Over-the-counter offsets Over-the-counter offsets are established and registered on the Native Vegetation Credit Register. They are larger offset sites split into smaller units and sold at fixed prices. These offsets are often used to offset smaller, low impact clearing, but can be used for any scale of clearing as long as they meet the offset requirements. Over-the-counter offsets provide a mechanism for landholders to fulfil their offset obligations with reduced transaction and delay costs and predictable prices. As over-the-counter offsets pool small offsets at larger sites, they can also provide better environmental outcomes compared to multiple smaller offset sites. Currently, however, opportunities to purchase over-the-counter offsets are limited to specific locations in Victoria, and mostly provide offsets for trees. Over-thecounter offset options, for different types of clearing and offset requirements, should be readily available across Victoria. It is proposed that DSE work with local governments to establish over-the-counter offset programs and to develop standards for their functionality and integrity. Facilitating the use of Property Vegetation Plans Property Vegetation Plans were introduced to assist farmers to comply with their obligations under the permitted clearing regulations. The Plans identify areas of vegetation for removal and protection on a landholder’s property, and allow flexibility to implement the plan over time. A number of constraints, such as high upfront information costs and the need to meet prescriptive vegetation type requirements, have prevented Property Vegetation Plans being widely used. This paper outlines proposed changes to the permitted clearing regulations including the provision of improved biodiversity information, risk-based decision making and more flexible offsetting options. These changes should enable a greater set of options for many farmers to identify areas for on-farm offsetting at significantly lower cost. It is proposed that DSE work with landholders to facilitate the development and preparation of Property Vegetation Plans in line with the requirements of the new system. 43 Improve functionality of the offset market Parts of the standard offset market have a low supply of offsets. Due to a lack of competition, some offset providers have been able to charge excessively high prices. Proposed measures to improve competition in the offset market include: reduce transaction costs (see Section 0) in order to decrease barriers to market entry and improve market participation increase information availability and improve matching of buyers and sellers increase offsetting options through less restrictive offset requirements that are more outcomes focused. However, as native vegetation is highly diverse and some types are relatively scarce, in some instances it is unlikely that a well functioning market with adequate competition is achievable. For example, there may be low availability of offsets that fulfil specific species habitat requirements. In these cases, there is an opportunity for government to act as a market facilitator and to work as a conduit between buyers and sellers of offsets, enabling offset requirements to be met more efficiently. Public land considerations Whether vegetation is on land of public or private tenure should not be important when considering its biodiversity value. Nonetheless, there are a number of constraints that have limited the feasibility of taking a tenure blind approach to offsetting native vegetation removal. To date the use of public land for offsets has been limited to offsetting some small areas of clearing on public land. There is potential for a more integrated system of offsetting on public and private land, particularly where actions undertaken on public land may deliver high strategic benefits for rare or threatened species. For offsets to be established in a credible manner on public land, where and how gains in native vegetation can be achieved needs to be identified, and mechanisms are required to prevent cost shifting from occurring. It is proposed that development of an integrity framework for offsetting on public land be developed. Improvement 3.1: Work with local governments to develop over-the-counter offset provision, and expand the kinds of offsets available through these mechanisms. Improvement 3.2: Improve participation and increase efficiency in the offset market by: reducing transaction costs increasing information available improving visibility for buyers and sellers in the offset market. 44 Improvement 3.3: Identify scenarios where it is beneficial for government to play a facilitator role in the offset market. Improvement 3.4: Investigate the development of an integrity framework to guide offsetting on public land. Supporting reform 4: New approaches to compliance and enforcement The integrity and effectiveness of the permitted clearing regulations relies on the level of compliance with these regulations. Clarifying policy and improvements in processes will go some way towards putting in place the right incentives for landholders and offset providers to comply with the regulations. This would include: improving proponents’ understanding of their obligations to comply with the regulations making the permit application process simpler, more streamlined and less costly increasing options and availability of offsets through new offsetting rules and offset market reform. It is envisaged that these changes will encourage compliance with permitted clearing regulations by reducing the cost of complying with the permit system. To strengthen the system further, it is proposed that DSE work with local government to more closely monitor offset delivery, and more rigorously enforce the application of the regulations. Options for encouraging compliance include the use of technology for monitoring changes in native vegetation extent, targeting areas where compliance is low and impacts are material, and increasing information provision to raise awareness of the regulations and the importance of compliance. A new compliance and enforcement strategy will provide the community with greater assurance that native vegetation obligations are being met. Improvement 4.1: Work with local governments to develop a cost-benefit based compliance and enforcement strategy that ensures the obligations of the permitted clearing regulations are being met. Supporting reform 5: Continuous improvement program Over the ten years since adoption of Victoria’s Native Vegetation Management – A Framework for Action, DSE and local governments have undertaken a continuing program of reforms to improve the Framework’s functionality. Continuous improvements include ongoing efforts to address stakeholder concerns as they arise, addressing unintended outcomes and improving efficiencies in processes. It is important to continue to take opportunities to improve outcomes as they become 45 available. Some areas identified as requiring a particular focus in future continuous improvement activities are set out below. Interactions between state and Commonwealth regulations The Victorian Government proposes to continue to work with the Commonwealth Government to streamline the application of state and Commonwealth biodiversity regulations. This include seeking Commonwealth accreditation of Victoria’s assessment and approvals process, with the aim of reducing duplication and unnecessary red tape. Exemptions In 2006, a detailed assessment was undertaken of the exemptions from requiring a permit to remove native vegetation under the permitted clearing regulations. The proposed risk-based approach to decision making in the permitted clearing regulations will allow for greater differentiation in how clearing proposals are treated. Therefore, the requirement to have broad exemptions within the Victoria Planning Provisions may no longer be necessary in all cases. There may also be a need to amend the existing exemptions to improve certainty, clarity and operability. Following implementation of the proposed reforms to the permitted clearing regulations, DSE will undertake a review of the exemptions. Updating scientific information and tools Models will be constructed so that new and improved information can be incorporated periodically. This will include new information on species habitat, threatened status of species, and threats to biodiversity. The impact of the removal of native vegetation that is occurring, both within and outside the permitted clearing regulations, will also be monitored and incorporated into the policy settings. Refine gain scoring Gain scoring relates to the expected improvements in native vegetation through management activities. As empirical studies that measure the impact of management activities on native vegetation progress, gain scoring calculations should be updated to reflect the most up-to-date understanding of these outcomes. Monitoring of reform implementation After the reforms identified have been adopted and bedded down, their implementation will be monitored to ensure they are operating as planned and to address any unintended outcomes, or issues identified from stakeholder feedback. Improvement 5.1: Adopt a process of continuous improvement for the permitted clearing regulations, including the following actions: work with the Commonwealth Government to ensure the interoperability of state and Commonwealth regulation, and to reduce regulatory burden periodically assess exemptions 46 identify areas for investigation to improve the quality and comprehensiveness of the data that underpins the models, and update models accordingly refine gain scoring as new information on the impact of management activities becomes available assess system changes after implementation and address any emerging issues. 47 Appendix 1 – Previous reviews of Victoria’s native vegetation policy Table 1: Summary of native vegetation policy related reviews findings Review Australian Productivity Commission (2004) Impacts of Native Vegetation and Biodiversity Regulation Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (2005) Regulation and Regional Victoria: Challenges and Opportunities Review of Exemptions in Native Vegetation Provisions by Planning Advisory Committee (2006) Department of Sustainability and Environment (2008) Native Vegetation Net Gain Accounting - First Approximation Report Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (2009) A Sustainable Future Key findings relating to the permitted clearing regulation Suggested that high cost/low environmental gain outcomes be treated with more flexibility. Recognised the inefficiencies associated with the application of ‘net gain’ in vegetation at a property level. Recognised the benefits of the BushTender scheme in providing incentives to landholders to manage retained native vegetation, and offering opportunities for attaining environmental outcomes more efficiently. Raised concerns that native vegetation regulations that place more value on vegetation of a higher quality discourage landholders from maintaining the quality of vegetation on their land, and may even encourage active degradation of native vegetation. Found that ‘the complexity of regulation and its implementation posed unnecessary uncertainty on landholders’. Reported concerns regarding inconsistent interpretation and application of the native vegetation regulation by local governments and DSE. In particular relating to the ‘avoid, minimise, offset’ hierarchy, exemptions, monitoring and enforcement. Recommended simplifying and clarifying the existing regulatory framework. Identified the role of native vegetation regulations in the reduction of broadscale clearing. Raised concerns that in some cases the loss of native vegetation through exemptions may be unnecessary, and that the cumulative effect of exemptions adds to the risks for significant vegetation. Noted the importance of clear information and an integrated and consistent approach to administration of the regulations. Acknowledged the role of the clearing regulations in reducing clearing, such that the clearing of native vegetation is no longer the largest source of native vegetation change in Victoria. Noted that entitled uses of vegetation were leading to reduced levels of native vegetation quality. Supported improvement of datasets, research and reporting on native vegetation. Identified confusion regarding the NVMF’s ‘net gain’ objective and the role of permitted clearing regulations compared to government investment in achieving the objective. Reported concerns regarding inconsistent interpretation and 48 Review for Victoria: Getting Environmental Regulation Right Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission (2009) Victorian Environmental Assessment Council (2011) Remnant Native Vegetation Investigation – Final Report Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (2011) Inquiry into a Statebased reform agenda – Draft Key findings relating to the permitted clearing regulation application of regulation for the removal of native vegetation by local governments and DSE. Noted that the native vegetation permit application process is costly and time consuming. Highlighted the benefits of market-based instruments in offering significant cost savings to achieve environmental outcomes. Noted that trading rules may mean that there are few (or no) eligible offsets for a proposed clearing, increasing compliance costs to developers. Identified that the ability to remove vegetation for fire protection should be more closely aligned with the risk bushfires pose to life and property. Recognised the importance of accounting for the losses in native vegetation due to bushfire risk management. Recommended that government continue to support and expand existing programs that encourage and assist private landholders to contribute to biodiversity enhancement on private land and adjacent public land. Acknowledged Victoria’s comprehensive mapping databases and recommended continuing and expanding the collection and analysis of data on native vegetation. Suggested that a case-by-case approach to native vegetation regulation is complex and costly for local governments, DSE and landholders. Recommended a separation of responsibility for advising on native vegetation policy and for administering the controls. Reiterated concerns about how inconsistent administration of state and Commonwealth environmental regulations has contributed to uncertainty for investment. Questioned the effectiveness of the current regulatory arrangements. 49 Glossary Biodiversity – The variety of all life forms, the different plants, animals and microorganisms, the genes they contain, and the ecosystems of which they form a part. BushBroker – A program coordinated by DSE to match parties that require native vegetation offsets with third party suppliers of native vegetation offsets. BushTender – An auction-based incentive scheme to deliver native vegetation protection, habitat protection, management and improvement on private land. Clearing regulations – All regulation pertaining to clearing of native vegetation through the planning system, including permitted clearing regulation and exemptions. Delay costs – costs incurred from delay in commencing an activity. This may include foregone income from delaying increases in productivity, or lost interest if payments are delayed. Environmental weeds - A plant species that has invaded (or has the potential to invade) natural ecosystems and threaten environmental and/or conservation assets. Environmental weeds may include some Australian native plants not indigenous to a given area. Some weeds declared as noxious weeds (under schedules in the Catchment and Land Protection (CaLP) Act 1994) are also environmental weeds. Existing use rights – Landholders’ rights to continue using land in a manner that is consistent with activities that the land has been used for in the past, as set out in section 6(3) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. Gain in native vegetation – Protection and improvement in native vegetation/habitat, as measured by a site-based measure of quality and extent, achieved by active management, and/or increased security. Habitat Hectares – Combined measure of quality and extent of native vegetation. This measure is obtained by multiplying the site quality score (measured between 0 and 1) with the size of the site (in hectares). Habitat Hectares Assessment (Vegetation Quality Assessment) – A site-based measure of quality of native vegetation that is assessed in the context of the relevant native vegetation type, compared to its pre-1750 condition. Incorporated document – A document that is included in the list of incorporated documents in a planning scheme. These documents effect the operation of the planning scheme. Landholder – An owner, occupier, proprietor or holder of land. 50 Landscape context – Measure of the viability and functionality of a patch of native vegetation in relation both to its size and position in the landscape, and to surrounding vegetation. Local planning scheme – Policies and provisions for use, development, and protection of land in a local government area. Loss in native vegetation – Decreases in native vegetation, as measured by a sitebased measure of quality and extent. Melbourne Strategic Assessment – Agreement between the Victorian and Commonwealth Governments that defines areas where clearing can occur within Melbourne’s Urban Growth Boundary 2010. It includes the corresponding conservation measures that must be undertaken to meet Victorian and Commonwealth laws. Negative externality – Occurs when a party undertaking an action does not have to pay the full cost of their actions. The additional cost is borne by other parties. Native vegetation – The Victoria Planning Provisions defines native vegetation as plants that are indigenous to Victoria, including trees, shrubs, herbs and grasses. The permitted clearing regulations consider native vegetation as vegetation that is indigenous to a site. Native vegetation credits – Gains in the quality and/or extent of native vegetation that are subject to a secure and ongoing agreement registered on the land title, or by transferring land to a more secure tenure type. Native Vegetation Credit Register – A DSE administered statewide register of native vegetation credits that meet minimum standards for security and management of sites. It records those that can be traded, and those that have been used to meet a specific offset requirement. Native vegetation extent – Area of land covered by native vegetation. Native Vegetation Particular Provision – Clause 52.17 in the Victoria Planning Provisions that relates to the removal, destruction or lopping of native vegetation. Native vegetation policy – All Victorian policy relating to native vegetation including permitted clearing, exemptions, regulation of uses, government investment and management of public land. Native vegetation quality – A site-based measure of vegetation condition that is assessed in the context of the relevant native vegetation type, compared to its pre-1750 condition, as determined by a Habitat Hectare assessment. 51 Native vegetation regulation – All Victorian regulations related to native vegetation including permitted clearing, exemptions and duty of care. Native Vegetation Tracking System – A web-based information system used by DSE for recording details of planning permits assessed by the Department, including the location and amount of native vegetation clearing and offset requirements. Offset – Measurable native vegetation conservation outcomes resulting from any works, or other actions to make reparation for the loss of native vegetation arising from the removal or destruction of native vegetation. Offset market – A system which facilitates trade between parties requiring offsets and third party suppliers of offsets. Option value – The value from preserving an environmental attribute on the basis that it may have potential use, or provide benefits in the future that are not fully understood now. Particular Provisions – provisions in the Victoria Planning Provisions that relate to specific activities (for example, native vegetation removal has a Particular Provision). Permit – a planning permit to remove native vegetation. Permitted clearing – clearing that a permit to remove native vegetation has been granted for. Permitted clearing regulations – the rules in the planning system that regulate permits for the removal of native vegetation. Peri urban – areas of land fringing urban areas that are not fully urban or rural. Planning provisions – see Victoria Planning Provisions. Planning scheme amendment – Change to a planning scheme. There is an official process that must be followed to amend a planning scheme. Private land – land that is privately owned. For the purposes of this document this does not include freehold land that is owned by government departments or authorities. Public good – A good that no-one can be excluded from using, where one party’s use does not diminish the benefit that other parties obtain from using the good. Public land – For the purposes of this document, public land refers to land that is held by government departments or authorities for the benefit of the people of 52 Victoria. This includes State forest, national parks, Crown land and other reserves, such as roadsides. Rare or threatened species – A species that is listed in: DSE’s Advisory List of Rare or Threatened Plants in Victoria as ‘endangered’, ‘vulnerable’, or ‘rare’ DSE’s Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria as ‘critically endangered’, ‘endangered’ or ‘vulnerable’ DSE’s Advisory List of Threatened Invertebrate Fauna in Victoria as ‘critically endangered’, ‘endangered’ or ‘vulnerable’. Remnant patch of native vegetation – Either: an area of native vegetation, with or without trees, where at least 25 per cent of the total understorey plant cover is native plants, or an area with trees where the tree canopy cover is at least 20 per cent. Site – An area of land within a single parcel that contains contiguous patches of native vegetation. Species persistence – The continued existence and diversity of a species into the future. Factors that contribute to a species’ potential to persist include population, habitat and genetic diversity within a species. Strategic planning – a coordinated approach to planning where areas for conservation and areas which can be cleared are strategically identified. Victoria Planning Provisions – a comprehensive list of planning provisions that provides a standard template for individual planning schemes. These provisions outline statewide obligations that are enacted through the permit process. For more information call the Customer Service Centre 136 186 twitter.com/DSE_Vic youtube.com/DSEVictoria flickr.com/DSEVictoria http://www.dse.vic.gov.au/ 53