Historians on Nasser - ib world history Y2

advertisement

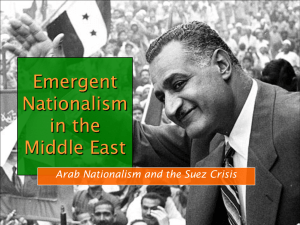

Historians on Nasser Robert Stephens Nasser (1971) Although afraid of creating a military dictatorship, Nasser and the Free Officers banned opposition parties, student groups, and trade unions, in hopes of creating a mass movement of the people behind the Liberation Rally – but Nasser was dismayed to find the masses did not follow the army’s charge, but hung back as on-lookers. Anthony Nutting from Nasser (1972) 1 But at the outset, Nasser’s aims and ambitions were strictly limited to the eviction of the British. Far from being directed against the throne, his initial object was, so he subsequently told me, to try and put some stuffing into the king and by creating a military opposition to British imperialism within the army, to strength Farouk’s resistance to further encroachments on Egypt’s sovereignty. Neither Nasser nor his conspirators had any love for the king or his palace clique. Peter Mansfield, A History of the Middle East (1991) The years 1956-1959 marked the high tide of Nasserism as he seemed to sweep all before him. His appeal to the Arabs – especially the younger generation, who formed the majority – was overwhelming. They saw him as a modern Saladin who would unite them in order to drive out the Zionists, the crusaders of the 20th century. The danger for Nasser was that he was rising expectations which neither he nor Egypt could fulfill. Said Aburish, Nasser: The Last Arab (2004) There is no escaping the conclusion that Nasser represented an odd type of dictator. He manifested a need to be loved. . . which most other dictators do not have. His dictatorship was a mixture of populism and a need to be accepted as a man of principle. Anne Alexander’s Nasser (2005) By the 1952 coup, Nasser’s claim that parliament democracy would return seemed highly unlikely and Nasser himself claimed “in a year and half we have been able to wipe out corruption. If the right to vote were restored, the same landowners would be elected – the feudal interest. We don’t want the capitalists and the wealthy back in power. If we open the government to them now, the revolution might just as well be forgotten . . .” Despite widespread poverty and illiteracy, Egyptian agriculture was actually highly capitalized, mechanized and well integrated into the world economy. But the Officers’ campaign struck a social and emotional chord with millions. Martin Meredith, The State of Africa (2006) Yet whatever disasters befell Egypt, Nasser never lost his popularity with the masses. When after the 1967 defeat , he announced his resignation, popular protests propelled him back into office. His reputation as the man who stripped the old ruling class of their power, nationalized their wealth, booted out foreigners, restored to Egypt a sense of dignity and self-respect and led the country towards national regeneration – all of this counted for far more than the setbacks. Eric Hobsbawm in Revolutionaries (2007) Although illegal in the use of force, the military takeover was a genuinely innovating military regime of the type that appear where the necessity of social revolution is evident, where several of the objective conditions of it are present, but also where the social bases or institutions of civilian life are too feeble to carry it out. The armed forces, being in some cases, the only available force with the capacity to take and carry out decisions, may have to take the place of civilian forces, even to the point of turning their officers into administrators. 1 Nutting had served as under-secretary to PM Eden and negotiated the British withdrawal from Suez In 1956