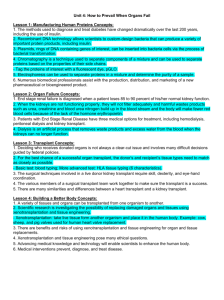

Specifically, debate over organ sales is necessary given shortages

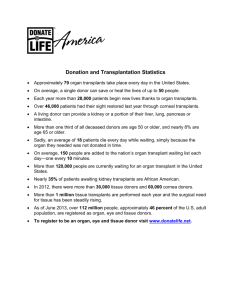

advertisement