Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), Religiosity

advertisement

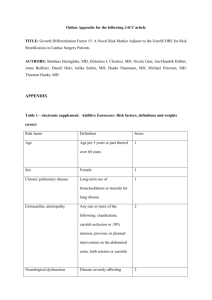

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), Religiosity and Depressive Symptoms among elderly Mexican Americans Veronika N. Stiles Biostatistics 524 Data Analytic Project University of Michigan Clinical Research Design and Statistical Analysis Program May 10, 2012 INTRODUCTION Depression is a major health problem for older adults.1 An extensive body of research suggests that Mexican-Americans report greater depressive symptomotology compared to non-Hispanic Whites and African Americans.2,3,4 Literature review has provided the number of demographic and social factors identified consistently in previous research as predictors of depressive symptoms in Mexican- Americans including but not limited to low formal education, low income, immigration status/country of birth, and religiosity. 5,6 Specifically in regards to religiosity, patients who frequently use religion to cope with stress have the lowest level of cognitive symptoms of depression. 7 Health-related identified predictors for elevated depressive symptoms include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hip fracture, pulmonary disease, significant breathing problems, cancer, arthritis, stomach ulcers, kidney disease, urinary and bladder incontinence. 8,9,10,11 All of these health-related predictors significantly impact the instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), which for the purposes of this project defined as driving, preparing meals, doing housework, shopping, managing finances, managing medication, and using the telephone. Primarily, this data analytic project aims to explore the association between instrumental activities of daily living, religiosity and depression among elderly Mexican-Americans and to identify the factors that might compound this association. Secondarily, whether or not the effect of IADL based on gender or nativity will be explored in this project. METHODS Sample The sample consists of 1,682 elderly Mexican-American subjects. Measures Dependent variable- Depressive symptoms were measured with Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the most widely used depression scale in studies with older adults. Higher scores indicate greater levels of depressive symptoms. The CES-D scores range form 0-60. Previous research studies have used score greater or equal to 16 as a dichotomous indication of high depressive symptoms. 2 However, for the purposes of this project CES-D scores will be predicted by the regression models as a continuous variable. Independent variables- The main independent variables of interest are the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) with potential range of 0-10; higher scores indicating a greater number of IADL problems) and religiosity (1=very religious; 2=moderately religious; 3=neutral; 4=not religious at all). Covariates—To account for potential confounding variables, the following health-related variables that might be associated with depressive symptoms were controlled for : hypertension, as well as scores on Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) and scores for Activities of Daily Living (ADL). Demographics-Demographic characteristic variables that were controlled for included gender (1=male; 0=female); nativity (US born; 1=born in the US; 0=not born in the US); highest grade completed, and marital status. Statistical Analyses All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) to adjust for complex sample design. Descriptive statistics and identification of outliers and normality of each variable distribution were performed before bivariate and multiple linear regression analyses. Upon data examination using histograms and quantile-quantile plots, the variables of grade, IADL, ADL were skewed to the right, and the variable MMSE was skewed to the left. A major outlier of 999 was identified for the outcome variable of CES-D total. These variables were converted to their natural logarithmic values to normalize the skewed distributions and to address the issue of outliers. Upon univariate data analysis, it was noted that the following data was missing: missing data for grade (n=25), missing data for number of living sons/daughters (n=9), missing data for high blood pressure (n=14), missing data for diabetes (n=3), missing data for hip fracture (n=2), missing data for high cholesterol (n=45), missing data for mini mental status exam (MMSE) (n=93), missing data for CES-D score (n=120), missing data for IADL (n=10), missing data for activities of daily living (ADL) (n=17), missing data for life satisfaction (n=161), missing data for religiosity (n=153), and missing data if respondent is bedridden (n=108). A comparison of participants with missing data to participants with deleted missing values (Table 1, 2) showed no meaningful differences with respect to the following continuous variables: grade, age, number of living children, health, MMSE, CES-D score, IADL, ADL, and religiosity. Missing data for the categorical variables of hypertension equals to 0.83% of all observations; diabetes equals to 0.18% of all observations; hip fracture equals to 0.12% of all observations; high cholesterol equals to 2.68% of all observations; and missing data if the patient is bedridden equals to 6.42% of all observations. The latter is the only significant percentage of missing data from the group. This fact should be noted in the limitations section of the paper if the investigators decided to omit all missing values. By default, SAS procedures handle missing values by omitting missing data. Another way of approaching missing value issue is by imputing missing values using best subset regression. However, this approach is beyond the scope of current project. In this project, the following associations were tested: 1) IADL and CES-D controlling for age, subject’s nativity, marital status, grade, gender; MMSE, ADL; and HBP, diabetes and hip fracture; 2) Religiosity and CES-D controlling for for age, subject’s nativity, marital status, grade, gender; MMSE, ADL; and HBP, diabetes and hip fracture; 3) IADL, religiosity and CES-D controlling for subject’s nativity, marital status, grade, gender; MMSE, ADL; and HBP; 4) Interaction effect of MMSE and religiosity on CES-D (rationale: previous research suggests that depressive symptoms have been reported as a risk factor for cognitive decline and church attendance has been associated with fewer depressive symptoms.) 12 In bivariate analyses of the continuous covariates, only age (P=0.0019), total score on MMSE, IADL, ADL (transformed; P<.0001) were significantly associated with CES-D scores (transformed). Highest grade completed was not significantly associated with CES-D (P=0.2739). Simple linear regression was performed to evaluate for any significant associations between CES-D score and subject’s nativity, marital status, gender, religiosity; diagnosis of high blood pressure, diabetes, and hip fracture. Subject nativity (P=0.0092), marital status (P<0.0001), male (P<0.0001), religiosity (P=0.0008), HBP (P<0.0001), diabetes (P=0.0153) were significantly associated with CES-D scores. Hip fracture was not significantly associated with CES-D (P=0.1618). In a multiple regression analysis, depressive symptoms (CES-D) were regressed on IADL (Table 3, Model 1) and religiosity (Table 4, Model 2) separately, adjusting for age, subject’s nativity, marital status, grade, gender; MMSE, ADL; and HBP, diabetes and hip fracture. Model 3 (Table 5) included both IADL and religiosity as predictors, adjusting for relevant risk factors. Model 4 (Table 6) presented MLR parameter estimates of CES-D scores as a function of MMSE, religiosity and their interaction term. Using an automated model building method of stepwise selection, final fully adjusted model is obtained. Model diagnostics is performed consequently to check for model assumptions. Assumptions for multiple linear regression models include: 1) Residuals follow the Normal distribution. Analysis of residuals by regressors indicates that distribution is skewed to the right for the log_totmmse4 regressor only. Hypertension, gender, marital status and nativity are categorical variables. 2) Constant variance assumption. There is a slight fan-shape noted amongst the residuals of the log_totmmse regressor. 3) True relationship is linear. The assumption appears to hold true. Results of this analysis are presented in Table 8. 4) To check for the presence of multicollinearity, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) were measured and all of them were less than 2, well below the threshold (VIF=10) that would indicate a problem of multicollinearity in a multivariate regression model. Therefore, the assumption of independence of each observation from all others holds true for the purposes of this analysis. When testing whether or not the effect of the log_ IADL on log_CESD varies by gender or nativity, multiple linear regression techniques were used. Results In an unadjusted model predicting CES-D by IADL, the estimated change in mean log CES-D for a 1 unit increase in IADL is 0.36 (P<.0001, SE=0.02731; 95% CI=0.31134; 0.41849).In an unadjusted model predicting CES-D by the religiosity, the estimated change in mean log CES-D for a 1 unit increase in religiosity is 0.15 (P=0.0008, SE=0.04576; 95% CI=0.06346; 0.24299). Unadjusted models are not shown in this analysis. Regression Model 1 (Table 3) presents beta coefficients for the prediction of continuous log_CES-D scores by log_IADL, adjusting for age, nativity, marital status, grade completed, gender, MMSE scores, ADL scores, hypertension, diabetes, and hip fracture. Similarly, Model 2 indicates a significant association between religiosity and log_CES-D scores with adjustments for relevant individual factors. In Model 3 with both transformed IADL and religiosity included in the model, there was an estimated change in mean log_CES-D score for a 1 unit increase in log_IADL of 0.27 (SE=0.35; P<0.0001; 95% CI (0.19791; 0.33252). There was an estimated change in mean log_CES-D score for 1 a unit increase in religiosity of 0.19 (SE=0.04; P<.0001; 95% CI (0.10496; 0.27324). Additional analysis results for testing the interaction effect between log_totalMMSE and religiosity as an additional predictor variable reported in Model 4 indicates a non-significant association (P =0.9729). Model 5 is the summary of the stepwise selection automated model building method. It is, however, the same model that was obtained by the multiple linear regression model reported as Model 3, excluding the non-significant findings. Variables age (P=0.2361), diabetes (P=0.9845) and hip fracture (P=0.8865) were excluded from further analysis. Final Multiple Regression Model for the continuous log_CES-D scores with 95% confidence intervals is reported in Table 9. Overall, R2 for the final fully adjusted model is 0.1718. The adjusted R2 for the model is 0.1665. In this model, only 16.65% of the variation in log_CES-D scores that is collectively explained by the log_IADL scores and the level of religiosity, adjusting for the relevant individual factors. To answer the secondary question of whether or not the effect of log_IADL varies by gender or nativity (adjusting for relevant individual factors), multiple linear regression technique was used to perform this analysis. In the analysis of gender (1=male, 0=female), “male 1” was used as a reference category. As a result, there was significant difference between males and females (P=0.0023, SE=0.06969, 95% CI (0.075919; 0.34936). In the analysis of nativity (0=not born in the US, 1=born in the US), the difference was also significant (P=0.0055, SE=0.0621; 95% CI (0.050986375; 0.294739). In this case, “US born 1” was used as a reference category. Conclusion The fully adjusted model from this data analytic project generally echoed the findings from the previous research. Having one or more IADL limitations was significantly associated with depressive symptoms in previous research. Church attendance, on the other hand, has been reported to be associated with fewer depressive symptoms.12 Surprisingly, diabetes was not a part of the final model, even though previous literature reports it as a highly prevalent disease in Mexican Americans and has been found to be associated with increased rates of depressive symptomotology.2 In conclusion, an increased understanding of depressive symptoms as a function of IADL limitations and level of religiosity can improve clinical practices and public health policies for Mexican American populations. However, the practical application and the clinical significance of estimated changes in the mean log_CES-D scores as a function of log_IADL scores and the level of religiosity should be questioned and examined further in future studies. Table 1. Characteristics of Participants with Missing Data Variables (N=1,682) Variable Label N Mean Std Dev GRADE GRADE 1657 4.9185275 3.8973856 USBORN USBORN 1682 0.5760999 0.4943218 AGE4 AGE4 1682 79.1159334 5.7347886 MARSTAT4 MARSTAT4 1682 2.5891795 1.5155594 NKIDS4 NKIDS4 1673 4.7866109 3.3231841 HEALTH4 HEALTH4 1682 2.7110583 0.8433434 KHYPER41 KHYPER41 1668 0.5137890 0.4999597 MDIAB41 MDIAB41 1679 0.2858845 0.4519692 NFRAC41 NFRAC41 1680 0.0333333 0.1795589 U43S U43S 1637 0.2700061 0.4440983 TOTMMSE4 TOTMMSE4 1589 20.9351794 7.0774913 CESDTOT4 CESDTOT4 1562 7.7564981 26.2136258 TOTIADL4 TOTIADL4 1672 2.6519139 3.4573068 TOTADL4 TOTADL4 1665 0.9615616 2.0119146 CC43 CC43 1521 1.7343853 0.7410393 EE46 EE46 1529 1.8757358 0.7210330 HHA4 HHA4 1574 0.0349428 0.1836934 OO49LANG OO49LANG 1682 0.1545779 0.3616093 MALE MALE 1682 0.3846611 0.4866598 Table 2 Characteristics of Participants with Deleted Missing Data (N=1,420) Variable GRADE AGE4 NKIDS4 HEALTH4 TOTMMSE4 Label N Mean Std Dev GRADE 1420 5.0147887 3.9178212 AGE4 1420 78.5176056 5.2796737 NKIDS4 1420 HEALTH4 1420 TOTMMSE4 1420 4.7802817 2.6464789 3.3192211 0.8193108 22.0500000 5.5818246 CESDTOT4 TOTIADL4 TOTADL4 CC43 EE46 CESDTOT4 TOTIADL4 TOTADL4 CC43 EE46 1420 7.4521127 27.3298284 1420 2.0971831 2.9983069 1420 0.6521127 1.6047287 1420 1.7204225 0.7337662 1420 1.8732394 0.7188115 Table 3 Regression Model 1 predicting continuous CES-D scores by IADL adjusting for relevant risk factors (N=1420) Parameter Estimates Variable Label Intercept Intercept log_totIADL4 DF Parameter Standard t Value Pr > |t| Estimate Error 1 2.89260 0.59010 4.90 <.0001 1 0.26871 0.03527 7.62 <.0001 AGE4 AGE4 1 -0.00783 0.00633 -1.24 0.2164 USBORN USBORN 1 -0.17585 0.06267 -2.81 0.0051 MARSTAT4 MARSTAT4 1 0.05009 0.02244 2.23 0.0258 1 0.13376 0.03147 4.25 <.0001 1 -0.15154 0.06921 -2.19 0.0287 log_totmmse4 1 -0.39993 0.08180 -4.89 <.0001 log_totadl4 1 0.09470 0.04848 1.95 0.0510 log_grade MALE MALE KHYPER41 KHYPER41 1 0.26904 0.06267 4.29 <.0001 MDIAB41 MDIAB41 1 0.01336 0.07073 0.19 0.8502 NFRAC41 NFRAC41 1 0.00556 0.18771 0.03 0.9764 Table 4 Regression model 2 predicting continuous CES-D scores by religiosity adjusting for relevant risk factors (N=1,420) Variable Label Intercept Intercept 1 2.29349 0.60490 3.79 0.0002 religiosity EE46 1 0.18241 0.04387 4.16 <.0001 AGE4 AGE4 1 0.00076258 0.00633 0.12 0.9042 USBORN USBORN 1 -0.20783 0.06341 -3.28 0.0011 MARSTAT4 MARSTAT4 1 0.05767 0.02273 2.54 0.0113 1 0.11624 0.03193 3.64 0.0003 1 -0.26431 0.07096 -3.72 0.0002 log_totmmse4 1 -0.47590 0.08213 -5.79 <.0001 log_totadl4 1 0.29553 0.04163 7.10 <.0001 log_grade MALE MALE DF Parameter Standard t Value Pr > |t| Estimate Error KHYPER41 KHYPER41 1 0.28213 0.06355 4.44 <.0001 MDIAB41 MDIAB41 1 0.06793 0.07124 0.95 0.3405 NFRAC41 NFRAC41 1 0.08553 0.19028 0.45 0.6531 Table 5 Regression model 3 predicting continuous CES-D scores by IADL and religiosity adjusting for related risk factors (N=1420) ri Parameter Estimates Variable Label Intercept Intercept log_totiIADL4 DF Parameter Standard t Value Pr > |t| Estimate Error 1 2.49831 0.59321 4.21 <.0001 1 0.27136 0.03505 7.74 <.0001 religiosity EE46 1 0.18816 0.04299 4.38 <.0001 AGE4 AGE4 1 -0.00746 0.00630 -1.19 0.2361 USBORN USBORN 1 -0.17567 0.06227 -2.82 0.0048 MARSTAT4 MARSTAT4 1 0.04926 0.02229 2.21 0.0273 1 0.12630 0.03131 4.03 <.0001 1 -0.20680 0.06992 -2.96 0.0032 log_totmmse4 1 -0.38120 0.08139 -4.68 <.0001 log_totadl4 1 0.09704 0.04818 2.01 0.0442 log_grade MALE MALE KHYPER41 KHYPER41 1 0.25241 0.06238 4.05 <.0001 MDIAB41 MDIAB41 1 -0.00136 0.07036 -0.02 0.9845 NFRAC41 NFRAC41 1 0.02663 0.18657 0.14 0.8865 Table 6 Regression Model 4 parameter estimates of CES-D scores as a function of MMSE, religiosity and their interaction Parameter Estimates Variable Label Intercept Intercept DF Parameter Standard t Value Pr > |t| Estimate Error 1 1.89882 0.68741 2.76 0.0058 1 -0.37428 0.21943 -1.71 0.0883 1 0.17825 0.32223 0.55 0.5802 MMSE*religiosity 1 0.00353 0.10395 0.03 0.9729 log_totiadl4 1 0.26517 0.03436 7.72 <.0001 log_totmmse4 religiosity EE46 USBORN USBORN 1 -0.17274 0.06226 -2.77 0.0056 MARSTAT4 MARSTAT4 1 0.04416 0.02189 2.02 0.0438 1 0.12854 0.03120 4.12 <.0001 1 -0.21271 0.06975 -3.05 0.0023 1 0.09444 0.04796 1.97 0.0491 1 0.25742 0.06147 4.19 <.0001 log_grade MALE MALE log_totadl4 KHYPER41 KHYPER41 Table 7 Summary of Stepwise Selection: Final Model 5. Multiple Regression Parameter Estimates of log_CES-D as a Function of the Included Predictors (N=1,420) Step Variable Entered Variable Label Removed Number Partial Model C(p) F Value Pr > F Vars In R-Square R-Square 1 0.1118 0.1118 96.0271 178.52 <.0001 2 0.0133 0.1252 75.3278 21.60 <.0001 1 log_totiadl4 2 KHYPER41 3 log_totmmse4 3 0.0117 0.1369 57.3781 19.22 <.0001 4 log_grade 4 0.0093 0.1462 43.5287 15.43 <.0001 5 EE46 EE46 5 0.0082 0.1543 31.6255 13.66 0.0002 6 MALE MALE 6 0.0085 0.1629 19.0905 14.41 0.0002 7 USBORN USBORN 7 0.0042 0.1671 13.9193 7.14 0.0076 8 MARSTAT4 MARSTAT4 8 0.0024 0.1695 11.8829 4.03 0.0449 9 log_totadl4 9 0.0023 0.1718 10.0000 3.88 0.0490 KHYPER41 Table 8 Partial Regressor Residuals as a Diagnostic Tool to Check Linearity (Functional Form) Partial Regression Residual Plot Table 8 Partial Regressor Residuals as a Diagnostic Tool to Check Linearity (Functional Form) Table 9 Final Multiple Regression Model with 95% Confidence Intervals Reported Variable Label Intercept Intercept log_totiadl4 DF Parameter Standard t Estimate Error Value Pr > |t| 95% Confidence Limits 1 1.87747 0.27832 6.75 <.0001 1.33151 2.42344 1 0.26522 0.03431 7.73 <.0001 0.19791 0.33252 EE46 EE46 1 0.18910 0.04289 4.41 <.0001 0.10496 0.27324 USBORN USBORN 1 -0.17286 0.06213 -2.78 0.0055 -0.29474 -0.0509 MARSTAT4 MARSTAT4 1 0.04418 0.02187 2.02 0.0436 0.00127 0.08708 1 0.12851 0.03117 4.12 <.0001 0.06735 0.18966 1 -0.21264 0.06970 -3.05 0.0023 -0.34936 -0.0759 log_totmmse4 1 -0.36734 0.08038 -4.57 <.0001 -0.52502 -0.2096 log_totadl4 1 0.09436 0.04788 1.97 0.0490 0.0004236 0.18829 1 0.25746 0.06144 4.19 <.0001 log_grade MALE KHYPER41 MALE KHYPER41 0.13695 0.37798 REFERENCES 1.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. JAMA 1997; 278:1186-90. 2. Black SA, Goodwin JS, Markides KS. The association between chronic diseases and depressive symptomatology in older Mex ican Americans. J Gerontol: Series A: Biologic Sci Medic Sci. 1998;53A:M188–M194. 3. Gonzalez HM, Haan MN, Hinton L. Acculturation and the prevalence of depression in older Mexican Americans: baseline results of the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. JAm Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:948–953.ican Americans. J Gerontol: Series A: Biologic Sci Medic Sci. 1998;53A:M188–M194. 4. Schneider MG, Chiriboga DA. Associations of stress and depressive symptoms with cancer in older Mexican Americans. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:698–704. 5. Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Diala C, et al. Social class, assets, organizational control and the prevalence of common groups of psychiatric disorders. Soc Sci Med 1998; 47: 2043-53. 6. Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science 1992; 255: 946-52. 7. Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, Kudkr HS, Krishnan KR, Sibert TE. Religious coping and cognitive symptoms of depression in elderly medical patients. PsycilOsotnacics. 1995;36:369–376. 8. Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Ormel J, et al. Psychological status among elderly people with chronic diseases: does type of disease play a part? J Psychosom Res. 1996; 40: 521–534. 9. Peruzza S, Sergi G, Vianello A, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in elderly subjects: impact on functional status and quality of life. Respir Med. 2003;97:612–617. 10. Rao A, Cohen HJ. Symptom management in the elderly cancer patient: fatigue, pain, and depression. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:150–157. 11. Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Skidmore ER, et al. Onset of depression in elderly persons after hip fracture: Implications for prevention and early intervention of late-life depression. JAm Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:81–86. 12. Reyes-Ortiz CA, Berges IM, Mukaila AR, et al. Church attendance mediates the association between depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008 May; 63(5): 480-86.