8 Things You May Not Know About the Louisiana Purchase

advertisement

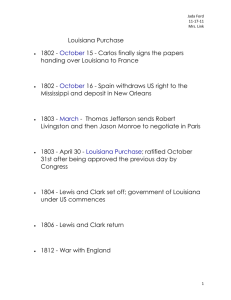

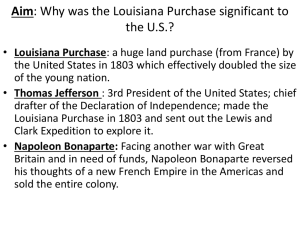

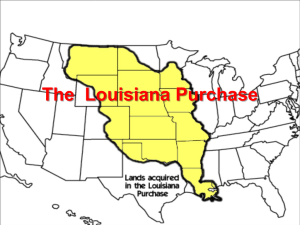

8 Things You May Not Know About the Louisiana Purchase By Jesse Greenspan April 30, 2013 On April 30, 1803, U.S. representatives in Paris agreed to pay $15 million for about 828,000 square miles of land that stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada. This deal, known as the Louisiana Purchase, nearly doubled the size of the United States. President Thomas Jefferson called it “an ample provision for our posterity and a widespread field for the blessings of freedom.” Yet it also had detractors on both the French and American sides. Two hundred ten years later, explore eight facts about the wars, negotiating tactics and lucky coincidences that made the Louisiana Purchase possible. 1. France had just re-taken control of the Louisiana Territory. French explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle first claimed the Louisiana Territory, which he named for King Louis XIV, during a 1682 canoe expedition down the Mississippi River. France ceded the land to Spain 80 years later—and lost most of its other North American holdings to Great Britain—following its defeat in the French and Indian War. In 1800, however, French leader Napoleon Bonaparte pressured Spain to sign the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso, under which he received the Louisiana Territory and six warships in exchange for placing the Spanish king’s son-in-law on the throne of the newly created kingdom of Etruria in northern Italy. When word of the secret agreement leaked out, President Jefferson became extremely worried. French-controlled Louisiana would become “a point of eternal friction with us,” he wrote in April 1802, and would force us to “marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.” 2. The United States nearly went to war over Louisiana. Under a 1795 treaty with Spain, U.S. merchants and farmers could send their goods down the Mississippi River and store them in New Orleans without paying export duties. For many Americans, this so-called right of deposit was important enough that talk of war began proliferating when it was revoked in October 1802. Former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, using the pen name Pericles, wrote that the United States should “seize at once on the Floridas and New Orleans and then negotiate.” Meanwhile, the governor of the Mississippi Territory claimed that 600 militiamen would be enough to grab hold of New Orleans, and Federalist Senator James Ross of Pennsylvania advocated taking possession of the city with 50,000 men. Even Jefferson’s own party, the Democratic-Republicans, supported a resolution that would keep 80,000 men ready to march at a moment’s notice. This bravado arose largely because Napoleon’s powerful army had yet to arrive in Louisiana. Several thousand troops slated for the territory were instead being decimated by a slave rebellion and yellow fever in Saint Domingue (now Haiti), and additional troops were stuck in a Dutch port waiting for the winter ice to clear. 3. The United States never asked for all of Louisiana. On the advice of a French friend, Jefferson offered to purchase land from Napoleon rather than threatening war over it. He instructed his two chief negotiators, special envoy James Monroe and minister Robert Livingston, to pay up to $9.375 million for New Orleans and Florida (the later of which remained under Spanish control). If that failed, they were to try to get back the right of deposit. Livingston also floated a plan for the United States to take over the two-thirds of Louisiana located north of the Arkansas River, which he argued would serve as a crucial buffer between French Louisiana and British Canada. But although the Americans never asked for it, Napoleon dangled the entire territory in front of them on April 11, 1803. A treaty, dated April 30 and signed May 2, was then worked out that gave Louisiana to the United States in exchange for $11.25 million, plus the forgiveness of $3.75 million in French debt. 4. Even that low price was too steep for the United States. Napoleon wanted the money immediately in order to prepare for war with Great Britain. But despite landing Louisiana for less than three cents an acre, the price was more than the United States could afford. As a result, it was forced to borrow from two European banks at 6 percent interest. It did not finish repaying the loan until 1823, by which time the total cost for the Louisiana Purchase had risen to over $23 million. 5. The Louisiana negotiations helped put James Monroe in the proverbial poor house. After spending three years as governor of Virginia, Monroe purportedly hoped to retire from politics and make some money opening a law practice and developing his landholdings. Barely a month went by, however, before Jefferson nominated him as a special envoy to help Livingston with the Louisiana Purchase negotiations. “Were you to refuse to go, no other man could be found who does this,” Jefferson wrote to him in January 1803, adding that “all eyes, all hopes, are now fixed on you.” In order to raise money for the passage to France, a cash-strapped Monroe sold off his silver flatware, porcelain plates and a white-and-gold china tea set. The future president, who served from 1817 to 1825, remained in debt for the rest of his life, even after receiving a $30,000 congressional appropriation for “public losses and sacrifices.” 6. Napoleon’s brothers tried to talk him out of it. A few days before Monroe arrived in Paris, Napoleon’s brothers, Joseph and Lucien, found out about his plans to sell off Louisiana. According to Lucien’s memoirs, the two of them visited Napoleon at Tuileries Palace, where they found him bathing in rose-scented water. When Joseph intimated that he would lead the opposition to the deal, Napoleon accused him of being “insolent.” He then purposely soaked his brothers by falling backwards in the tub. The argument allegedly continued after Joseph went home to change. Lucien declared that “if I were not your brother I would be your enemy,” and Napoleon responded by smashing a snuffbox on the floor. 7. Many Americans likewise opposed the Louisiana Purchase. Members of the Federalist Party, already a significant minority in both houses of Congress, worried that the Louisiana Purchase would further reduce their clout. In summing up the feelings of his cohorts, former congressman Fisher Ames wrote, “We are to give money of which we have too little for land of which we already have too much.” Only one Federalist senator supported ratification of the Louisiana Purchase treaty, which passed by a 24-7 vote. Jefferson himself had doubts about the legality of the Louisiana Purchase, saying he had “stretched the Constitution until it cracked.” 8. The treaty did not state specific boundaries. When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark departed from St. Louis in May 1804 to explore the northern portion of Louisiana, the exact boundaries of the newly acquired territory had yet to be hashed out. Based on an analysis of old French maps, the United States claimed West Florida, an area along the Gulf Coast in present-day Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Spain disputed this until 1819, when the Adams-Onís Treaty gave the United States all of Florida in exchange for surrendering its claim to Texas. In the north, Great Britain and the United States agreed in 1818 to establish the 49th parallel as the border between them from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains.