A summer study of young people who were enrolled in Youth

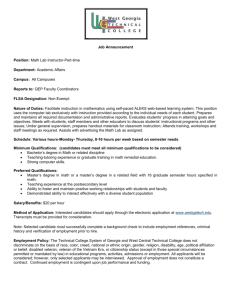

advertisement