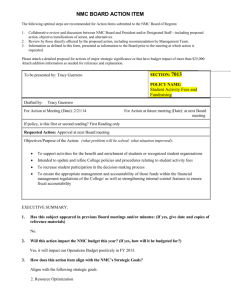

Accessible - Clinical Skills Managed Educational Network

advertisement