HERE - Step Short

advertisement

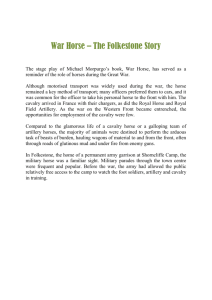

Introductory Notes, Suggestions and Resources for Folkestone in WW1 KEY: FOLKESTONE’S UNIQUE WW1 HISTORY BROUGHT TO LIFE Metropole & Grand: WAACs, War Poets and Belgian Refugees Site of Rest Camp No 3. How did the soldiers spend their last few hours on English soil before setting off for the Western Front? Manor House Hospital. WW1 medicine Nursing, equipment. Dorothy Earnshaw and her Friendship Album. Hospital Ships Wartime Folkestone. Recruiting, White Feathers Air Raids, Troopships, Peace & Remembrance Bandstand. WW1 music and entertainment. © Google maps © Michael George 2013 The Leas The Metropole and The Grand were both good class hotels before WW1, where well-to-do Edwardians enjoyed every level of luxury, and from where they could promenade along the famous Leas. Backgound: When war broke out on August 4th 1914, Folkestone was transformed from popular seaside resort into a frontline town. It became a massive army camp, where troops trained and waited for their turn to board the Troop Ships at the harbour to take them to Boulogne, then onward to Western Front. For many, their stay in Folkestone was the last time they set foot on English soil. A whole support system was created in Folkestone to meet the needs of the soldiers: entertainment and recreation, Religion, medical services, food and rest, training and education. As well as British, Empire and Allied soldiers heading to the Front, other visitors arrived in Folkestone. Thousands of Belgian regugees, Chinese workers, wounded and ‘leave’ troops. The single most useful source of information about Folkestone during WW1 is the book, Folkestone during the War, 1914-1919, by Reverend J C Carlile. Luckily it can be found online.It can be searched and downloaded. There are several refences to The Leas, the Metropole, the WAACs and the Belgian refugees. To find the book go to: http://archive.org/details/folkestoneduring00carliala The Step Short website also has many images and other material that will be useful. www.stepshort.co.uk The 2008 book, Dover and Folkestone during the Great War by Michael & Christine George is also a useful introduction. Much of this book can be read online at: Google books The War Poets We have chosen this topic at The Metropole because Wilfred Owen stayed there. The hotel was used as accommodation for officers and must have provided such a contrast to the living conditions experienced in the Trenches. In a letter to his mother, Owen described this contrast. The team will need to research the War Poets, find any links to Folkestone and decide how best to portray this subject. Recitals are likely to to be a key activity. Is there any novel way of presenting the poetry? Other poets and authors with a Folkestone WW1 connection: Vera Brittain Siegried Sassoon John Macrae Private George Willis Rupert Brooke Private Charles Davis JRR Tolkien Charles Hamilton Sorley Henry Williamson Charles Blackall The WAACs and QMAAC The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps was formed to enable women to take over some of the jobs done by soldiers so as to free the men to move into the front lines to replace those killed or injured. The WAACs were trained as drivers and mechanics, as well as clerks, cooks and support roles. Nearly 50,000 women were recruited. Most remained in the UK, but 7000 were trained for service in France and Belgium alongside the British Expeditionary Force. It was these women who came to Folkestone. WAACS renamed Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps in 1918. In 1917 the officers, for whom the Hotel Metropole had been a pleasant billet en route to the front, had to find other accommodation. The building was taken over by the WAACs. There was a permanent staff of some 20 women and they took care of the training and preparations for those who were chosen for overseas service. The arrival of the WAACs in Folkestone provided a welcome diversion for the thousands of soldiers in the town, though the women were very strictly controlled in their social lives. © OU Digital Archive With heavy losses on the Western Front in 1916, the British Army became concerned by its reduced number of fighting soldiers. Lieutenant General Sir Henry Lawson suggested to Brigadier General Auckland Geddes, Director of Recruitment at the War Office, that far too many men were doing what he called "soft jobs". After talks with the government it was decided to use women to replace men doing certain administrative jobs in Britain and France. These men could then be sent to fight at the front. In January 1917, the government announced the establishment of a new voluntary service, the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC). The plan was for these women to serve as clerks, telephonists, waitresses, cooks, and as instructors in the use of gas masks. It was decided that women would not be allowed to hold commissions and so that those in charge were given the ranks of controller and administrator. Helen Gwynne-Vaughan was chosen for the important job as the WAAC's Chief Controller (Overseas). The WAAC uniform consisted of a small, tight-fitting khaki cap, khaki jackets and skirts. Regulations stated that the skirt had to be no more than twelve inches above the ground. To maintain a high standard of fitness, all members of the WAAC had to do physical exercises every day. This included Morris dancing and hockey. Women in the WAAC were not given full military status. The women enrolled rather than enlisted and were punished for breaches of discipline by civil rather than military courts. Women in the WAAC were divided into officials (officers), forewomen (sergeant), assistant forewomen (corporals) and workers (privates). Between January 1917 and the Armistice over 57,000 women served in the WAAC. Newspapers in Britain began publishing stories claiming that the WAAC in France were becoming too friendly with the soldiers and large numbers were being sent home because they were pregnant. A senior member of the WAAC, Miss Tennyson Jesse, was asked to carry out an official investigation into these stories. In her report, Tennyson Jesse pointed out that between March 1917 to February 1918, of the 6,000 WAACs in France, only 21 became pregnant. Tennyson Jesse argued that this was a lower-rate than in most British villages. Tennyson Jesse proudly pointed out that of all the women serving in France only 37 had been sent home for incompetence or lack of discipline. Although not on combat duties, members of the WAAC had to endure shelling from heavy artillery and bombing raids by German aircraft. During one attack in April, 1918, nine WAACs were killed at the Etaples Army Camp. British newspapers claimed that it was another example of a German atrocity but Helen Gwynne-Vaughan was quick to point out at a press conference that as the WAAC were in France as replacements for soldiers, the enemy was quite entitled to try and kill them. © IWM The above picture is a powerful portrayal of how the WAACs saw themselves. With military style discipline and ranks, they aspired to soldierhood. The picture on the left must have raised some eyebrows: cricket was the quintessentially male dominated sport. Keeping fit was also encouraged, but only with chaperons standing guard!! Your Research - suggestions If searching online for information, be sure that you are reading about British WAAC and QMAAC women during the First World War. WAACs or WACs again became a feature of both the British and American forces during the Second World War. The National Army Museum website is a good place to start your research. It describes the system of hierachy (ranks) and duties. Below is a screenshot of one page: © Michael George, Step Short, 2013