March 2013

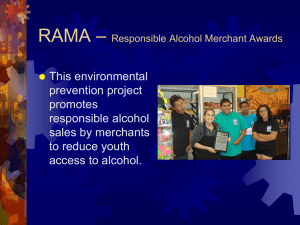

advertisement