File

advertisement

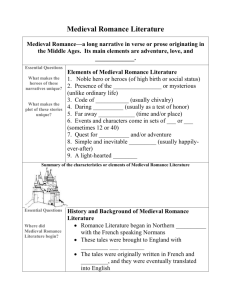

Romance

ROMANCE, MEDIEVAL (also called a chivalric romance): In medieval use, romance referred to

episodic French and German poetry dealing with chivalry and the adventures of knights in warfare as they

rescue fair maidens and confront supernatural challenges. The medieval metrical romances resembled the

earlier chansons de gestes and epics. However, unlike the Greek and Roman epics, medieval romances

represent not a heroic age of tribal wars, but a courtly or chivalric period of history involving highly

developed manners and civility, as M. H. Abrams notes. Their standard plot involves a single knight seeking

to win a scornful lady's favor by undertaking a dangerous quest. Along the way, this knight encounters

mysterious hermits, confronts evil blackguards and brigands, slays monsters and dragons, competes

anonymously in tournaments, and suffers from wounds, starvation, deprivation, and exposure in the

wilderness. He may incidentally save a few extra villages and pretty maidens along the way before finishing his

primary task. (This is why scholars say romances are episodic--the plot can be stretched or contracted so the

author can insert or remove any number of small, short adventures along the hero's way to the larger quest.)

Medieval romances often focus on the supernatural. In the classical epic, supernatural events originate in the

will and actions of the gods. However, in secular medieval romance, the supernatural originates in magic,

spells, enchantments, and fairy trickery. Divine miracles are less frequent, but are always Christian in origin

when they do occur, involving relics and angelic visitations. A secondary concern is courtly love and the

proprieties of aristocratic courtship--especially the consequences of arranged marriage and adultery

A large number of such romances survive due to their enormous popularity, including the works of Chrétien

de Troyes (c. 1190), Hartmann von Aue (c. 1203), Gottfried von Strassburg (c. 1210), and Wolfram von

Eschenbach (c. 1210). England produced its own romances in the fourteenth century, including the Lay of

Havelok the Dane and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. In 1485, Caxton printed the lengthy romance Le Morte

D'Arthur, a prose work that constituted a grand synthesis of Arthurian legends. Gradually, the poetic genre

of medieval romance was superseded by prose works of Renaissance romance

{From K. Wheeler, “Literary Terms”}

Medieval romances are narrative fictions representing the adventures and values of the

aristocracy. Romances may be written in prose, in which case they tend to resemble "histories," with more

pretense to being truthful about the past, or they may be written in stanzaic of non-stanzaic verse, in which

case the narrators rarely make more than perfunctory efforts to simulate historicity. Characters nearly always

are, or are revealed to be, knights, ladies, kings, queens, and other assorted nobles. Plots often involve

conflicts between feudal allegiances, pursuit of quests (by males) and endurance of ordeals (by females), and

the progress or failure of love relationships, often adulterous or among unmarried members of the

court. Romances typically stress the protagonists' character development over any minor characters, and

nearly all seem like "type characters" to modern readers used to full psychological realism. Marvels, especially

the supernatural, routinely occur in romance plots, whereas they are viewed with skepticism in histories,

though they also are positively necessary to saint's lives, a narrative form which resembles both histories and

romance. "Romance" is not a synonym for social behaviors leading to sexual behavior or marriage (a Mod.E.

appropriation of one aspect of the genre). "Romantic" is a term almost never used in Medieval. Romance is

an ancestor of the novel.

{From Arnie Sanders, Goucher College}

Picaresque

The pícaros, upon whom the picaresque novel is based, were usually errand boys, porters, or factotums

(persons employed to do a wide variety of tasks) and were pictured as crafty, sly, tattered, hungry,

unscrupulous, petty thieves. They stole to escape starvation and were likable despite their defects.

The picaresque novel, a reaction against the absurd unrealities and idealism of the pastoral, sentimental, and

chivalric novels, represents the beginnings of modern Realism. It juxtaposed the basic drives of hunger

cruelty, and mistrust and the honorable, glorious, idyllic life of knights and shepherds. Hunger replaced love

as a theme, and poverty replaced wealth.

Early picaresque novels were both idealistic and realistic, tragic and comic, and the authors attacked political,

religious, and military matters. Some authors were sincere reformers, while others conveniently set off their

sermons so they might be easily avoided. They reflected the poverty and and unsound economic conditions

of late sixteenth century Spain. Spaniards were living in a dream world after the glories of the conquest of the

New World. They flocked to the cities, the upper classes refusing to work with their hands, cultivate the land

or engage in business or commerce, all of which were viewed as degrading. Poor knights starved with the

beggars. Thus, comic elements are omnipresent, the sentiment is tragic -the tragedy of a Spain that was

outwardly the most powerful nation in the world but inwardly on the path to decline and ruin. The picaresque

genre faithfully portrays these tragic conditions.

Usually the pícaro is of the lower classes. Forced into a life of servitude by the severity of the times, he drifts

into a life of petty crime and deceitfulness in his struggle for survival. The tone of the novel is hard, cynical,

skeptical, often bitter, and it often portrays the corrupt and ugly. Humor abounds, but it is only a step

removed from tears, and what appears to be funny is tragic in a different light.

In its emphasis on the seamier side of life, the picaresque novel twists and deforms reality. The pícaro lives by

his wits and steals and lies just to stay alive. His many employers give the narrator the opportunity to satirize

various social classes and to paint a portrait of a period full of living, brawling human beings.

[Extracted from: Chandler, Richard E & Kessel Schwartz, A New History of Spanish Literature, (Baton Rouge:

LSU Press, 1991), pp. 118-20.]

PICARESQUE NOVEL (from Spanish picaro, a rogue or thief; also called the picaresque narrative and

the Räuberroman in German): A humorous novel in which the plot consists of a young knave's

misadventures and escapades narrated in comic or satiric scenes. This roguish protagonist--called a picaro-makes his (or sometimes her) way through cunning and trickery rather than through virtue or industry. The

picaro frequently travels from place to place engaging in a variety of jobs for several masters and getting into

mischief. The picaresque novel is usually episodic in nature and realistic in its presentation of the seamier

aspects of society.

The genre first emerged in 1553 in the anonymous Spanish work Lazarillo de Tormes, and later Spanish

authors like Mateo Aleman and Fracisco Quevedo produced other similar works. The first English specimen

was Thomas Nashe's The Unfortunate Traveller (1594). Probably the most famous example of the genre is

French: Le Sage's Gil Blas (1715), which ensured the genre's continuing influence on literature. Other examples

include Defoe's Moll Flanders, Henry Fielding's Jonathan Wild, Smollett's Roderick Random, Thomas Mann's

unfinished Felix Krull, and Saul Bellow's The Adventures of Augie March. The genre has also heavily influenced

episodic humorous novels as diverse as Cervantes' Don Quixote and Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

{From K. Wheeler, “Literary Terms”}