III-F Wildland Urban Fire - Coast Colleges Home Page

advertisement

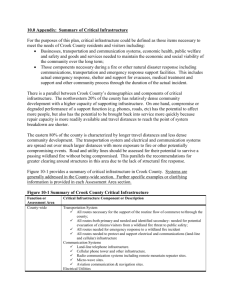

Part III-F – Wildland/Urban Fire A. OVERVIEW.............................................................................................................. 2 B. CALIFORNIA FIRE VULNERABILITY ............................................................................ 2 CALIFORNIA FIRE HISTORY ............................................................................................... 3 Figure 1 - Annual Acres Burned by Decade and Life Form, 1950-2000s ........................................................3 Figure 2 - Fire Frequency (Number of Times Burned), 1950 – 2008 ...............................................................4 WILDLAND FIRE VS. WILDLAND-URBAN INTERFACE FIRES.................................................. 5 RULE-MAKING AUTHORITY AND FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY IN CALIFORNIA ....................... 5 URBAN FIRE CONFLAGRATION POTENTIAL ........................................................................ 5 Table 1 - Fire History by Number of Structures Destroyed .............................................................................8 Figure 3 - State of California Fire Threat .........................................................................................................9 Figure 4 - State and Federal Declared Fire Disasters from 1950 to 2009 .....................................................10 Figure 5 - Number of structures ignited in California 2000 to 2009................................................................11 Figure 6 - Wildfire Hazard Ranking in Local Hazard Mitigation Plans............................................................12 CALIFORNIA STRATEGIC FIRE PLAN ................................................................................ 13 C. ORANGE COUNTY ................................................................................................. 14 Figure 7 – Orange County Wildland Fire Management Planning Areas ........................................................14 WILDLAND URBAN INTERFACE ........................................................................................ 15 WILDLAND FIRES ........................................................................................................... 16 Figure 8 - Current fuel hazard ranking as of 2005 for Orange County. ..........................................................16 Figure 9 – Orange County Vegetation ...........................................................................................................19 WILDLAND FIRES AS A THREAT TO SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ............................................. 20 THE INTERFACE ............................................................................................................. 21 THE THREAT OF URBAN CONFLAGRATION ....................................................................... 23 FIRE FOLLOWING EARTHQUAKE...................................................................................... 23 FIRE CODES .................................................................................................................. 24 D. COAST COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICT ................................................................. 28 Table 2 - CCCD Sites located in OC Wildland and Urban Fire Planning Areas ............................................28 CCCD’S WILDLAND AND URBAN FIRE THREAT ................................................................ 29 E. URBAN/WILDLAND FIRE HAZARD MITIGATION STRATEGIES ..................................... 30 Part III-F Urban Fire A. OVERVIEW This section of the plan will look at the fire threat to CCCD, its service area and facilities. There are three basic types of fire hazards: Wildfire Wildland-urban interface Urban fire Part B of this section will review the overall fire threat to California followed by Part C which will discuss the fire threat to the Orange County area. Fires can also be caused as secondary hazards following major earthquakes. Earthquakes were identified earlier in this plan as major hazards to the CCCD. This plan will discuss fire and earthquake in Part C. Part D explains the fire threat to the CCCD, its service area and its facilities. Part E outlines the fire mitigation strategies needed by the CCCD to prevent and prepare for major fire incidents. California and Orange County have an extensive history of every type of fire (wildfires, wildlandurban interface and urban). Over the past 10 years, Southern California has been hit by three catastrophic fires. Because of this, the state, its 57 counties and cities have developed and updated a series of comprehensive building codes, fire codes, hazardous materials regulations, fire prevention programs and educational programs. They also reviewed and updated quality emergency response equipment and ensured that highly trained and technical first responders are prepared to respond to all types of fires in California. Educational facilities are of particular concern to fire prevention professionals. Over the past 60 years, knowledge, experience and unfortunately tragedy have taught us the importance of fire prevention. The California Fire Marshal’s Office and fire professionals have developed fire codes to ensure limited fires in public schools including the community colleges. Although sometimes bothersome and expensive, these codes ensure the safety of California’s children. B. C ALIFORNIA FIRE VULNERABILITY Among California’s primary hazards, fires (including wildfire, wildland-urban interface and urban fire) represent the third most destructive source of hazard, vulnerability and risk, both in terms of recent state history and the probability of future destruction. According to the 2009 California State Hazard Mitigation Plan, California is recognized as one of the most fire-prone and consequently fire-adapted landscapes in the world. The combination of complex terrain, Mediterranean climate, and productive natural plant communities, along with ample natural and aboriginal ignition sources, has created a land forged in fire. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 2 of 31 CALIFORNIA FIRE HISTORY Excluding fires occurring in the desert, estimates of annual acreage burned prior to the arrival of European settlers range between 4.5 and 12 million acres annually. These findings indicate that dramatic influence of natural wildfire, which supports and maintains ecosystem structure and function in California’s wildlands. Dramatic changes in fire activity accompanied the European settlement of California, partly due to agriculture, grazing, logging and mining. These changes were magnified through land use practices (agriculture, urbanization) that removed natural fuel. After the turn of the 20th century, these land uses were organized around fire suppression designed to protect people and property. From 1950 to 2008, an average of 320,000 acres burned annually in California. However, there is substantial annual variability, attributable to weather conditions and large lightning events that result in many dispersed ignitions in remote locations. Annual totals range from 31,000 acres in 1963 to a high of 1.37 million acres in 2008. Looking at acreage burned by decade and life form confirms these basic trends. Fire is most common in scrublands across all decades, with a large spike in the first decade of the 2000s. Figure 1 - Annual Acres Burned by Decade and Life Form, 1950-2000s III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 3 of 31 Figure 2 - Fire Frequency (Number of Times Burned), 1950 – 2008 This map shows the distribution of burn frequency from 1950 to 2008. The South Coast and Central Coast regions show the highest frequencies. Orange County is located in the South Coast region. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 4 of 31 The California State Hazard Mitigation Plan research proves the following trends exist in California: Increased fire severity Increased human infrastructure at risk Increased hazards and risks associated with vegetation fires due to climate change Fire suppression costs are increasing Increased losses from fires These studies together suggest that patterns exhibited in recent history will intensify due to both changes in the threats and the assets within the State that are exposed. WILDLAND FIRE VS. WILDLAND-URBAN INTERFACE FIRES There are two primary types of wildfires: wildland-urban interface and wildland fire. This distinction is important because mitigation damage and actions related to the two types may differ significantly. California experiences an average of 5,000 wildland-urban interface fires each year. Wildland-urban interface is defined as “the area or zone where structures and other human development meet or intermingle with undeveloped wildland or vegetative fuels. RULE-MAKING AUTHORITY AND FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY IN CALIFORNIA Local government agencies (cities and counties) typically control the authority to enact and enforce land use ordinances, building codes, and fire codes for development within their boundaries. This land use authority includes those areas where the local agency shares fire protection responsibility with either federal or state agencies. Financial responsibility for fire protection is a significant issue because fire protection is very expensive and considerably more expensive in wildland-urban interface areas. URBAN FIRE CONFLAGRATION POTENTIAL Although the California State Hazard Mitigation Plan focuses primarily on wildfires, it recognizes urban conflagration, or a large disastrous fire in an urban area, as a major hazard that can occur due to many causes such as wildfires, earthquakes, gas leaks, chemical explosions, or arson. The urban fire conflagration that followed the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake did more damage than the earthquake itself. A source of danger to cities throughout human history, urban conflagration has been reduced as a general source of risk to life and property through improvements in community design, construction materials, and fire protection systems. For example, following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, improvements in architecture, building design, and construction materials helped to reduce the likelihood of recurrence. Subsequent improvements in construction have been encouraged throughout the U.S. by modern building and fire codes. The Great Chicago Fire burned approximately 2,000 acres and is estimated to have killed 200 to 300 people and damaged 17,500 buildings. It is interesting to note that on the same day as the wind-driven Great Chicago Fire, one of the most devastating wildlandurban interface fires in the United States history occurred in Peshtigo, Wisconsin. Driven by the same winds that spread the fire in Chicago, the fires in Wisconsin burned more than 1,000,000 III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 5 of 31 acres of forest, destroyed several entire towns, and killed more than 1,500 people. While the urban fire codes changed significantly after the Great Chicago Fire, wildland-urban interface fire codes have only recently gathered significant attention. Although the frequency of urban conflagration fires has been reduced, they remain a risk to human safety. One reason is the current trend toward increased urban density and infill in areas adjacent to the wildland-urban interface. In an effort to keep housing close to urban jobs, areas previously left as open space due to steep slopes and high wildland fire risk are being reconsidered as infill areas for high-density housing. A memorable example of urban conflagration linked to wildland fire in recent California history is the Oakland Hills firestorm, officially known as the Tunnel Fire. The October 20, 1991 fire occurred in portions of the cities of Oakland and Berkeley. In Oakland 2,777 units were destroyed or badly damaged. An additional 69 units were destroyed within the City of Berkeley. The fire happened in an economically well-off, largely built-out residential area that has a longstanding fire history linked to hot, dry fall winds and the presence of dense, flammable vegetation. Seasonably strong, dry winds drove flames furiously and rapidly across an approximately two-and-one-half square mile area of densely developed hillside neighborhoods. California has had a long history of disastrous wildland-urban interface fires beginning with the 1923 Berkeley Fire that destroyed 584 buildings while burning 123 acres. Repetitive wildland fires do occur, as noted above, a significant lesson about this 1923 fire is that wildland-urban interface fire revisited this same location in 1970 and again in 1991 with the most damaging wildland-urban interface fire in California history. Other important events in California history that caused changes in the approach to these fires were: The 1961 Bel Air Fire, which resulted in examination of wooden roofs in wildland-urban interface areas The 1970 Fire Siege, which resulted in development of the Incident Command System (ICS) The 1980 Southern California Fire Siege, which resulted in the creation of the CAL FIRE Vegetation Management Program The 1985 Fire Siege, which resulted in major expansion of local government fire service mutual aid on wildland-urban interface fires The 1988 49er Fire, which was identified as the “wildland-urban interface fire problem of the future” due to urban expansion from Sacramento metropolitan area into the Sierra foothills The 1991 Tunnel Fire which resulted in the creation of the Standardized Emergency Management System (SEMS) in California and legislation requiring Fire Hazard Severity Zone mapping in LRAs (AB 337-Bates) The 1993 Laguna Fire, which resulted in creation of the California Fire Safe Council concept and changes to flammable roofing codes The 2003 Fire Siege, which resulted in changes to defensible space clearances from 30 feet to 100 feet and formation of Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission on fires The 2007 Angora Fire, which resulted in a California-Nevada Governor’s Blue Ribbon Commission examination of wildland-urban interface issues in Lake Tahoe area The 2008 Sylmar Fire in Los Angeles, which led to revision of mobile home fire safety III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 6 of 31 The 2009 Station Fire in the Angeles National Forest which led to re-examination of wildland fire management in proximity to urban areas In October 2007, a series of large wildfires ignited and burned hundreds of thousands of acres in Southern California. The fires displaced nearly one million residents, destroyed thousands of homes, and took the lives of 10 people. Within the context of wildland fire, the Southern California Siege of 2007, along with the Angora Fire in South Lake Tahoe, demonstrated again a well-recognized fact that fire is an integral component of California’s ecosystems. The Angora Fire burned 3,100 acres and destroyed 242 homes and 67 commercial structures in June 2007. Wildfires are costly, comprising watersheds, open space, timber, range, recreational opportunities, wildlife habitats, endangered species, historic and cultural assets, wild and scenic rivers, other scenic assets and local economies, as well as putting lives and property at risk. FEMA DR-1810 was the result of extremely high winds and wildfires beginning November 13, 2008, and continuing through November 29, 2008 which impacted Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Santa Barbara counties. Winds, at times more than 70 miles per hour, played an integral role in worsening fire conditions by fanning the flames and spreading the wildfires with frightening speed. Fires consumed approximately 43,500 acres, destroying 858 homes, 10 businesses, and 110 outbuildings. In addition, 136 homes were severely damaged and a large number of home-based businesses and rental properties also experienced moderate damage. Threatened structures also included over 12,550 residences, 100 commercial buildings and 200 outbuildings causing widespread human injury; destruction and damage to homes, businesses, schools, hospitals and infrastructure throughout the region. State and local agency response costs were estimated at $15 million per day. On average 9,000 wildfires burn half a million acres in California annually. While the number of acres burned fluctuates from year to year, a trend that has remained constant is the rise in wildfire-related losses. Likewise, fires that originate in the wildfire-urban interface from structures or other improvements can cause damage to the wildland resources and nonwildland-urban interface assets at risk. The challenge is in how to reduce wildfire losses within a framework of California’s diversity. The following table shows the most disastrous wildlandurban interface fires listed in order of structures destroyed. Eighty percent of the most damaging wildland-urban interface fires have occurred in the last 20 years. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 7 of 31 Table 1 - Fire History by Number of Structures Destroyed FIRE HAZARD VS. FIRE RISK The diversity of wildland-urban interface settings and disagreement about alternative mitigation strategies have led to confusion and different methods of defining and mapping fire areas. One major disagreement has been caused by terms such as “hazard” and “risk” being used interchangeably. Hazard is the physical condition that can lead to damage to a particular asset or resource. The term “fire hazard” is related to those physical conditions related to fire and its ability to cause damage, specifically how often a fire burns a given locale and what the fire is like when it burns (its fire behavior). Thus, fire hazard only refers to the potential characteristics of the fire itself. Risk is the likelihood of a fire occurring at a given site (burn probability) and the associated mechanisms of fire behavior that cause damage to assets and resources (fire behavior). This includes the impact of fire brands (embers) that may be blown some distance igniting fires well away from the main fire. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 8 of 31 Figure 3 - State of California Fire Threat This CAL FIRE map shows wildfire threat wildly distributed across hilly and mountainous terrain throughout California. Threat is a measure of the potential fire severity. Urban areas are shown as facing a moderate threat in this model due to exposure from wildland-urban interface fires and windblown embers that could result in urban conflagration. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 9 of 31 Figure 4 - State and Federal Declared Fire Disasters from 1950 to 2009 This map shows declared wildfire disasters from 1950 to 2009. Highest numbers occurred in Southern California, showing the influence of major populated urban areas in Los Angeles and other nearby counties on fire emergency and disaster events. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 10 of 31 The following figure shows structures ignited by wildfire in California from 2000 through 2009. Overall, 5,000 wildfires have burned 200,000 acres in California. The numbers of ignited structures rose significantly with the Southern California wildfires of 2003 and then dropped back substantially in the period from 2004 through 2008. Figure 5 - Number of structures ignited in California 2000 to 2009 III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 11 of 31 Figure 6 - Wildfire Hazard Ranking in Local Hazard Mitigation Plans This map identifies wildfire hazards as being a predominant concern (51 percent of local jurisdictions) in the 2010 Local Hazard Mitigation Plans review for most Southern California and many San Francisco Bay Area counties, as well as many North Coast and Sierra Mountain counties. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 12 of 31 CALIFORNIA STRATEGIC FIRE PLAN The California State Board of Forestry and Fire Protection approved the 2010 Strategic Fire Plan in June 2010. The Strategic Fire Plan forms the basis for assessing California’s complex and dynamic natural and human-made environment and identifies a variety of actions to minimize the negative effects of wildland fire. Vision The vision of the Strategic Fire Plan is for a natural environment that is more resilient and human-made assets that are more resistant to the occurrence and efforts of wildland fire through local, state, federal and private partnerships. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 13 of 31 C. ORANGE COUNTY A variety of fire protection challenges exist within Orange County, including structure, urban fires, wildland fires, and fires in the wildland-urban interface. This hazard analysis of Orange County focuses on wildland fires, but also addresses issues specifically related to the wildlandurban interface and structure issues. Figure 7 – Orange County Wildland Fire Management Planning Areas III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 14 of 31 The provision of adequate fire protection is directly affected by residential, commercial and industrial growth, all of which are proceeding rapidly in Orange County. By 1960, manufacturing employed three times as many workers as the agricultural industry. Aerospace and other hightech industries began moving into the area, bringing with them growing affluence. Between 1950 and 1960, Orange County's median income grew from the 20th highest of California's 58 counties to the third highest. By the mid-1990s, Orange County's high-tech and information industries were among the most dynamic in the United States. By 1999, Orange County had a population of 2.85 million residents. Between 1990 and 2020, the population of the entire County is expected to increase by more than 500,000 or 21.6 percent, with a corresponding increase in demand for fire protection services (Statistics taken from the Orange County General Plan, 1999). WILDLAND URBAN INTERFACE In an effort to alleviate the dangers from wildland fires in or near the interface with urban development (wildland-urban interface), the construction of fuel modification zones (firebreak, fuel break, or greenbelt) are required. The application of this method does have limitations and is therefore only a part of the solution. Fire prevention measures that reduce the level of risk to the structures located in the wildland-urban interface must be further studied and developed in order to “harden the structure/home” and prevent the spread of wildland fire due to flying embers and radiant heat. Much of the following, which addresses the threat of fire to urban areas, wildlands and the wildland-urban interface, has been extracted from the information prepared by the Orange County Fire Authority for the Safety Element of the Orange County General Plan. Some of the most difficult fire protection problems in the urban area are: Multiple story, wood frame, high-density developments Large contiguous built up areas with combustible roof covering materials Transportation of hazardous materials by air, rail, road, water and pipeline Natural disasters Other factors contributing to major fire losses are: Delayed detection of emergencies Delayed notification to the fire agency Response time of emergency equipment Street structure – private, curvilinear and dead-end, street widths Inadequate and unreliable water supply with poor hydrant distribution Inadequate code enforcement and code revisions, which lag behind fire prevention knowledge Fire Prevention is the major fire department activity in urban areas; the objective is to prevent fires from starting. Once a fire starts, the objective is to minimize the damage to life and III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 15 of 31 property. Urban fire prevention programs that are designed to achieve this fire prevention objective are: Adoption and aggressive enforcement of the most recent Fire and Building Codes with state and local amendment addressing wildland fire hazards Development of a comprehensive master plan to ensure that staffing and facilities keep pace with growth Enforcement of Hazardous Materials Disclosure Ordinance Active participation in Planning Committees and other planning activities The character of the existing built-up area and future land use determines the location of fire stations, the number of fire companies, staffing of such companies, and future fire protection facility needs. Structural conditions also influence the quantity of water needed for fire protection (fire flow) and hydrant distribution. Features of structural conditions that affect fire control are: Type of construction, construction features, and use of buildings Area of building (ground floor area) Number of stories Type of roof covering material Exposures to the building WILDLAND FIRES California experiences large, destructive wildland fires almost every year and Orange County is no exception. Wildland fires have occurred within the county, particularly in the fall of the year, ranging from small, localized fires to disastrous fires covering thousands of acres. The most severe fire protection problem in the unincorporated areas is wildland fire during Santa Ana wind conditions. Figure 8 - Current fuel hazard ranking as of 2005 for Orange County. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 16 of 31 Reasons for control difficulty associated with wildland fires are: Adverse weather conditions Large quantities of contiguous combustible fuel beds Inaccessible terrain Nonexistent or very limited water supply Large fire fronts requiring dispersal of fire forces For these reasons, it is usually necessary for the firefighting force to meet the advancing fire front in an accessible area containing a minimum amount of combustible vegetation, and preferably located close to a water source. The major objective of wildland fire defense planning is to prevent wildland fires from starting and, if unsuccessful, to minimize the damage to natural resources and structures. Some of the more successful programs currently in effect which contribute to the success of wildland fire prevention activities are: Closure of public access to land in hazardous fire areas Building Code prohibition of most combustible roof covering materials (still allows the Class C) Local amendments requiring “special construction features,” e.g. boxed eaves, Class A roof, dual pained or tempered glass windows Construction and maintenance of community and private fuel modification zones Vegetative Management Program (controlled burning) Weed Abatement Program Fire Prevention Education Programs There are a number of natural conditions which dictate the severity of a wildland fire when it occurs. Three such conditions are weather elements, the topography of the area, and the type and condition of wildland vegetation. WEATHER Weather conditions have many complex and important effects on fire intensity and behavior. Wind is of prime importance; as wind increases in velocity, the rate of fire spread also increases. Relative humidity (i.e., relative dryness of the air) also has a direct effect; the drier the air, the drier the vegetation and the more likely the vegetation will ignite and burn. Precipitation (annual total, seasonal distribution and storm intensity) further affects the moisture content of both dead and living vegetation, which influences fire ignition and behavior. Many wildland fires have been associated with adverse weather conditions. In recent years, Orange County has experienced numerous wildland fires that have destroyed, damaged or threatened an extensive number of homes and businesses that relates to millions of dollars in property damage and loss of business revenue. The Sierra Incident in CY2006 burned 10,584 acres; the Santiago Incident in CY2007 burned 28,476 acres and either damaged or destroyed 23 residences and the Freeway Complex in CY2008 that burned 30,305 acres and either damaged or destroyed 300+ residences; are just a few examples of the devastation caused by III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 17 of 31 wildland fires. At the onset of these fires, the Santa Ana winds were exceeding 50 mph, making quick containment impossible. Additionally, the extreme fire weather conditions of 1993, aided the devastating firestorms that swept Laguna Beach and the County during the period of October 24 through November 4. During this period, a total of 20 major fires in six Southern California counties burned out of control, of which three of these fires occurred in Orange County: the Stagecoach fire burned 750 acres and destroyed 9 buildings, the Laguna Beach fire burned 14,337 acres, destroyed 441 homes and caused approximately $528 million in damage, and the Ortega fire burned 21,384 acres and destroyed 19 buildings. In 1997, the Baker Canyon fire by Irvine Lake burned 6,317 acres of vegetation, followed by two additional fires in 1998: The Blackstar/Santiago Canyons fire destroyed 8,800 acres, and the Carbon Canyon fire burned 733 acres of brush. In 2008 a wildfire was the result of extremely high winds and wildfires which impacted five counties including Orange County. Winds blew more than 70 miles per hour fanning the flames and spreading the wildfires with alarming speed. In addition to winds, structural development exposures within or adjacent to wildland represents an extreme fire protection problem due to flying embers and the predominance of combustible roof coverings. TOPOGRAPHY Topography has considerable effect on wildland fire behavior and, depending on the topography, may limit the ability of firefighters and their equipment to take adequate action to suppress or contain wildland fires. A wildland fire starting in a canyon bottom will quickly spread to the ridge top before initial attack forces arrive. Rough topography greatly limits fireline construction, road construction, road standards, and accessibility by ground firefighting resources. Steep topography also channels airflow, creating extremely erratic winds on leeward slopes, canyons and passes. Water supply, intended for protecting structures located at higher elevations, is frequently dependent on water pump stations and utilities. The source of power for such stations is usually from overhead electrical power distribution lines, which are subject to destruction by wildland fires. VEGETATION A key to effective fire control and the successful accommodation of fire in wildland management is the understanding of fire and its environment. The fire environment is the combination of combustible fuels, topography, and air mass and the complexity of these factors play an important role to influence the inception, growth, and behavior of a fire. The topography and weather components are, for all practical purposes, beyond human control, but it is a different story with fuels, which can be controlled before the outbreak of fires. In terms of future urban expansion, finding new ways to control and understand these fuels can lead to possible fire reduction. A relatively large portion of the county is covered by natural (though modified) vegetation as indicated on the Composite Vegetation Map provided by the Orange County Fire Authority. Of these different vegetation types, coastal sage scrub, chaparral, and grasslands become the III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 18 of 31 most hazardous, with a high probability of ignition, during the dry summer months and, under certain conditions, during the winter months. For example, as chaparral gets older, twigs and branches within the plants die and are held in place. A stand of brush 10- to 20-years of age will contain dried and cured dead material that can produce a rate of spread comparable to grass fires. In severe drought years, additional plant material may die, contributing to the fuel load. There will normally be enough dead fuel accumulated in 20- to 30-year old brush to give rates of spread approximately twice as fast as in a grass fire. An example is; under moderate weather conditions in a grass vegetation type a rate of spread of one-half foot per second can be expected, conversely a vegetation type of 20- to 30-year old stand of chaparral may have a rate of fire spread of about one foot per second. Fire spread in old brush (40 years or older) has been measured at eight times as fast as in grass, about four feet per second. Under extreme weather conditions, the fastest fire spread in grass is 12 feet per second or about eight miles per hour. Figure 9 – Orange County Vegetation Approximately 98% of the Coast Community College District is in the #10 Urban Zone. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 19 of 31 WILDLAND FIRES AS A THREAT TO SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Wildland fire is a natural part of the ecosystem in Southern California. However, wildland fire presents a substantial hazard to life and property in communities built in or adjacent to the open spaces of Orange County. There is a huge potential for losses due to Wildland Urban Interface fires in Southern California. The fall of 2007 marked on of the most destructive wildland fire season in California history. In a four day period from 10/20/07 thru 10/23/07, 20 separate fires started and raged across Southern California in Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside, Orange and San Diego counties. The massive Witch Incident in San Diego County alone consumed of 1,218 homes and burned over 197,990 acres. Orange County had the Santiago fire on October 21, 2007 which burned 28,400 acres. There were 15 homes lost, eight homes damaged and fortunately no lives lost. WILDLAND FIRE CHARACTERISTICS There are three categories of wildland-urban interface: the classic exists where well-defined urban and suburban development presses up against open expanses of wildland areas, the mixed wildland-urban interface is characterized by isolated homes, subdivisions and small communities situated predominantly in wildland settings, and the occluded wildland-urban interface existing where islands of wildland vegetation occur inside a largely urbanized area. Certain conditions must be present for significant interface fires to occur. The most common conditions include: hot, dry and windy weather, the inability of firefighting forces to contain or suppress the fire, the occurrence of multiple fires that overwhelm committed resources, and a large fuel load (dense vegetation). Once a fire has started, several conditions influence its behavior, including fuel, topography, weather, drought, and development. Southern California has two distinct areas of risk for wildland fire. The foothills and lower mountain areas are most often covered with scrub brush or chaparral. The higher elevations of mountains also have heavily forested terrain. The higher elevations of Southern California’s mountains are typically heavily forested. The magnitude of the 2003, 2007 and 2008 fires is the result of three primary factors: (1) weather conditions including severe drought, a series of storms that produce thousands of lightning strikes and windy conditions; (2) infestations of a variety of beetles and other pests that has killed thousands of mature trees; and (3) the cumulative effects of wildland fire suppression over the past century that has resulted in an overabundance of brush and small diameter trees in the forests. At the beginning of the 1900s, forests were relatively open, with 20 to 25 mature trees per acre. Periodically, lightning would start fires that would clear out underbrush and small trees, renewing the forests. Today's forests are completely different, with as many as 400 trees crowded onto each acre, along with thick undergrowth. This density of growth makes forests susceptible to disease, drought and severe wildland fires. Instead of restoring forests, these wildland fires destroy them and it can take decades to recover. This radical change in our forests is the result of nearly a century of well-intentioned but misguided management. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 20 of 31 THE INTERFACE One challenge Southern California faces regarding the wildland fire hazard is from the increasing number of houses being built in the wildland urban interface. Every year the growing population expands further and further into the hills and mountains, including forest lands. The increased "interface" between urban/suburban areas and the open spaces created by this expansion has produced a significant increase in threats to life and property from fires and has pushed existing fire protection systems beyond original or current design and capability. Many property owners in the interface are not aware of the problems and threats they face. Therefore, many owners must do more to manage or offset fire hazards or risks on their own property. Furthermore, human activities increase the incidence of fire ignition and potential damage. FUEL Fuel is the material that feeds a fire and is a key factor in wildland fire behavior. Fuel is classified by volume and by type. Fuel volume is described in terms of “fuel loading,” or the amount of available vegetative fuel. Fuel type is an identifiable association of fuel elements of distinctive species, form, size, arrangement, or other characteristics that will cause a predictable rate of spread or resistance to control under specified weather conditions. Chaparral is a primary fuel type in Southern California and the basis of the extreme conditions associated with wildland fires. Chaparral habitat ranges in elevation from near sea level to over 5,000' in Southern California. Chaparral communities experience long dry summers and receive most of their annual precipitation from winter rains. Fire has been important in the life cycle of chaparral communities for over 2 million years; however, the true nature of the "fire cycle" has been subject to interpretation. In a period of 750 years, it is generally thought that fire occurs once every 65 years in coastal drainages and once every 30 to 35 years inland. The vegetation of chaparral communities has evolved to a point it requires fire to spawn regeneration. Many species invite fire through the production of plant materials with large surface-to-volume ratios, volatile oils and through periodic die-back of vegetation. These species have further adapted to possess special reproductive mechanisms following fire. Several species produce vast quantities of seeds which lie dormant until fire triggers germination. The parent plant which produces these seeds defends itself from fire by a thick layer of bark which allows enough of the plant to survive so that the plant can crown sprout following the blaze. In general, chaparral community plants have adapted to fire through the following methods: a) fire induced flowering, b) bud production and sprouting subsequent to fire, c) in-soil seed storage and fire stimulated germination, and d) on plant seed storage and fire stimulated dispersal. An important element in understanding the danger of wildland fire is the availability of diverse fuels in the landscape, such as natural vegetation, manmade structures and combustible materials. A house surrounded by brushy growth rather than cleared space allows for greater continuity of fuel and increases the fire’s ability to spread. After decades of fire suppression III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 21 of 31 “dog-hair" thickets have accumulated, which enable high intensity fires to flare and spread rapidly. TOPOGRAPHY Topography influences the movement of air, thereby directing a fire course. For example, if the percentage of uphill slope doubles, the rate of spread in wildland fire will likely double. Gulches and canyons can funnel air and act as chimneys, which intensify fire behavior and cause the fire to spread faster. Solar heating of dry, south-facing slopes produces up slope drafts that can complicate fire behavior. Unfortunately, hillsides with hazardous topographic characteristics are also desirable residential areas in many communities. This underscores the need for wildland fire hazard mitigation and increased education and outreach to homeowners living in interface areas. WEATHER Weather patterns combined with certain geographic locations can create a favorable climate for wildland fire activity. Areas where annual precipitation is less than 30 inches per year are extremely fire susceptible. High-risk areas in Southern California share a hot, dry season in late summer and early fall when high temperatures and low humidity favor fire activity. The socalled “Santa Ana” winds, which are heated by compression as they flow down to Southern California from the Great Basin Region, create a particularly high risk, as they can rapidly spread what might otherwise be a small fire. DROUGHT Recent concerns about the effects of climate change, particularly drought, are contributing to concerns about wildland fire vulnerability. The term drought is applied to a period in which an unusual scarcity of rain causes a serious hydrological imbalance. Unusually dry winters, or significantly less rainfall than normal, can lead to relatively drier conditions and leave reservoirs and water tables lower. Drought leads to problems with irrigation and may contribute to additional fires, or additional difficulties in fighting fires. DEVELOPMENT Growth and development in scrubland and forested areas is increasing the number of humanmade structures in Southern California interface areas. Wildland fire has an effect on development, yet development can also influence wildland fire. Owners often prefer homes that are private, have scenic views, are nestled in vegetation and use natural materials. A private setting may be far from public roads, or hidden behind a narrow, curving driveway. These conditions, however, make evacuation and fire fighting difficult. The scenic views found along mountain ridges can also mean areas of dangerous topography. Natural vegetation contributes to scenic beauty, but it may also provide a ready trail of fuel leading a fire directly to the combustible fuels of the home itself. WILDLAND FIRE HAZARD ASSESSMENT Wildland fire hazard areas are commonly identified in regions of the Wildland Urban Interface. Ranges of the wildland fire hazard are further determined by the ease of fire ignition due to natural or human conditions and the difficulty of fire suppression. The wildland fire hazard is also magnified by several factors related to fire suppression/control such as the surrounding fuel load, weather, and topography and property characteristics. Generally, hazard identification rating systems are based on weighted factors of fuels, weather and topography. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 22 of 31 THE THREAT OF URBAN CONFLAGRATION Although communities without wildland-urban interface are much less likely to experience a catastrophic fire, in Southern California there is a scenario where any community might be exposed to an urban conflagration similar to the fires that occurred following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. The photo to the left is of an arson fire that occurred in Huntington Beach on Thanksgiving Day in 1986. FIRE FOLLOWING EARTHQUAKE Large fires following an earthquake in an urban region are relatively rare phenomena, but have occasionally been of catastrophic proportions. The two largest peace-time urban fires in history, 1906 San Francisco and 1923 Tokyo, were both caused by earthquakes. The fact that fire following an earthquake has been little researched or considered in the United States is particularly surprising when one realizes that the conflagration in San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake was the single largest urban fire, and the single largest earthquake loss, in U.S. history. The loss over three days of more than 28,000 buildings was staggering: $250 million in 1906 dollars, or about $5 billion at today’s prices. The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, the 1991 Oakland hills fire, and Japan’s recent earthquake all demonstrate the current, real possibility of a large fire, such as a fire following an earthquake, developing into a conflagration. In the United States, all the elements that would hamper firefighting capabilities are present: density of wooden structures, limited personnel and equipment to address multiple fires, debris blocking the access of fire-fighting equipment, and a limited water supply. This scenario highlights the need for fire mitigation activity in all sectors of the region, wildlandurban interface or not. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 23 of 31 FIRE CODES LOCAL FIRE AND BUILDING CODES The State Fire and Building Codes currently contain few regulations for protection of structures from wildland fires. An Appendix to the California Fire Code, which must be locally adopted in order to have enforcement authority, contains extracts from the Public Resource Code relative to minimum brush clearances (30 to 100 feet) and safety in interface areas. Many local jurisdictions develop local amendments that more specifically address risks within their communities. The Orange County Fire Authority, through its partner cities and the County, adopt fuel modification standards (170 feet minimum) and building construction requirements (Class A roofs, boxed eaves, protected vents, dual paned windows, etc.) applicable in identified fire hazard areas. COUNTY FIRE CODES Most of key sections of county codes are local amendments to the State Fire Code, including brush clearance (fuel modification) and construction features (roofs, eaves, etc.) that apply to wildland-urban interface areas are covered in the State Fire Code. STATE FIRE CODES California Fire Code 2001 (For fuel modification and enforcement of hazardous fuels within populated areas.) Section 27, Appendix 2-A-1 Article 11, Section 1103.2.4 CALIFORNIA PUBLIC RESOURCES CODE DIVISION 4. FORESTS, FORESTRY AND RANGE AND FORAGE LANDS PART 1. DEFINITIONS AND GENERAL PROVISIONS CHAPTER 1. DEFINITIONS ........................................ 4001-4004 CHAPTER 2. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1. Penalties ......................................... 4021-4022 Article 2. Purchase of Land ..................................... 4031 PART 2. PROTECTION OF FOREST, RANGE AND FORAGE LANDS CHAPTER 1. PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF FOREST FIRES Article 1. Definitions ....................................... 4101-4104 Article 2. General Provisions ................................ 4111-4123 Article 3. Responsibility for Fire Protection ................ 4125-4136 Article 3.5. State Responsibility Area Fire Protection Benefit Fees .................................. 4138-4140.7 Article 4. Cooperative Agreements ............................ 4141-4145 Article 5. Firewardens and Firefighting Personnel ......4151-4157 Article 6. Violations ...................................... 4165-4170.5 Article 7. Public Nuisances .................................. 4171-4181 Article 8. Clarke-McNary Act ................................. 4185-4187 Article 9. Fire Hazard Severity Zones ........................ 4201-4205 CHAPTER 2. HAZARDOUS FIRE AREAS ................ 4251-4290 CHAPTER 3. MOUNTAINOUS, FOREST-, BRUSH- AND GRASS-COVERED LANDS .............................................. 4291-4299 CHAPTER 4. RESTRICTED AREAS ........................ 4331-4333 CHAPTER 6. PROHIBITED ACTIVITIES III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 24 of 31 Article 1. Definitions and General Provisions ............ 4411-4418 Article 2. Prohibited Activities ............................. 4421-4446 CHAPTER 7. BURNING OF LANDS Article 1. Experimental Program for Wildland Fire Protection and Resources Management .......................... 4461-4473 Article 2. Department of Forestry Burning Contracts . 4475-4480 Article 3. Private Burning of Brush-Covered Lands Under Permit 4491-4494 CHAPTER 10. PROTECTION OF FOREST AND LANDS Article 8. Wildland Fire Prevention and Vegetation Management. 4740-4741 FEDERAL PROGRAMS The role of the federal land management agencies in the wildland-urban interface is to reduce fuel hazards on the lands they administer; cooperating in prevention and education programs; providing technical and financial assistance; and developing agreements, partnerships and relationships with property owners, local protection agencies, states and other stakeholders in wildland-urban interface areas. These relationships focus on activities before a fire occurs, which render structures and communities safer and better able to survive a fire occurrence. FEDERAL EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AGENCY (FEMA) PROGRAMS FEMA is directly responsible for providing fire suppression assistance grants and, in certain cases, major disaster assistance and hazard mitigation grants in response to fires. The role of FEMA in the wildland-urban interface is to encourage comprehensive disaster preparedness plans and programs, increase the capability of state and local governments and provide for a greater understanding of FEMA programs at the federal, state and local levels. FIRE SUPPRESSION ASSISTANCE GRANTS This type of grant may be provided to a state with an approved hazard mitigation plan for the suppression of a forest or grassland fire that threatens to become a major disaster on public or private lands. These grants are provided to protect life and improved property, encourage the development and implementation of viable multi-hazard mitigation measures, and provide training to clarify FEMA's programs. The grant may include funds for equipment, supplies and personnel. A Fire Suppression Assistance Grant is the form of assistance most often provided by FEMA to a state for a fire. The grants are cost-shared with states. FEMA’s US Fire Administration (USFA) provides public education materials addressing Wildland Urban Interface issues and the USFA's National Fire Academy provides training programs. HAZARD MITIGATION GRANT PROGRAM Following a major disaster declaration, the FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program provides funding for long-term hazard mitigation projects and activities to reduce the possibility of damages from all future fire hazards and to reduce the costs to the nation for responding to and recovering from the disaster. NATIONAL WILDLAND URBAN INTERFACE FIRE PROTECTION PROGRAM Federal agencies can use the National Wildland Urban Interface Fire Protection Program to focus on Wildland Urban Interface fire protection issues and actions. The Western Governors' Association (WGA) can act as a catalyst to involve state agencies, as well as local and private stakeholders. The objective is to develop an implementation plan to achieve a uniform, integrated national approach to hazard and risk assessment using fire prevention and protection III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 25 of 31 in the Wildland Urban Interface. The program helps states develop viable and comprehensive wildland fire mitigation plans and performance-based partnerships. U.S. FOREST SERVICE The U. S. Forest Service (USFS) is involved in a fuel-loading program implemented to assess fuels and reduce hazardous buildup on National Forest lands. The USFS is a cooperating agency and, while it has little to no jurisdiction in the lower valleys, it has an interest in preventing fires in the forested lands in the interface, due to the likelihood that a wildland fire can spread from either jurisdiction onto the adjoining jurisdiction. OTHER MITIGATION PROGRAMS AND ACTIVITIES Some areas of the country are facing wildland-urban interface issues collaboratively. These are model programs that include local solutions. Summit County, Colorado, has developed a hazard and risk assessment process that mitigates hazards through zoning requirements. In California, the Los Angeles County Fire Department and Orange County Fire Authority have retrofitted more than 150 fire engines with fire retardant foam capability and Orange County is developed a rating schedule specific to the wildland-urban interface to determine areas and structures susceptible to wildland fire. All are examples of successful programs that demonstrate the value of pre-suppression and prevention efforts when combined with property owner support to mitigate hazards within the wildland-urban interface. PRESCRIBED BURNING The health and condition of a forest will determine the magnitude of wildland fire. If fuels, dry or dead vegetation, fallen limbs and branches--are allowed to accumulate over long periods of time without being methodically cleared; fire can move more quickly and destroy everything in its path. The results are more catastrophic than if the fuels are periodically eliminated. Prescribed burning is the most efficient method to get rid of these fuels. In California during 2003, various fire agencies conducted over 200 prescribed fires and burned over 33,000 acres to reduce the wildland fire hazard. FIREWISE Firewise is a program developed within the National Wildland/Urban Interface Fire Protection Program and it is the primary federal program addressing interface fire. It is administered through the National Wildland Fire Coordinating Group whose extensive list of participants includes a wide range of federal agencies. The program is intended to empower planners and decision makers at the local level. Through conferences and information dissemination, Firewise increases support for interface wildland fire mitigation by educating professionals and the general public about hazard evaluation and policy implementation techniques. Firewise offers online wildland fire protection information and checklists, as well as listings of other publications, videos and conferences. The interactive home page allows users to ask fire protection experts questions and to register for new information as it becomes available. FIREFREE PROGRAM FireFree is a unique private/public program for interface wildland fire mitigation involving partnerships between an insurance company and local government agencies. It is an example of an effective non-regulatory approach to hazard mitigation. Originating in Bend, Oregon, the program was developed in response to the city's "Skeleton Fire" of 1996, which burned over 17,000 acres and damaged or destroyed 30 homes and structures. Bend sought to create a III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 26 of 31 new kind of public education initiative that emphasized local involvement. SAFECO Insurance Corporation was a willing collaborator in this effort. Bend's pilot program included: A short video production featuring local residents as actors, made available at local video stores, libraries and fire stations Two city-wide yard debris removal events A 30-minute program on a model FireFree home, aired on a local cable television station Distribution of brochures, featuring a property owner evaluation checklist and a listing of fire-resistant indigenous plants WILDLAND FIRE MITIGATION ACTION ITEMS As stated in the Federal Wildland Fire Policy, located at www.fs.fed.us “The problem is not one of finding new solutions to an old problem but of implementing known solutions; deferred decision making is as much a problem as the fires themselves. If history is to serve us in the resolution of the wildland-urban interface problem, we must take action on these issues now. To do anything less is to guarantee another review process in the aftermath of future catastrophic fires.” III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 27 of 31 D. COAST COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICT A variety of fire protection challenges exist within Orange County, including structure, urban fires and wildland-urban interface fires. This table breaks down that threat by CCCD site: Table 2 - CCCD Sites located in OC Wildland and Urban Fire Planning Areas Identifier A1* A2 A3* B1* B2 C1* D1* D2 D3 D4* D5 D6 D7 D8 D9 Site Name/City College District Office, CM KOCE Transmitter La Habra Heights (LA County) Transportation Facility, CM Orange Coast College, CM Orange Coast Sailing Center, NB Golden West College, HB Coastline Administrative Center, FV Coastline Art Gallery, HB Coastline Costa Mesa Center, CM Coastline Garden Grove Center, GG Coastline Le-Jao Center Westminster Coastline Newport Beach Center NB Coastline OC Regional One Stop-Irvine Coastline OC Regional One Stop Center Westminster Coastline Tech Center, FV Owned or Leased OC Urban-Wildland Interface Fire Threat Urban Fire Threat Fire Department North Area Central Coastal Area South Area Owned No No No Yes Costa Mesa Fire Department Owned Yes No No Yes Los Angeles County Fire Dept Owned No No No Yes Owned No No No Yes Owned No No No Yes Newport Beach Fire Department Owned No No No Yes Huntington Bch Fire Department Owned No No No Yes Fountain Valley Fire Department Owned No No No Yes Leased No No No Yes Owned No No No Yes Owned No No No Yes Orange County Fire Authority Owned No No No Yes Newport Beach Fire Department Leased No Yes No Yes Orange County Fire Authority Leased No No No Yes Orange County Fire Authority Leased No No No Yes Fountain Valley Fire Department III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 28 of 31 Costa Mesa Fire Department Costa Mesa Fire Department Huntington Bch Fire Department Costa Mesa Fire Department Garden Grove Fire Department CCCD’S WILDLAND-URBAN INTERFACE FIRE THREAT This table above is based on the Orange County Wildland Fire Management Planning Area map (shown to the right) to determine which CCCD sites are located in a wildland-urban interface and urban fire planning areas. The following are the results of this study: Only four CCCD sites are threatened by a wildfire: KOCE Transmitter in La Habra Heights in Los Angeles County o The Fire Department for this site is Los Angeles County Fire Department Coastline Newport Beach Center in Newport Beach o The Fire Department responsible for this site is the Newport Beach Fire Department Orange Coast Sailing Center in Newport Beach o The Fire Department responsible for this site is the Newport Beach Fire Department Coastline OC Regional One Stop in Irvine o The Fire Department responsible for this site is the Orange County Fire Authority CCCD URBAN FIRE CONFLAGRATION POTENTIAL All CCCD sites are vulnerable to urban fires. The sites should ensure they meet all local and state fire prevention codes. III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 29 of 31 E. WILDLAND/URBAN FIRE H AZARD M ITIGATION STRATEGIES Hazard: Action Item: Wildland/Urban Fire #1 Educate Maintenance & Operations Directors responsible for the four identified wildland-urban interface sites on their fire threat and how to reduce the amount of combustible fuels. The four sites are: 1. KOCE Transmitter in La Habra Heights, Los Angeles County 2. Coastline Newport Beach Center in Newport Beach. 3. Orange Coast Sailing Center in Newport Beach. 4. Coastline OC Regional One Stop in Irvine Coordinating EHS/Emergency Management Coordinator will provide educational information Organization: to the Maintenance & Operations Directors of each of the identified four site Ideas for Find educational DVDs and handouts and provide them to Maintenance & Implementation: Operations directors. Access the National Wildland Fire Coordinating Group on line for appropriate educational information. Time Line: 1 year Constraints: Time Plan Goals Addressed X Promote Public Awareness Create Partnerships and Implementation Protect Life and Property Protect Natural Systems Strengthen Emergency Services Hazard: Action Item: Coordinating Organization: Ideas for Implementation: Wildland/Urban Fire #2 Review educational materials and determine additional fire prevention measures needed for the four identified wildland-urban interface potential sites. Sites include: 1. KOCE Transmitter in La Habra Heights, Los Angeles County 2. Coastline Newport Beach Center in Newport Beach. 3. Orange Coast Sailing Center in Newport Beach. 4. Coastline OC Regional One Stop in Irvine Maintenance & Operations Directors Review the educational materials from the National Wildland Fire Coordinating Group and study fire prevention codes to determine measures needed Purchase any needed supplies Schedule maintenance personnel to reduce the amount of combustible fuels at the four identified sites Time Line: Constraints: 1 year Maintenance & Operations divisions have had budget and personnel cuts; regular maintenance is difficult at this time but adding to the maintenance schedule will be extremely difficult Plan Goals Addressed Promote Public Awareness Create Partnerships and Implementation X Protect Life and Property Protect Natural Systems Strengthen Emergency Services III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 30 of 31 Hazard: Action Item: Coordinating Organization: Ideas for Implementation: Wildland/Urban Fire #3 Meet all Community College, State and Local fire codes and maintain all facilities in compliance Maintenance & Operations Directors 1. Review California Community College, State and Local fire codes 2. Determine any codes not met 3. Develop a plan to meet the codes 4. Purchase supplies needed 5. Schedule personnel 6. Maintain fire codes Time Line: 1 year Constraints: Maintenance & Operations divisions have had budget and personnel cuts; regular maintenance is difficult at this time but adding to the maintenance schedule will be extremely difficult. Any additional supplies or equipment needed must be scheduled through the college budget process Plan Goals Addressed Promote Public Awareness Create Partnerships and Implementation X Protect Life and Property Protect Natural Systems Strengthen Emergency Services III-E Wildland/Urban Fire Page 31 of 31