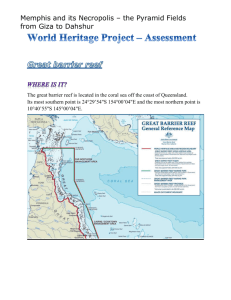

State Party Report on the state of conservation of the Great Barrier

advertisement