Report - New Maps - University of Kentucky

advertisement

Documenting and Digitalizing Health Inspection Scores of the Restaurants of

Lexington, KY: a collaborative project between University of Kentucky

Geography/GIS students and OpenLexington, a local organization advocating open

and transparent government data.

University of Kentucky students:

Dylan Powell (dy.pow311@gmail.com)

Preston Evans (evans.preston@gmail.com)

OpenLexington:

Chase Southard (chase.southard@gmail.com)

Chris Stieha (stieha@hotmail.com)

www.openlexington.org

Table of Contents

•

Project Summary

•

Needs Assessment Report

•

Progress Report

•

Data Dictionary

•

Final Maps

•

Conclusions

Project Summary

In collaborating with the local government data transparency group, OpenLexington, we

hoped to collect a fairly comprehensive catalogue of most of Lexington’s restaurants, their

corresponding health inspection scores, and additional data that would allow us to critically

analyze the collection and inspection methods of the Fayette County Health Department. Using

‘smartphones’ and free website available to the public, we wanted to collect, organize, and

display this health inspection data in interesting and informative ways, and show that the current

methods the Fayette County Health Department uses to collect their health inspections could be

updated to more modern electronic methods with many more practical applications. Finally, we

wanted to release our collected and polished data to the public free-of-charge, in an effort to

show the many purposes ‘open data’ can serve.

Beginning with the initial data collection, we produced a template for a ‘smartphone’based health inspection form that focused on the name, address, latest health inspection score,

and key health violations for Lexington restaurants, along with the corresponding comments for

the individual violations. The data was gathered by the students of UKC101, an introductory

course in digital mapping at the University of Kentucky taught by Dr. Matthew Wilson. Once

the data was compiled, we worked to organize and standardize the data so it was usable by our

mapping software, and in the process, came to better understand the advantages and

disadvantages of technology-based primary data collection. Once the dataset was organized in a

uniform format, we used a combination of GIS software (ArcGIS by Esri) and free web-based

mapping applications (Geocommons by GeoIQ) to display the data in different ways, seeking to

find patterns between the scores, types of food served, average household income, and many

other factors.

Needs Assessment Report

1. Project Background Information

OpenLexington is a non-profit group, based in Lexington, which facilitates means of data

collection and organization outside of governmental control and taxation. Created in 2010 by

Chase Southard, Chris Stieha, and other like-minded individuals, their goal is to make such data

open to the public for use in developing applications and software that can then be freely

distributed to the average interested citizen. They have already worked together with local

government and citizen groups to broaden the amount of ‘open data’ in Lexington, and have

long-term goals of working with government departments and employees to both streamline data

collection and make the data open to general users. This data will eventually be presented to a

group of Lexington government officials, local GIS workers, and interested citizens at CityCamp

Lexington, an ‘unconference’ seeking to assess and find solutions for the large amounts of local

data that are still not readily available to the public.

2. Goals and Objectives

In the most general terms, our project will be looking at the topic of closed-data

collection practices in local government, and how best to work with the agencies to make the

data open to the public for use and easier to organize through digitalization of the data collection

process. In the case of our biggest project this semester, we will be helping OpenLexington

develop an application for Smartphones that allows users to easily browse the health inspection

scores and violation numbers of local restaurants in the Lexington area. The application will be

open source and free to anyone interested.

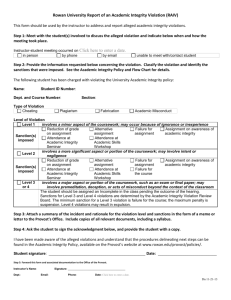

This process starts with the collection of data via the application and website EpiCollect,

which we have used to create a data collection form that fits our needs and provides the

necessary fields for data entry. The form is designed by dragging and dropping entry fields that

can have either binary or multiple values, and labeling the entry fields as needed. We designed

the form to follow the format of an actual Fayette County Health Inspection form, with entry

fields for the names, addresses, scores, and violations of individual restaurants, and extra fields

provided for the comments associated with each violation. We realized that having an entry field

for every possible violation would be excessive and hard to maintain, so we chose the ‘key’

violations, which are those that require a follow-up inspection within a set amount of time to

make sure the violation has be fixed. After canvassing the restaurants of Lexington, the

collected data will be organized and polished into a user-friendly format, using Microsoft Excel

to produce a spreadsheet of the data. Finally, we will use GIS software to spatially represent this

data as clearly as possible, and the finished application and spatial data may be presented to the

local Health Department as an alternative to their current pen-and-paper methods of inspections.

3. Data Acquisition and Preparation Steps

All the data we will be collecting for the application will come from the primary source,

the posted inspections that are required to be visible to the public inside every restaurant. To

keep the data streamlined and avoid clutter, we will be gathering the names, addresses, type of

food served, most-recent health inspection scores, and violation types of the restaurants we visit.

The canvassing will be done in phases by small groups of students using the EpiCollect form we

have created, and the data will be immediately available to work with as soon as it is uploaded

from the EpiCollect Smartphone application. Once all the data is collected, we can import it into

Microsoft Excel, and then format it to be usable by ArcGIS.

4. List of Maps and Analyses

Our biggest task in the project will be the collection and organization of all the data we

acquire, as we hope to have many, if not most, of Lexington's restaurants catalogued with data

we can then use in ArcGIS. The categories of data that we will collect using the EpiCollect form

we created are the restaurant name, address, zip code and a list of the major violations. By the

end of the project, we will have used ArcGIS to create an interactive map that can display the

collected restaurant data with the ease of a click, and we hope to work with OpenLexington to

turn this kind of map into an application that could be used on-the-go with ‘smartphones’. This

is the eventual product that could be shown to the Health Department as a technological

alternative to their traditional paper health inspection forms.

5. Steps Required

A) Create the necessary EpiCollect form for review by OpenLexington (Preston)

B) Write the Needs Assessment Report (Dylan)

C) Organization of student groups for canvassing (Dylan)

D) Monitor data collection as it is happening to ensure quality data (Preston)

E) Create a Progress Report to show what has been done (Preston/Dylan)

F) Wrap-up data collection

G) Format all collected data in Excel for use with ArcGIS (Preston/Dylan)

H) Use ArcGIS to produce a map that represents our data (Preston/Dylan)

PROGRESS REPORT

Completed Parts of Project:

•

Needs and goals of community partners determined.

•

Set up an EpiCollect form for data collection.

•

Divide student volunteers into groups for data collection.

•

Data collected and submitted through EpiCollect server.

•

Data aggregated into an Excel spreadsheet.

•

Problems Preventing Completion

•

Missing data fields on spreadsheet.

•

Incorrect dates of last inspection.

•

Geocode data with missing latitude/longitude coordinates.

MID-PROJECT MEETING

During the mid-project meeting, we met with Chase Southard and Chris Stieha and discussed the

current state of the project. We talked about our original goals with the project, and made sure

everyone was still thinking along the same lines. We agreed that the primary goal was to get the

collected data completely organized so that we could start importing it into ArcGIS and creating

maps, and also so we could put it on the internet and truly make it ‘open data’. We also talked

about interesting visual and spatial representations we could use to display the data, and assessed

whether these goals were manageable.

CHANGES TO PROJECT GOALS

After the mid-project meeting, we didn’t make any large changes to our original goals of creating

a refined and polished dataset, and representing the data in interesting ways that could be

possibly used to convince others of the value of ‘open data’.

Data Dictionary

3/6/12---Cleaned up addresses, corrected capitalization, made street format uniform (Dylan)

3/6/12---Corrected false addresses using Google Maps, filled in info for missing addresses (Dylan)

3/8/12---Formatted dates as much as I could (multiple cases of clearly wrong dates (4/7/4725) and

missing data (3/ /2012)). We’ll need to follow up on these. (Dylan) (Dr. Wilson thinks it may be that they

simply entered the date in the wrong order, and Excel can’t recognize it, since it was a simple text input

box on the EpiCollect form. We can email TA’s for specific student groups, since they should all have

hand-written notes)

3/20/12---Corrected names of restaurants and general misspellings (Dylan)

3/22/12--- Cleaned up the violations. Added N/A to entries that were not selected. Changed Null values to

no plus the violation number- (Preston)

3/27/12--- Cleaned up the violations. Added N/A to entries that were not selected. Changed Null values to

no plus the violation number, Cleaned up type of restaurant column, Cleaned up the rest of the dates, Put

N/A on dates that I could not discern from the photo or where the photo did not exist.

4/2/12--- Simplified the types of restaurants into bigger categories to allow easier filtering and

symbolizing, changed violation assertations from “Yes01” format to “yes” format. This allows easier use

with Geocommons, and less confusion in the data. (Dylan)

KEY TERMS AND VIOLATIONS FOR DATASET

-latitude/longitude/altitude= The respective spatial data for the restaurant.

-photo= Link to the photo of the health inspection form of the associated restaurant (some links are dead).

-Name/Address/Zip/City/State= Name of the restaurant and its address in Lexington, KY.

-Score/Date= The health inspection score the restaurant received and the date that it was last inspected.

-Type/Sub-Type= The general type of food served at the restaurant, and a more specific description of the

food if applicable/available.

-Vio##/Vio##Desc= The key violations we analyzed (‘yes’ if violated, ‘no’ if not), and the description of

the specific violation at the restaurant.

-Ageofformdays= The number of days that has passed since the restaurant received its last health

inspection.

Sample Fayette County Health Inspection on next page.

-Critical Violations (the ones we collected data for) are listed in bold text. These include:

Violation 1: SOURCE, CONDITION, NO SPOILAGE

Violation 3: POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS FOOD – SAFE TEMPERATURE

Violation 4: FACILITIES TO MAINTAIN PRODUCT TEMPERATURE

Violation 7: POTENTIALLY HAZARDOUS FOOD NOT RE-SERVED

Violation 11: PERSONNEL WITH INFECTIONS RESTRICTED

Violation 12: HANDS WASHED AND CLEAN, HYGIENIC PRACTICES

Violation 20: SANITIZATION RINSE CLEAN, EQUIPMENT AND UTENSILS SANITIZED

Violation 27: WATER SOURCE, SAFE, HOT AND COLD UNDER PRESSURE

Violation 28: SEWAGE AND WASTE DISPOSAL

Violation 30: CROSS CONNECTION, BACK SIPHONAGE, BACKFLOW OF PLUMBING

Violation 31: NUMBER AND ACCESSIBILITY OF TOILET AND HANDWASHING FACILITIES

Violation 35: INSECTS/RODENTS, OUTER OPENINGS PROTECTED, NO ANIMALS (BIRDS/TURTLES)

Violation 41: TOXIC ITEMS PROPERLY STORED, LABELED, USED

-The corresponding number of points the violation is worth can be found to the right of the violation

itself.

-The overall score is listed in red or green in large print on the form, green implying an acceptable score,

and red indicating multiple critical violations.

-In order to provide open access to the EpiCollect form we created, the direct link

http://epicollectserver.appspot.com/project.html?name=LexHealthProject will take you to the EpiCollect

page for our form, then login using openlexingtonproject@gmail.com as the username, and ge0graphy

(with a zero instead of an “O”) as the password.

-Finally, the dataset has been uploaded to www.geocommons.com, where it can be found by searching for

“LexHealthScores” or using key search terms such as Lexington/health/inspection/scores.

-Direct link to Geocommons map of data: http://geocommons.com/maps/161675#

-The map is open for editing to the public, and can be filtered by any combination of desired filters (e.g.

Type, Score, Name, Address, Violation)

-A few of our maps utilize a visualization tool called ‘kriging’. These maps use this technique to

interpolate values of certain characteristics (in our maps, inspection score and date of last inspection) for

unknown locations, based on the values of known locations.

OUTPUTS

The following images are the maps we have produced using the dataset we collected.

The titles indicate the values that are being compared in the map, and legends and scales for each

map have been provided.

We have also created an online map using the dataset through Geocommons, a free webbased mapping tool and database for spatial data. The map is open to editing, but can also be

embedded on a website by using the following embed code:

<style>#geocommons_map_161675 {width: 100%; height: 400px; position:relative;}</style>

<div class="geocommons_map" id="geocommons_map_161675"></div><br/>

<a class="geocommons_map_link" id="geocommons_map_161675_link"

href="http://geocommons.com/maps/161675">View map on GeoCommons</a>

<script type="text/javascript" charset="utf-8"

src="http://geocommons.com/javascripts/f1.api.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" charset="utf-8">

var geocommons_map_161675 = new F1.Maker.Map({map_id: "161675", dom_id:

"geocommons_map_161675"});

</script>

Conclusion

Through the process of completing a GIS-based project, from the primary data collection

to the final maps created using the data we acquired, we have learned many things about the

advantages and disadvantages of electronic primary data collection, and in specific regard to our

data, about the spatial and temporal patterns of local health inspections of restaurants in

Lexington, Kentucky. In terms of electronic primary data collection, we have learned that data

which has traditionally been collected and filed non-electronically can often be collected and

made readily available to the public with greater ease if it collected using some type of electronic

form. Not only are these forms fairly simple to produce, but they also have the potential to be

altered for specific purposes and uses, unlike paper copies. When the data has been collected

and entered onto the form, it can be immediately uploaded to a server that can collect and

organize the data automatically, and then store the data on a public server that can be accessed by

anyone with a computer and internet connection. This makes the data more available for use to

not only the government employees in the department that the data concerns, but also to

interested local citizens who can use the data, either in computer or phone applications or various

visual representations for their own purposes. In its current non-electronic form, the same data

must be acquired through the department that collected the data using pen-and-paper methods,

and often is found in a very rudimentary and inflexible data format that cannot be readily used by

either employees or citizens. In addition, the data is only ‘easily’ available to those who can

physically go to the department, which is often in Frankfurt, Kentucky, making it very difficult

for those who don’t live relatively close or lack sufficient transportation.

One of our biggest goals with this project is to show how 'open data' can empower

average citizens to be able to create useful and interesting things, simply by giving citizens easily

available access to datasets like ours. By making maps with our data, we were able to find many

interesting patterns in Lexington's restaurants and neighborhoods. We compared aspects such as

average household income of a census tract, types of restaurant most prevalent in an area,

densities of restaurants and their associated scores, and many other factors. Using the free webbased tool Geocommons, we were able to upload our dataset to the internet and create a userfriendly, interactive map that allows average people to filter the restaurants of Lexington by

many different factors, such as score, individual violations, and even by how much time has

elapsed since the restaurants last inspection. Finally, we presented all of our methodology, data,

and outputs to interested citizens and government workers at CityCamp Lexington, a local

'unconference' to encourage making Lexington government data more readily available to people

who can use the data in software for the benefit of the public.