Lecture One - Noppa

advertisement

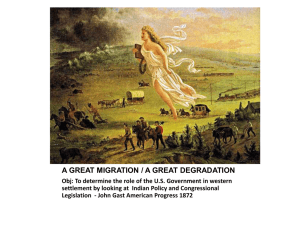

Lecture 1 Outline Indian and Environment; an Ecological History from Pre-contact to Present Traditional Historiography—Columbus discovered a virgin continent, sparsely populated by Indians with protocivilization, i.e. savages. Revisionist Historians—Populated, civilized world, destroyed by newcomers (violence, disease, etc.) Laden with tones of Euro-American self-indictment. Indian became a mythical, noble savage that lived in peace and balance with nature, vanishing in the wake of negative progress. Arrival and the Pleistocene Extinctions—Estimations of human arrival vary. 80,000–23,000 BC possible, 23,000– 10,000 most probable. Glaciology traditionally sets date at 11,000 BC; archeology evidence still inconclusive. Mass extinctions dated to 11k–10k BC. Climate change or hunting? Human hand likely as earlier ice age cycles did not produce similar extinctions. Trophic cascade theory popular at present. The Pleistocene extinctions a highly politically charged issue. European Arrival—Europeans described pristine, “virgin” land, but also, somewhat paradoxically, a “peopled land”. Pre-Columbian population estimates vary greatly, typically ½–50 million – also politically charged. Eden was a European construct, an outsider’s view, a modern construct. “The acceleration of environmental transformation blinds us to their antiquity” – David Lowenthal. Modern “widowed” land interpretation has gained credence and acceptance. The Landscape upon Contact—Native-altered landscapes in historical and ecological record. Many landscapes viewed by Europeans as “natural” actually highly anthropogenic and/or pyrogenic. Indians understood the link between timely burns and biodiversity but also abused land: “[the Indian], his country is large.” Destructive aspects overshadowed by noble savage interpretations. Indian fires and land-use practices became akin to forces of nature: not anthropogenic but “natural”. The Prairie Ecosystem and the Buffalo—Noble savage tradition places blame solely on whites. Estimated buffalo population at Columbus’ arrival ranges from 30–100 million – often called the greatest common resource in North America. Indian utilization efficient or wasteful? Buffalo jumps and communal hunting invite perspective fallacies. In the 1800s non-native market pressure hastened demise, but native pressure, horses and guns, a factor as well. All parties eager to trade – traditional view sees Indian hunters forced to turn into commercial (wasteful) hunters via demand for buffalo robes and meat. Native ideals about nature and reincarnation/religion may partially explain native over-exploitation. White hunters came later, but at a decisive moment. The era of the great buffalo hunts over by 1870s – reckoning begins in earnest. Deer in the Southern Woodlands—“Deerskins for trifles” traditional interpretation, corruption by alcohol also a popular take. Both interpretations laden with tones of “simple Indian” stereotype – a racist construct. Marxist interpretation sees European market forces working to enslave Indians. Modern interpretations see Indians as savvy, rational role players, found niches and persevered. Sustained contact after 1600 brought markets as well as diseases, but also opportunity amid reorganization (the “middlemen theory”). Natives understood advantages of Europeans technology and adapted fittingly. Elementary conundrum of Ecological Indian: Deer were sacred to Indians but nonetheless were nearly hunted to extinction by them, why? Pre-contact protoeconomy for deerskins (as tribute) exacerbated by new markets, alcohol also played role. Withering stocks leads to competition, impact on relations amongst tribes – excessive feuding over hunting lands, whites infringed on Indian lands/privileges, exacerbating situation. Native cosmology also a factor (reincarnation/religion): “The more we kill, the more we will prosper”. Around 1800 deer nearly extinct in SE, then markets abruptly change. Indians of South seek out other roles to meet their economic needs. Conservation—paradoxically, likely a European-inspired notion amongst Indians. The roles traditionally associated with Indians as native natural conservationists are 20th-century concepts that are largely absent from historical record. Indians quickly exploited perception that they were authorized to decide on natural resource issues. Conservation, in effect, became a part of Indian culture and religious views on heels of game decimation. Taboos changed, creative synthesis emerged. End Result—Noble, conservation-minded savage ideal lacks historical validity, but has positive aspects otherwise: Indians gained a voice in resource issues in the 20th century as a result. Undeniable indigenous knowledge about nature has found respect amongst biologists, conservationists etc., as well as those who support what Callicott called the “land ethic”. Native cosmologies have also been viewed as complement to Western empirical scientific one. Negative aspects of this ideal is that it forces Indian into stereotyped role. “Native peoples are supposed to be keepers of the earth, not protectors of its poison.” A difficult position when Indians have differing opinions about resource use. Noble savage imagery has its deeper roots in European selfcriticism and attendant feelings of guilt – the myth oftentimes obscures that Indians are not an exceptional type of human being. Selected Reading: “Skull Valley Goshutes and the Politics of Nuclear Waste”, David R. Lewis, in Native Americans and the Environment (2007), Michael E. Harkin and David R. Lewis (eds) AvP13 Andrew Pattison Oulu University Focus Areas in North American History 682373A