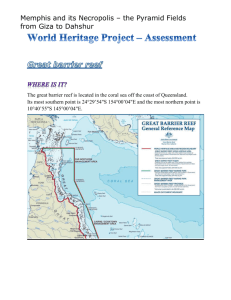

biodiversity of the great barrier reef

advertisement