BSR & BHPR Guidelines for the Management of adults with ANCA

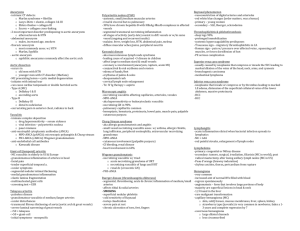

advertisement